Daphnandra Johnsonii, Atherospermataceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN of MANAGEMENT December 2019

Mt Keira Summit Park PLAN OF MANAGEMENT December 2019 The Mt Keira Summit Park Plan of Management was prepared by TRC Tourism Pty Ltd for Wollongong City Council. Acknowledgements Images used in this Plan are courtesy of Wollongong City Council, Destination Wollongong and TRC Tourism except where otherwise indicated. Acknowledgement of Country Disclaimer Wollongong City Council would like to show their Any representation, statement, opinion or advice, respect and acknowledge the traditional expressed or implied in this document is made in good custodians of the Land, of Elders past and present, faith but on the basis that TRC Tourism Pty. Ltd., and extend that respect to other Aboriginal and directors, employees and associated entities are not Torres Strait Islander people. liable for any damage or loss whatsoever which has occurred or may occur in relation to taking or not taking action in respect of any representation, statement or advice referred to in this document. ©Copyright TRC Tourism Pty Ltd www.trctourism.com Contents 1 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 1 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 1 1.2 Purpose of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ 2 1.3 Making of the Plan of Management ............................................................................................ -

Wagga Wagga Australia

OPENING NIGHT THE MAN WHO KNEW INFINITY FRIDAY 11 MARCH 7PM Directed by Matthew Brown | UK | In English and Tamil with English subtitles | 108 mins | PG SELECTED: TORONTO & DUBAI FILM FESTIVAL 2015 Based on the inspirational biography of a genuine mathematical genius in the early twentieth century, The Man Who Knew Infinity tells the life story of Srinivasa Ramanujan (Dev Patel, Slumdog Millionaire). Image: Mustang From an underprivileged upbringing in Madras, India, Ramanujan earns admittance to Cambridge University during WWI, where he becomes a pioneer in mathematical theories. Academy Award-winner Jeremy Irons delivers a terrific performance as Cambridge University Professor G.H. Hardy, who is inspired and captivated by the mathematician’s ground-breaking theories. Their friendship transcends race and culture through mutual respect and understanding, and Ramanujan’s visionary theories shine through the ignorance and prejudice of those around him. WAGGA WAGGA “Tells such a good story, it’s hard to resist.” – SCREEN DAILY “Highly engaging performances…an extraordinary story.” – THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER FORUM 6 CINEMAS Followed by complimentary Opening Night drinks and party. 11-13 MARCH 2016 SPECIAL SCREENING: SUBSCRIBE HOW CALL ME DAD AND SAVE TO BOOK SATURDAY 12 MARCH 10.30AM Save over 35% on regular ticket Book tickets online in advance at Directed by Sophie Wiesner | Australia | In English | 80 mins | M prices with a subscription - all sff.org.au/Wagga. The Travelling Film Festival and Good Pitch Australia present a special screening of Australian nine films for only $9 per film ($8 documentary, Call Me Dad, a story about men who have perpetrated, or are at risk of concession), including Opening For ticket enquiries please perpetrating, family violence. -

