An Analysis of Pre and Post S.R. Bommai Scenario with Reference to President's Rule in States Dr

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

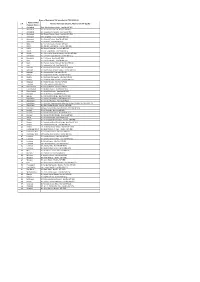

S N. Name of TAC/ Telecom District Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms

Name of Nominated TAC members for TAC (2020-22) Name of TAC/ S N. Name of Nominee [Sh./Smt./Ms] Hon’ble MP (LS/RS) Telecom District 1 Allahabad Prof. Rita Bahuguna Joshi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 2 Allahabad Smt. Keshari Devi Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 3 Allahabad Sh. Vinod Kumar Sonkar, Hon’ble MP (LS) 4 Allahabad Sh. Rewati Raman Singh, Hon’ble MP (RS) 5 Azamgarh Smt. Sangeeta Azad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 6 Azamgarh Sh. Akhilesh Yadav, Hon’ble MP (LS) 7 Azamgarh Sh. Rajaram, Hon’ble MP (RS) 8 Ballia Sh. Virendra Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 9 Ballia Sh. Sakaldeep Rajbhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 10 Ballia Sh. Neeraj Shekhar, Hon’ble MP (RS) 11 Banda Sh. R.K. Singh Patel, Hon’ble MP (LS) 12 Banda Sh. Vishambhar Prasad Nishad, Hon’ble MP (RS) 13 Barabanki Sh. Upendra Singh Rawat, Hon’ble MP (LS) 14 Barabanki Sh. P.L. Punia, Hon’ble MP (RS) 15 Basti Sh. Harish Dwivedi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 16 Basti Sh. Praveen Kumar Nishad, Hon’ble MP (LS) 17 Basti Sh. Jagdambika Pal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 18 Behraich Sh. Ram Shiromani Verma, Hon’ble MP (LS) 19 Behraich Sh. Brijbhushan Sharan Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 20 Behraich Sh. Akshaibar Lal, Hon’ble MP (LS) 21 Deoria Sh. Vijay Kumar Dubey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 22 Deoria Sh. Ravindra Kushawaha, Hon’ble MP (LS) 23 Deoria Sh. Ramapati Ram Tripathi, Hon’ble MP (LS) 24 Faizabad Sh. Ritesh Pandey, Hon’ble MP (LS) 25 Faizabad Sh. Lallu Singh, Hon’ble MP (LS) 26 Farrukhabad Sh. -

Parliament of India R a J Y a S a B H a Committees

Com. Co-ord. Sec. PARLIAMENT OF INDIA R A J Y A S A B H A COMMITTEES OF RAJYA SABHA AND OTHER PARLIAMENTARY COMMITTEES AND BODIES ON WHICH RAJYA SABHA IS REPRESENTED (Corrected upto 4th September, 2020) RAJYA SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI (4th September, 2020) Website: http://www.rajyasabha.nic.in E-mail: [email protected] OFFICERS OF RAJYA SABHA CHAIRMAN Shri M. Venkaiah Naidu SECRETARY-GENERAL Shri Desh Deepak Verma PREFACE The publication aims at providing information on Members of Rajya Sabha serving on various Committees of Rajya Sabha, Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees, Joint Committees and other Bodies as on 30th June, 2020. The names of Chairmen of the various Standing Committees and Department-related Parliamentary Standing Committees along with their local residential addresses and telephone numbers have also been shown at the beginning of the publication. The names of Members of the Lok Sabha serving on the Joint Committees on which Rajya Sabha is represented have also been included under the respective Committees for information. Change of nominations/elections of Members of Rajya Sabha in various Parliamentary Committees/Statutory Bodies is an ongoing process. As such, some information contained in the publication may undergo change by the time this is brought out. When new nominations/elections of Members to Committees/Statutory Bodies are made or changes in these take place, the same get updated in the Rajya Sabha website. The main purpose of this publication, however, is to serve as a primary source of information on Members representing various Committees and other Bodies on which Rajya Sabha is represented upto a particular period. -

