Proposed Outline for Plain Talk Teaching Case

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

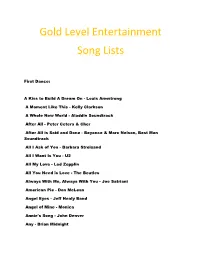

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists

Gold Level Entertainment Song Lists First Dance: A Kiss to Build A Dream On - Louis Armstrong A Moment Like This - Kelly Clarkson A Whole New World - Aladdin Soundtrack After All - Peter Cetera & Cher After All is Said and Done - Beyonce & Marc Nelson, Best Man Soundtrack All I Ask of You - Barbara Streisand All I Want Is You - U2 All My Love - Led Zepplin All You Need is Love - The Beatles Always With Me, Always With You - Joe Satriani American Pie - Don McLean Angel Eyes - Jeff Healy Band Angel of Mine - Monica Annie's Song - John Denver Any - Brian Midnight As Long as I'm Rocking With You - John Conlee At Last - Celine Dion At Last - Etta James At My Most Beautiful - R.E.M. At Your Best - Aaliyah Battle Hymn of Love - Kathy Mattea Beautiful - Gordon Lightfoot Beautiful As U - All 4 One Beautiful Day - U2 Because I Love You - Stevie B Because You Loved me - Celine Dion Believe - Lenny Kravitz Best Day - George Strait Best In Me - Blue Better Days Ahead - Norman Brown Bitter Sweet Symphony - Verve Blackbird - The Beatles Breathe - Faith Hill Brown Eyes - Destiny's Child But I Do Love You - Leann Rimes Butterfly Kisses - Bob Carlisle By My Side - Ben Harper By Your Side - Sade Can You Feel the Love - Elton John Can't Get Enough of Your Love, Babe - Barry White Can't Help Falling in Love - Elvis Presley Can't Stop Loving You - Phil Collins Can't Take My Eyes Off of You - Frankie Valli Chapel of Love - Dixie Cups China Roses - Enya Close Your Eyes Forever - Ozzy Osbourne & Lita Ford Closer - Better than Ezra Color My World - Chicago Colour -

All Audio Songs by Artist

ALL AUDIO SONGS BY ARTIST ARTIST TRACK NAME 1814 INSOMNIA 1814 MORNING STAR 1814 MY DEAR FRIEND 1814 LET JAH FIRE BURN 1814 4 UNUNINI 1814 JAH RYDEM 1814 GET UP 1814 LET MY PEOPLE GO 1814 JAH RASTAFARI 1814 WHAKAHONOHONO 1814 SHACKLED 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE 20 FINGERS SHORT SHORT MAN 28 DAYS RIP IT UP 3 DOORS DOWN KRYPTONITE 3 DOORS DOWN HERE WITHOUT YOU 3 JAYS IN MY EYES 3 JAYS FEELING IT TOO 3 THE HARDWAY ITS ON 360 FT GOSSLING BOYS LIKE YOU 360 FT JOSH PYKE THROW IT AWAY 3OH!3 STARSTRUKK ALBUM VERSION 3OH!3 DOUBLE VISION 3OH!3 DONT TRUST ME 3OH!3 AND KESHA MY FIRST KISS 4 NON BLONDES OLD MR HEFFER 4 NON BLONDES TRAIN 4 NON BLONDES PLEASANTLY BLUE 4 NON BLONDES NO PLACE LIKE HOME 4 NON BLONDES DRIFTING 4 NON BLONDES CALLING ALL THE PEOPLE 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP 4 NON BLONDES SUPERFLY 4 NON BLONDES SPACEMAN 4 NON BLONDES MORPHINE AND CHOCOLATE 4 NON BLONDES DEAR MR PRESIDENT 48 MAY NERVOUS WRECK 48 MAY LEATHER AND TATTOOS 48 MAY INTO THE SUN 48 MAY BIGSHOCK 48 MAY HOME BY 2 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER GOOD GIRLS 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER EVERYTHING I DIDNT SAY 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER DONT STOP 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER AMNESIA 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER SHE LOOKS SO PERFECT 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER KISS ME KISS ME 50 CENT CANDY SHOP 50 CENT WINDOW SHOPPER 50 CENT IN DA CLUB 50 CENT JUST A LIL BIT 50 CENT 21 QUESTIONS 50 CENT AND JUSTIN TIMBERLAKE AYO TECHNOLOGY 6400 CREW HUSTLERS REVENGE 98 DEGREES GIVE ME JUST ONE NIGHT A GREAT BIG WORLD FT CHRISTINA AGUILERA SAY SOMETHING A HA THE ALWAYS SHINES ON TV A HA THE LIVING DAYLIGHTS A LIGHTER SHADE OF BROWN ON A SUNDAY AFTERNOON -

