Root Rot Mary Olsen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Basic Soil Science W

Basic Soil Science W. Lee Daniels See http://pubs.ext.vt.edu/430/430-350/430-350_pdf.pdf for more information on basic soils! [email protected]; 540-231-7175 http://www.cses.vt.edu/revegetation/ Well weathered A Horizon -- Topsoil (red, clayey) soil from the Piedmont of Virginia. This soil has formed from B Horizon - Subsoil long term weathering of granite into soil like materials. C Horizon (deeper) Native Forest Soil Leaf litter and roots (> 5 T/Ac/year are “bio- processed” to form humus, which is the dark black material seen in this topsoil layer. In the process, nutrients and energy are released to plant uptake and the higher food chain. These are the “natural soil cycles” that we attempt to manage today. Soil Profiles Soil profiles are two-dimensional slices or exposures of soils like we can view from a road cut or a soil pit. Soil profiles reveal soil horizons, which are fundamental genetic layers, weathered into underlying parent materials, in response to leaching and organic matter decomposition. Fig. 1.12 -- Soils develop horizons due to the combined process of (1) organic matter deposition and decomposition and (2) illuviation of clays, oxides and other mobile compounds downward with the wetting front. In moist environments (e.g. Virginia) free salts (Cl and SO4 ) are leached completely out of the profile, but they accumulate in desert soils. Master Horizons O A • O horizon E • A horizon • E horizon B • B horizon • C horizon C • R horizon R Master Horizons • O horizon o predominantly organic matter (litter and humus) • A horizon o organic carbon accumulation, some removal of clay • E horizon o zone of maximum removal (loss of OC, Fe, Mn, Al, clay…) • B horizon o forms below O, A, and E horizons o zone of maximum accumulation (clay, Fe, Al, CaC03, salts…) o most developed part of subsoil (structure, texture, color) o < 50% rock structure or thin bedding from water deposition Master Horizons • C horizon o little or no pedogenic alteration o unconsolidated parent material or soft bedrock o < 50% soil structure • R horizon o hard, continuous bedrock A vs. -

A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible Through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application

agronomy Article A Sustainable Approach for Improving Soil Properties and Reducing N2O Emissions Is Possible through Initial and Repeated Biochar Application Ján Horák 1,* , Tatijana Kotuš 1, Lucia Toková 1, Elena Aydın 1 , Dušan Igaz 1 and Vladimír Šimanský 2 1 Department of Biometeorology and Hydrology, Faculty of Horticulture and Landscape Engineering, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] (T.K.); [email protected] (L.T.); [email protected] (E.A.); [email protected] (D.I.) 2 Department of Soil Science, Faculty of Agrobiology and Food Resources, Slovak University of Agriculture, 949 76 Nitra, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Recent findings of changing climate, water scarcity, soil degradation, and greenhouse gas emissions have brought major challenges to sustainable agriculture worldwide. Biochar application to soil proves to be a suitable solution to these problems. Although the literature presents the pros and cons of biochar application, very little information is available on the impact of repeated application. In this study, we evaluate and discuss the effects of initial and reapplied biochar (both in rates of 0, 10, and 20 t ha−1) combined with N fertilization (at doses of 0, 40, and 80 kg ha−1) on soil properties and N O emission from Haplic Luvisol in the temperate climate zone (Slovakia). Results showed that 2 biochar generally improved the soil properties such as soil pH(KCl) (p ≤ 0.05; from acidic towards Citation: Horák, J.; Kotuš, T.; Toková, moderately acidic), soil organic carbon (p ≤ 0.05; an increase from 4% to over 100%), soil water L.; Aydın, E.; Igaz, D.; Šimanský, V. -

