Class Struggle As Reflection of Spain's Sociocultural Identity In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Selected Intermediate-Level Solo Piano Music Of

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2005 Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis Harumi Kurihara Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kurihara, Harumi, "Selected intermediate-level solo piano music of Enrique Granados: a pedagogical analysis" (2005). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3242. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3242 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. SELECTED INTERMEDIATE-LEVEL SOLO PIANO MUSIC OF ENRIQUE GRANADOS: A PEDAGOGICAL ANALYSIS A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Harumi Kurihara B.M., Loyola University, New Orleans, 1993 M.M.,University of New Orleans, 1997 August, 2005 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my sincere appreciation to my major professor, Professor Victoria Johnson for her expert advice, patience, and commitment to my monograph. Without her help, I would not have been able to complete this monograph. I am also grateful to my committee members, Professors Jennifer Hayghe, Michael Gurt, and Jeffrey Perry for their interest and professional guidance in making this monograph possible. I must also recognize the continued encouragement and support of Professor Constance Carroll who provided me with exceptional piano instruction throughout my doctoral studies. -

Siède French Svmbousm Through Its Premise That an Idea

Mester, Vol. xvz.v, (2000) Mario Vargas Llosa: Literatura, Art, and Goya's Ghost The relatíonship between the \'erbal and the pictorial—that is, between the written word and its \'isual representation, has exercised a particular fascination upon writers and ¿irtists throughout the ages. This nexus has operated both ways: artists have been fascinated by the manner in which writers manipúlate words, syntax and style to fashion new verbal realities (novéis, poems, plays), while writers for their part have succumbed to the allure of artists who utilise paint, ink, acid or crayons to créate new \'isual realities. Examples of this mutual attrac- tion and occasional cross-fertilisation between artists and writers abound. Perhaps no aesthetic movement illustrates the symbiosis be- tween literature and art more consistently and strikingly than fin ãc siède French svmboUsm through its premise that an idea could be expressed through form, the word orobjectrepresented beingnomore thím a sign to open up the pri\'ate world of the imagination. Thus, symbolist poets like Mallarmé, Verlaine and Rimbaud had their coun- terparts in painters like Redon, Moreau, Rops and Ensor—a spiritucd bond between the verbal and the plástic arts that has inspired exhibi- tions in importantmuseums,galleries andlibraries in cities as far apart as Melboume and Madrid.^ With respect to the Hispímic world, it is well-known that Sah ador Dalí and Federico García Lorca exercised considerable creative intlu- ence upon each other, while Dali also produced a series of one hundred wood engravings illustrating Dante's The Divine Comedi/. The early novéis of the Spanish Nobel Prize winner for literature, Camilo José Cela, were influenced by the power and the passion of Picasso's Guemica (1937), whose tortured images of mayhem in tum echo the scenes of murder cind mutilation in La familia de Pascual Duarte. -

Music in the Time of Goya

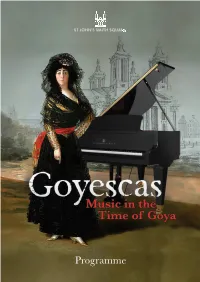

Music in the Time of Goya Programme ‘Goyescas’: Music in the Time of Goya Some of the greatest names in classical music support the Iberian and Latin American Music Society with their membership 2 November 2016, 7.00pm José Menor piano Daniel Barenboim The Latin Classical Chamber Orchestra featuring: Argentine pianist, conductor Helen Glaisher-Hernández piano | Elena Jáuregui violin | Evva Mizerska cello Nicole Crespo O’Donoghue violin | Cressida Wislocki viola and ILAMS member with special guest soloists: Nina Corti choreography & castanets Laura Snowden guitar | Christin Wismann soprano Opening address by Jordi Granados This evening the Iberian and Latin American Music Society (ILAMS) pays tribute to one of Spain’s most iconic composers, Enrique Granados (1867–1916) on the centenary year of his death, with a concert programme inspired by Granados’ greatest muse, the great Spanish painter Francisco de Goya y Lucientes (1746–1828), staged amidst the Baroque splendour of St John’s Smith Square – a venue which, appropriately, was completed not long before Goya’s birth, in 1728. Enrique Granados To pay homage to Granados here in London also seems especially fi tting given that the great Composer spent his fi nal days on British shores. Granados Will you drowned tragically in the English Channel along with his wife Amparo after their boat, the SS Sussex, was torpedoed by the Germans. At the height of his join them? compositional powers, Granados had been en route to Spain from New York where his opera, Goyescas, had just received its world premiere, and where he had also given a recital for President Woodrow Wilson; in his lifetime Granados was known as much for his virtuoso piano playing as for his talent as a composer. -