100 Years: a Century of Song 1990S

100 Years: A Century of Song 1990s Page 174 | 100 Years: A Century of song 1990 A Little Time Fantasy I Can’t Stand It The Beautiful South Black Box Twenty4Seven featuring Captain Hollywood All I Wanna Do is Fascinating Rhythm Make Love To You Bass-O-Matic I Don’t Know Anybody Else Heart Black Box Fog On The Tyne (Revisited) All Together Now Gazza & Lindisfarne I Still Haven’t Found The Farm What I’m Looking For Four Bacharach The Chimes Better The Devil And David Songs (EP) You Know Deacon Blue I Wish It Would Rain Down Kylie Minogue Phil Collins Get A Life Birdhouse In Your Soul Soul II Soul I’ll Be Loving You (Forever) They Might Be Giants New Kids On The Block Get Up (Before Black Velvet The Night Is Over) I’ll Be Your Baby Tonight Alannah Myles Technotronic featuring Robert Palmer & UB40 Ya Kid K Blue Savannah I’m Free Erasure Ghetto Heaven Soup Dragons The Family Stand featuring Junior Reid Blue Velvet Bobby Vinton Got To Get I’m Your Baby Tonight Rob ‘N’ Raz featuring Leila K Whitney Houston Close To You Maxi Priest Got To Have Your Love I’ve Been Thinking Mantronix featuring About You Could Have Told You So Wondress Londonbeat Halo James Groove Is In The Heart / Ice Ice Baby Cover Girl What Is Love Vanilla Ice New Kids On The Block Deee-Lite Infinity (1990’s Time Dirty Cash Groovy Train For The Guru) The Adventures Of Stevie V The Farm Guru Josh Do They Know Hangin’ Tough It Must Have Been Love It’s Christmas? New Kids On The Block Roxette Band Aid II Hanky Panky Itsy Bitsy Teeny Doin’ The Do Madonna Weeny Yellow Polka Betty Boo -

ARTIST SONG 112 Cupid 112 Peaches and Cream a Taste of Honey Boogie Oogie, Oogie Aaliyah at Your Best Abba Dancing Queen After 7 Can't Stop Ah Ha Take on Me Al B

ARTIST SONG 112 Cupid 112 Peaches And cream A Taste Of Honey Boogie Oogie, Oogie Aaliyah At Your Best Abba Dancing Queen After 7 Can't Stop Ah Ha Take On Me Al B. Sure Nite And Day Al Green Here I Am (Come And Take Me) Al Green How Can You Mend A Broken Heart Al Green I'm Still In Love With You Al Green Let's Stay Together Al Green Tired Of Being Alone Al Jarreau After All Al Jarreau Morning Al Jarreau Were In This Love Together Al Wilson Show And Tell Alabama Mountain Music Alan Jackson Chattahoochie Alicia Bridges I Love The Night Life All-4-One I Swear Arrested Development Mr.Wendal Average White Band Cut The Cake B.J. Thomas Raindrops Keep Fallin On My Head B.J. Thomas Wont You Play Another Somebody….. Babyface Everytime I Close My Eyes Babyface For The Cool In You Babyface Never Keeping Secrets Babyface When Can I See You Babyface Whip Appeal Bachman-Turner Overdrive Takin Care Of Business Bachman-Turner Overdrive You A'int Seen Nothin Yet Backstreet Boys Everybody (Backstreets Back) Backstreet Boys Larger Than Life Barbra Streisand The Way We Were Bar-Kays, The Shake You Rump To The Funk Barry Manilow Copacabana Barry Manilow I Write The Songs Barry White Ectasy, When You Lay Next to Me Barry White Practice What You Preach Barry White Your The First, The Last, My Everything Beach Boys, The Surfin' USA Beatles, The A Day In The Life Beatles, The Come Togeter Beatles, The Do You Want to Know A Secret Beatles, The Eight Days a Week Beatles, The Nowhere Man Beatles, The The Long And Winding Road Beatles, The Twist And Shout Bee Gees, The How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees, The How Deep Is Your Love Bee Gees, The Jive Talkin' Bee Gees, The Night Fever Bee Gees, The Stayin Alive Bee Gees, The Too Much Heaven Bee Gees, The Tragety Bee Gees, The You Should Be Dancin Bell Biv DeVoe Do Me Ben E. -