Forestry Interventions to Be Seen by July 2018

Forestry Interventions to Be Seen By July 2018 Effects of forestry interventions for the Clean Ganga Mission should start becoming visible by July 2018. Cleaning and conserving the Ganga has to be seen also from the economic point of view and not just from the religious point of view as crores of people depend on this river for their livelihood.The funds allocated for this task must be use efficiently and not spent for the sake of spending, said the Union Minister for Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Uma Bharti. She was speaking at the inauguration of a two-day national level stakeholders’ meet on preparation of the DPR on forestry interventions for the Ganga at the Forest Research Institute. Bharti said she was never against construction of power projects on rivers but stressed that dam designs should not alter the flow or character of the river. She said, “We have to ensure that Rs20,000 crore allocated for this mission to be spent across four years is used effectively and not spent just for the sake of spending it. Uttarakhand has immense scope for creating a new development model. I want to see Uttarakhand develop as a hub of medicinal herbs so that medicines made in Uttarakhand from these herbs replace the Chinese medicines in the international market.” “Apart from ensuring efficient use of funds and timely action for Ganga, we also have to ensure convergence of the intentions of those in Delhi with the position of those in the States to prevent a situation as created by declaration of the Bhagirathi eco sensitive zone which was well intended but had elicited public opposition,” said Bharti.Minister of Environment, Forests and Climate Change, Prakash Javadekar said the Government was in the process of facilitating zero liquid discharge from identified leather tanneries along the Ganga while censors have been installed in most of the other identified polluting industrial units along the Ganga to monitor pollution. -

S28 - UTTARANCHAL PC No

General Elections, 1999 Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies Candidate No & Name Party Votes State-UT Code & Name : S28 - UTTARANCHAL PC No. & Name : 1-Tehri Garhwal AC Number and AC Name 1-Uttarkashi 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 41539 2 Munna Chauhan SP 7463 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 623 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 33095 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3855 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 842 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 1181 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 390 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 88988 AC Number and AC Name 2-Tehri 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 34662 2 Munna Chauhan SP 2401 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 700 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 31401 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3697 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 715 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 314 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 528 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 74418 AC Number and AC Name 3-Deoprayag 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 35091 2 Munna Chauhan SP 1856 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 1127 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 26332 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3848 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 652 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 293 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 597 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 69796 AC Number and AC Name 423-Mussoorie 1 Manabendra Shah BJP 67592 2 Munna Chauhan SP 6103 3 Rajeev Rawat BSP 3281 4 Vijay Bahuguna INC 61752 5 Vidya Sagar Nautiyal CPI 3339 6 Darshan Lal Dimiri ABHM 702 7 Bishnu Pal Singh Rawat UKKD 368 8 Virendra Singh Negi IND 280 Total Valid Votes for the AC : 143417 Election Commission of India - GE-1999 Assembly Segment Details for PCs Page 1 of 11 General Elections, 1999 Details for Assembly Segments of Parliamentary Constituencies -

List of Successful Candidates

11 - LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATES CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 1 Nagarkurnool Dr. Manda Jagannath INC 2 Nalgonda Gutha Sukender Reddy INC 3 Bhongir Komatireddy Raj Gopal Reddy INC 4 Warangal Rajaiah Siricilla INC 5 Mahabubabad P. Balram INC 6 Khammam Nama Nageswara Rao TDP 7 Aruku Kishore Chandra Suryanarayana INC Deo Vyricherla 8 Srikakulam Killi Krupa Rani INC 9 Vizianagaram Jhansi Lakshmi Botcha INC 10 Visakhapatnam Daggubati Purandeswari INC 11 Anakapalli Sabbam Hari INC 12 Kakinada M.M.Pallamraju INC 13 Amalapuram G.V.Harsha Kumar INC 14 Rajahmundry Aruna Kumar Vundavalli INC 15 Narsapuram Bapiraju Kanumuru INC 16 Eluru Kavuri Sambasiva Rao INC 17 Machilipatnam Konakalla Narayana Rao TDP 18 Vijayawada Lagadapati Raja Gopal INC 19 Guntur Rayapati Sambasiva Rao INC 20 Narasaraopet Modugula Venugopala Reddy TDP 21 Bapatla Panabaka Lakshmi INC 22 Ongole Magunta Srinivasulu Reddy INC 23 Nandyal S.P.Y.Reddy INC 24 Kurnool Kotla Jaya Surya Prakash Reddy INC 25 Anantapur Anantha Venkata Rami Reddy INC 26 Hindupur Kristappa Nimmala TDP 27 Kadapa Y.S. Jagan Mohan Reddy INC 28 Nellore Mekapati Rajamohan Reddy INC 29 Tirupati Chinta Mohan INC 30 Rajampet Annayyagari Sai Prathap INC 31 Chittoor Naramalli Sivaprasad TDP 32 Adilabad Rathod Ramesh TDP 33 Peddapalle Dr.G.Vivekanand INC 34 Karimnagar Ponnam Prabhakar INC 35 Nizamabad Madhu Yaskhi Goud INC 36 Zahirabad Suresh Kumar Shetkar INC 37 Medak Vijaya Shanthi .M TRS 38 Malkajgiri Sarvey Sathyanarayana INC 39 Secundrabad Anjan Kumar Yadav M INC 40 Hyderabad Asaduddin Owaisi AIMIM 41 Chelvella Jaipal Reddy Sudini INC 1 GENERAL ELECTIONS,INDIA 2009 LIST OF SUCCESSFUL CANDIDATE CONSTITUENCY WINNER PARTY Andhra Pradesh 42 Mahbubnagar K. -

