GFP Purification

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Purification Student Manual

Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Purification Student Manual "Bioengineered DNA was, weight for weight, the most valuable material in the world. A single microscopic bacterium, too small to see with the human eye, but containing the gene for a heart attack enzyme, streptokinase, or for "ice-minus" which prevented frost damage to crops, might be worth 5 billion dollars to the right buyer." Michael Crichton - Jurassic Park Contents Lesson 1 Genetic Transformation Review—Finding the Green Fluorescent Molecule Lesson 2 Inoculation—Growing a Cell Culture Lesson 3 Purification Phase 1—Bacterial Concentration and Lysis Lesson 4 Purification Phase 2—Removing Bacterial Debris Lesson 5 Purification Phase 3—Protein Chromatography 26 Lesson 1 Finding the Green Fluorescent Molecule Genetic Transformation Review In Bio-Rad Kit 1, you performed a genetic transformation of E. coli bacterial cells. The results of this procedure were colonies of cells that fluoresced when exposed to ultraviolet light. This is not a normal phenotype (characteristic) for E.coli. You were then asked to fig- ure out a way to determine which molecule was becoming fluorescent under UV light. After determining that the pGLO plasmid DNA was not responsible for the fluorescence under the UV light, you concluded that it was not the plasmid DNA that was fluorescing in response to the ultraviolet light within the cells. This then led to the next hypothesis that if it is not the DNA fluorescing when exposed to the UV light, then it must be a protein that the new DNA pro- duces within the cells. 1. Proteins. a. What is a protein? b. -

Protocols and Tips in Protein Purification

Department of Molecular Biology & Biotechnology Protocols and tips in protein purification or How to purify protein in one day Second edition 2018 2 Contents I. Introduction 7 II. General sequence of protein purification procedures 9 Preparation of equipment and reagents 9 Preparation and use of stock solutions 10 Chromatography system 11 Preparation of chromatographic columns 13 Preparation of crude extract (cell free extract or soluble proteins fraction) 17 Pre chromatographic steps 18 Chromatographic steps 18 Sequence of operations during IEC and HIC 18 Ion exchange chromatography (IEC) 19 Hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC) 21 Gel filtration (SEC) 22 Affinity chromatography 24 Purification of His-tagged proteins 25 Purification of GST-tagged proteins 26 Purification of MBP-tagged proteins 26 Low affinity chromatography 26 III. “Common sense” strategy in protein purification 27 General principles and tips in “common sense” strategy 27 Algorithm for development of purification protocol for soluble over expressed protein 29 Brief scheme of purification of soluble protein 36 Timing for refined purification protocol of soluble over -expressed protein 37 DNA-binding proteins 38 IV. Protocols 41 1. Preparation of the stock solutions 41 2. Quick and effective cell disruption and preparation of the cell free extract 42 3. Protamin sulphate (PS) treatment 43 4. Analytical ammonium sulphate cut (AM cut) 43 5. Preparative ammonium sulphate cut 43 6. Precipitation of proteins by ammonium sulphate 44 7. Recovery of protein from the ammonium sulphate precipitate 44 8. Analysis of solubility of expression 45 9. Analysis of expression for low expressed His tagged protein 46 10. Bio-Rad protein assay Sveta’s easy protocol 47 11. -