Songs by Artist

Songs by Artist Title Title (Hed) Planet Earth 2 Live Crew Bartender We Want Some Pussy Blackout 2 Pistols Other Side She Got It +44 You Know Me When Your Heart Stops Beating 20 Fingers 10 Years Short Dick Man Beautiful 21 Demands Through The Iris Give Me A Minute Wasteland 3 Doors Down 10,000 Maniacs Away From The Sun Because The Night Be Like That Candy Everybody Wants Behind Those Eyes More Than This Better Life, The These Are The Days Citizen Soldier Trouble Me Duck & Run 100 Proof Aged In Soul Every Time You Go Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 10CC Here Without You I'm Not In Love It's Not My Time Things We Do For Love, The Kryptonite 112 Landing In London Come See Me Let Me Be Myself Cupid Let Me Go Dance With Me Live For Today Hot & Wet Loser It's Over Now Road I'm On, The Na Na Na So I Need You Peaches & Cream Train Right Here For You When I'm Gone U Already Know When You're Young 12 Gauge 3 Of Hearts Dunkie Butt Arizona Rain 12 Stones Love Is Enough Far Away 30 Seconds To Mars Way I Fell, The Closer To The Edge We Are One Kill, The 1910 Fruitgum Co. Kings And Queens 1, 2, 3 Red Light This Is War Simon Says Up In The Air (Explicit) 2 Chainz Yesterday Birthday Song (Explicit) 311 I'm Different (Explicit) All Mixed Up Spend It Amber 2 Live Crew Beyond The Grey Sky Doo Wah Diddy Creatures (For A While) Me So Horny Don't Tread On Me Song List Generator® Printed 5/12/2021 Page 1 of 334 Licensed to Chris Avis Songs by Artist Title Title 311 4Him First Straw Sacred Hideaway Hey You Where There Is Faith I'll Be Here Awhile Who You Are Love Song 5 Stairsteps, The You Wouldn't Believe O-O-H Child 38 Special 50 Cent Back Where You Belong 21 Questions Caught Up In You Baby By Me Hold On Loosely Best Friend If I'd Been The One Candy Shop Rockin' Into The Night Disco Inferno Second Chance Hustler's Ambition Teacher, Teacher If I Can't Wild-Eyed Southern Boys In Da Club 3LW Just A Lil' Bit I Do (Wanna Get Close To You) Outlaw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) Outta Control Playas Gon' Play Outta Control (Remix Version) 3OH!3 P.I.M.P. -

CMB Complaint

Case 1:19-cv-02703-RLY-DML Document 1 Filed 07/01/19 Page 1 of 28 PageID #: 1 AMMEEN VALENZUELA ASSOCIATES LLP 750 Banister Building 155 E. Market St. Indianapolis, IN 46204-3253 Telephone: 1.317.423.7 505 Facsimile: 1.800.613.4707 [email protected] James J. Ammeen, Jr., No. 18519-49 -and- REITLER KAILAS & ROSENBLATT LLC 885 Third Avenue, 20th Floor New York, New York 10022 Telephone: | .212.209.3050 Facsimile: 1.212.37 1.5500 b caplan@re itlerl aw. c om Brian D. Caplan, pro hac vice øpplication to be submitted Attorneysfor Pløintffi CMB Entertainment, LLC UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA ------x CMB ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, and BRYAN ABRAMS, : derivatively on behalf of CMB ENTERTAINMENT, LLC, : Case No. l:19-cv-2703 Plaintiffs, COMPLAINT AND JURY DEMAND -against- MARK CALDERON and PYRAMID ENTERTAINMENT GROUP,INC., Defendants. Plaintiffs CMB Entertainment, LLC ("CMB") and Bryan Abrams ("Abrams"), derivatively on behalf of CMB (collectively, "Plaintiffs"), by their undersigned counsel, as and for their Complaint against Defendants Mark Calderon ("Calderon") and Pyramid Entertainment Group, Inc. ("Pyramid" and collectively with Calderon, "Defendants") hereby allege as follows: Case 1:19-cv-02703-RLY-DML Document 1 Filed 07/01/19 Page 2 of 28 PageID #: 2 NATURE OF ACTION 1. CMB, a limited liability company whose members are two of the founding members of the well-known R&B group popularly known as "Color Me Badd" (the "Group"), it the owner of the federally registered trademark "COLOR ME BADD" associated with the Group (the "Mark"). 2. Plaintiff Abrams is one of the two members of CMB and brings this action on behalf of CMB to redress Defendants' willful infüngement of the Mark in violation of Section 43 of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. -