Eighteenth Report

STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY 18 (2010-2011) FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA MINISTRY OF NEW AND RENEWABLE ENERGY DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2011-2012) EIGHTEENTH REPORT LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2011/Sravana, 1933 (Saka) EIGHTEENTH REPORT STANDING COMMITTEE ON ENERGY (2010-2011) (FIFTEENTH LOK SABHA) MINISTRY OF NEW AND RENEWABLE ENERGY DEMANDS FOR GRANTS (2011-2012) Presented to Lok Sabha on 17.8.2011 Laid in Rajya Sabha on 17.8.2011 LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT NEW DELHI August, 2011/Sravana, 1933 (Saka) C.O.E. No. 208 Price : Rs. 70.00 © 2011 BY LOK SABHA SECRETARIAT Published under Rule 382 of the Rules of Procedure and Conduct of Business in Lok Sabha (Fourteenth Edition) and printed by Jainco Art India, New Delhi-110 005. CONTENTS PAGE COMPOSITION OF THE COMMITTEE (2010-11) .......................................... (iii) INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................ (v) REPORT PART I NARRATION ANALYSIS I. Introductory .................................................................................. 1 II. Eleventh Five Year Plan — Review of Progress................ 4 III. Analysis of the Demands for Grants of the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (2011-12) ................................. 9 IV. Major Programmes of New and Renewable Power ......... 13 A. National Solar Mission ...................................................... 13 B. Wind Energy Programme ................................................. 18 C. Remote Village Electrification Programme ................... 20 D. -

1. Reliance Jio Launches Jiomoney Wallet Service 2. Harish Rawat Led Congress Government Wins the Floor Test in Uttarakhand Asse

1. Reliance Jio launches JioMoney Wallet service Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd's (R-Jio) digital wallet app JioMoney has made a quiet debut on Google Play Store. JioMoney is a semi-closed prepaid wallet that aims to enable mobile-based transactions, where customers can store money and use it for purchasing goods and services.With its Jio Money digital wallet, the company aims to enable mom-and-pop shops to accept cashless payments through smartphones. Get detailed news coverage in The Times of India Bonus Learning Material Learn more about Reliance Jio Learn more about JioMoney Wallet Get more Current Affairs related to Startups 2. Harish Rawat led Congress Government wins the Floor Test in Uttarakhand Assembly The Supreme Court on Wednesday put the Harish Rawat-led Congress government back in the saddle in Uttarakhand, allowing the central government to revoke President’s rule following Rawat’s victory in Tuesday’s floor test. A bench of Justice Dipak Misra and Justice Shiva Kirti Singh accepted Attorney General Mukul Rohatgi’s plea that the Centre wanted to withdraw the proclamation for President’s rule in the course of the day to enable Rawat to take charge as chief minister. Get detailed news coverage in The Indian Express Bonus Learning Material Learn more about Harish Rawat Learn more about Congress Government Get more Current Affairs related to Appointments 3. US actor William Schallert passes away He appeared in everything from Star Trek to the Oscar-winning film In The Heat Of The Night, as well as serving as president of the Screen Actors Guild from 1979 to 1981. -