Summary a Plant Is an Integrated System Which: 1

Summary A plant is an integrated system which: 1. Obtains water and nutrients from the soil. 2. Transports them 3. Combines the H2O with CO2 to make sugar. 4. Exports sugar to where it’s needed Today, we’ll start to go over how this occurs Transport in Plants – Outline I.I. PlantPlant waterwater needsneeds II.II. TransportTransport ofof waterwater andand mineralsminerals A.A. FromFrom SoilSoil intointo RootsRoots B.B. FromFrom RootsRoots toto leavesleaves C.C. StomataStomata andand transpirationtranspiration WhyWhy dodo plantsplants needneed soso muchmuch water?water? TheThe importanceimportance ofof waterwater potential,potential, pressure,pressure, solutessolutes andand osmosisosmosis inin movingmoving water…water… Transport in Plants 1.1. AnimalsAnimals havehave circulatorycirculatory systems.systems. 2.2. VascularVascular plantsplants havehave oneone wayway systems.systems. Transport in Plants •• OneOne wayway systems:systems: plantsplants needneed aa lotlot moremore waterwater thanthan samesame sizedsized animals.animals. •• AA sunflowersunflower plantplant “drinks”“drinks” andand “perspires”“perspires” 1717 timestimes asas muchmuch asas aa human,human, perper unitunit ofof mass.mass. Transport of water and minerals in Plants WaterWater isis goodgood forfor plants:plants: 1.1. UsedUsed withwith CO2CO2 inin photosynthesisphotosynthesis toto makemake “food”.“food”. 2.2. TheThe “blood”“blood” ofof plantsplants –– circulationcirculation (used(used toto movemove stuffstuff around).around). 3.3. EvaporativeEvaporative coolingcooling. -

Some Biochemical Aspects of Vascular Wilts*

SOME BIOCHEMICAL ASPECTS OF VASCULAR WILTS* BY K. LAKSHMINAKAYANAN (University Botany Laboratory, Madras-5) TOXIN : GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS [N recent years considerable attention has been directed towards the study of microbial metabolic products by a number of workers in different countries (Raistrick, Arnstein and Cook in England, Gaumann and his school of workers in Switzerland, Dimond, Waggoner, Scheffer and Walker in the States) in view of their complicity in the production of many diseases by pathogens. They have been loosely called as toxins. The term toxin has been applied with so many different meanings in different contexts that it has become difficult to define it in precise terms. In therapeutics, the term is used to denote specific organic nitrogenous compounds produced by bacteria, in such diseases as tetanus, gas gangrene, diphtheria, etc. The term ' Wilting Toxin' was first applied by G~tumann (1950, 1951) to denote toxic metaoblites of fungal origin as enniatins, lycomarasmine, javanicin, etc., that were toxic to higher plants and claimed to be the primary cause of some or other of the syndrome of wilts. Vascular wilts were thus classified under toxigenic wilting. Toxins were claimed to be synthesized by the parasites (fungi or bacteria) as regular metabolic products in the course of their normal activity enter into the vascular system of the host plants and carried to the different part s of the plants wherein they initiate the various symptoms observed in the different organs. Dimond and Waggoner (1953 b) suggested a new term 'vivotoxin' defined as 'a substance produced in the infected host by the pathogen and/or its host which functions in the production of the disease but is not itself the initial inciting agent'. -

