FF 2019-2 A4 Pages Inc Covers DONE.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

News Letter January 2012

NEWS LETTER JANUARY 2012 DICKERSON HISTORY A Historical Review Committee consisting of Barry Creighton, Paula and Jim Karr, D and Don Wogaman and the writer has compiled a Historical Review of Dickerson Boatbuilders from it’s humble beginning at Bill Dickerson’s back yard at Church Creek, Maryland in 1946 to Trappe and the building of the last Dickerson in 1987. The Dickerson Owners web site http://dickersonowners.org/ features a short video of this fabulous history and a 16 page document with photos. At the 2012 Dickerson Rendezvous, June 15-17, we will celebrate the Dickerson Boatbuilders by inviting those that are still with us and the relatives of those that have moved on to visit with us and join in this celebration. In compiling this history, it was heartwarming to talk to the relatives of those that have passed on like Preston Brannock and Donald Griffin and those that are still with us like Tom Lucke, Ted Reed and our own Jim and Paula Karr (who played such active roles in the organization and got married while working for the Dickerson firm). Following is a note that we received from Ted Reed who bought Dickerson Boatbuilders in December of 1978 with his friend Bennett Dorrance and built the D-37, D-50, and Farr 37 in addition to the D-41 and D-36; started a charter service, and built a new marina. Joe Slavin, “Irish Mist” “Dear Joe, First I want to thank you and the others involved in compiling the Dickerson History and keeping the Dickerson Association alive and well. -

The Practical Tender & Fun Sailing Boat

2015/2 The Journal of the Ocean Cruising Club 301 Boatyard Or Backyard Rolling and Tipping with Epifanes Delivers Exceptional Results. Professional or amateur, once you’ve rolled and tipped a boat with Epifanes two-part Poly-urethane, it will be your go-to strategy for every paint job. The results are stunning, and Epifanes’ tech support is unsurpassed. Still great for spraying, but Epifanes roll-and-tip is the proven shortcut to a durable, mirror-like finish. Yacht Coatings AALSMEER, HOLLAND Q THOMASTON, MAINE Q ABERDEEN, HONG KONG +1 207 354 0804 Q www.epifanes.com FOLLOW US A special thank-you to the owners of Moonmaiden II. Beautiful paint job. 302 OCC FOUNDED 1954 offi cers ADMIRAL Mary Barton COMMODORE John Franklin VICE COMMODORES Tony Gooch Anne Hammick REAR COMMODORES Dick Guckel Peter Paternotte REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES GREAT BRITAIN Jenny Crickmore-Thompson IRELAND John Bourke NORTH WEST EUROPE Claus Jaeckel NORTH EAST USA Pam MacBrayne & Denis Moonan SOUTH EAST USA Bob & Janellen Frantz WEST COAST NORTH AMERICA Ian Grant NORTH EAST AUSTRALIA Nick Halsey SOUTH EAST AUSTRALIA Paul & Lynn Furniss ROVING REAR COMMODORES Scott & Kitty Kuhner, John & Christine Lytle, Chris Cromey & Suzanne Hills, Simon Fraser & Janet Gayler, Martin & Elizabeth Bevan, Rick & Julie Palm, David & Juliet Fosh, Jack & Zdenka Griswold, Alan Franklin & Lynne Gane, Franco Ferrero & Kath McNulty PAST COMMODORES 1954-1960 Humphrey Barton 1960-1968 Tim Heywood 1968-1975 Brian Stewart 1975-1982 Peter Carter-Ruck 1982-1988 John Foot 1988-1994 Mary Barton 1994-1998 -