Sample Song List 032419

Song Name Artist Category (If You're Wondering If I Want You To) I Want You To Weezer 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 1, 2, 3, 4 Plain White T's 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 1,2 Step Ciara f/Missy ELLiott 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 7 Things MiLey Cyrus 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock 867-5309 / Jenny Tommy Tutone 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Love That WiLL Last Renee OLstead 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Moment Like This KeLLy CLarkson 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Sky FuLL of Stars CoLdpLay 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock A Thousand MiLes Vanessa CarLton 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Alejandro Lady GaGa f/ Redone 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock AlL About That Bass Meghan Trainor 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock AlL Summer Long (Summertime) Kid Rock 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock American Boy (Radio Edit w/ Kanye) EsteLLe 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Anaconda Nicki Minaj 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Apache (Jump On It) The SugarhiLL Gang 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock ApoLogize TimbaLand f/ One RepubLic 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Are You Gonna Go My Way Lenny Kravitz 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock At Last Beyoncé 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Baby Got Back (Big Butt Song) Sir Mix-a-Lot 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bad Boy for Life P. Diddy, BLack Rob & Mark Curry 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bad Romance Lady Gaga 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Bang Bang Jessie J, Ariana Grande & Nicki Minaj 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beat It FaLL Out Boy f/ John Mayer 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Because You Live Jesse McCartney 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beep Pussycat DoLLs, The 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Beer ReeL Big Fish 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Berzerk Eminem 00's Hip Hop, Pop, Rock Best Friend (feat. -

Color Me Badd C.M.B

Color Me Badd C.M.B. mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Hip hop Album: C.M.B. Country: Canada Released: 1991 Style: RnB/Swing MP3 version RAR size: 1761 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1603 mb WMA version RAR size: 1572 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 502 Other Formats: AA AU AUD DMF ASF MOD WAV Tracklist Hide Credits I Wanna Sex You Up 1 4:07 Mixed By – Howie Tee 2 All 4 Love 3:31 3 Heartbreaker 3:59 4 I Adore Mi Amor 4:51 5 Groove My Mind 5:09 I Wanna Sex You Up (Reprise) 6 1:09 Mixed By – Howie Tee Roll The Dice 7 4:48 Mixed By – Bobby BrooksProducer – Nick Mundy 8 Slow Motion 4:25 Thinkin' Back 9 5:21 Mixed By – James Pollock 10 I Adore Mi Amor (Interlude) 0:48 Color Me Badd 11 4:05 Mixed By – Spyderman, Warren Woods 12 Your Da One I Onena Love 4:10 Credits Producer – Dr. Freeze (tracks: 1, 6, 11), Hamza Lee (tracks: 4, 9, 10), Howie Tee (tracks: 2, 3, 8, 12), Royal Bayyan (tracks: 4, 5, 9, 10) Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year Color Me C.M.B. (CD, 7599-24429-2 Giant Records 7599-24429-2 Europe 1991 Badd Album) Color Me 024429 C.M.B. (LP) Giant Records 024429 Colombia 1991 Badd Color Me C.M.B. (CD, WPCP-4413 Giant Records WPCP-4413 Japan 1991 Badd Album) Color Me C.M.B. (Cass, 9 24429-4 Giant Records 9 24429-4 US 1991 Badd Album, SR) Giant Records, 4-24429, W4 Color Me C.M.B. -

