Journal of Healthcare, Science and the Humanities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

Black Music, Gender & Sexuality

WGSS 391: Black Music, Gender & Sexuality Fumi Okiji [email protected] Tu/Th 10-11:15am Hasbrouck Laboratory, Room 130 Office hours: Tuesdays, 12-1:30pm, South College, W473 This course explores how black popular music cultures are shaped by performances and representations of gender and sexuality. The course will touch upon a number of themes including hip hop feminism, sex radicalism and camp, gender performativity and black masculinity. We will read music and film/video by artists such as Meshell Ndegeocello, Prince, Nicki Minaj, Bessie Smith and Beyonce as socio-historical texts that allow us access to an alternative source of knowledge supplementing the more theoretical. Students will be expected to build on their appreciation of black music to develop tools with which to critically engage with the expression, and with which to attend to the social, historical, performative and artistic complexes at play. This course fulfills critical race feminisms for UMass WGSS majors and minors. Offensive language and images You will be required to view, listen, think and talk about language, images and sounds that you might find offensive. This may include words and imagery that is sexist, homo- or transphobic, racist or obscene. It should go without saying that, I do not share or condone these words and actions. I do, however, believe that our engagement with these expressions is essential to an elucidation of the themes that underpin the course. It is important for each student to understand that by signing up to this course, you are agreeing to view and to listen to all material pertaining to it, regardless of its potentially offensive nature. -

Oxford Reference

Oxford Reference August 2019 Site Searches Alabama A&M University 5 Alabama Public Library Service 1 Alabama School of Fine Arts 4 Alabama School of the Deaf and Blind 1 Alabama Southern Community College 2 Alabama State University Library 4 Alabama Virtual Library Home Access 696 Alabama Youth Services Board of Education 1 Alexander City Board of Education 16 Amridge University 4 Athens State University 3 Auburn City Board of Education 2 Auburn University 147 Auburn University Montgomery Library 12 Baldwin County Board of Education 278 Birmingham Southern College 4 Blount County Board of Education 1 Boaz City Schools BOE 1 Calhoun County Board of Education 1 Chambers County Board of Education 1 Cherokee County Board of Education 1 Coffee County Board of Education 2 Colbert County Board of Education 2 Concordia College (NAAL Affiliate) 1 Covington County Board of Education 4 Crenshaw County Board of Education 13 Dallas County Board of Education 1 Decatur City Board of Education 2 Dothan City Board of Education 1 Elmore County Board of Education 1 Enterprise City Board of Education 10 Enterprise-Ozark Community College 3 Enterprise-Ozark Community College (Aviation Campus) 3 Fairhope Public Library 6 Faulkner University 70 Florence City Board of Education 1 Fort Payne City Board of Education 1 George C. Wallace Community College (Dothan - Main) 4 Hale County Board of Education 1 Haleyville City Board of Education 6 Hartselle City Board of Education 2 Homewood Public Library 3 Hoover City Board of Education 7 Hoover Public Library 1 1 Site Searches Huntingdon College Library 1 Huntsville City Board of Education 10 Jacksonville State University 3 Jefferson County Board of Education 12 Jefferson County Library Cooperative 58 John C. -

Informed Consent and Shared Decision Making in EBM

3 Informed Consent and shared decision making in EBM 3.1 ‘Informed consent’ in regular medical practice ‘Consent’ as it is understood in the medical context has to be asked from the pa- tient and is the explicit agreement to waive a right to certain rules and norms which are normally expected in the treatment of other people and of ourselves as patients. Every surgical procedure would, without consent from the patient, be legally un- derstood as assault and battery and the physician could be prosecuted for perform- ing it. ‘Informed consent’ therefore in its most simple form means that the patient has received a good explanation about a medical procedure, understands what is happening to him or her and then can make an informed choice to accept or refuse, in the latter case the so called ‘informed refusal.167 In order to give ‘informed con- sent the patient has to be capable of understanding the information given by the physician. He or she must be competent to decide and to give consent voluntarily without being coerced by any means into giving consent.168 ‘Autonomy’ of the patient, hereby equated with ‘person’ plays the overarching role in ‘informed con- sent.’ A competent person who exercises autonomy will have the final say about their own life. ‘Autonomy’ itself is a contested term in the philosophy of science and interpretations therefore vary. According to Dworkin, “Liberty (positive or negative) ... dignity, integrity, individuality, independence, responsibility and self knowledge ... self assertion ... critical reflection ... freedom from obligation ... ab- sence of external causation ... and knowledge of one’s own interests.”169 all fall under the definition of autonomy. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

