Fall / Winter 2013 Newsletter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

He Politics of Business in California 1890-1920 SI 2.50

he Politics of Business in California 1890-1920 SI 2.50 The Politics of Business in California. 1890-1920 Manse/ G. Blackford The American experience between the Civil War and World War I can perhaps be best understood as an attempt to reorder national life in the wake of a radical social and eco nomic disruption that was brought on by rapid industrialization. In California, even more than in other areas of the nation, fundamental and dramatic changes were to occur throughout the period as various sectors of the state's rapidly ex panding economy became both increasingly differentiated and more closely interdependent. Through a series of mergers and consolida tions, large, diversified, integrated, and multi level firms came to replace smaller, more specialized, independent, and single-level companies. Trade associations, marketing com bines, and other affiliations served to organize these emergent firms within each industry; and businessmen, acutely aware of a need for recognition of their status as members of a profession, began increasingly to act in con cert as a special-interest group, both in public, in their representations to legislative bodies, and in private, as apologists for commercial practice and as agents working to suppress competition and increase efficiency. Professor Blackford examines three of Cali fornia's more important basic productive in dustries—agriculture, oil, and lumber—and three of its principal supportive businesses — banking, investment banking, and insurance — together with two major issues that cut across industry lines: the growing movement to bring about state regulation of railroads and public utilities, and the effort to effect tax reform. -

The Cupola National Register of Historical Places

Oakland City Landmark 1975 The Cupola National Register of Historical Places Newsletter 1976 of the Alameda County Historical Society Landmark 1985 Pardee Home Museum California Historic Landmark Fall / Winter 2013 1998 PARDEE FAMILY DRESS MAKER Aura became a Modiste (dress sleds with wide runners so By Cherie Donahue designer) and had many well- that they would not sink into known clients including the the snow. On these was a Aura Prescott was born in a log Pardees. Aura designed and wagon-box. The bottom house on a Minnesota farm on sewed the beaded gown Mrs. was covered with straw and March 31, 1871. Her family George Pardee wore to the then hot stones and jugs of moved eight miles south to governor’s inaugural ball in hot water were placed and Albert Lea, Minnesota in 1876. Sacramento. This dress has all covered with blankets. This was the first time Aura had recently been located in storage The family was seated at ever seen a town. She and her in Sacramento. She spent six both sides and then more siblings could now attend weeks each summer in blankets. All the way the Sunday School and participate Sacramento in the Governor’s family would sing in concert. in group activities. In 1880 the Mansion while George Pardee Prescott’s moved to the newly Aura Prescott’s great was governor. opened Dakota Territory. Aura granddaughter, Cherie taught school in the Dakota Miss Helen and Miss Madeline Donohue, is a Pardee Home Territory before taking the train related memories of Aura living Museum board member, docent, to the 16th Street Station in at the family’s Oakland home and tea committee member. -

Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier Than the Pencil? Gerald F

Santa Clara Law Santa Clara Law Digital Commons Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 1-1-1992 Publication and Depublication of California Court of Appeal Opinions: Is the Eraser Mightier than the Pencil? Gerald F. Uelmen Santa Clara University School of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.law.scu.edu/facpubs Recommended Citation 26 Loy. L. A. L. Rev. 1007 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of Santa Clara Law Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. PUBLICATION AND DEPUBLICATION OF CALIFORNIA COURT OF APPEAL OPINIONS: IS THE ERASER MIGHTIER THAN THE PENCIL? Gerald F. Uelmen* What is a modem poet's fate? To write his thoughts upon a slate; The critic spits on what is done, Gives it a wipe-and all is gone.' I. INTRODUCTION During the first five years of the Lucas court,2 the California Supreme Court depublished3 586 opinions of the California Court of Ap- peal, declaring what the law of California was not.4 During the same five-year period, the California Supreme Court published a total of 555 of * Dean and Professor of Law, Santa Clara University School of Law. B.A., 1962, Loyola Marymount University; J.D., 1965, LL.M., 1966, Georgetown University Law Center. The author would like to acknowledge the assistance of Patrick Martucci, J.D., 1993, Santa Clara University School of Law, in the research for this Article. -

Constitutional Governance and Judicial Power- the History of the California Supreme Court