Granados: Goyescas

Goyescas Enrique Granados 1. Los Requiebros [9.23] 2. Coloquio en La Reja [10.53] 3. El Fandango de Candil [6.41] 4. Quejas, ó la Maja y el Ruiseñor [6.22] 5. El Amor y la Muerte: Balada [12.43] 6. Epilogo: Serenata del Espectro [7.39] Total Timings [54.00] Ana-Maria Vera piano www.signumrecords.com The Goyescas suite has accompanied me throughout with her during the recording sessions and felt G my life, and I always knew that one day I would generous and grounded like never before. The music attempt to master it.The rich textures and came more easily as my perspectives broadened aspiring harmonies, the unfurling passion and I cared less about perfection. Ironically this is tempered by restraint and unforgiving rhythmic when you stand the best chance of approaching precision, the melancholy offset by ominous, dark your ideals and embracing your audience. humour, the elegance and high drama, the resignation and the hopefulness all speak to my sense of © Ana-Maria Vera, 2008 being a vehicle, offeeling the temperature changes, the ambiguity, and the emotion the way an actor might live the role of a lifetime. And so this particular project has meant more to me than almost any in my career. Catapulted into the limelight as a small child, I performed around the globe for years before realising I had never had a chance to choose a profession for myself. Early success, rather than going to my head, affected my self-confidence as a young adult and I began shying away from interested parties, feeling the attention wasn't deserved and therefore that it must be of the wrong kind. -

Francisco De Goya

Francisco de Goya, pintor a caballo entre el clasicismo y el romanticismo que se enmarca en el periodo de la Ilustración del siglo XVIII, es una figura imprescindible de la historia del arte español. El artista vive en una constante dicotomía, puesto que trabaja para la corte y, al mismo tiempo, introduce la crítica social en su obra y se interesa por temas poco habituales, como el lado oscuro del ser humano. De esta manera, revoluciona el arte con obras maestras como La maja desnuda o La familia de Carlos IV. Su talento a la hora de plasmar a la perfección la personalidad de sus personajes en sus retratos y de captar un sentido de la luz preciso y delicado queda reflejado en sus pinturas al óleo, sus frescos, sus aguafuertes, sus litografías y sus dibujos. Esta guía estructurada y concisa te invita a descubrir todos los secretos de Francisco de Goya, desde su contexto, su biografía y las características de su obra hasta un análisis de sus trabajos principales, como la Adoración del nombre de Dios por los ángeles, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos o La maja desnuda, entre otros. Te ofrecemos las claves para: conocer la España de los siglos XVIII y XIX, que pierde importancia a nivel mundial y que se muestra reacia a toda idea liberal que provenga de fuera de sus fronteras; descubrir los detalles sobre la vida de Francisco de Goya, artista lleno de contradicciones que se convierte en una de las figuras clave de la historia del arte español; analizar una selección de sus obras clave, como La maja desnuda, la Adoración del nombre de Dios por los ángeles, El sueño de la razón produce monstruos o La familia de Carlos IV; etc. -

