Report Structure

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cone Collector N°23

THE CONE COLLECTOR #23 October 2013 THE Note from CONE the Editor COLLECTOR Dear friends, Editor The Cone scene is moving fast, with new papers being pub- António Monteiro lished on a regular basis, many of them containing descrip- tions of new species or studies of complex groups of species that Layout have baffled us for many years. A couple of books are also in André Poremski the making and they should prove of great interest to anyone Contributors interested in Cones. David P. Berschauer Pierre Escoubas Our bulletin aims at keeping everybody informed of the latest William J. Fenzan developments in the area, keeping a record of newly published R. Michael Filmer taxa and presenting our readers a wide range of articles with Michel Jolivet much and often exciting information. As always, I thank our Bernardino Monteiro many friends who contribute with texts, photos, information, Leo G. Ros comments, etc., helping us to make each new number so inter- Benito José Muñoz Sánchez David Touitou esting and valuable. Allan Vargas Jordy Wendriks The 3rd International Cone Meeting is also on the move. Do Alessandro Zanzi remember to mark it in your diaries for September 2014 (defi- nite date still to be announced) and to plan your trip to Ma- drid. This new event will undoubtedly be a huge success, just like the two former meetings in Stuttgart and La Rochelle. You will enjoy it and of course your presence is indispensable! For now, enjoy the new issue of TCC and be sure to let us have your opinions, views, comments, criticism… and even praise, if you feel so inclined. -

Population and Housing Census 2014

MALDIVES POPULATION AND HOUSING CENSUS 2014 National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’, Maldives 4 Population & Households: CENSUS 2014 © National Bureau of Statistics, 2015 Maldives - Population and Housing Census 2014 All rights of this work are reserved. No part may be printed or published without prior written permission from the publisher. Short excerpts from the publication may be reproduced for the purpose of research or review provided due acknowledgment is made. Published by: National Bureau of Statistics Ministry of Finance and Treasury Male’ 20379 Republic of Maldives Tel: 334 9 200 / 33 9 473 / 334 9 474 Fax: 332 7 351 e-mail: [email protected] www.statisticsmaldives.gov.mv Cover and Layout design by: Aminath Mushfiqa Ibrahim Cover Photo Credits: UNFPA MALDIVES Printed by: National Bureau of Statistics Male’, Republic of Maldives National Bureau of Statistics 5 FOREWORD The Population and Housing Census of Maldives is the largest national statistical exercise and provide the most comprehensive source of information on population and households. Maldives has been conducting censuses since 1911 with the first modern census conducted in 1977. Censuses were conducted every five years since between 1985 and 2000. The 2005 census was delayed to 2006 due to tsunami of 2004, leaving a gap of 8 years between the last two censuses. The 2014 marks the 29th census conducted in the Maldives. Census provides a benchmark data for all demographic, economic and social statistics in the country to the smallest geographic level. Such information is vital for planning and evidence based decision-making. Census also provides a rich source of data for monitoring national and international development goals and initiatives. -

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda)1

The Hawaiian Species of Conus (Mollusca: Gastropoda) 1 ALAN J. KOHN2 IN THECOURSE OF a comparative ecological currents are factors which could plausibly study of gastropod mollus ks of the genus effect the isolation necessary for geographic Conus in Hawaii (Ko hn, 1959), some 2,400 speciation . specimens of 25 species were examined. Un Of the 33 species of Conus considered in certainty ofthe correct names to be applied to this paper to be valid constituents of the some of these species prompted the taxo Hawaiian fauna, about 20 occur in shallow nomic study reported here. Many workers water on marine benches and coral reefs and have contributed to the systematics of the in bays. Of these, only one species, C. ab genus Conus; nevertheless, both nomencla breviatusReeve, is considered to be endemic to torial and biological questions have persisted the Hawaiian archipelago . Less is known of concerning the correct names of a number of the species more characteristic of deeper water species that occur in the Hawaiian archi habitats. Some, known at present only from pelago, here considered to extend from Kure dredging? about the Hawaiian Islands, may (Ocean) Island (28.25° N. , 178.26° W.) to the in the future prove to occur elsewhere as island of Hawaii (20.00° N. , 155.30° W.). well, when adequate sampling methods are extended to other parts of the Indo-West FAUNAL AFFINITY Pacific region. As is characteristic of the marine fauna of ECOLOGY the Hawaiian Islands, the affinities of Conus are with the Indo-Pacific center of distribu Since the ecology of Conus has been dis tion . -