News Letter October 2012

NEWS LETTER OCTOBER 2012 Dickerson Sailors Battle Strong Winds Wow, what a Western Shore Round-Up! The fleet for the Dickerson Sixth Western Shore Round-Up at West River battled 15-20 knot winds with gusts up to 25 knots during the September 8 th Race. Our Commodore Pat Ewing lost the mast of his wooden 40 foot Dickerson Ketch “VelAmore ” when a bronze turnbuckle broke. Pat with his young crew did an amazing job cleaning up the mess and getting back to port under power. We are all thankful that no one was hurt. Our appreciation goes to Dickerson Captains Barry Creighton “Crew Rest ” and Rick Woytowich “Belle ” who were racing near “ VelAmore ” when it’s mast and rigging went down and immediately withdrew from the race to help Pat get safely to shore. After the race, the Dickerson fleet, at the dock or on a mooring, survived a severe squall with torrential rain. 1 Left to right: Jim and John Freal, Sheriff Parker Hallam, Randy Bruns and Peter Oetker Our thanks to Randy and Barb Bruns for organizing this terrific event. The Friday night cook out at the West River Sailing Club and the Awards Dinner at Pirates Cove Restaurant went off perfectly with plenty of good cheer and all were certainly thankful to be safe. Congratulations go to the new Sheriff of the Western Shore Parker Hallam, 36 sloop “Frigate Connie ,” who won overall and also won the 35/36 class. New member Peter Oetker’s 39 sloop “Vignette ” won the 39-41 class and Bill Toth’s “ Starry Night ” won the 37 class. -

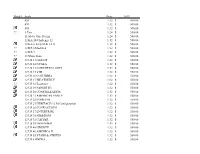

High-Low-Mean PHRF Handicaps

UNITED STATES PERFORMANCE HANDICAP RACING FLEET HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS IMPORTANT NOTE The following pages list low, high and average performance handicaps reported by USPHRF Fleets for over 4100 boat classes/types. Using Adobe Acrobat’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>, information can be displayed for each boat class upon request. Class names conform to USPHRF designations. The source information for this listing also provides data for the annual PHRF HANDICAP listings (The Red, White, & Blue Book) published by the UNITED STATES SAILING ASSOCIATION. This publication also lists handicaps by Class/Type, Fleet, Confidence Codes, and other useful information. Precautions: Handicap data represents base handicaps. Some reported handicaps represent determinations based upon statute rather than nautical miles. Some of the reported handicaps are based upon only one handicapped boat. The listing covers reports from affiliated fleets to USPHRF for the period March 1995 to June 2008. This listing is updated several times each year. HIGH, LOW, AND AVERAGE PERFORMANCE HANDICAPS ORGANIZED BY CLASS/TYPE Lowest Highest Average Class\Type Handicap Handicap Handicap 10 METER 60 60 60 11 METER 69 108 87 11 METER ODR 72 78 72 1D 35 27 45 33 1D48 -42 -24 -30 22 SQ METER 141 141 141 30 SQ METER 135 147 138 5.5 METER 156 180 165 6 METER 120 158 144 6 METER MODERN 108 108 108 6.5 M SERIES 108 108 108 6.5M 76 81 78 75 METER 39 39 39 8 METER 114 114 114 8 METER (PRE WW2) 111 111 111 8 METER MODERN 72 72 72 ABBOTT 22 228 252 231 ABBOTT 22 IB 234 252 -

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes Installation Drawing Available Configuration May Be Boat-Dependent