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL

ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: NATIONAL CHARACTER AS EXPRESSED IN PIANO LITERATURE Yong Sook Park, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2005 Dissertation directed by: Bradford Gowen, Professor of Music In the middle of the 19th century, many composers living outside of mainstream musical countries such as Germany and France attempted to establish their own musical identity. A typical way of distinguishing themselves from German, French, and Italian composers was to employ the use of folk elements from their native lands. This resulted in a vast amount of piano literature that was rich in national idioms derived from folk traditions. The repertoire reflected many different national styles and trends. Due to the many beautiful, brilliant, virtuosic, and profound ideas that composers infused into these nationalistic works, they took their rightful place in the standard piano repertoire. Depending on the compositional background or style of the individual composers, folk elements were presented in a wide variety of ways. For example, Bartók recorded many short examples collected from the Hungarian countryside and used these melodies to influence his compositional style. Many composers enhanced and expanded piano technique. Liszt, in his Hungarian Rhapsodies, emphasized rhythmic vitality and virtuosic technique in extracting the essence of Hungarian folk themes. Chopin and Szymanowski also made use of rhythmic figurations in their polonaises and mazurkas, often making use of double-dotted rhythms. Obviously, composers made use of nationalistic elements to add to the piano literature and to expand the technique of the piano. This dissertation comprises three piano recitals presenting works of: Isaac Albeniz, Bela Bartók, Frédéric Chopin, Enrique Granados, Edvard Grieg, Franz Liszt, Frederic Rzewski, Alexander Scriabin, Karol Szymanowski, and Peter Ilich Tchaikovsky. -

Repertoire Report 2012-13 Season Group 7 & 8 Orchestras

REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. Conductor Orchestra Soloist(s) Actor, Lee DIVERTIMENTO FOR SMALL ORCHESTRA Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Adams, John SHORT RIDE IN A FAST MACHINE Oct. 13, 2012 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Bach, J. S. TOCCATA AND FUGUE, BWV 565, D MINOR Oct. 27, 2012 Charles Latshaw Bloomington Symphony (STOWKOWSKI) (STOWKOWSKI,) Orchestra Barber, Samuel CONCERTO, VIOLIN AND ORCHESTRA, Feb. 2, 2013 Jason Love The Columbia Orchestra Madeline Adkins, violin OPUS 14 Barber, Samuel OVERTURE TO THE SCHOOL FOR Feb. 9, 2013 Herschel Kreloff Civic Orchestra of Tucson SCANDAL Bartok, Béla ROMANIAN FOLK DANCES Sep. 29, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, PIANO, NO. 5 IN E-FLAT Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Sayaka Jordan, piano MAJOR, OP. 73 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CONCERTO, VIOLIN, IN D MAJOR, OPUS Nov. 17, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Sharon Roffman, violin 61 Beethoven, Ludwig V. CORIOLAN: OVERTURE, OPUS 62 Mar. 9, 2013 Fouad Fakhouri Fayetteville Symphony Orchestra Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac Beethoven, Ludwig V. EGMONT: OVERTURE, OPUS 84 Oct. 20, 2012 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SONATA FOR VIOLIN AND PIANO, Apr. 13, 2013 Steven Lipsitt Boston Classical Orchestra "SPRING" III RONDO Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 1 IN C MAJOR, OPUS 21 Apr. 27, 2013 Emily Ray Mission Chamber Orchestra Beethoven, Ludwig V. SYMPHONY NO. 3 IN E-FLAT MAJOR, Apr. 14, 2013 Joel Lazar Symphony of the Potomac OPUS 55 Page 1 of 13 REPERTOIRE REPORT 2012-13 SEASON GROUP 7 & 8 ORCHESTRAS Composer Work First Perf. -