Western Blotting Guidebook

Western Blotting Guidebook Substrate Substrate Secondary Secondary Antibody Antibody Primary Primary Antibody Antibody Protein A Protein B 1 About Azure Biosystems At Azure Biosystems, we develop easy-to-use, high-performance imaging systems and high-quality reagents for life science research. By bringing a fresh approach to instrument design, technology, and user interface, we move past incremental improvements and go straight to innovations that substantially advance what a scientist can do. And in focusing on getting the highest quality data from these instruments—low backgrounds, sensitive detection, robust quantitation—we’ve created a line of reagents that consistently delivers reproducible results and streamlines workflows. Providing scientists around the globe with high-caliber products for life science research, Azure Biosystems’ innovations open the door to boundless scientific insights. Learn more at azurebiosystems.com. cSeries Imagers Sapphire Ao Absorbance Reagents & Biomolecular Imager Microplate Reader Blotting Accessories Corporate Headquarters 6747 Sierra Court Phone: (925) 307-7127 Please send purchase orders to: Suite A-B (9am–4pm Pacific time) [email protected] Dublin, CA 94568 To dial from outside of the US: For product inquiries, please email USA +1 925 307 7127 [email protected] FAX: (925) 905-1816 www.azurebiosystems.com • [email protected] Copyright © 2018 Azure Biosystems. All rights reserved. The Azure Biosystems logo, Azure Biosystems™, cSeries™, Sapphire™ and Radiance™ are trademarks of Azure Biosystems, Inc. More information about Azure Biosystems intellectual property assets, including patents, trademarks and copyrights, is available at www.azurebiosystems.com or by contacting us by phone or email. All other trademarks are property of their respective owners. -

The Art of Protein Purification

1 The Art of Protein Purification William Ward Rutgers University, New Brunswick NJ, USA 1. Introduction Describing, in words, the details of protein purification to a relative novice in the field is not unlike explaining on paper the steps required to turn a set of colored oils into a beautiful pastoral scene on sheet of stretched canvas. Playing the oboe in a sophisticated metropolitan orchestra or performing a solo aria in a Gilbert & Sullivan operetta are accepted artistic endeavors that command great mastery of technique. Each of these art forms requires years of experience and endless experimentation and refinement of technique. Protein purification is no different. It is an art form. Like all other art forms, perfecting the art of protein purification requires a long apprenticeship. But, like all other art forms, protein purification is aesthetically rewarding to the practitioner. Every day brings new challenges, new insights, new hurdles, and new successes. Art is a process, not a destination. Protein purification fits the same definition. Perfecting the skills of protein purification can take many years of hands-on experience as well as periodic upgrading of those skills. Perhaps the most important part of protein purification is the set of pre-column steps that precede column chromatography. Pre- column steps are not covered as much in the protein purification literature as column chromatography, HPLC, and electrophoresis. So, I have chosen to focus much of my attention on the earlier stages of protein purification. More than column chromatography, pre-column steps are highly diverse and highly creative. Here the artistic aspects of protein purification are most apparent. -

Purification of the Recombinant Green Fluorescent Protein from Tobacco

Dong et al. BMC Biotechnology (2019) 19:86 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12896-019-0590-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Purification of the recombinant green fluorescent protein from tobacco plants using alcohol/salt aqueous two-phase system and hydrophobic interaction chromatography Jie Dong1,2,3, Xiangzhen Ding1,2,3 and Sheng Wang1,2,3* Abstract Background: The green fluorescent protein (GFP) has been regarded as a valuable tool and widely applied as a biomarker in medical applications and diagnostics. A cost-efficient upstream expression system and an inexpensive downstream purification process will meet the demands of the GFP protein with high-purity. Results: The recombinant GFP was transiently expressed in an active form in agoinoculated Nicotiana benthamiana leaves by using Tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) RNA-based overexpression vector (TRBO). The yield of recombinant GFP was up to ~ 60% of total soluble proteins (TSP). Purification of recombinant GFP from the clarified lysate of N. benthaniana leaves was achieved by using an alcohol/salt aqueous two-phase system (ATPS) and following with a further hydrophobic interaction chromatography (HIC). The purification process takes only ~ 4 h and can recover 34.1% of the protein. The purity of purified GFP was more than 95% and there were no changes in its spectroscopic characteristics. Conclusions: The strategy described here combines the advantages of both the economy and efficiency of plant virus-based expression platform and the simplicity and rapidity of environmentally friendly alcohol/salt ATPS. It has a considerable potential for the development of a cost-efficient alternative for production of recombinant GFP. Keywords: Green fluorescent protein, Plant virus, Transient gene expression, Aqueous two-phase system, Hydrophobic interaction chromatography Background Through the application of DNA recombinant technol- Green fluorescent protein (GFP) was originally derived ogy, GFP has successfully been produced by a variety of from jellyfish Aequorea victoria species, which exhibit an hosts [5]. -