L723 Wilt, Nematode, and Virus Diseases of Tomato

Wilt, Nematode, and Virus Diseases of Tomato Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station and Cooperative Extension Service Tomatoes are susceptible to numerous diseases. This publication addresses wilt, nematode, and virus diseases. For descriptions of leaf or fruit spotting diseases, see K-State Research and Extension publication Leaf and Fruit Diseases of Tomato, L721. Fusarium and Verticillium wilt Two major wilt diseases of tomatoes are Fusarium and Verticillium wilt. These wilt-causing fungi live in the soil and enter the plants through the roots. Once inside the plant, they enter the water-conducting tissues and block the water supply. Plants are deprived of water and show wilt symptoms, especially during dry conditions. Symptoms Fusarium wilt, the more prevalent of the two diseases in Kansas, generally occurs in midsummer when air and soil temperatures are high. Diseased plants develop a yellow- ing of the oldest leaves (those near the ground). Often the yellowing is restricted to one side of the plant or to leaflets on one side of the petiole (the stalk that joins the leaf and stem). The affected leaves soon wilt and dry up, but they Figure 2. Vascular browning associated with Fusarium wilt. remain attached to the plant. The wilting continues on suc- (photo courtesy of Clemson University, USDA Cooperative Extension cessively younger foliage and eventually results in the death Slide Series, www.ipmimages.org) of the plant (Figure 1). The stem remains firm and green on the outside, but exhibits a narrow band of brown discolor- between the central pith region and the outer portion of ation (streaking) in the vascular tissue. -

Transport of Water and Solutes in Plants

Transport of Water and Solutes in Plants Water and Solute Potential Water potential is the measure of potential energy in water and drives the movement of water through plants. LEARNING OBJECTIVES Describe the water and solute potential in plants Key Points Plants use water potential to transport water to the leaves so that photosynthesis can take place. Water potential is a measure of the potential energy in water as well as the difference between the potential in a given water sample and pure water. Water potential is represented by the equation Ψsystem = Ψtotal = Ψs + Ψp + Ψg + Ψm. Water always moves from the system with a higher water potential to the system with a lower water potential. Solute potential (Ψs) decreases with increasing solute concentration; a decrease in Ψs causes a decrease in the total water potential. The internal water potential of a plant cell is more negative than pure water; this causes water to move from the soil into plant roots via osmosis.. Key Terms solute potential: (osmotic potential) pressure which needs to be applied to a solution to prevent the inward flow of water across a semipermeable membrane transpiration: the loss of water by evaporation in terrestrial plants, especially through the stomata; accompanied by a corresponding uptake from the roots water potential: the potential energy of water per unit volume; designated by ψ Water Potential Plants are phenomenal hydraulic engineers. Using only the basic laws of physics and the simple manipulation of potential energy, plants can move water to the top of a 116-meter-tall tree. Plants can also use hydraulics to generate enough force to split rocks and buckle sidewalks. -

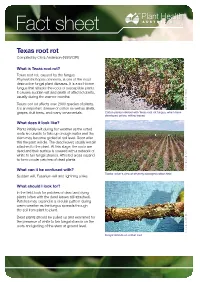

Texas Root Rot Compiled by Chris Anderson (NSW DPI)

Fact sheet Texas root rot Compiled by Chris Anderson (NSW DPI) What is Texas root rot? Texas root rot, caused by the fungus Phymatotrichopsis omnivora, is one of the most destructive fungal plant diseases. It is a soil-borne fungus that attacks the roots of susceptible plants. It causes sudden wilt and death of affected plants, usually during the warmer months. Texas root rot affects over 2000 species of plants. It is an important disease of cotton as well as alfalfa, Chris Anderson, I&I NSW grapes, fruit trees, and many ornamentals. Cotton plants infected with Texas root rot fungus, which have developed yellow, wilting leaves What does it look like? Plants initially wilt during hot weather as the rotted roots are unable to take up enough water and the stem may become girdled at soil level. Soon after this the plant will die. The dead leaves usually remain attached to the plant. At this stage, the roots are dead and their surface is covered with a network of white to tan fungal strands. Affected areas expand to form circular patches of dead plants. What can it be confused with? Chris Anderson, I&I NSW Tractor driver’s view of severely damaged cotton field Sudden wilt, Fusarium wilt and lightning strike. What should I look for? In the field, look for patches of dead and dying plants (often with the dead leaves still attached). Patches may expand in a circular pattern during warm weather as the fungus spreads through the soil from plant to plant. Dead plants should be pulled up and examined for the presence of white to tan fungal strands on the roots and girdling of the stem at ground level. -

Soil Moisture Extraction and Physiological Wilting of Cotton on Mississippi River Alluvial Soils K N