View Brochure

HIGH ENERGY DEEP IMMERSION Explore Group Adventures in the Maldives > DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT Beyond the Beaches The Maldives isn’t just for honeymooners. Or couples. Or beach-lovers. Or divers. Venture beyond the pearly whites and Tiffany blues of the world’s most aquatic nation and you’ll discover an archipelago that’s alive with culture and conservation, innovation and ingenuity. In a country of 1,192 low-lying islands strung across 90,000 square kilometres of the Indian Ocean, Four Seasons offers four distinctive properties that venture beyond the beaches to bring you more of the Maldives. Discover the Collection > DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT The Maldives Collection Discover the quintessential Maldivian quartet with Four Seasons Resort Four Seasons. Embark on a journey of wild UNESCO Four Seasons Resort Maldives at Kuda Huraa > Maldives at Landaa Giraavaru > discovery at Landaa Giraavaru; encounter a welcoming garden village at Kuda Huraa; explore undiscovered worlds Four Seasons Private Island Maldives at Voavah, Baa Atoll > above and below onboard Four Seasons Explorer; and play Four Seasons Explorer > with your own limitless potential at Voavah Private Island. DESTINATION THE COLLECTION PLAY EAT STAY RELAX CONNECT KUDA HURAA Feel the Magic Kuda Huraa isn’t a place, it’s a feeling: of warmth, comfort and naturalness. Charming and intimate, this enchanting garden island embraces guests with an almost familial devotion. A shared haven for water-lovers – from tiny turtles to surfing’s biggest names – Kuda Huraa is the ear-to-ear smile of catching your first wave, the spray-in-your-face joy of sailing alongside spinner dolphins, and the toes-in-the-sand rhythm of learning to beat a bodu beru drum. -

Dicembre 2010

PRO NATURA NOVARA ONLUS GRUPPO MALACOLOGICO NOVARESE Gianfranco Vischi ([email protected]) n- 9 - Dicembre 2010 LA CONCHIGLIA CHIMERA CHIMAERIA INCOMPARABILIS ( Falsa Cypraea? Rarissimo Ovulide? Fossile vivente?) a cura di Paolo Cesana In biologia, Chimera è un organismo che ''ha caratteri di molti altri'' (vedi nella mitologia il favoloso essere mostruoso. Le prime notizie della Chimera sono nel libro dell' Iliade). Qui di mostruoso non vi è nulla, ma anzi di meraviglioso, di una bellezza che abbaglia gli occhi (del malacologo e non). Parliamo della stupenda quanto misteriosa,enigmatica e rarissima CHIMAERIA INCOMPARABILIS (la Chimera incomparabile - BRIANO B. 1993). Chimera è il nome appropriato, perché questa splendida conchiglia (se ne conoscono, dati al 2009 solo 6 esemplari nelle collezioni di tutto il mondo) è un po’ un enigma per gli studiosi, chi la classifica nella grande Famiglia delle Cypraee - eocypraeinae - sottofam. Cypraeovulinae ? Chi nella Fam. Ovulidae - ovulinae. Anche il genere è contrastato, alcuni la classificano col genere SPHAEROCYPRAEA (con specie fossili molto simili l'attuale, risalenti all' Eocene, vedi fig. allegata ). EOCYPRAEIDAE è una piccola famiglia di Sphaerocypraea tardivelae grandi lumache di mare, consiste come detto principalmente di specie fossili (dall' Eocene inf. circa 55 milioni di anni) fino ai giorni nostri, vedere schema illustrativo. Qualche altro afferma che la conchiglia in questione possa appartenere a un gruppo a sé stante. VENIAMO ALLA DESCRIZIONE: La Chimaeria incomparabilis (o Sphaerocypraea) -