The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process Volume 18 Issue 1 Article 7 2017 Of Great Use and Interest: Constitutional Governance and Judicial Power- The History of the California Supreme Court Donald Warner Follow this and additional works at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess Part of the Courts Commons, Judges Commons, and the Legal History Commons Recommended Citation Donald Warner, Of Great Use and Interest: Constitutional Governance and Judicial Power- The History of the California Supreme Court, 18 J. APP. PRAC. & PROCESS 105 (2017). Available at: https://lawrepository.ualr.edu/appellatepracticeprocess/vol18/iss1/7 This document is brought to you for free and open access by Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Journal of Appellate Practice and Process by an authorized administrator of Bowen Law Repository: Scholarship & Archives. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 39639-aap_18-1 Sheet No. 57 Side A 11/15/2017 09:50:50 WARNEREXECEDIT (DO NOT DELETE) 10/24/2017 6:52 PM OF GREAT USE AND INTEREST: CONSTITUTIONAL GOVERNANCE AND JUDICIAL POWER—THE HISTORY OF THE CALIFORNIA SUPREME COURT* Donald Warner** I. INTRODUCTION Published under the auspices of the California Supreme Court Historical Society, this is a substantial and valuable effort by six authors (one of whom is also the editor) to provide a comprehensive history of the first 160 years—from 1850 through 2010—of the California Supreme Court. This Court has been, at times, among the most influential of the state courts of last resort,1 which would make almost any treatment of its history interesting to at least a few readers. -

Oral History Interview with Honorable Stanley Mosk

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with HONORABLE STANLEY MOSK Justice of the California Supreme Court, 1964-present February 18, March 11, April 2, May 27, July 22, 1998 San Francisco, California By Germaine LaBerge Regional Oral History Office University of California, Berkeley RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATIONS This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of this manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or the Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 1020 0 Street, Room 130 Sacramento, California 95814 or Regional Oral History Office 486 The Bancroft Library University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The request should include information of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Honorable Stanley Mosk Oral History Interview, Conducted 1998 by Germaine LaBerge, Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. INTERVIEW HISTORY InterviewerlEditor: Germaine LaBerge Editor, University of California at Berkeley State Archives State Government Oral History Program B.A. Manhattanville College, Purchase, New York (History) M.A. Mary Grove College, Detroit, Michigan (Education) Member (inactive), California State Bar Interview Time and Place: February 18, 1998, Session of one and a half hours. March 11, 1998, Session of one and a half hours. April 2, 1998, Session of one hour. May 27, 1998, Session of one hour. -

The California Recall History Is a Chronological Listing of Every

Complete List of Recall Attempts This is a chronological listing of every attempted recall of an elected state official in California. For the purposes of this history, a recall attempt is defined as a Notice of Intention to recall an official that is filed with the Secretary of State’s Office. 1913 Senator Marshall Black, 28th Senate District (Santa Clara County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Herbert C. Jones elected successor Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Failed to qualify for the ballot 1914 Senator Edwin E. Grant, 19th Senate District (San Francisco County) Qualified for the ballot, recall succeeded Vote percentages not available Edwin I. Wolfe elected successor Senator James C. Owens, 9th Senate District (Marin and Contra Costa counties) Qualified for the ballot, officer retained 1916 Assemblyman Frank Finley Merriam Failed to qualify for the ballot 1939 Governor Culbert L. Olson Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Citizens Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1940 Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot Governor Culbert L. Olson Filed by Olson Recall Committee Failed to qualify for the ballot 1960 Governor Edmund G. Brown Filed by Roderick J. Wilson Failed to qualify for the ballot 1 Complete List of Recall Attempts 1965 Assemblyman William F. Stanton, 25th Assembly District (Santa Clara County) Filed by Jerome J. Ducote Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman John Burton, 20th Assembly District (San Francisco County) Filed by John Carney Failed to qualify for the ballot Assemblyman Willie L. -

Kyle A. Casazza

Contact Kyle A. Casazza Partner Los Angeles +1.310.284.5677 [email protected] Kyle Casazza is a partner in the Litigation Department and a member of the Trial Strategies practice, where he focuses on all areas of complex commercial litigation. Kyle has significant plaintiff and defense-side experience in jury and bench trials in both state and federal courts. He has represented major companies in a wide array of industries, including oil and gas, financial services, media and entertainment, sports, technology and aerospace. Kyle has defended lawyers and law firms in connection with claims by both clients and non-clients arising from the performance of professional services. Kyle has worked on a number of civil and criminal antitrust matters, representing clients both in court and with the Department of Justice, most recently representing the Pac-12 Conference in antitrust litigation. He has also participated in internal accident investigations for aerospace companies. Kyle graduated from the USC Gould School of Law in May 2007, where he was awarded the Law Alumni Award (highest GPA in graduating class), the Alfred I. Mellenthin Award (highest GPA at the conclusion of the first and second years), the Judge Malcolm Lucas Award (highest GPA at the conclusion of the first year), and the Arthur Manella Scholarship (2005-06, 2006-07). While at USC, Kyle served as a senior submissions editor for the Southern California Law Review and as an Proskauer.com executive editor for a symposium issue of the Harvard Journal of Law & Public Policy . Following graduation, Kyle clerked for the Honorable Sandra Segal Ikuta, U.S. -