Albion Park & Kiama District

Bus Route Numbers Look for bus Albion Park Stockland Shellharbour to Kiama via numbers 71 Dunmore, Minnamurra, Kiama Downs & & Kiama Bombo. Service operates Monday–Saturday. District Shellharbour to Albion Park via Flinders & 71 Buses Serving 76 Warilla. Service operates 7 days. 76 Albion Park Stockland Shellharbour to Albion Park via Oak Flats 77 Oak Flats & Albion Park Rail. Warilla Service operates Monday–Saturday. 77 Flinders Shellharbour Minnamurra Kiama See back cover for detailed route descriptions Price 50c Effective from 11 October 2010 Additional Services There are additional services operating in this area. Region 10 Please call 131500 or visit Transport Info for details. Wollongong This service is operated by 13-23 Investigator Drive Your Outer Metropolitan Unanderra NSW 2526 Region 10 operator Ph: 4271 1322 www.premierillawarra.com.au ABN: 27 080 438 562 Premier Illawarra Timetable 71/76/77 | Version 6 | 11 October 2010 Kiama Route Shellharbour to Kiama 71 via Dunmore, Minnamurra, Kiama Downs & Bombo Monday to Friday map ref Route 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 71 am am am pm pm pm pm pm A Shellharbour (Stockland) .... 9.10 10.40 12.10 1.40 2.40 4.25 5.30 B Dunmore (Princes Hwy & Riverside Dr) .... 9.20 10.50 12.20 1.50 2.50 4.35 5.40 C Kiama Downs (Barton Dr & McBrien Dr) 8.26 9.26 10.56 12.26 1.56 2.56 4.41 5.46 D Minnamurra (Public School) 8.34 9.34 11.04 12.34 2.04 3.04 4.49 5.54 E Kiama Downs (North Kiama Dr & Riverside Dr) 8.43 9.43 11.13 12.43 2.13 3.13 4.58 6.02 F Kiama Leisure Centre 8.50 9.50 11.20 12.50 2.20 3.20 5.05 6.08 G Kiama Hospital (Bonaira St) 8.56 9.56 11.26 12.56 2.26 3.26 5.11 6.13 Saturday map ref Route 71 71 71 71 am am pm pm A Shellharbour (Stockland) ... -

Faculty of Engineering December 2007

University o f Wollong ong FACULTY OF ENGINEERING DECEMBER 2007 Dean’s Spot At this time of the year our academic lives. For Faculty hosts large numbers of example, in addition high school students who are to abilities in maths, The Faculty of trying to choose their career science and lan- Engineering and to decide what University guages, we are look- course and which University to ing for any examples would like to enrol in for 2008. Naturally we of leadership, crea- wish all its staff think that Engineering and tive, and imaginative Physics at University of Wollongong or other skills students may and students a offers a wide variety of challenging and have demonstrated. This may Merry Christmas worthwhile careers and so we are very be apparent in non academic and a Happy keen to convince as many students as areas such as sport, music, possible to come to our Faculty. Hence debating, social or other ac- New Year! we run an innovative and comprehensive tivities, either within school or ‘Early Entry’ program. outside of school. We are interested in each student as a com- high school students in their final year at This program was pioneered by Engi- plete person, as this is important in school. neering at Wollongong over 10 years ago, establishing whether or not someone and has now been adopted by most other The early entry program is a wonderful is likely to become a good engineer. Faculties here, and even by other Univer- team effort of staff and students from all sities, such as University of New South So far this year we have interviewed parts of the Faculty and everyone in- Wales, who introduced their own early over 300 people interested in joining volved is impressed with the enthusiasm entry scheme last year. -

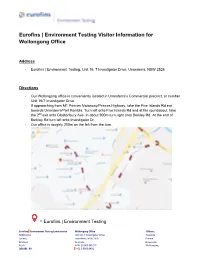

Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office

Eurofins | Environment Testing Visitor Information for Wollongong Office Address - Eurofins | Environment Testing, Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive, Unanderra, NSW 2526 Directions - Our Wollongong office is conveniently located in Unanderra’s Commercial precinct, at number Unit 16/7 Investigator Drive. - If approaching from M1 Princes Motorway/Princes Highway, take the Five Islands Rd exit towards Unanderra/Port Kembla. Turn left onto Five Islands Rd and at the roundabout, take the 2nd exit onto Glastonbury Ave. In about 900m turn right onto Berkley Rd. At the end of Berkley Rd turn left onto Investigator Dr. - Our office is roughly 200m on the left from the turn. = Eurofins | Environment Testing Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 Parking - There are 3 car spaces directly in front of the building, if the spaces are all occupied there is also on street parking out the front of the complex. General Information - The Wollongong office site includes a client services room available 24 hours / 7 days a week for clients to drop off samples and / or pick up bottles and stock. This facility available for Eurofins | Environment Testing clients, is accessed via a coded lock. For information on the code and how to utilize this access service, please contact Elvis Dsouza on 0447 584 487. - Standard office opening hours are between 8.30am to 5.00pm, Monday to Friday (excluding public holidays). We look forward to your visit. Eurofins | Environment Testing Management & Staff Eurofins Environment Testing Laboratories Wollongong Office Offices : Melbourne Unit 16, 7 Investigator Drive Adelaide Sydney Unanderra, NSW 2526 Darwin Brisbane Australia Newcastle Perth ABN: 50 005 085 521 Wollongong QS1081_R0 +61 2 9900 8492 . -