Thermo Scientific Pierce Cell Lysis Technical Handbook Version 2

Thermo Scientific Pierce Cell Lysis Technical Handbook Featuring Cell Lysis Reagents and Detergents Version 2 To order, call 800-874-3723 or 815-968-0747. Outside the United States, contact your local branch office or distributor. Table of Contents Thermo Scientific Cell Fractionation Kits 25-37 Subcellular Fractionation Kit 25-26 Mem-PER® Eukaryotic Membrane 27-28 Protein Extraction Kit Mitochondria Isolation Kits 29-31 NE-PER® Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Kit 32-34 Cell Surface Protein Isolation Kit 35 Organelle Enrichment Kits 36-37 DNA Extraction 38 Yeast DNA Extraction Kit 38 Thermo Scientific Lyse and Go™ PCR Reagent 38 Detergents 39-43 Thermo Scientific Pierce Cell Lysis Reagents Introduction to Detergents 39-40 Selection Guide 1 Properties of Common Detergents 40 Thermo Scientific Surfact-Amps and Introduction to Protein Extraction 2-5 Surfact-Pak Detergents 41 Cell Lysis Methods 2-5 Specialized Detergents 41-43 Detergent Removal 43 Introduction to Thermo Scientific Cell Lysis Solutions 6-15 Protease Inhibitors 44-47 ® B-PER Bacterial Protein Extraction Reagents 7-9 Halt™ Protease Inhibitor Single-Use Cocktails 44-45 ® I-PER Insect Cell Protein Extraction Reagent 10 Halt Phosphatase Inhibitor Cocktails 45 ® M-PER Mammalian Protein Extraction Reagent 11 Halt Combined Cocktails 46 ® P-PER Plant Protein Extraction Reagent 12-13 Protein Stabilizing Cocktail 47 ® T-PER Tissue Protein Extraction Reagents 14 PMSF 47 ® Y-PER Yeast Protein Extraction Reagents 15 Soybean Trypsin Inhibitor 47 Buffers 16 Protein Refolding 48-49 RIPA Buffer 16 Pierce Protein Refolding Kit 48 Fusion Protein Purification 17-22 Inclusion Body Solubilization Reagent 49 Fusion Protein Purification Kits 17-22 GST Orientation Kit 22 Mammalian and Yeast β-Gal Kits 23-24 Thermo Scientific Pierce Cell Lysis Reagents Selection Guide Description Organisms/Samples Dialyze1 Compatibility Thermo Scientific Protein Assay Compatibility Notes B-PER Reagent Gram(-) bacteria, S. -

AES Application Focus Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins Page 1

AES Application Focus Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins Page 1 Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins Adapted from Chapter 7, Gel Electrophoresis of Proteins, by David E. Garfin, Pages 197-268, in Essential Cell Biology, Volume 1: Cell Structure, A Practical Approach, Edited by John Davey and Mike Lord, Oxford University Press, Oxford UK (2003). Used by permission of Oxford University Press. At one time or another during the course of protein analysis or purification, researchers are likely to make use of gel electrophoresis. All laboratories working with proteins have some capability for carrying out gel electrophoresis and all researchers have at least rudimentary knowledge of the technique. Gel electrophoresis can provide information about the molecular weights and charges of proteins, the subunit structures of proteins, and the purity of a particular protein preparation. It is relatively simple to use and it is highly reproducible. The most common use of gel electrophoresis is the qualitative analysis of complex mixtures of proteins. Microanalytical methods and sensitive, linear image analysis systems make gel electrophoresis popular for quantitative and preparative purposes as well. The technique provides the highest resolution of all methods available for separating proteins. Polypeptides differing in molecular weight by as little as a few hundreds of daltons and proteins differing by less than 0.1 pH unit in their isoelectric points are routinely resolved in gels. Gel electrophoresis is a broad subject encompassing many different techniques. Sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) is the most commonly practiced gel electrophoresis technique used for proteins. The method provides an easy way to estimate the number of polypeptides in a sample and thus assess the complexity of the sample or the purity of a preparation. -