María Del Carmen Opera in Three Acts

Enrique GRANADOS María del Carmen Opera in Three Acts Veronese • Suaste Alcalá • Montresor Wexford Festival Opera Chorus National Philharmonic Orchestra of Belarus Max Bragado-Darman CD 1 43:33 5 Yo también güervo enseguía Enrique (Fuensanta, María del Carmen) 0:36 Act 1 6 ¡Muy contenta! y aquí me traen, como aquel GRANADOS 1 Preludio (Orchestra, Chorus) 6:33 que llevan al suplicio (María del Carmen) 3:46 (1867-1916) 2 A la paz de Dios, caballeros (Andrés, Roque) 1:28 7 ¡María del Carmen! (Pencho, María del Carmen) 5:05 3 Adiós, hombres (Antón, Roque) 2:27 8 ¿Y qué quiere este hombre a quien maldigo María del Carmen 4 ¡Mardita sea la simiente que da la pillería! desde el fondo de mi alma? (Pepuso, Antón) 1:45 (Javier, Pencho, María del Carmen) 4:10 Opera in Three Acts 9 5 ¿Pos qué es eso, tío Pepuso? ¡Ah!, tío Pepuso, lléveselo usted (Roque, Pepuso, Young Men) 3:04 (María del Carmen, Pepuso, Javier, Pencho) 0:32 Libretto by José Feliu Codina (1845-1897) after his play of the same title 0 6 ¡Jesús, la que nos aguarda! Ya se fue. Alégrate corazón mío Critical Edition: Max Bragado-Darman (Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 1:49 (María del Carmen, Javier) 0:55 ! ¡Viva María el Carmen y su enamorao, Javier! Published by Ediciones Iberautor/Instituto Complutense de Ciencias Musicales 7 Una limosna para una misa de salud… (Canción de la Zagalica) (María del Carmen, (Chorus, Domingo) 5:22 @ ¡Pencho! ¡Pencho! (Chorus) ... Vengo a delatarme María del Carmen . Diana Veronese, Soprano Fuensanta, Don Fulgencio, Pepuso, Roque) 6:59 8 Voy a ver a mi enfermo, el capellán para salvar a esta mujer (Pencho, Domingo, Concepción . -

Ignacio Zuloaga

Artigrama, núm. 25, 2010, pp. 165-183. ISSN: 0213-1498 La pasión por Goya en Zuloaga y su círculo Jesús Pedro Lorente Lorente* Resumen Este artículo reúne dos categorías de argumentos para mostrar que Ignacio Zuloaga fue como artista uno de los más señalados cultivadores de pinturas goyescas en cuestiones icono- gráficas y estéticas en las que tuvo a su vez seguidores; pero también un peritísimo goyista, quien coleccionó ávidamente obras del aragonés e incentivó a otros coleccionistas sirviéndoles de intermediario, por lo que figuran en lugar destacado en su museo de Zumaya y en tantos otros de todo el mundo. Palabras clave Goya, Zuloaga, gusto, coleccionismo. Abstract This article proposes two lines of argumentation, in order to show on the one hand that Ignacio Zuloaga was, as an artist, one of the most distinguished cultivators of goyesque paintings both regarding iconography and in aesthetic terms, leading the way to some emulators; but he also was, on the other hand, a knowledgeable expert in Goya, whose works he avidly collected, helping others to do so as well, as a result of which they figure prominently in his Zumaya museum and in others around the world. Key words Goya, Zuloaga, taste, collecting. * * * * * Uno de los más fascinantes temas de investigación para los historiado- res del arte es rastrear la trascendencia de los grandes artistas y sus obras, tanto en lo que respecta a al influjo en otros artistas como en lo relativo a su fortuna crítica entre los estudiosos. Ambos aspectos cuentan ya con importantes aportaciones en el caso de Goya: para lo segundo el libro de referencia —donde curiosamente sólo se nombra de pasada a Zuloaga, uno de los mayores activistas en reivindicar públicamente la memoria de Goya—, sigue siendo el publicado por Nigel Glendinning en 1977, Goya and His Critics;1 mientras que sobre la descendencia artística goyesca sentó * Profesor Titular en el Departamento de Historia del Arte de la Universidad de Zaragoza. -