Register 2010-2019

Impressum Verantwortlich i.S.d.P.: Dr. MANFRED HERRMANN, Rosdorf und die Redaktion Herausgegeben vom Club Conchylia e.V., Öhringen, Deutschland Vorstand des Club Conchylia: 1. Vorsitzender 2. Vorsitzender Schatzmeister Dr. MANFRED HERRMANN, Ulmenstrasse 14 ROLAND GÜNTHER, Blücherstrasse 15 STEFFEN FRANKE, Geistenstraße 24 D-37124 Rosdorf D-40477 Düsseldorf D-40476 Düsseldorf Tel.: 0049-(0)551-72055; Fax. -72099 Tel.: 0049-(0)211-6007827 Tel 0049-(0)211 - 514 20 81 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Regionale Vorstände: Norddeutschland: Westdeutschland: Süddeutschland: Dr. VOLLRATH WIESE, Hinter dem Kloster 42 kommissarisch durch den 2. Vorsitzenden INGO KURTZ, Prof.-Kneib-Str. 10 D-23743 Cismar ROLAND GÜNTHER (siehe oben) D-55270 Zornheim Tel. / Fax: 0049-(0 )4366-1288 Tel.: 0049-(0)6136-758750 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Ostdeutschland: Schweiz: PEER SCHEPANSKI, Am Grünen Hang 23 FRANZ GIOVANOLI, Gstaadmattstr. 13 D-09577 Niederwiesa CH-4452 Itingen Tel.: 0049 (0)1577-517 44 03 Tel.: 0041- 61- 971 15 48 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Redaktion Conchylia + Acta Conchyliorum: Redaktion Club Conchylia Mitteilungen: KLAUS GROH ROLAND HOFFMANN Hinterbergstr. 15 Eichkoppelweg 14a D-67098 Bad Dürkheim D-24119 Kronshagen Tel.: 0049-(0)6322-988 70 68 Tel.: 0049-(0)431-583 68 81 E-Mail: [email protected] E-Mail: [email protected] Bank-Konto des Club Conchylia e.V.: Volksbank Mitte eG, Konto Nr. : 502 277 00, Bankleitzahl: 260 612 91; Intern. Bank-Acc.-Nr (IBAN): DE77 2606 1291 0050 2277 00 Bank Identifier Code (BIC): GENODEF1DUD; Club-home-page: www.club-conchylia.de (Dr. -

Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/274311543 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis · April 2004 CITATIONS READS 0 100 1 author: Benjamin Vallejo University of the Philippines Diliman 28 PUBLICATIONS 88 CITATIONS SEE PROFILE Some of the authors of this publication are also working on these related projects: History of Philippine Science in the colonial period View project Available from: Benjamin Vallejo Retrieved on: 10 November 2016 Biogeography of Coral Reef Shore Gastropods in the Philippines Thesis submitted by Benjamin VALLEJO, JR, B.Sc (UPV, Philippines), M.Sc. (UPD, Philippines) in September 2003 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Marine Biology within the School of Marine Biology and Aquaculture James Cook University ABSTRACT The aim of this thesis is to describe the distribution of coral reef and shore gastropods in the Philippines, using the species rich taxa, Nerita, Clypeomorus, Muricidae, Littorinidae, Conus and Oliva. These taxa represent the major gastropod groups in the intertidal and shallow water ecosystems of the Philippines. This distribution is described with reference to the McManus (1985) basin isolation hypothesis of species diversity in Southeast Asia. I examine species-area relationships, range sizes and shapes, major ecological factors that may affect these relationships and ranges, and a phylogeny of one taxon. Range shape and orientation is largely determined by geography. Large ranges are typical of mid-intertidal herbivorous species. Triangualar shaped or narrow ranges are typical of carnivorous taxa. Narrow, overlapping distributions are more common in the central Philippines. The frequency of range sizesin the Philippines has the right skew typical of tropical high diversity systems. -

MINISTRY of TOURISM Approved Opening Dates of Tourist

MINISTRY OF TOURISM REPUBLIC OF MALDIVES Approved Opening dates of Tourist Resorts, Yacht Marinas, Tourist Hotels, Tourist Vessels, Tourist Guesthouses, Transit Facilities and Foreign Vessels (Updated on 14th March 2021) TOURIST RESORTS Opening Date No. of No. of No. Facility Name Atoll Island Approved by Beds Rooms MOT Four Seasons Private Island 1 Baa Voavah 26 11 In operation Maldives at Voavah Four Seasons Resort Maldives at 2 Baa Landaa Giraavaru 244 116 In operation Landaa Giraavaru Alifu 3 Lily Beach Resort Huvahendhoo 250 125 In operation Dhaalu 4 Lux North Male' Atoll Kaafu Olhahali 158 79 In operation 5 Oblu By Atmosphere at Helengeli Kaafu Helengeli 236 116 In operation 6 Soneva Fushi Resort Baa Kunfunadhoo 237 124 In operation 7 Varu Island Resort Kaafu Madivaru 244 122 In operation Angsana Resort & Spa Maldives – 8 Dhaalu Velavaru 238 119 In operation Velavaru 9 Velaa Private Island Maldives Noonu Fushivelaavaru 134 67 In operation 10 Cocoon Maldives Lhaviyani Ookolhu Finolhu 302 151 15-Jul-20 Four Seasons Resort Maldives at 11 Kaafu Kuda Huraa 220 110 15-Jul-20 Kuda Huraa 12 Furaveri Island Resort & Spa Raa Furaveri 214 107 15-Jul-20 13 Grand Park Kodhipparu Maldives Kaafu Kodhipparu 250 125 15-Jul-20 Island E -GPS coordinates: 14 Hard Rock Hotel Maldives Kaafu Latitude 4°7'24.65."N 396 198 15-Jul-20 Longitude 73°28'20.46"E 15 Kudafushi Resort & Spa Raa Kudafushi 214 107 15-Jul-20 Oblu Select by Atmosphere at 16 Kaafu Akirifushi 288 114 15-Jul-20 Sangeli 17 Sun Siyam Olhuveli Maldives Kaafu Olhuveli 654 327 15-Jul-20 18 -

