1977 Nba Finals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pepperdine University- Half Court Shot for Tuition Sweepstakes- Long Form Rules 02-25-2021 (002).Docx Rules 02/09/2021

UNIVERSITY CREDIT UNION HALF-COURT SHOT FOR PEPPERDINE’S TUITION ON 2-25-2021 SWEEPSTAKES OFFICIAL RULES (1) NO PURCHASE OR PAYMENT OF ANY KIND IS NECESSARY TO ENTER OR WIN. A PURCHASE WILL NOT INCREASE YOUR CHANCES OF WINNING. THIS SWEEPSTAKES IS SUBJECT TO ALL APPLICABLE FEDERAL AND STATE LAWS AND REGULATIONS AND IS VOID WHERE PROHIBITED BY LAW. BY ENTERING THE SWEEPSTAKES, EACH ENTRANT AGREES TO BE BOUND BY THESE OFFICIAL RULES AND THE DECISIONS OF UNIVERSITY CREDIT UNION, WHICH ARE FINAL WITH RESPECT TO ALL MATTERS RELATING TO THE SWEEPSTAKES. (2) CONSUMER DISCLOSURE: Odds of winning are based upon the number of eligible entries received. Based upon the Credit Union’s estimate of 5,000 entries, odds of winning the Grand Prize are: 1 in 5,000. (3) SPONSOR: University Credit Union (“UCU”) is the sponsor of the Sweepstakes. UCU’s business address is 1500 S. Sepulveda Boulevard, Los Angeles, California 90025. (4) ELIGIBILITY: The Half-Court Shot for Pepperdine Tuition Sweepstakes (“Sweepstakes”) is only open to legal residents of the United States, US Territories, and the District of Columbia, eighteen (18) years of age or older and who are enrolled as full-time students at Pepperdine’s University, Malibu, California (“Santa Clara’s”) in an undergraduate program taking at least 12 units (“Entrant”) as of the date of entry. The Sweepstakes is NOT open to the following persons: (a) Current or former semi-professional, professional or Olympic-level basketball players who have competed at that level anywhere in the world at any time; (b) Current or former collegiate/university basketball players who have competed at that level anywhere in the world within the past five (5) years; (c) Current or former provincial or national team players who have competed at that level anywhere in the world within the past five (5) years; or (d) Current or former basketball coaches who have coached at the high school, college, semi-professional, professional or Olympic level within the past five (5) years. -

Remembrances and Thank Yous by Alan Cotler, W'72

Remembrances and Thank Yous By Alan Cotler, W’72, WG’74 When I told Mrs. Spitzer, my English teacher at Flushing High in Queens, I was going to Penn her eyes welled up and she said nothing. She just smiled. There were 1,100 kids in my graduating class. I was the only one going to an Ivy. And if I had not been recruited to play basketball I may have gone to Queens College. I was a student with academic friends and an athlete with jock friends. My idols were Bill Bradley and Mickey Mantle. My teams were the Yanks, the New York football Giants, the Rangers and the Knicks, and, 47 years later, they are still my teams. My older cousin Jill was the first in my immediate and extended family to go to college (Queens). I had received virtually no guidance about college and how life was about to change for me in Philadelphia. I was on my own. I wanted to get to campus a week before everyone. I wanted the best bed in 318 Magee in the Lower Quad. Steve Bilsky, one of Penn’s starting guards at the time who later was Penn’s AD for 25 years and who helped recruit me, had that room the year before, and said it was THE best room in the Quad --- a large room on the 3rd floor, looked out on the entire quad, you could see who was coming and going from every direction, and it had lots of light. It was the control tower of the Lower Quad. -

3 on 3 Tournament Rules

3 on 3 Tournament Rules All games must start with a minimum of 2 players per team. A minimum of 3 players must be registered to a maximum of 5 players per team. The game clock will begin at the scheduled time of the game whether teams are ready to play or not. All player names must appear on the scoresheet prior to the game beginning with the first player listed being 1 TEAM ROSTER designated as the "Team Captain" who will be the only player permitted to speak for the team. Games will be defaulted to the opposing team after five (5) minutes from the scheduled start of the game if the other team fails to provide the minimum of 2 players. A default will be recorded as a 1-0 win for the opposing team. The court supervisor will hold the final authority on the 'official time'. The dimensions of the 3on3 court will be played on a 'half-court' with a modified half-court line, sidelines and baseline being used as the playing surface. The traditional '3-point line' 2 THE COURT and the marked key will be used in all games. The top, sides, and bottom of the backboard are INBOUNDS. The metal support pieces from the top base unit to the backboard are OUT- OF-BOUNDS. 3 BALL SIZE A size 6 (28.5) basketball shall be used for all levels EXCEPT: 7th/8th Boys (regualaton) 4 GAME DURATION One, 25-minute game. No halftime. 5 INITIAL POSSESSION A coin flip shall determine which team gets the choice of first possession. -