INSTALLATION LISTING * Denotes installation drawing available Configuration may be boat-dependent BOAT MODEL SHAFT BRACKETS 7 Seas Sailer 37.5 ft ketch* M HE Able 42* M+5 HE Acadian 30* M HE Acapulco 40 (Islander) L HE Accent 28 S HE Accord 36 M HH Achilles 24 S HE Achilles 840 M EH Achilles 9m M EH Adams 35* M EH Adams 40 M HE Adams 45 M EH Adams 45/12.7T* X HH Afrodita 2 1/2 (Cal 2‐46)* X HE Alaska 42 L EH Alberg 29* M HE Alberg 30 M HE Alberg 34* M HE Alberg 35 S HE Alberg 37* M HE Albin Ballad* M EH Albin Vega* S HE Alden 42 yawl* S HA Alden 45/51* X HA Alden 50* X HE Alden 50* X+5 HA Alden Challenger 39* M HA Allegro 33 ‐ off center M HH Allen Pape 43* L HE Allied mistress MK III 42 ketch L HE Allied Princess* L HH Allied Seawind 32 Ketch* M HE Allures 45 S AH Älo 33* M EH Aloha 28* S EH Aloha 30* M EH Alpa 11.5* M EH Alubaat Ovni 495 S‐10 AH Aluboot BV L EH Aluminium 48 X HH Aluminum Peterson 44 racer X AH Amazon 37 L HA Amazon 37* L HE Amel 48 ketch X EH Amel 54 L AH Amel Euros 39* L HE Amel Euros 41* L HH Amel Mango* L HA Amel Maramu 46 and 48* L HH Amel Santorin X EH Amel Santorin 46 Ketch* L EH Amel Sharki 39 L EH Amel Sharki 39 M EH Amel Sharki 40 L EH Amel Sharki* L EH Amor 40* L HE Amphitrite 43/12T* X+15 HA Angleman Ketch* L HE Ankh 44* M HE Apache 41 L HH Aphrodite 36* L EH Aphrodite 40* L EH Aquarius 24 L HE Aquatelle 149 X HA Arcona 40 DS* L EH or AH Arcona 400 L HA Arpege M EH Arpege (non‐reverse transom)* L HH Athena 38 L AH Atlanta 26 (Viking)* M HE Atlanta 28 M EH Atlantic 36* X EH Atlantic 38 Power Ketch* L HE Atlantic -

Pricesheet with Model Additions-Coallated

Model Scale Price 2019 420 1:12 ($ 500.00) 470 1:12 ($ 500.00) 505 1:12 ($ 500.00) ?? 1 Ton 1:24 ($ 550.00) 11 Meter One Design 1:24 ($ 550.00) 12 KA 10 Challenge 12 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 KA 6 AUSTRALIA II 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 KZ 3 Modified 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 KZ-7 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 Meter Kate 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 11 GLEAM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 12 NYALA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 14 NORTHERN LIGHT 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 15 VIM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 16 COLUMBIA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 17 WEATHERLY 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? 12 US 18 Easterner 1:32 ($ 850.00) 12 US 19 NEFERTITI 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 20 CONSTELLATION 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 21 AMERICAN EAGLE 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 22 INTREPID 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 23 HERITAGE-12 M Configuration 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 26 COURAGEOUS 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 27 ENTERPRISE 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 30 FREEDOM 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 32 CLIPPER 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 33 DEFENDER 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 40 LIBERTY 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 46 AMERICA II 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 55 STARS & STRIPES 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 6 ONIWA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 12 US 61 USA 1:32 ($ 550.00) 1D 35 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? 420 Jib 1:12 ($ 150.00) ?? 420 Sails 1:12 ($ 300.00) 470 w/ Sails 1:12 ($ 850.00) ?? 49er Skiff 1:24 ($ 550.00) Able Apogee 50 1:32 ($ 550.00) ?? Aerodyne 38 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Aerodyne 42 1:24 ($ 550.00) AGS-26 Class USN Survey Ship 1:92 ($ 550.00) Airco Distributor 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 30 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 35 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Alberg 36 1:24 ($ 550.00) Alberg 37 1:24 ($ 550.00) ?? Alberg C 22 1:24 ($ 550.00) Albin Nimbus 42 1:24 -

News Letter January 2014

NEWS LETTER JANUARY 2014 DICKERSON SAILORS RETURN TO THEIR ROOTS Honoring The Home Of A Bay Classic Dickerson sailors will celebrate their 47 th Annual Rendezvous, June 13-15 2014, with a Captains Party on Friday at the Yard where these classic boats were built in the mid 1960’s. Alan Willoughby, who worked at Dickerson Boatbuilders, will give presentations with films on the building of these historic boats. We are grateful to John Shannahan of Dickerson Harbor for assisting the Association in hosting this event. Dickerson Boatbuilders Plant and Marina 1984—now the site of Dickerson Harbor Plans for the Rendezvous also include a parade of Dickersons-- starting at 2 PM on Friday afternoon-- from Choptank Light to La Trappe Creek and Dickerson Harbor, the site of Dickerson Boatbuilders. On Saturday morning at 10 AM the traditional race will held on the Choptank using the New Handicap System which will be made available to racers with the race instructions. The Awards Dinner is planned to be held at 6 PM at the Tred Avon Yacht Club in Oxford on Saturday evening. Mark your calendar now and plan to participate in this very special celebration of Dickerson Boatbuilding. Additional information will be forth coming If you have any questions contact the Membership Committee at [email protected] Commodore Dave Fahrmeier D 41 “Down Home” DICKERSON SAILORS IN 2013 Commodore Pat Ewing finalized June 14-16, Father’s Day weekend, for the 46 th Annual Rendezvous, a parade of historic Dickersons, race, dinner, and most important, the opening of the new Dickerson Exhibit at the historic Richardson Museum in Cambridge, Maryland. -