Appendix B. Scoping Report

Appendix B. Scoping Report VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia VALERO CRUDE BY RAIL PROJECT Scoping Report Prepared for November 2013 City of Benicia 550 Kearny Street Suite 800 San Francisco, CA 94104 415.896.5900 www.esassoc.com Los Angeles Oakland Olympia Petaluma Portland Sacramento San Diego Seattle Tampa Woodland Hills 202115.01 TABLE OF CONTENTS Valero Crude By Rail Project Scoping Report Page 1. Introduction .................................................................................................................. 1 2. Description of the Project ........................................................................................... 2 Project Summary ........................................................................................................... 2 3. Opportunities for Public Comment ............................................................................ 2 Notification ..................................................................................................................... 2 Public Scoping Meeting ................................................................................................. 3 4. Summary of Scoping Comments ................................................................................ 3 Commenting Parties ...................................................................................................... 3 Comments Received During the Scoping Process ........................................................ 4 Appendices -

Presentation Abstracts

Eighth Annual Western Michigan University Medical Humanities Conference Conference Abstracts Hosted by the WMU Medical Humanities Workgroup and the Program in Medical Ethics, Humanities, and Law, Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine September 13-14, 2018 Our Sponsors: Western Michigan University Homer Stryker M.D. School of Medicine, WMU Center for the Study of Ethics in Society, WMU Department of Philosophy Ethics After Error: Malpractice, Mistrust, and the Limits of Medical Moral Repair Ben Almassi, PhD Division of Arts & Letters Governors State University Abstract: One limitation of medical ethics modelled on ideal moral theory is its relative silence on the aftermath of medical error – that is, not just on the recognition and avoidance of injustice, wrongdoing, or other such failures of medical ethics, but how to respond given medical injustice or wrongdoing. Ideally, we would never do each other wrong; but given that inevitably we do, as fallible and imperfect agents we require non-ideal ethical guidance. For such non-ideal moral contexts, I suggest, Margaret Walker’s account of moral repair and reparative justice presents powerful hermeneutical and practical tools toward understanding and enacting what is needed to restore moral relationships and moral standing in the aftermath of injustice or wrongdoing, tools that might be usefully extended to medical ethics and error specifically. Where retributive justice aims to make injured parties whole and retributive justice aims to mete out punishment, reparative justice “involves the restoration or reconstruction of confidence, trust, and hope in the reality of shared moral standards and of our reliability in meeting and enforcing them.” Medical moral repair is not without its challenges, however, in both theory and practice: standard ways of holding medical professionals and institutions responsible for medical error and malpractice function retributively and/or restitutively, either giving benign inattention to patient-practitioner relational repair or impeding it. -

Prudence Labeach Pollard, Ph.D., MPH, RD, SPHR

Prudence LaBeach Pollard, Ph.D., MPH, RD, SPHR Dr. Prudence LaBeach Pollard is Vice President for Research and Faculty Development and is a tenured Professor of Management in the School of Business at Oakwood University. She came to Oakwood University from La Sierra University where she served as a tenured Professor of Management in the School of Business and Management. Previous to La Sierra University she served Oakwood College as Vice-President for Administration, Planning and Human Resources, and as a professor at Andrews University and Loma Linda University. She is also an Examiner for the Malcolm Baldrige National Quality Awards. Dr. Pollard earned the Ph.D. in Evaluation, Measurement and Research Design from Western Michigan University. Her degree is applied to the research study of leadership behaviors of managers and executives in global organizations. While completing her Ph.D., Dr. Pollard was awarded the prestigious Women's Academic Achievement Award from Western Michigan University and was inducted by WMU into the Alpha Kappa Mu national honor society. She has taught leadership, management, policy and business research at Loma Linda University School of Public Health (Hawaii and Guam), Andrews University, Oakwood University, and La Sierra University. She graduated from Oakwood University in 1978, the University of Michigan School of Public Health in 1983, and Western Michigan University in 1993. Dr. Pollard is a Registered Dietitian and has also earned certification from the Society for Human Resource Management as a Senior Professional in Human Resources (SPHR). Dr. Pollard's professional career in management began at the Loma Linda University Medical Center. -

Devil in the Grove Review

CLSC BOOK REVIEW DEVIL IN THE GROVE BY GILBERT KING REPORTED BY MICHAEL J. GELFAND MONDAY JULY 6, 2015 How could this happen in America? It could not happen again, thank God? Two years ago, those were initial reactions to Gilbert King’s Pulitzer Prize winning history entitled Devil in the Grove. Why? Gilbert King writes of crimes in Groveland, Florida. These are in large part capital crimes. Accusations of rape that led to the death penalty. I could rhetorically state: what’s new? Before I proceed, please allow me a diversion, to shout: IT IS GREAT TO BE BACK AT CHAUTAUQUA! I have spoken from podiums, pulpits, bimas, risers, sidewalks and couches. The bucolic venues at Chautauqua are the most magnificent. The CLSC tradition on the Alumni Hall porch and lawn is splendid. Your consistent attention is amazing and appreciated, giving up your lunch hour on this busy day, between other lecturers who are truly outstanding. Thus, it is a special honor to return to this porch of literary and scientific renown yet another time, for which I extend my gratitude and appreciation to Jeff Miller. Jeff should be congratulated not just for his choice of speakers, but also for every year painstakingly dedication to the core principles of the CLSC, ensuring that our summers will challenge our minds and souls. Publication The CLSC teaches us to undertake critical analysis of the world around us and our communal and individual roles which are core Chautauquan values. As a side note, if literary criticism is an interest, then I urge you to seek out Mark Altshuler, and participate in his 16 year running Saturday Morning Short Story Discussion Course, a gem because it provides an intellectual tool, and charge to examine our roles, forcing us to forsake the witticisms of cable television’s talking heads, and to utilize the well tested tool of textual analysis, on Shabbat morning a secular typeFor of Torah study. -