WES MATTHEWS, Sr

Spring Break Basketball Camp Boys and girls grades 3rd to 8th (as of Sept. 2015) with 2-Time NBA Champion WES MATTHEWS, Sr. @ Derby Veterans Community Center 35 Fifth St. Derby, CT 06418 April 13th – 17th M – F 9am – 12pm April 13th – 17th M – F 1pm – 4pm Come learn, have fun and be coached by the best! Groups: Players grouped by JJV (3rd/4th g), JV (5th/6th g) and Varsity (7th/8th g) Schedule: Lecture; Stations; Team concepts/practice; Games Stations: includes customized skills development drills based on grade with individualized evaluation and instruction on all aspects of the game including leadership, team work, emotional preparation. discipline, work ethic and core conditioning Team concepts: Development of: knowledge, rules, language of the game, high basketball IQ, team offenses and defenses Games: Competitive scrimmages and games using indoor and outdoor courts $195 per player per session (includes camp shirt; discounts for siblings and double session registration) To register please visit: dribbledrivebasketball.net or complete this form Contact: Dennis Kelly 203-926-1365 phone Email: [email protected] Wes Matthews, Sr. Summary 2x NBA champion with the Lakers (1987 and 1988) Drafted 14th overall by the Washington Bullets in the 1980 NBA Draft Played with NBA standouts Michael Jordan, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Magic Johnson among others Best Import Award winner for the Ginebra San Miguel of the PBA (1991) Father of current NBA shooting guard Wes Matthews Jr. Bio Wes Matthews Sr. is a retired NBA guard who has played for six different NBA teams and in five professional basketball leagues throughout his career. -

2018-19 Phoenix Suns Media Guide 2018-19 Suns Schedule

2018-19 PHOENIX SUNS MEDIA GUIDE 2018-19 SUNS SCHEDULE OCTOBER 2018 JANUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 SAC 2 3 NZB 4 5 POR 6 1 2 PHI 3 4 LAC 5 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON PRESEASON 7 8 GSW 9 10 POR 11 12 13 6 CHA 7 8 SAC 9 DAL 10 11 12 DEN 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 6:30 PM 7:00 PM PRESEASON PRESEASON 14 15 16 17 DAL 18 19 20 DEN 13 14 15 IND 16 17 TOR 18 19 CHA 7:30 PM 6:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:30 PM 3:00 PM ESPN 21 22 GSW 23 24 LAL 25 26 27 MEM 20 MIN 21 22 MIN 23 24 POR 25 DEN 26 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 28 OKC 29 30 31 SAS 27 LAL 28 29 SAS 30 31 4:00 PM 7:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:30 PM 6:30 PM ESPN FSAZ 3:00 PM 7:30 PM FSAZ FSAZ NOVEMBER 2018 FEBRUARY 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 2 TOR 3 1 2 ATL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4 MEM 5 6 BKN 7 8 BOS 9 10 NOP 3 4 HOU 5 6 UTA 7 8 GSW 9 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 5:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 11 12 OKC 13 14 SAS 15 16 17 OKC 10 SAC 11 12 13 LAC 14 15 16 6:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 4:00 PM 8:30 PM 18 19 PHI 20 21 CHI 22 23 MIL 24 17 18 19 20 21 CLE 22 23 ATL 5:00 PM 6:00 PM 6:30 PM 5:00 PM 5:00 PM 25 DET 26 27 IND 28 LAC 29 30 ORL 24 25 MIA 26 27 28 2:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:30 PM 7:00 PM 5:30 PM DECEMBER 2018 MARCH 2019 SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT SUN MON TUE WED THU FRI SAT 1 1 2 NOP LAL 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 2 LAL 3 4 SAC 5 6 POR 7 MIA 8 3 4 MIL 5 6 NYK 7 8 9 POR 1:30 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 7:00 PM 8:00 PM 9 10 LAC 11 SAS 12 13 DAL 14 15 MIN 10 GSW 11 12 13 UTA 14 15 HOU 16 NOP 7:00 -