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information Relating to Parliamentary and Other Matters) ______No

LOK SABHA ___ BULLETIN-PART II (General Information relating to Parliamentary and other matters) ____________________________________________________________________________ No. 2566 - 2569] [Thursday, July 8, 2021/ Ashadha 17, 1943 (Saka) No. 2566 Table Office Process to submit the notice as well as procedure to call the attention of the Minister to a matter of urgent public importance Under Rule 197 Hon’ble members are informed that an e-portal has been put in place to facilitate the members of Lok Sabha to submit their notices online to call the attention of the Minister to any matter of urgent public importance under rule 197 (Calling Attention). However, the printed form is also available in the Parliamentary Notice Office to submit the notice to call the attention of Minister. The following process to submit the notice as well as procedure to call the attention of Minister under Rule 197 will be followed: - (i) Notices may be submitted either through printed form or online; (ii) No member shall give more than two notices for any one sitting; (iii) A notice signed by more than one member to call the attention of Minister shall be deemed to have been given by the first signatory only; (iv) Notices for a sitting received upto 1000 hours shall be deemed to have been received at 1000 hours on that day and a ballot shall be held to determine the relative priority of each such notice on the same subject. Notices received after 1000 hours shall be deemed to have been given for the next sitting; (v) Notices received during a week commencing from its first sitting till 1000 hours on the last day of the week on which the House sits, shall be valid for that week. -

A Disaster, Conveniently Forgotten

A Disaster, Conveniently Forgotten Sushmita I had written this article after our visit to Uttarakhand post disaster for a study on the impacted livelihoods of the people, initiated by Tata Institute of Social Sciences. I never published this. But the recent reports on the situation of Uttarakhand and rehabilitation measures (not ) taken so far are disturbing and hence I found it relevant to publish some of my observations from the fateful months that had followed the disaster. Dharchula is a curios place. It lies on the India Nepal border in Pithoragarh district, and to reach there one just needs to cross a bridge on the Kali river, which emanates from further north through the glaciers along the watershed with the uppermost Humla Karnali and ultimately flows down to Uttar Pradesh to merge into Ghaghra river, a tributary to the Ganges. Any morning in Dharchula is spent hearing the songs and sounds of protests coming from across the river. These are voices of dissent on Nepal Government's inaction on disaster related relief and rehabilitation methods. Dharchula's district tehshil office is a daily witness of people from nearby and far off villages who are directly or indirectly affected by the floods on the fateful night of 16th and 17th June. While some people lost their loved ones, many lost their houses. Some villages like Sobla that were the centre points of all economic activity, got completely washed away. The flock of people visiting the tehshil office is a furious lot. They are angry, they are outraged at Government's inaction and slow response. -

Conference Booklet

MINISTRY OF EXTERNAL AFFAIRS Government of India Conference Booklet 2017 4-5 July 2017 u New Delhi CHARTING THE COURSE FOR INDIA-ASEAN RELATIONS FOR THE NEXT 25 YEARS 2017 Contents Message by Smt. Sushma Swaraj, Minister of External Affairs, India 3 Message by Smt. Preeti Saran, Secretary (East), Ministry of External Affairs, India 5 Message by Dr A. Didar Singh, General Secretary, FICCI 7 Message by Mr Sunjoy Joshi, Director, Observer Research Foundation 9 Introduction to the Delhi Dialogue 2017 12 Concept Note 17 Key Debates 24 Agenda for 2017 Delhi Dialogue 29 Speakers: Ministerial Session 39 Speakers: Business & Academic Sessions 51 Minister of External Affairs विदेश मं配셀 India भारत सुषमा स्वराज Sushma Swaraj Message am happy that the 9th edition of the Delhi Dialogue is being jointly hosted by the Ministry of External Affairs, Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry and the Observer Research Foundation from July 4-5, 2017. On behalf Iof the Government of India, I extend a very warm welcome to all the participants. This year India and ASEAN celebrate 25 years of their Dialogue Partnership, 15 years of Summit Level interaction and 5 years of Strategic Partnership. Honouring the long standing friendship, the theme for this year’s Dialogue is aptly titled ‘Chart- ing the Course for India-ASEAN Relations for the Next 25 Years.’ At a time when the world is experiencing a number of complex challenges and transitions, consolidating and institutionalising old friendships is key to the growth and stability of our region. I am confident the different panels of the Delhi Dialogue will discuss the various dimensions of the theme and throw new light into the possible ways for India and ASEAN to move forward on common traditional and non-traditional challenges. -