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports LSU AgCenter 1965 Soil moisture extraction and physiological wilting of cotton on Mississippi River alluvial soils K N. Clower Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/agexp Recommended Citation Clower, K N., "Soil moisture extraction and physiological wilting of cotton on Mississippi River alluvial soils" (1965). LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports. 713. http://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/agexp/713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the LSU AgCenter at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Agricultural Experiment Station Reports by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. (»7 Bulletin No. 598 K. N. GLOWER W.H. PATRICK, JR. Soil Moisture Extraction and hiysiological IVilting of Cotton on {Mississippi River Alluvial Soils Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College Agricultural Experiment Station Doyle Chambers, Director Contents Page Abstract ^ Introduction ^ Materials and Methods ^ Results and Discussion 4 Preliminary Survey of Available Soil Moisture 4 Moisture Extraction Pattern in Dundee Loam at Barcelona Plantation 8 Moisture Extraction Pattern in Dundee Loam at Midway Plantation 11 Moisture Extraction Pattern in Commerce Fine Sandy Loam on the "Island" 14 Soil Physical Properties 15 Summary and Conclusions 21 Literature Cited 22 Soil Moisture Extraction and Physiological Wilting of Cotton on Mississippi River Alluvial Soils K. N. Glower and W. H. Patrick, Jr/ Abstract Physiological wilting of cotton on the Mississippi River floodplain soils of Northeast Louisiana was found to occur because of a shortage of available moisture at the beginning of the growing season. -

Why Do Plants Wilt? Investigating Students' Understanding of Water

EURASIA Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education, 2018, 14(6), 2265-2276 ISSN:1305-8223 (online) 1305-8215 (print) OPEN ACCESS Research Paper https://doi.org/10.29333/ejmste/87119 Why do Plants Wilt? Investigating Students’ Understanding of Water Balance in Plants with External Representations at the Macroscopic and Submicroscopic Levels Gregor Torkar 1, Manja Veldin 2, Saša Aleksej Glažar 1, Anja Podlesek 3* 1 University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Education, Department of Biology, Chemistry and Home Economics, Ljubljana, SLOVENIA 2 The Educational Research Institute, Ljubljana, SLOVENIA 3 University of Ljubljana, Faculty of Arts, Department of Psychology, Ljubljana, SLOVENIA Received 20 December 2017 ▪ Revised 7 February 2018 ▪ Accepted 8 February 2018 ABSTRACT In order to understand water balance in plants, students must understand the relation between external representations at the macroscopic, microscopic, and submicroscopic levels. This study investigated how Slovenian students (N = 79) at the primary, secondary, and undergraduate tertiary levels understand water balance in plants. The science problem consisted of a text describing the setting, visualizations of the process occurring in a wilted plant stem, and five tasks. To determine students’ visual attention to the various elements of the tasks, we used eye tracking and focused on the total fixation duration in particular areas of interest. As expected, primary school students showed less knowledge and understanding of the process than the secondary school and university students did. Students with correct answers spent less time observing the biological phenomena displayed at the macroscopic and submicroscopic levels than those with incorrect answers, and more often provided responses that combined the macro-, micro-, and submicroscopic levels of thought. -