2019-20 Panini Flawless Basketball Checklist

2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals 281 Players with Cards; Hits = Auto+Auto Relic+Relic Only **Totals do not include 2018/19 Extra Autographs TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain A.C. Green 177 177 177 Aaron Gordon 141 141 141 Aaron Holiday 112 112 112 Admiral Schofield 77 77 77 Adrian Dantley 115 115 59 56 Al Horford 385 386 177 169 39 1 Alex English 177 177 177 Allan Houston 236 236 236 Allen Iverson 332 387 295 1 36 55 Allonzo Trier 286 286 118 168 Alonzo Mourning 60 60 60 Alvan Adams 177 177 177 Andre Drummond 90 90 90 Andrea Bargnani 177 177 177 Andrew Wiggins 484 485 118 225 141 1 Anfernee Hardaway 9 9 9 Anthony Davis 453 610 118 284 51 157 Arvydas Sabonis 59 59 59 Avery Bradley 118 118 118 B.J. Armstrong 177 177 177 Bam Adebayo 92 92 92 Ben Simmons 103 132 103 29 Bill Bradley 9 9 9 Bill Russell 186 213 177 9 27 Bill Walton 59 59 59 Blake Griffin 90 90 90 Bob McAdoo 177 177 177 Bobby Portis 118 118 118 Bogdan Bogdanovic 230 230 118 112 Bojan Bogdanovic 90 90 90 GroupBreakChecklists.com 2019-20 Flawless Basketball Player Card Totals TOTAL TOTAL Auto Relic Block Team Auto HITS CARDS Relic Only Chain Bradley Beal 93 95 93 2 Brandon Clarke 324 434 59 226 39 110 Brandon Ingram 39 39 39 Brook Lopez 286 286 118 168 Buddy Hield 90 90 90 Calvin Murphy 236 236 236 Cam Reddish 380 537 59 228 93 157 Cameron Johnson 290 291 225 65 1 Carmelo Anthony 39 39 39 Caron Butler 1 2 1 1 Charles Barkley 493 657 236 170 87 164 Charles Oakley 177 177 177 Chauncey Billups 177 177 177 Chris Bosh 1 2 1 1 Chris Kaman -

25 Misunderstood Rules in High School Basketball

25 Misunderstood Rules in High School Basketball 1. There is no 3-second count between the release of a shot and the control of a rebound, at which time a new count starts. 2. A player can go out of bounds, and return inbounds and be the first to touch the ball l! Comment: This is not the NFL. You can be the first to touch a ball if you were out of bounds. 3. There is no such thing as “over the back”. There must be contact resulting in advantage/disadvantage. Do not put a tall player at a disadvantage merely for being tall 4. “Reaching” is not a foul. There must be contact and the player with the ball must have been placed at a disadvantage. 5. A player can always recover his/her fumbled ball; a fumble is not a dribble, and any steps taken during recovery are not traveling, regardless of progress made and/or advantage gained! (Running while fumbling is not traveling!) Comment: You can fumble a pass, recover it and legally begin a dribble. This is not a double dribble. If the player bats the ball to the floor in a controlling fashion, picks the ball up, then begins to dribble, you now have a violation. 6. It is not possible for a player to travel while dribbling. 7. A high dribble is always legal provided the dribbler’s hand stays on top of the ball, and the ball does not come to rest in the dribblers’ hand. Comment: The key is whether or not the ball is at rest in the hand. -