Larouche Youth Join Amelia Boynton Robinson

Click here for Full Issue of EIR Volume 32, Number 11, March 18, 2005 EIRCivil Rights 40TH ANNIVERSARY OF SELMA’S ‘BLOODY SUNDAY’ LaRouche Youth Join Amelia Boynton Robinson by Bonnie James and Katherine Notley On the 40th anniversary of the historic crossing of Edmund 1965 Voting Rights Act was signed. Mr. Boynton died on Pettus Bridge in the Selma-to-Montgomery march for voting May 13, 1963, after suffering a series of strokes brought on rights, one of the movement’s great heroines, Amelia by the relentless threats to his and his family’s lives, to stop Boynton Robinson, invited four representatives of the him from organizing, as Mrs. Robinson describes in the inter- LaRouche Youth Movement to join her in Selma, Alabama view below, “for the ballot and the buck”—to secure voting to participate. The annual “Bridge Crossing Jubilee” to com- rights and economic independence for the county’s black citi- memorate “Bloody Sunday” on March 7, 1965, when state zens, many of them sharecroppers kept in a condition of vir- troopers attacked the demonstrators attempting to march tual slavery. His last words to his wife Amelia, were to ensure from Selma to the state capital in Montgomery, giving the that every African-American in Dallas County was registered date its infamous name, was hosted on March 3-6 by the to vote. National Voting Rights Museum in Selma, and culminated The LYM organizers joined Mrs. Robinson for a TV inter- on Sunday, March 6, with a re-enactment of the bridge view, in she which recounted her experiences in the voting crossing. -

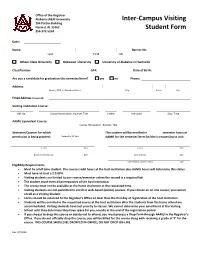

Inter-Campus Visiting Student Form

Office of the Registrar Alabama A&M University Inter-Campus Visiting 204 Patton Building Normal, AL 35762 Student Form 256-372-5254 Date: Name: Banner No. Last First MI Athens State University Oakwood University University of Alabama in Huntsville Classification: GPA: Date of Birth: Are you a candidate for graduation this semester/term? yes no Phone: Address: Route, POB, or Number/Street City State Zip Email Address (required): Visiting Institution Course: Ref. No. Course Abbreviation, Number, Title Credits Instructor Day / Time AAMU Equivalent Course: Course Abbreviation, Number, Title Semester/Quarter for which This student will be enrolled in semester hours at permission is being granted: Semester & Year AAMU for the semester/term he/she is requesting to visit. Student Date Advisor Date Department Chairperson Date Dean of School Date Vice President, Academic Affairs Date Eligibility Requirements Must be a full-time student. The course credit hours at the host institution plus AAMU hours will determine this status. Must have at least a 2.0 GPA. Visiting students are limited to one course/semester unless the second is a required lab. The student must meet all prerequisites of the host institution. The course must not be available at the home institution at the requested time. Visiting students are not permitted to enroll in web-based (online) courses. If you choose an on-line course; you cannot enroll as a Visiting Student. Forms should be returned to the Registrar’s Office no later than the first day of registration at the host institution. Students will be enrolled in the requested course at the host institution after the students from the home school are accommodated. -

I've Seen the Promised Land: a Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Mauricio E

SURGE Center for Public Service 1-20-2014 I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Mauricio E. Novoa Gettysburg College Follow this and additional works at: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge Part of the African American Studies Commons, Cultural History Commons, Inequality and Stratification Commons, Latin American Languages and Societies Commons, Latin American Studies Commons, Oral History Commons, Race and Ethnicity Commons, Social History Commons, and the United States History Commons Share feedback about the accessibility of this item. Novoa, Mauricio E., "I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson" (2014). SURGE. 43. https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/43 This is the author's version of the work. This publication appears in Gettysburg College's institutional repository by permission of the copyright owner for personal use, not for redistribution. Cupola permanent link: https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/surge/43 This open access blog post is brought to you by The uC pola: Scholarship at Gettysburg College. It has been accepted for inclusion by an authorized administrator of The uC pola. For more information, please contact [email protected]. I've Seen the Promised Land: A Letter to Amelia Boynton Robinson Abstract You asked if I had any thoughts or comments at the end of our visit, and I stood and said nothing. I opened my mouth, but instead of giving you words my throat was sealed by a dam of speechlessness while my eyes wept out all the emotions and heartache that I wanted to share with you. The others in my group were able to express their admiration, so I wanted to do the same.