Bacterial Wilt of Cucurbits Amy D

® ® KFSBOPFQVLCB?O>PH>¨ FK@LIKUQBKPFLK KPQFQRQBLCDOF@RIQROB>KA>QRO>IBPLRO@BP KLTELT KLTKLT G2023 Bacterial Wilt of Cucurbits Amy D. Timmerman, Extension Educator, Plant Pathology James A. Kalisch, Extension Associate, Entomology The fruit can also show symptoms with small water- This NebGuide covers the management and pre- soaked patches forming on the surface. Eventually these vention of bacterial wilt of cucurbits, which affects patches turn into shiny spots of dead tissue. cucumber, squash, muskmelon, pumpkin, and gourds. There are other causes for runners wilting that are observed in the garden, including squash vine borers and soil-borne fun- The vascular wilt disease caused by the bacterium Erwinia gal pathogens. A characteristic symptom of bacterial wilt is the tracheiphila affects members of the cucurbit family, includ- occasional creamy-white bacterial ooze that can be observed ing cucumber, squash, muskmelon, pumpkin, and gourd. in the xylem vascular bundles of an infected stem. Watermelon, however, is resistant to this disease and certain To observe the ooze, cut the stem crosswise near the varieties of cucumber and squash show varying degrees of ground and squeeze it. When the finger is pressed firmly resistance. You can recognize the disease by the severe wilting against the cut surface, and then slowly pulled away about of individual leaves during hot, sunny days, and within a week half an inch, the bacterial ooze will string out, forming fine, or two, the entire plant wilting with no recovery. shiny threads. Symptoms Bacterial wilt symptoms characteristically begin with the wilting of individual leaves or vines (Figure 1) during the heat of the day. -

Cotton Root Rot (Phymatotrichopsis Root Rot) and Its Management

PLPA-FC010-2016 COTTON ROOT ROT (PHYMATOTRICHOPSIS ROOT ROT) AND ITS MANAGEMENT Phymatotrichopsis root rot (also known as cotton root rot, Phymatotrichum root rot, Texas root rot and Ozonium root There is white to brown fungal growth on the surface of rot) is a major fungal disease of cotton occurring within large main roots near the lower stem, consisting of strands areas of Texas and Arizona, causing annual losses in Texas and a loose, cottony growth just below the soil surface alone of up to $29 million. The causal fungus is soilborne (Fig. 3). and has a host range of more than 1800 dicot plants. This disease only occurs in the southwestern United States and several northern states of Mexico. There has been no expansion of geographic range of the disease within North America. Diagnosis and Impact The disease develops late in the spring or early summer, as soil temperatures approach 82°F. About a day before the onset of visible symptoms , the leaves of infected plants feel noticeably hotter than surrounding, non-infected plants. The Fig. 3 Growth of cotton root rot fungus on root and first visible symptom is wilting (Fig. 1), which becomes base of stem. permanent by the third day, Wilt is usually seen when plants are flowering, sometimes earlier in the season, but not when plants are seedlings. A large number of plants may wilt simultaneously, but even within an affected area, wilting among plants is not simultaneous, sometimes occurring weeks apart. It is also possible to see non- symptomatic plants surrounded by diseased plants. -

Phymatotrichum Omni- Vorum

PERSISTENT STRANDS OF THE COTTON ROOT-ROT FUNGUS IN TEXAS' By HoMHR C. MCNAMARA, associate agronomist^ and R. E. WESTER and K. C. GuNN, assistant scientific aids, Division of Cotton and Other Fiber Crops and Diseases, Bureau of Plant Industry, United States Department of Agriculture INTRODUCTION The ability of the cotton root-rot fungus (Phymatotrichum omni- vorum (Shear) Dug.) (2) ^ to remain in the soil in a viable and infec- tious condition for a period of years, even when the fields are planted to nonsusceptible crops or kept in clean fallow, has been a problem of much concern to all mvestigators of this disease. Further observa- tions on the ability of this fungus to perpetuate itself in the soil for long periods were made possible during the summer of 1932, when plots that had been in clean fallow for several years or planted to nonsusceptible crops were returned to cotton. Even after a 5-year clean fallow, several centers of infection appeared in a half-acre plot during July and August. In the planning of experimental work on the control of cotton root rot, the nature and stage of the organism that is being dealt with must be considered. Clean fallows covering from 1 to 5 years and the use of nonsusceptible crops on infested areas have furnished con- ditions under which it has been possible to study the fungus in the soil on both cropped and uncropped plots. The colloidal nature of the Wilson and Houston clay soils presented special opportunities for studying the fungus in its natural state of growth.