THE LISTING of PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T

August 2017 Guido T. Poppe A LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS - V1.00 THE LISTING OF PHILIPPINE MARINE MOLLUSKS Guido T. Poppe INTRODUCTION The publication of Philippine Marine Mollusks, Volumes 1 to 4 has been a revelation to the conchological community. Apart from being the delight of collectors, the PMM started a new way of layout and publishing - followed today by many authors. Internet technology has allowed more than 50 experts worldwide to work on the collection that forms the base of the 4 PMM books. This expertise, together with modern means of identification has allowed a quality in determinations which is unique in books covering a geographical area. Our Volume 1 was published only 9 years ago: in 2008. Since that time “a lot” has changed. Finally, after almost two decades, the digital world has been embraced by the scientific community, and a new generation of young scientists appeared, well acquainted with text processors, internet communication and digital photographic skills. Museums all over the planet start putting the holotypes online – a still ongoing process – which saves taxonomists from huge confusion and “guessing” about how animals look like. Initiatives as Biodiversity Heritage Library made accessible huge libraries to many thousands of biologists who, without that, were not able to publish properly. The process of all these technological revolutions is ongoing and improves taxonomy and nomenclature in a way which is unprecedented. All this caused an acceleration in the nomenclatural field: both in quantity and in quality of expertise and fieldwork. The above changes are not without huge problematics. Many studies are carried out on the wide diversity of these problems and even books are written on the subject. -

CHICOREUS (NAQUETIA) TRIQUITER VOKESAE Sub.Nov

. APEX Vol. 1 (3), juillet 1986 - R. HOUART - CHICOREUS (NAQUETIA) TRIQUITER VOKESAE Sub.nov, NOV. CHICOREUS (NAQUETIA) TRIQUTTER VOKESAE SUBS. , A NEW NAME FOR A MISIDENTIFIED SPECIES GASTROPODA : MURICIDAE) Roland HOUART St. Jobsstraat, 8, B-3330 Landen (Ezemaal) Belgium. Scientific Collaborator at the Institut Royal des Sciences Naturelles de Belgique . Keywords : Gastropoda, Muricidae, Taxonomy. RESUME : L'espèce trouvée dans le Nord-Ouest de l'Océan Indien et généralement identifiée comme Chiooreus (Naquetia) triquiter (Born, 1778) est nommée ici comme sous-espèce nouvelle, sur base de différences conchyliologiques , surtout de la coquille larvaire. INTRODUCTION : The subgenus Naquetia was recently studied by the author (Houart, 1985). Further comparative study of the protoconchs lead to the discovery of an unidentified subspecies, occuring in the Western Indian Océan, which is hère named. Chiaoreus (Naquetia) triquiter vokesae subs.nov Figs. 1-2. DESCRIPTION : Shell medium-sized for the subgenus, to 70 mm. Elongate and fusiform. Aperture roundly ovate. Columellar lip adhèrent, briefly detached anteriorly, smooth. Anal notch small and shallow. Outer apertural lip slightly denticulate, briefly str ate interiorly. Spire high, consisting of two rounded, smooth nuclear whorls and nine elongate post- nuclear whorls. Suture impressed. Body whorl bearing three low rounded varices. Terminal varix ventrally squamous , ante- riorly ornamented with a varical f lange extending on the siphonal canal. Other axial sculpture consisting of three to five low ridges crossed by twelve to fifteen spiral cords, each flanked by fine spiral threads. Varices of spire whorls sometimes bearing small carinal open spines. Siphonal canal short and broad, narrowly open and slightly bent backwards. Color cream to light brown with darker spiral bahds . -