Public Comments on Supreme Court Proposal to Amend Cal. Rules Of

Public Comments on Supreme Court Proposal to Amend Cal. Rules of Court, rules 8.1105 and 8.1115 All comments are verbatim unless indicated by an asterisk (*) or brackets ([]). List by alpha.. Commentator Position Comment 1. Appellate Defenders, Inc. A Appellate Defenders, Inc., submits these comments on the proposed amendments to California Rules of Elaine A. Alexander, Executive Court, rules 8.1105 and 8.1115, which would change the rules on publication and citation of cases that Director; and Staff Attorneys have been granted review. ADI is the appointed counsel administrator for the Fourth Appellate District. It Loleena Ansari, Howard Cohen, Cheryl selects counsel for indigents on appeal in the district and oversees the representation provided. All counsel Geyerman, Helen Irza in its program have a stake in what constitutes citable and binding precedent. San Diego, CA Proposal that opinions remain citable after grant of review ADI supports the proposal that cases would retain their publication status after a grant of review. There is considerable value to having an opinion freely citable for its persuasive value and reasoning. It is a way of facilitating the best and most informed decision-making possible while lower courts and litigants and the public wait the year or two or more for the Supreme Court to resolve the underlying issue. Well thought out intermediate court decisions will help the Supreme Court reach a sound conclusion, as well. Of course, ADI agrees a case’s review-granted status must be noted prominently. On these points we seem to have the agreement of the other 49 states and the federal courts, according to the Invitation to Comment. -

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Jerry's Judges And

CALIFORNIA STATE UNIVERSITY, NORTHRIDGE Jerry's Judges and the Politics of the Death Penalty: The Judicial Election of 1986 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Master of Arts In History By Joseph Makhluf May 2011 The thesis of Joseph Makhlufis approved: Thomas Maddux, PhD. Date Andrea Henderson, PhD. Date Josh Sides, PhD., Chair Date California State University, Northridge 11 Table of Contents Signature Page 11 Abstract IV Introduction 1 Chapter 1: The California Supreme Court, 1978-1982 5 Chapter 2: The 1978 Gubernatorial Election 10 Chapter 3: TheNew Right Attack on the Courts 14 Chapter 4: The Death Penalty in the United States 20 Chapter 5 The 1982 Gubernatorial Election 22 Chapter 6: The Death Penalty Cases 34 Chapter 7: The Rose Bird Court and the Death Penalty 36 Chapter 8: The Judicial Election of 1986 40 Chapter 9: The Business Cases 58 Chapter 10: ANew California 63 Chapter 11 : The Verdict 71 Bibliography 73 lll Abstract Jerry's Judges and the Politics of the Death Penalty: The Judicial Election of 1986 By Joseph Makhluf Master of Arts in History On February 12, 1977, California Governor Jerry Brown nominated Rose Elizabeth Bird as chief justice ofthe California Supreme Court, making her the first female member of the court. Throughout her tenure on the Court, Bird faced criticism over her stance on important economic and social issues facing the state such as Proposition 13 and the death penalty. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s numerous California politicians campaigned on law-and-order and anti-tax issues, and accusations of pro-defendant and anti-Proposition 13 rulings became the latest and most popular criticism of the Court by those such as Howard Jarvis and Attorney General George Deukmejian who would work hard to remove her and her liberal colleagues from the California Supreme Court. -

![Justice Charles Vogel [Charles Vogel 6260.Doc]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9596/justice-charles-vogel-charles-vogel-6260-doc-2729596.webp)

Justice Charles Vogel [Charles Vogel 6260.Doc]