Pasodoble PSDB

Documentación técnica Pasodoble PSDB l Pasodoble, o Paso Doble, es un baile que se originó en España entre 1533 y E1538. Podría ser considerado, en esen- cia, como el estandarte sonoro que le distingue en todas partes del mundo. Se trata de un ritmo alegre, pleno de brío, castizo, flamenco unas veces, pero siempre reflejo del garbo y más ge- nuino sabor español. Se trata de una variedad musical dentro de la forma «marcha» en com- pás binario de 2/4 o 6/8 y tiempo «allegro mo- derato», frecuentemente compuesto en tono menor, utilizada indistintamente para desfiles militares y para espectáculos taurinos. Aunque no está del todo claro, parece ser que el pasodoble tiene sus orígenes en la tonadilla escénica, –creada por el flautista es- pañol Luis de Misón en 1727– que era una Este tipo de macha ligera fue adoptada composición que en la primera mitad del siglo como paso reglamentario para la infantería es- XVII servía como conclusión de los entreme- pañola, en la que su marcha está regulada en ses y los bailes escénicos y que después, 120 pasos por minuto, con la característica es- desde mediados del mismo siglo, se utilizaba pecial que hace que la tropa pueda llevar el como intermedio musical entre los actos de las paso ordinario. Tras la etapa puramente militar comedias. –siglo XVIII– vendría la fase de incorporación de elementos populares –siglo XIX–, con la El pasodoble siempre ha estado aso- adición de elementos armónicos de la seguidi- ciado a España y podemos decir que es el baile lla, jota, bolero, flamenco.. -

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 the Flamenco

Crying Across the Ocean: Considering the Origins of Farruca in Argentina Julie Galle Baggenstoss March 22, 2014 The flamenco song form farruca is popularly said to be of Celtic origin, with links to cultural traditions in the northern Spanish regions of Galicia and Asturias. However, a closer look at the song’s traits and its development points to another region of origin: Argentina. The theory is supported by an analysis of the song and its interpreters, as well as Spanish society at the time that the song was invented. Various authors agree that the song’s traditional lyrics, shown in Table 1, exhibit the most obvious evidence of the song’s Celtic origin. While the author of the lyrics is not known, the word choice gives some clues about the person who wrote them. The lyrics include the words farruco and a farruca, commonly used outside of Galicia to refer to a person who is from that region of Spain. The use of the word farruco/a indicates that the author was not in Galicia at the time the song was written. Letra tradicional de farruca Una Farruca en Galicia amargamente lloraba porque a la farruca se le había muerto el Farruco que la gaita le tocaba Table 1: Farruca song lyrics Sources say the poetry likely expresses nostalgia for Galicia more than the perspective of a person in Galicia (Ortiz). A large wave of Spanish immigrants settled in what is now called the Southern Cone of South America, including Argentina and Uruguay, during the late 19th century, when the flamenco song farruca was first documented as a sung form of flamenco. -

A La Cubana: Enrique Granados's Cuban Connection

UC Riverside Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review Title A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/90b4c4cb Journal Diagonal: An Ibero-American Music Review, 2(1) ISSN 2470-4199 Author de la Torre, Ricardo Publication Date 2017 DOI 10.5070/D82135893 License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California A la cubana: Enrique Granados’s Cuban Connection RICARDO DE LA TORRE Abstract Cuba exerted a particular fascination on several generations of Spanish composers. Enrique Granados, himself of Cuban ancestry, was no exception. Even though he never set foot on the island—unlike his friend Isaac Albéniz—his acquaintance with the music of Cuba became manifest in the piano piece A la cubana, his only work with overt references to that country. This article proposes an examination of A la cubana that accounts for the textural and harmonic characteristics of the second part of the piece as a vehicle for Granados to pay homage to the piano danzas of Cuban composer Ignacio Cervantes. Also discussed are similarities between A la cubana and one of Albéniz’s own piano pieces of Caribbean inspiration as well as the context in which the music of then colonial Cuba interacted with that of Spain during Granados’s youth, paying special attention to the relationship between Havana and Catalonia. Keywords: Granados, Ignacio Cervantes, Havana, Catalonia, Isaac Albéniz, Cuban-Spanish musical relations Resumen Varias generaciones de compositores españoles sintieron una fascinación particular por Cuba. Enrique Granados, de ascendencia cubana, no fue la excepción.