US Sailing Rig Dimensions Database

ABOUT THIS CRITICAL DIMENSION DATA FILE There are databases that record critical dimensions of production sailboats that handicappers may use to identify yachts that race and to help them determine a sailing number to score competitive events. These databases are associated with empirical or performance handicapping systems worldwide and are generally available from those organizations via internet access. This data file contains dimensions for some, but not all, production boats reported to USPHRF since 1995. These data may be used to support performance handicapping by affiliated USPHRF fleets. There are many more boats in databases that sailmakers and handicappers possess. The USPHRF Technical Subcommittee and the US SAILING Offshore Office have several. This Adobe Acrobat file contains data mostly supplied by USPHRF affiliated fleets, a few manufacturers, naval architects, and others making contributions to database. While this data file is generally helpful, it does contain errors of omission and inaccuracies that are left to users to rectify by sending corrections to USPHRF by way of the data form below. The form also asks for additional information that anticipates the annual fall data collection from USPHRF affiliated fleets. Return this form to the USPHRF Committee c/o US SAILING. How do you access information in this data file of well over 5000 records for a specific boat? Use Adobe Acrobat Reader’s ‘FIND” feature, <CTRL-F>. Information currently in the file will be displayed for each Yacht Type/Class upon request. _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ -

FF 2020-2 Pages @ A4 Inc Covers.Indd

22020/2020/2 ® TThehe JJournalournal ooff tthehe OOceancean CCruisingruising ClubClub 1 “I am not afraid of storms for I am learning to sail my ship.” —Louisa May Alcott 2 OCC FOUNDED 1954 offi cers COMMODORE Simon Currin VICE COMMODORES Daria Blackwell Paul Furniss REAR COMMODORE Zdenka Griswold REGIONAL REAR COMMODORES GREAT BRITAIN Beth & Bone Bushnell IRELAND Alex Blackwell NORTH WEST EUROPE Hans Hansell NORTH EAST USA Janet Garnier & Henry DiPietro SOUTH EAST USA Bill & Lydia Strickland WEST COAST NORTH AMERICA Liza Copeland CALIFORNIA & MEXICO (W) Rick Whiting SOUTH EAST AUSTRALIA Scot Wheelhouse ROVING REAR COMMODORES Nicky & Reg Barker, Suzanne & David Chappell, Guy Chester, Andrew Curtain, Fergus Dunipace & Jenevora Swann, Gavin French, Bill Heaton & Grace Arnison, Alistair Hill, Stuart & Anne Letton, Pam McBrayne & Denis Moonan, Simon Phillips, Sarah & Phil Tadd, Gareth Thomas, Sue & Andy Warman PAST COMMODORES 1954-1960 Humphrey Barton 1994-1998 Tony Vasey 1960-1968 Tim Heywood 1998-2002 Mike Pocock 1968-1975 Brian Stewart 2002-2006 Alan Taylor 1975-1982 Peter Carter-Ruck 2006-2009 Martin Thomas 1982-1988 John Foot 2009-2012 Bill McLaren 1988-1994 Mary Barton 2012-2016 John Franklin 2016-2019 Anne Hammick SECRETARY Rachelle Turk Westbourne House, 4 Vicarage Hill Dartmouth, Devon TQ6 9EW, UK Tel: (UK) +44 20 7099 2678 Tel: (USA) +1 844 696 4480 e-mail: [email protected] EDITOR, FLYING FISH Anne Hammick Tel: +44 1326 212857 e-mail: [email protected] OCC ADVERTISING Details page 196 OCC WEBSITE www.oceancruisingclub.org 1 CONTENTS PAGE Editorial 3 A Second Try at the South 5 Randall Reeves Retreat From Paradise 18 Daria Blackwell Lessons Learned 28 Alex Blackwell Sending Submissions to Flying Fish 32 An Unfortunate Evening in Brittany 35 Brian Hall The 19th Hole 39 Graham & Avril Johnson From the Galley of .. -