Reconstructing the Basal Angiosperm Phylogeny: Evaluating Information Content of Mitochondrial Genes

55 (4) • November 2006: 837–856 Qiu & al. • Basal angiosperm phylogeny Reconstructing the basal angiosperm phylogeny: evaluating information content of mitochondrial genes Yin-Long Qiu1, Libo Li, Tory A. Hendry, Ruiqi Li, David W. Taylor, Michael J. Issa, Alexander J. Ronen, Mona L. Vekaria & Adam M. White 1Department of Ecology & Evolutionary Biology, The University Herbarium, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, Michigan 48109-1048, U.S.A. [email protected] (author for correspondence). Three mitochondrial (atp1, matR, nad5), four chloroplast (atpB, matK, rbcL, rpoC2), and one nuclear (18S) genes from 162 seed plants, representing all major lineages of gymnosperms and angiosperms, were analyzed together in a supermatrix or in various partitions using likelihood and parsimony methods. The results show that Amborella + Nymphaeales together constitute the first diverging lineage of angiosperms, and that the topology of Amborella alone being sister to all other angiosperms likely represents a local long branch attrac- tion artifact. The monophyly of magnoliids, as well as sister relationships between Magnoliales and Laurales, and between Canellales and Piperales, are all strongly supported. The sister relationship to eudicots of Ceratophyllum is not strongly supported by this study; instead a placement of the genus with Chloranthaceae receives moderate support in the mitochondrial gene analyses. Relationships among magnoliids, monocots, and eudicots remain unresolved. Direct comparisons of analytic results from several data partitions with or without RNA editing sites show that in multigene analyses, RNA editing has no effect on well supported rela- tionships, but minor effect on weakly supported ones. Finally, comparisons of results from separate analyses of mitochondrial and chloroplast genes demonstrate that mitochondrial genes, with overall slower rates of sub- stitution than chloroplast genes, are informative phylogenetic markers, and are particularly suitable for resolv- ing deep relationships. -

World Heritage Values and to Identify New Values

FLORISTIC VALUES OF THE TASMANIAN WILDERNESS WORLD HERITAGE AREA J. Balmer, J. Whinam, J. Kelman, J.B. Kirkpatrick & E. Lazarus Nature Conservation Branch Report October 2004 This report was prepared under the direction of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment (World Heritage Area Vegetation Program). Commonwealth Government funds were contributed to the project through the World Heritage Area program. The views and opinions expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment or those of the Department of the Environment and Heritage. ISSN 1441–0680 Copyright 2003 Crown in right of State of Tasmania Apart from fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any means without permission from the Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment. Published by Nature Conservation Branch Department of Primary Industries, Water and Environment GPO Box 44 Hobart Tasmania, 7001 Front Cover Photograph: Alpine bolster heath (1050 metres) at Mt Anne. Stunted Nothofagus cunninghamii is shrouded in mist with Richea pandanifolia scattered throughout and Astelia alpina in the foreground. Photograph taken by Grant Dixon Back Cover Photograph: Nothofagus gunnii leaf with fossil imprint in deposits dating from 35-40 million years ago: Photograph taken by Greg Jordan Cite as: Balmer J., Whinam J., Kelman J., Kirkpatrick J.B. & Lazarus E. (2004) A review of the floristic values of the Tasmanian Wilderness World Heritage Area. Nature Conservation Report 2004/3. Department of Primary Industries Water and Environment, Tasmania, Australia T ABLE OF C ONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS .................................................................................................................................................................................1 1. -

Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed Port Kembla Bulk Liquids Terminal

Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed Port Kembla Bulk Liquids Terminal + Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed Port Kembla Bulk Liquids Terminal TQ Reference: PJ-PK-0001-REPT-017 82015103-001/Report 002 Ver 5 Prepared for TQ Holdings Australia Pty Ltd 4 December 2015 Cardno ref: 82015103-001/Report 002 Ver 5 December 2015 i Ecological Impact Assessment Proposed Port Kembla Bulk Liquids Terminal Contact Information Document Information Cardno South Coast Prepared for TQ Holdings Australia Trading as Cardno (NSW/ACT) Pty Ltd Pty Ltd ABN 95 001 145 035 Project Name Proposed Port Kembla Bulk Liquids Terminal Level 1, 47 Burelli Street File Reference Report 002 Ver 5 - PO Box 1285 Ecology - TQ Bulk Wollongong NSW 2500 Fuels (Final TQ Issue).docx Telephone: 02 4228 4133 Facsimile: 02 4228 6811 TQ Reference PJ-PK-0001-REPT-017 International: +61 2 4228 4133 Job Reference 82015103-001/Report 002 Ver 5 [email protected] Date 4 December 2015 www.cardno.com.au Version Number Ver 5 Author(s): Cassy Baxter Lucas McKinnon Environmental Scientist Terrestrial Ecologist Effective Date 4 December 2015 (Cardno) (Ecoplanning) Lachlan Barnes Environmental Scientist (Cardno) Date Approved: 4 December 2015 Approved By: Peggy O’Donnell Practice Lead Ecology (Cardno) Document History Version Effective Description of Revision Prepared by: Reviewed by: Date 4 30/09/2015 Final Report to Client CNB POD 5 4/12/2015 Update from NSW Ports and client CNB AJL/lLM comments and to include ref to expert report © Cardno. Copyright in the whole and every part of this document belongs to Cardno and may not be used, sold, transferred, copied or reproduced in whole or in part in any manner or form or in or on any media to any person other than by agreement with Cardno. -

Tourism Opportunities Plan Report Prepared for Kiama Municipal Council July 2018

Tourism Opportunities Plan Report Prepared for Kiama Municipal Council July 2018 1 Kiama Tourism Opportunities Plan – Report Table of Contents Introduction ...................................................................................................................................................... 10 Methodology ................................................................................................................................................ 12 Product and Market Review ....................................................................................................................... 14 Tourism Market Review ............................................................................................................................. 15 Product and Experience Review ............................................................................................................. 17 Defining Kiama’s Hero Experiences ....................................................................................................... 19 Hero Experiences....................................................................................................................................... 20 Tourism Development and Investment Opportunities ..................................................................... 23 Long List of Development Opportunities ................................................................................................. 24 Project Prioritisation ...................................................................................................................................... -

Flora Surveys Introduction Survey Method Results

Hamish Saunders Memorial Island Survey Program 2009 45 Flora Surveys The most studied island is Sarah Results Island. This island has had several Introduction plans developed that have A total of 122 vascular flora included flora surveys but have species from 56 families were There have been few flora focused on the historical value of recorded across the islands surveys undertaken in the the island. The NVA holds some surveyed. The species are Macquarie Harbour area. Data on observations but the species list comprised of 50 higher plants the Natural Values Atlas (NVA) is not as comprehensive as that (7 monocots and 44 dicots) shows that observations for given in the plans. The Sarah and 13 lower plants. Of the this area are sourced from the Island Visitor Services Site Plan species recorded 14 are endemic Herbarium, projects undertaken (2006) cites a survey undertaken to Australia; 1 occurs only in by DPIPWE (or its predecessors) by Walsh (1992). The species Tasmania. Eighteen species are such as the Huon Pine Survey recorded for Sarah Island have considered to be primitive. There and the Millennium Seed Bank been added to some of the tables were 24 introduced species found Collection project. Other data in this report. with 9 of these being listed weeds. has been added to the NVA as One orchid species was found part of composite data sets such Survey Method that was not known to occur in as Tasforhab and wetforest data the south west of the state and the sources of which are not Botanical surveys were this discovery has considerably easily traceable. -