Seats (Won by BJP in 2014 LS Elections) Winner BJP Candidate (2014 LS Election UP) Votes for BJP Combined Votes of SP and BSP Vo

Combined Seats (Won By BJP in Winner BJP Candidate (2014 LS Election Votes for Votes of SP Vote 2014 LS Elections) UP) BJP and BSP Difference Saharanpur RAGHAV LAKHANPAL 472999 287798 185201 Kairana HUKUM SINGH 565909 489495 76414 Muzaffarnagar (DR.) SANJEEV KUMAR BALYAN 653391 413051 240340 Bijnor KUNWAR BHARTENDRA 486913 511263 -24350 Nagina YASHWANT SINGH 367825 521120 -153295 Moradabad KUNWER SARVESH KUMAR 485224 558665 -73441 Rampur DR. NEPAL SINGH 358616 491647 -133031 Sambhal SATYAPAL SINGH 360242 607708 -247466 Amroha KANWAR SINGH TANWAR 528880 533653 -4773 Meerut RAJENDRA AGARWAL 532981 512414 20567 Baghpat DR. SATYA PAL SINGH 423475 355352 68123 Ghaziabad VIJAY KUMAR SINGH 758482 280069 478413 Gautam Buddha 517727 81975 Nagar DR.MAHESH SHARMA 599702 Bulandshahr BHOLA SINGH 604449 311213 293236 Aligarh SATISH KUMAR 514622 454170 60452 Hathras RAJESH KUMAR DIWAKER 544277 398782 145495 Mathura HEMA MALINI 574633 210245 364388 Agra DR. RAM SHANKAR KATHERIA 583716 418161 165555 Fatehpur Sikri BABULAL 426589 466880 -40291 Etah RAJVEER SINGH (RAJU BHAIYA) 474978 411104 63874 Aonla DHARMENDRA KUMAR 409907 461678 -51771 Bareilly SANTOSH KUMAR GANGWAR 518258 383622 134636 Pilibhit MANEKA SANJAY GANDHI 546934 436176 110758 Shahjahanpur KRISHNA RAJ 525132 532516 -7384 Kheri AJAY KUMAR 398578 448416 -49838 Dhaurahra REKHA 360357 468714 -108357 Sitapur RAJESH VERMA 417546 522689 -105143 Hardoi ANSHUL VERMA 360501 555701 -195200 Misrikh ANJU BALA 412575 519971 -107396 Unnao SWAMI SACHCHIDANAND HARI SAKSHI 518834 408837 109997 Mohanlalganj -

Uttarakhand Pre-Election Tracker Survey, Round-2, January 2017

Uttarakhand Pre-Election Tracker Survey, Round-2, January 2017 About the Survey This analysis is based on the second round of the pre-election tracker survey conducted in Uttarakhand by Lokniti, Centre for the Study of Developing Societies (CSDS), Delhi, for ABP News. The survey was conducted from January 15 through January 20, 2017 among 1845 voters in 98 locations (polling stations) spread across 20 assembly constituencies. These are the same constituencies and polling stations where Lokniti had conducted the first round of the tracker survey in December 2016. The sampling design adopted was Multi-stage random sampling. The assembly constituencies where the survey was conducted were randomly selected using the probability proportional to size method. Thereafter, five polling stations within each of the sampled constituencies were selected using the systematic random sampling method. Finally, the respondents were also randomly selected from the electoral rolls of the sampled polling stations. Before going to the field for the survey, field investigators were imparted training about the survey method and interviewing techniques at a day-long training workshop held in Srinagar, Garhwal. The field investigators conducted face-to-face interviews of the respondents in Hindi asking them a set of standardized questions. The duration of an interview was about 15 minutes. The survey could not be conducted at two locations in two assembly seats. At some locations the non-availability of sampled respondents or difficulty in finding households necessitated replacements or substitutions. Meanwhile, inaccessibility of some of the areas of the state due to snowfall resulted in a low completion rate in some constituencies.