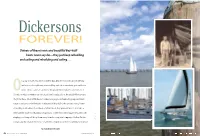

Dickersons FOREVER!

Dickersons FOREVER! Owners of these iconic and beautiful Bay-built boats never say die—they just keep rebuilding and sailing and rebuilding and sailing . Dickerson Owners Association n a day in June very close to Fathers Day, Dickerson owners all over the Bay and in several neighboring states will lay aside their varnishing pots and boar- Jody Schroath Argo Obristle brushes and set sail for the Choptank River. It won’t matter whether it’s still snowing or whether an early hurricane is taking aim at the middle Chesapeake, they’ll be there. After all, Dickerson owners are people undaunted by perpetual main- tenance and acres of brightwork, so why would they balk at the prospect of 12 hours of working to windward in 30 knots of wind? Heck, they probably won’t even take a reef. Like the swallows returning to Capistrano or the eels to the Sargasso Sea, they will simply go; nothing will keep them away from the congenial company of fellow Dicker- Jody Schroath Argo sonians and the shared experience of a lifetime of upkeep on their beautiful and beloved Dickerson Owners Association by Jody Argo Schroath 42 CHESAPEAKE BAY MAGAZINE June 2014 ChesapeakeBoating.net ChesapeakeBoating.net CHESAPEAKE BAY MAGAZINE June 2014 43 “proper” yachts. Some, like Al Sampson of Chris and Bill Burry of Queens Creek, Va., Bristol, R.I., owner of the 37-foot cutter have owned their Dickerson, Plover, for 30 Wanderlust, may occasionally come without years. “We sailed to Europe and back in the 80s their boats because . well, he’s in Rhode and thought we’d sell her when we got back,” BELOW: The beautiful 59-foot Island. -

Dickerson 47

Dickerson 47 P:r r*c r ttL Dr r,tlr apx3 4l'-c" D..Fr {'- e" ,u( 1t. J t DICKtrRSON BOATBUILDtrRS, TNC. Trappe, Maryland 21673 (30r) 476-3r 64 DESIGN, SPECIFICATIONS AND STANDARDS: HULL HandJayed up fiberglass, mat and roving All internal bulkheads of marine A-A grade plywood taped and bonded to the hull Full length molded keel DECK Fiberglass, covered A-A marine fir plywood 2xZvertical grain fir deck stringers Both stringers and deck bolted to integral hull flange BALLAST 8,500 pounds of lead, ingots fiberglassed internally to keel RUDDER Full Draft cruising rudder with internal prop alley MECHANICAL Westerbeke 40 Fresh water cooled Water cooled exhaust 3 blade cruising prop Tachometer, oil pressure, water temp., and ammeter 8au8es Throttle and shift controls with removable handles 50 gallon fuel tank Vent system in compliance with USCG regulations 100 gallon water capacity Pressure water throughout ELECTRICAL Two 12 VAC batteries with A position vapor proof switch 6 Function switch panel 11 interior lights Fluorescent galley light Port and starboard running lights Stern light Anchor light AFT CABIN Large double berth with storage below Bureau area Hanging locker Enclosed head with pressure water, vanity, and locker Linen closet Companionway to deck ENGINE ROOM Two large opening doors with full access Interior light Extra Room for refrigeration and auxiliary Senerator ENGINE Connects aft cabin and main cabin COMPANIONWAY Storage for tools and spare parts Formica counters and work area MAIN CABIN Companionway Wet locker GALLEY Walk-in U-shaped area with 3 burner stove and over (Gimbelled) Large 1OO lb.