Tiny Spaces Put Squeeze on Parking

TACKLING THE GAME — SEE SPORTS, B8 PortlandTribune THURSDAY, MAY 8, 2014 • TWICE CHOSEN THE NATION’S BEST NONDONDAILYONDAAILYILY PAPERPAPER • PORTLANDTRIBUNE.COMPORTLANDTRIBUNEPORTLANDTRIBUNE.COMCOM • PUBLISHEDPUBLISHED TUESDAYTUESDAY ANDAND THTHURSDAYURRSDSDAYAY ■ Coming wave of micro apartments will increase Rose City Portland’s density, but will renters give up their cars? kicks it this summer as soccer central Venture Portland funds grants to lure crowds for MLS week By JENNIFER ANDERSON The Tribune Hilda Solis lives, breathes, drinks and eats soccer. She owns Bazi Bierbrasserie, a soccer-themed bar on Southeast Hawthorne and 32nd Avenue that celebrates and welcomes soccer fans from all over the region. As a midfi elder on the Whipsaws (the fi rst fe- male-only fan team in the Timbers’ Army net- work), Solis partnered with Lompoc Beer last year to brew the fi rst tribute beer to the Portland Thorns, called Every Rose Has its Thorn. And this summer, Solis will be one of tens of thousands of soccer fans in Portland celebrating the city’s Major League Soccer week. With a stadium that fi ts just 20,000 fans, Port- land will be host to world championship team Bayern Munich, of Germany, at the All-Star Game at Jeld-Wen Field in Portland on Aug. 6. “The goal As fans watch the game in is to get as local sports bars and visitors fl ock to Portland for revelries, many fans it won’t be just downtown busi- a taste of nesses that are benefi ting from all the activity. the MLS Venture Portland, the city’s All-Star network of neighborhood busi- game ness districts, has awarded a The Footprint Northwest Thurman Street development is bringing micro apartments to Northwest Portland — 50 units, shared kitchens, no on-site parking special round of grants to help experience. -

Ucla Men's Basketball

UCLA MEN’S BASKETBALL March 25, 2006 Bill Bennett/Marc Dellins /310-206-7870 For Immediate Release UCLA Men’s Basketball/NCAA Between Game Notes NO. 7 UCLA PLAYS NO. 4 MEMPHIS IN NCAA REGIONAL FINAL IN OAKLAND ON SATURDAY, WINNER ADVANCES TO “FINAL FOUR” IN INDIANAPOLIS; BRUINS EDGE GONZAGA 73-71 ON THURSDAY IN “SWEET 16” CONTEST No. 7/No. 8 UCLA (30-6/Pac-10 14-4, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 2 Seed) vs. No. 4/No. 3 MEMPHIS (33-3/Conference USA 13-1, Regular Season, Tournament Champions/No. 1 Seed) - Saturday, March 25/Oakland, CA/Oakland Arena/4:05 p.m. PT/TV- CBS, Gus Johnson and Len Elmore/Radio-570AM, with Chris Roberts and Don MacLean. Tentative UCLA Starters F- 21 Cedric Bozeman 6-6, Sr., 7.8, 3.2 F-23 Luc Richard Mbah a Moute 6-8, Fr., 9.1, 8.1 C- 15 Ryan Hollins 7-01/2, Sr., 6.7, 4.5 G-1 Jordan Farmar 6-2, So., 13.6, 2.5 G-4 Arron Afflalo 6-4, So., 16.2, 4.3 UCLA vs. Memphis – The Tigers advanced with an 80-64 victory over Bradley, led by Rodney Carney’s 23 points. Memphis has won 22 of its last 23 games and has a seven-game winning streak. This will be the team’s second meeting this season – on Nov. 23 in New York City’s Madison Square Garden, Memphis defeated UCLA 88-80 in an NIT Season Tip-Off semifinal. Last Meeting - Nov. 23 – No. 11 Memphis 88, No. -

Renormalizing Individual Performance Metrics for Cultural Heritage Management of Sports Records

Renormalizing individual performance metrics for cultural heritage management of sports records Alexander M. Petersen1 and Orion Penner2 1Management of Complex Systems Department, Ernest and Julio Gallo Management Program, School of Engineering, University of California, Merced, CA 95343 2Chair of Innovation and Intellectual Property Policy, College of Management of Technology, Ecole Polytechnique Federale de Lausanne, Lausanne, Switzerland. (Dated: April 21, 2020) Individual performance metrics are commonly used to compare players from different eras. However, such cross-era comparison is often biased due to significant changes in success factors underlying player achievement rates (e.g. performance enhancing drugs and modern training regimens). Such historical comparison is more than fodder for casual discussion among sports fans, as it is also an issue of critical importance to the multi- billion dollar professional sport industry and the institutions (e.g. Hall of Fame) charged with preserving sports history and the legacy of outstanding players and achievements. To address this cultural heritage management issue, we report an objective statistical method for renormalizing career achievement metrics, one that is par- ticularly tailored for common seasonal performance metrics, which are often aggregated into summary career metrics – despite the fact that many player careers span different eras. Remarkably, we find that the method applied to comprehensive Major League Baseball and National Basketball Association player data preserves the overall functional form of the distribution of career achievement, both at the season and career level. As such, subsequent re-ranking of the top-50 all-time records in MLB and the NBA using renormalized metrics indicates reordering at the local rank level, as opposed to bulk reordering by era. -