California Appellate Court Legacy Project – Video Interview Transcript: Justice Charles Vogel [Charles_Vogel_6260.doc] Charles Vogel: My title – my former title, you mean? David Knight: Sure. Charles Vogel: Okay. I am, and was, Administrative Presiding Justice of the Court of Appeal, Second District. My name is Charles S. Vogel. My last name is spelled V (as in Victor)–o-g-e-l. David Knight: Wonderful. Justice Rubin. Laurence Rubin: Okay. Today is September 23, 2008. I am Larry Rubin, and I’m an associate justice on the California Court of Appeal, Second District, Division Eight. It is my great privilege to interview Justice Charles S. Vogel, retired Administrative Presiding Justice of the Second District and Presiding Justice of the court’s Division Four. This interview is part of the Legacy Project of the Court of Appeal and is produced by David Knight of the Administrative Office of the Courts. Good afternoon, Justice Vogel. Charles Vogel: Good afternoon, Larry. Laurence Rubin: Most judges – and certainly most attorneys – would probably associate you with complex business and civil cases, speaking of when you were a justice on the Court of Appeal, president of the state and county bar, head of the ABTL, law-and-motion judge, Sidley & Austin – the whole gamut of your background. I went back to 1972 and found kind of an interesting quote, I thought. And you said at the time, “Contrary to other respectable opinion, I think it’s better for a judge if he doesn’t heavily specialize in one field of law. If you’re constantly dealing with people charged with crimes, for example, you may get too callous. -

Oral History Interview with Frank C. Newman

California State Archives State Government Oral History Program Oral History Interview with FRANK C. NEWMAN Professor of Law, University of California, Berkeley, 1946-present Justice, California Supreme Court, 1977--1983 January 24, Februrary 7, March 30, November 28, 1989; April 16, May 7, June 10, June 18, June 24, July 11, 1991 Berkeley, California By Carole Hicke Regional Oral History Office University of California, Berkeley RESTRICTIONS ON THIS INTERVIEW None. LITERARY RIGHTS AND QUOTATIONS This manuscript is hereby made available for research purposes only. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the California State Archivist or Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley. Requests for permission to quote for publication should be addressed to: California State Archives 201 N. Sunrise Avenue Roseville, California 95661 or Regional Oral History Office 486 Library University of California Berkeley, California 94720 The request should include information of the specific passages and identification of the user. It is recommended that this oral history be cited as follows: Frank C. Newman, Oral History Interview, Conducted 1989 and 1991 by Carole Hicke, Regional Oral History Office, University of California at Berkeley, for the California State Archives State Government Oral History Program. California State Archives (916) 773-3000 Office of the Secretary of State 201 No. Sunrise Avenue (FAX) 773-8249 March Fong Eu Sacramento, California 95661 PREFACE On September 25, 1985, Governor George Deukmejian signed into law A.B. 2104 (Chapter 965 of the Statutes of 1985). This legislation established, under the administration of the California State Archives, a State Government Oral History Program "to provide through the use of oral history a continuing documentation of state policy development as reflected in California's legislative and executive history." The following interview is one of a series of oral histories undertaken for inclusion in the state program. -

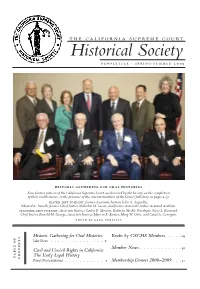

CSCHS Newsletter Spring/Summer 2009

The California Supreme Court Historical Society newsletter · s p r i n g / s u m m e r 2 0 0 9 Historic Gathering for Oral Histories Four former justices of the California Supreme Court are honored by the Society on the completion of their oral histories, in the presence of the current members of the Court (full story on pages 2–3). Seated, left to Right: former Associate Justices John A. Arguelles, Edward A. Panelli, former Chief Justice Malcolm M. Lucas, and former Associate Justice Armand Arabian. Standing, left to Right: Associate Justices Carlos R. Moreno, Kathryn Mickle Werdegar, Joyce L. Kennard, Chief Justice Ronald M. George, Associate Justices Marvin R. Baxter, Ming W. Chin, and Carol A. Corrigan. Photo by Greg Verville Historic Gathering for Oral Histories Books by CSCHS Members ��� ��� ��� ��� 29 Jake Dear ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 2 Member News ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 30 Civil and Uncivil Rights in California: The Early Legal History t a b l e o f c o n t e n t s Panel Presentations ��� ��� ��� ��� ��� 4 Membership Donors 2008–2009 ��� ��� ��� 31 Historic Gathering for Oral Histories By Jake Dear Chief Supervising Attorney, California Supreme Court our former members of the California Supreme said the Chief Justice. “Over a period of many years, oral FCourt were honored by the Society and the current history interviews have been conducted of Chief Jus- justices of the Court at a ceremony celebrating the com- tice Gibson, as well as Justices Carter, Mosk, Newman, pletion of the retired justices’ oral histories. Immedi- Broussard, Reynoso, and Grodin. Through these under- ately following the Court’s April 7, 2009, session in Los takings, we have literally preserved the living history Angeles, the Court joined with Society board members of the Court and its members.