NF5 Agenda 4 March 2020.Pdf

Neighbourhood Coniston, Figtree, Gwynneville, Keiraville, Forum 5 Mangerton, Mount Keira, Mount St Thomas, North Wollongong’s Wollongong, West Heartland Wollongong, Wollongong City. Agenda for meeting at 7.00 pm Wed 4th March 2020 in the Town Hall Ocean Room 1 Presentation Chris Stewart, WCC Manager City Strategy on the City Centre Review 2 Apologies 3 Minutes of meeting of 5th February and matters arising; see pp 12-15. 4 Comments 4.1 Councillors; 4.2 Council staff - Mark Roebuck on emergency management; 4.2 Residents; 4.3 University. 5 Responses 5.1 Neighbourhood Forums' workshop see p. 2 and p. 9 5.2 Traffic Signal Timing: see p.2 and p. 10 5.3 Development up the Escarpment: see p.2 and p. 10 5.4 Trains: see p.3 6 Reports 6.1 Bird Strikes: see rec p.3 6.2 Conditions of Consent for Park Events: see p.3 & rec p.4 6.3 New Parks for Major Events: see rec p.4 6.4 Community Engagement: see rec p.4 6.5 University: see p.5 7 Key Issues 7.1 City Centre: see p.5 & rec p.4 7.2 High Rise Residential: see p.6 7.3 Medium Density development: see p.6 7.4 Keiraville-Gwynneville: see p.6 7.5 South Wollongong: see p.6 7.6 Escarpment; see p.6 8 Planning DAs: see rec p. 7 9 General Business: 10 Snippets see p. 8 Next Meeting (AGM): 7.00 pm on Wed. 1st April 2020, Town Hall Ocean Room. Current active membership of Neighbourhood Forum 5 : 402 households 1 5 Responses 5.1 Neighbourhood Forums' workshop Given that 3 of 8 original Forums are defunct there needed to be an urgent review of the way Council promotes, supports and demonstrates the legitimacy of the Forums, Council was requested to organise a workshop with representatives from the existing Forums, Engagement staff and those Councillors who consistently support their Forums. -

No. 119 JUNE 2004 Price: $5.00 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 119 (June 2004)

No. 119 JUNE 2004 Price: $5.00 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 119 (June 2004) AUSTRALIAN SYSTEMATIC BOTANY SOCIETY INCORPORATED Council President Vice President Stephen Hopper John Clarkson School of Plant Biology Centre for Tropical Agriculture University of Western Australia PO Box 1054 CRAWLEY WA 6009 MAREEBA, Queensland 4880 tel: (08) 6488 1647 tel: (07) 4048 4745 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Secretary Treasurer Brendan Lepschi Anthony Whalen Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Australian National Herbarium Australian National Herbarium GPO Box 1600 GPO Box 1600 CANBERRA ACT 2601 CANBERRA ACT 2601 tel: (02) 6246 5167 tel: (02) 6246 5175 email: [email protected] email: [email protected] Councillor Councillor Darren Crayn Marco Duretto Royal Botanic Gardens Sydney Tasmanian Herbarium Mrs Macquaries Road Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery SYDNEY NSW 2000 Private Bag 4 tel: (02) 9231 8111 HOBART , Tasmania 7001 email: [email protected] tel.: (03) 6226 1806 ema il: [email protected] Other Constitutional Bodies Public Officer Hansjörg Eichler Research Committee Kirsten Cowley Barbara Briggs Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Rod Henderson Australian National Herbarium Betsy Jackes GPO Box 1600, CANBERRA ACT 2601 Tom May tel: (02) 6246 5024 Chris Quinn email: [email protected] Chair: Vice President (ex officio) Affiliate Society Papua New Guinea Botanical Society ASBS Web site www.anbg.gov.au/asbs Webmaster: Murray Fagg Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research Australian National Herbarium Email: [email protected] Loose-leaf inclusions with this issue · CSIRO Publishing publications pamphlet Publication dates of previous issue Austral.Syst.Bot.Soc.Nsltr 118 (March 2004 issue) Hardcopy: 28th April 2004; ASBS Web site: 4th May 2004 Australian Systematic Botany Society Newsletter 119 (June 2004) ASBS Inc.