Analysis of Grammatical Errors in Pop Song Lyrics

University of South Bohemia in České Budějovice Faculty of Education Department of English Studies Bachelor thesis Analysis of grammatical errors in pop song lyrics Magdalena Smolková Supervisor: Mgr. Ludmila Zemková Ph.D. České Budějovice 2018 Prohlášení Prohlašuji, že jsem svoji bakalářskou práci na téma „Analýza gramatických chyb v textech popových písní“ vypracovala samostatně pouze s použitím pramenů a literatury uvedených v seznamu citované literatury. Prohlašuji, že v souladu s § 47b zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. v platném znění souhlasím se zveřejněním své bakalářské práce, a to v nezkrácené podobě fakultou elektronickou cestou ve veřejně přístupné části databáze STAG provozované Jihočeskou univerzitou v Českých Budějovicích na jejích internetových stránkách, a to se zachováním mého autorského práva k odevzdanému textu této kvalifikační práce. Souhlasím dále s tím, aby toutéž elektronickou cestou byly v souladu s uvedeným ustanovením zákona č. 111/1998 Sb. zveřejněny posudky školitele a oponentů práce i záznam o průběhu a výsledku obhajoby kvalifikační práce. Rovněž souhlasím s porovnáním textu mé kvalifikační práce s databází kvalifikačních prací Theses.cz provozovanou Národním registrem vysokoškolských kvalifikačních prací a systémem na odhalování plagiátů. V Českých Budějovicích dne 23.4.2018 …..………………………… Magdalena Smolková Poděkování Ráda bych poděkovala Mgr. Ludmile Zemkové, Ph.D. za vedení, podporu a rady při psaní mé bakalářské práce. Rovněž bych ráda poděkovala Mgr. Jiřímu Kloudovi za korekturu této práce. Acknowledgements I would like to thank my supervisor Mgr. Ludmila Zemková, Ph.D. for her guidance, great support and kind advice throughout writing my bachelor thesis. Also, I would like to thank Mgr. Jiří Klouda for correction of this thesis. Anotace Práce bude zkoumat výskyt gramatických chyb v textech písní, řadících se do hudebního žánru pop-music. -

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List

Party Warehouse Karaoke & Jukebox Song List Please note that this is a sample song list from one Karaoke & Jukebox Machine which may vary from the one you hire You can view a sample song list for digital jukebox (which comes with the karaoke machine) below. Song# ARTIST TRACK NAME 1 10CC IM NOT IN LOVE Karaoke 2 10CC DREADLOCK HOLIDAY Karaoke 3 2 PAC CALIFORNIA LOVE Karaoke 4 4 NON BLONDES WHATS UP Karaoke 5 50 CENT IN DA CLUB Karaoke 6 A HA TAKE ON ME Karaoke 7 A HA THE SUN ALWAYS SHINES ON TV Karaoke 8 A1 CAUGHT IN THE MIDDLE Karaoke 9 AALIYAH I DONT WANNA Karaoke 10 ABBA DANCING QUEEN Karaoke 11 ABBA WATERLOO Karaoke 12 ABBA THANK YOU FOR THE MUSIC Karaoke 13 ABBA SUPER TROUPER Karaoke 14 ABBA SOS Karaoke 15 ABBA ROCK ME Karaoke 16 ABBA MONEY MONEY MONEY Karaoke 17 ABBA MAMMA MIA Karaoke 18 ABBA KNOWING ME KNOWING YOU Karaoke 19 ABBA FERNANDO Karaoke 20 ABBA CHIQUITITA Karaoke 21 ABBA I DO I DO I DO I DO I DO Karaoke 22 ABC POISON ARROW Karaoke 23 ABC THE LOOK OF LOVE Karaoke 24 ACDC STIFF UPPER LIP Karaoke 25 ACE OF BASE ALL THAT SHE WANTS Karaoke 26 ACE OF BASE DONT TURN AROUND Karaoke 27 ACE OF BASE THE SIGN Karaoke 28 ADAM ANT ANT MUSIC Karaoke 29 AEROSMITH CRAZY Karaoke 30 AEROSMITH I DONT WANT TO MISS A THING Karaoke 31 AEROSMITH LOVE IN AN ELEVATOR Karaoke 32 AFROMAN BECAUSE I GOT HIGH Karaoke 33 AIR SUPPLY ALL OUT OF LOVE Karaoke 34 ALANIS MORISSETTE YOU OUGHTA KNOW Karaoke 35 ALANIS MORISSETTE THANK U Karaoke 36 ALANIS MORISSETTE ALL I REALLY WANT Karaoke 37 ALANIS MORISSETTE IRONIC Karaoke 38 ALANNAH MYLES BLACK VELVET Karaoke -