CONE SHELLS - CONIDAE MNHN Koumac 2018

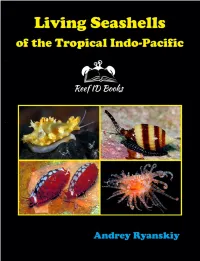

Living Seashells of the Tropical Indo-Pacific Photographic guide with 1500+ species covered Andrey Ryanskiy INTRODUCTION, COPYRIGHT, ACKNOWLEDGMENTS INTRODUCTION Seashell or sea shells are the hard exoskeleton of mollusks such as snails, clams, chitons. For most people, acquaintance with mollusks began with empty shells. These shells often delight the eye with a variety of shapes and colors. Conchology studies the mollusk shells and this science dates back to the 17th century. However, modern science - malacology is the study of mollusks as whole organisms. Today more and more people are interacting with ocean - divers, snorkelers, beach goers - all of them often find in the seas not empty shells, but live mollusks - living shells, whose appearance is significantly different from museum specimens. This book serves as a tool for identifying such animals. The book covers the region from the Red Sea to Hawaii, Marshall Islands and Guam. Inside the book: • Photographs of 1500+ species, including one hundred cowries (Cypraeidae) and more than one hundred twenty allied cowries (Ovulidae) of the region; • Live photo of hundreds of species have never before appeared in field guides or popular books; • Convenient pictorial guide at the beginning and index at the end of the book ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The significant part of photographs in this book were made by Jeanette Johnson and Scott Johnson during the decades of diving and exploring the beautiful reefs of Indo-Pacific from Indonesia and Philippines to Hawaii and Solomons. They provided to readers not only the great photos but also in-depth knowledge of the fascinating world of living seashells. Sincere thanks to Philippe Bouchet, National Museum of Natural History (Paris), for inviting the author to participate in the La Planete Revisitee expedition program and permission to use some of the NMNH photos. -

Maldives Map 2012

MAP OF MALDIVES Thuraakunu Van ’gaa ru Uligamu Innafinolhu Madulu Thiladhunmathee Uthuruburi Berinmadhoo Gaamathikulhudhoo (Haa Alifu Atoll) Matheerah Hathifushi Govvaafushi Umarefinolhu Medhafushi Mulhadhoo Maafinolhu Velifinolhu Manafaru (The Beach House at Manafaru Maldives) Kudafinolhu Huvarafushi Un’gulifinolhu Huvahandhoo Kelaa Ihavandhoo Gallandhoo Beenaafushi Kan’daalifinolhu Dhigufaruhuraa Dhapparuhuraa Dhidhdhoo Vashafaru Naridhoo Filladhoo Maarandhoo Alidhuffarufinolhu Thakandhoo Gaafushi Alidhoo (Cinnamon Island Alidhoo) Utheemu Muraidhoo UPPER NORTH PROVINCE Mulidhoo Dhonakulhi Maarandhoofarufinolhu Maafahi Baarah Faridhoo Hon’daafushi Hon’daidhoo Veligan’du Ruffushi Hanimaadhoo Naivaadhoo Finey Theefaridhoo Hirimaradhoo Kudafarufasgandu Nellaidhoo Kanamana Hirinaidhoo Nolhivaranfaru Huraa Naagoashi Kurin’bee Muiri Nolhivaramu Kun’burudhoo Kudamuraidhoo Kulhudhuffushi Keylakunu Thiladhunmathee Dhekunuburi Kattalafushi Kumundhoo Vaikaradhoo (Haa Dhaalu Atoll) Vaikaramuraidhoo Neykurendhoo Maavaidhoo Kakaa eriyadhoo Gonaafarufinolhu Neyo Kan’ditheemu Kudadhoo Goidhoo Noomaraa Miladhunmadulu Uthuruburi (Shaviyani Atoll) Innafushi Makunudhoo Fenboahuraa Fushifaru Feydhoo Feevah Bileiyfahi Foakaidhoo Nalandhoo Dhipparufushi Madidhoo Madikuredhdhoo Gaakoshibi Milandhoo Narurin’budhoo Narudhoo Maakan’doodhoo Migoodhoo Maroshi Naainfarufinolhu Farukolhu Medhukun’burudhoo Hirubadhoo Dhonvelihuraa Lhaimagu Bis alhaahuraa Hurasfaruhuraa Funadhoo Naalaahuraa Kan’baalifaru Raggan’duhuraa Firun’baidhoo Eriadhoo Van’garu (Maakanaa) Boduhuraa