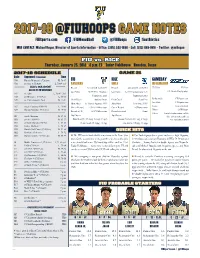

2017-18 @Fiuhoops Fiuhoops Game Notes Game Notes

22017-18017-18 @FFIUHOOPSIUHOOPS GGAMEAME NNOTESOTES FIUSports.com /FIUMensBball @FIUHoops fiuathletics MBB CONTACT: Michael Hogan, Director of Sports Information • Office: (305) 348-1496 • Cell: (813) 469-0616 • Twitter: @mihogan FFIUIU vvs.s. RRICEICE Thursday, January 25, 2018 • 8 p.m. ET • Tudor Fieldhouse • Houston, Texas 22017-18017-18 SSCHEDULECHEDULE GGAMEAME 2211 Date Opponent (Television) Time N10 Florida Memorial (CUSA.tv) W, 70-47 FIU RICE GAMEDAY N12 Stetson (CUSA.tv) L, 70-64 (ot) PANTHERS OWLS INFORMATION BLACK & GOLD SHOOTOUT Record 9-11 overall, 3-4 C-USA Record 4-16 overall, 1-6 C-USA TV/Video CUSA.tv HOSTED BY UW MILWAUKEE Last Game W, 79-59 vs. Charlotte Last Game L, 69-54 at Louisiana Tech J.P. Heath (Play-by-play) N17 vs. Elon L, 95-87 (3ot) N18 at Milwaukee (CUSA.tv) L, 66-51 January 20, 2018 January 20, 2018 Radio/Audio FIUSports.com N19 vs. Concordia-St. Paul W, 77-67 Head Coach Anthony Evans Head Coach Scott Pera Live Stats FIUSports.com Alma Mater St. Thomas Aquinas, 1994 Alma Mater Penn State, 1989 Series Series tied, 2-2 N27 South Carolina (CBSSN) L, 78-61 Career Record 159-181/11th season Career Record 1-6/First season N29 Florida National (CUSA.tv) W, 79-61 Twitter @FIUHoops Record at FIU 60-87/Fifth season Record at school Same Tickets For ticket information, call the Top Players Top Players D2 South Alabama W, 87-58 Rice athletic ticket offi ce at D11 at USF (ESPN3) W, 65-53 Brian Beard, Jr. (15.4 ppg, 5.4 apg, 3.2 spg) Connor Cashaw (16.1 ppg, 6.3 rpg) 713-348-OWLS (6957) D13 at North Florida (ESPN3) L, -

Saturday Specials!

PAGE TWENTY-FOUR - MANCHESTER EVENING HERALD. Manchester. Conn.. Fri,, March 22. 1974 Expert Offers Advice Minimum Wage Hike For Tree Treatment Called Peril to Jobs ilanrI|THtpr Eupning te a lb WASHINGTON (UPI) - The tie real increase in personal MANCHESTER, CONN., SATURDAY, MARCH 23, 1974 - VOL. XCIII, No. 147 ^fonchester A City o f Villume Chorm * s ix t e e n p a g e s _ BARBARA RICHMOND Dr. Schramm cautions this they should contact the nation’s workers may see the spendable income. TWO MINI PRICE: FIFI’EEN CENTS For those who have trees homeowners that massive Tolland County Extension Ser minimum wage go up to $2 an “The labor force will pay (for damaged by the December wounds caused by the breaking vice or an arborist who can ad hour by May, but a con the action) through more un ice storm, Dr. Robert J. off of tree tops and branches vise them. gressional opponent charges employment and more taxes,” Schramm, extension should be treated to prevent For those trees worth the action could backfire on said FTice. nurseryman at the Universi decay in cases where it may be treating, they should be pruned them by boosting unemployr President Nixon, who vetoed possible to save them. back to a main stem or trunk ment. similar legislation last year, ty of Connecticut, has words He said some trees and TTie House Wednesday voted of advice concerning treat- and the “wound” should be supported the measure, but shrubs may be beyond saving 375 to 27 to raise the minimum asked the House to make the Kissinger To Meet With Brezhnev itient of them.