DJ Song List by Song

A Case of You Joni Mitchell A Country Boy Can Survive Hank Williams, Jr. A Dios le Pido Juanes A Little Bit Me, a Little Bit You The Monkees A Little Party Never Killed Nobody (All We Got) Fergie, Q-Tip & GoonRock A Love Bizarre Sheila E. A Picture of Me (Without You) George Jones A Taste of Honey Herb Alpert & The Tijuana Brass A Ti Lo Que Te Duele La Senorita Dayana A Walk In the Forest Brian Crain A*s Like That Eminem A.M. Radio Everclear Aaron's Party (Come Get It) Aaron Carter ABC Jackson 5 Abilene George Hamilton IV About A Girl Nirvana About Last Night Vitamin C About Us Brook Hogan Abracadabra Steve Miller Band Abracadabra Sugar Ray Abraham, Martin and John Dillon Abriendo Caminos Diego Torres Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Nine Days Absolutely Not Deborah Cox Absynthe The Gits Accept My Sacrifice Suicidal Tendencies Accidentally In Love Counting Crows Ace In The Hole George Strait Ace Of Hearts Alan Jackson Achilles Last Stand Led Zeppelin Achy Breaky Heart Billy Ray Cyrus Across The Lines Tracy Chapman Across the Universe The Beatles Across the Universe Fiona Apple Action [12" Version] Orange Krush Adams Family Theme The Hit Crew Adam's Song Blink-182 Add It Up Violent Femmes Addicted Ace Young Addicted Kelly Clarkson Addicted Saving Abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted Sisqó Addicted (Sultan & Ned Shepard Remix) [feat. Hadley] Serge Devant Addicted To Love Robert Palmer Addicted To You Avicii Adhesive Stone Temple Pilots Adia Sarah McLachlan Adíos Muchachos New 101 Strings Orchestra Adore Prince Adore You Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel -

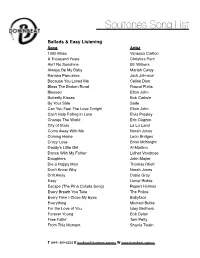

Soultones Song List 2020

Soultones Song List Ballads & Easy Listening Song Artist 1000 Miles Vanessa Carlton A Thousand Years Christina Perri Ain't No Sunshine Bill Withers Always Be My Baby Mariah Carey Banana Pancakes Jack Johnson Because You Loved Me Celine Dion Bless The Broken Road Rascal Flatts Blessed Elton John Butterfly Kisses Bob Carlisle By Your Side Sade Can You Feel The Love Tonight Elton John Can't Help Falling in Love Elvis Presley Change The World Eric Clapton City of Stars La La Land Come Away With Me Norah Jones Coming Home Leon Bridges Crazy Love Brian McKnight Daddy's Little Girl Al Martino Dance With My Father Luther Vandross Daughters John Mayer Die a Happy Man Thomas Rhett Don't Know Why Norah Jones Drift Away Dobie Gray Easy Lionel Richie Escape (The Pina Colada Song) Rupert Holmes Every Breath You Take The Police Every Time I Close My Eyes Babyface Everything Michael Buble For the Love of You Isley Brothers Forever Young Bob Dylan Free Fallin' Tom Petty From This Moment Shania Twain T (844) 369-6232 E [email protected] W www.downbeat.agency Soultones Song List Ballads & Easy Listening Song Artist Give Me One Reason Tracey Chapman God Must Have Spent NSYNC Gravity John Mayer Gypsy Fleetwood Mac Hallelujah Leonard Cohen Have I Told You Lately Rod Stewart Hello Adele Hey Jude The Beatles Ho Hey Lumineers I Choose You Sara Bareilles I Do Boyz II Men I Do Colbie Caillat I Don't Trust Myself John Mayer I Don't Want to Miss a Thing Aerosmith I Hope You Dance Lee Ann Womack I Like It DeBarge I Loved Her First Heartland I Wanna Know Joe I'll Be There Jackson 5 I'll Make Love To You Boyz II Men I'm Not The Only One Sam Smith I'm Yours Jason Mraz If I Ain't Got You Alicia Keys In My Life The Beatles In Your Eyes Peter Gabriel Just The Two Of Us Grover Washington Jr.