One-Step Purification of Recombinant Proteins Using a Nanomolar-Affinity Streptavidin-Binding Peptide, the SBP-Tag

Protein Expression and Purification 23, 440±446 (2001) doi:10.1006/prep.2001.1515, available online at http://www.idealibrary.com on One-Step Purification of Recombinant Proteins Using a Nanomolar-Affinity Streptavidin-Binding Peptide, the SBP-Tag Anthony D. Keefe,1 David S. Wilson,2 Burckhard Seelig, and Jack W. Szostak Department of Molecular Biology and Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, Massachusetts 02114 Received May 7, 2001, and in revised form July 20, 2001 Protein affinity tags are widely used for the purifica- We describe the use of the SBP-tag, a new streptavi- tion and detection of recombinant proteins, particularly din-binding peptide, for both the one-step purification from complex mixtures such as lysed cells. However, and the detection of recombinant proteins. The SBP- only a small number of affinity tags are available, and tag sequence is 38 amino acids long and binds to strep- tavidin with an equilibrium dissociation constant of there are significant drawbacks associated with the use 2.5 nM. We demonstrate that a single-step purification of many of them. Commonly used categories of tags, of SBP-tagged proteins from bacterial extract yields and their limitations, are described below: samples that are more pure than those purified using maltose-binding protein or the His-tag. The capacity 1. Fusion protein tags such as maltose-binding pro- of the immobilized streptavidin used to purify SBP- tein (MBP)3 (1) and glutathione S-transferase (2), which tagged proteins is about 0.5 mg per milliliter of matrix, bind to maltose/amylose and glutathione, respectively. -

Size Separation Techniques for the Characterisation of Cross-Linked Casein: a Review of Methods and Their Applications

separations Review Size Separation Techniques for the Characterisation of Cross-Linked Casein: A Review of Methods and Their Applications Norbert Raak 1,*, Raffaele Andrea Abbate 2,3, Albena Lederer 2,3, Harald Rohm 1 and Doris Jaros 1 1 Chair of Food Engineering, Institute of Natural Materials Technology, Technische Universität Dresden, 01062 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] (H.R.); [email protected] (D.J.) 2 Polymer Separation Group, Department of Analytics, Leibniz-Institut für Polymerforschung Dresden e.V., Hohe Straße 6, 01069 Dresden, Germany; [email protected] (R.A.A.); [email protected] (A.L.) 3 Faculty of Mathematics and Science, Technische Universität Dresden, 01062 Dresden, Germany * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +49-351-463-38797 Received: 8 November 2017; Accepted: 8 February 2018; Published: 12 February 2018 Abstract: Casein is the major protein fraction in milk, and its cross-linking has been a topic of scientific interest for many years. Enzymatic cross-linking has huge potential to modify relevant techno-functional properties of casein, whereas non-enzymatic cross-linking occurs naturally during the storage and processing of milk and dairy products. Two size separation techniques were applied for characterisation of these reactions: gel electrophoresis and size exclusion chromatography. This review summarises their separation principles and discusses the outcome of studies on cross-linked casein from the last ~20 years. Both methods, however, show limitations concerning separation range and are applied mainly under denaturing and reducing conditions. In contrast, field flow fractionation has a broad separation range and can be easily applied under native conditions. -

5.2 Protein Purification

Protein purification Purification of a His6-tagged Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) 5.2 Protein purification 5.2.1 Purification of a His6-tagged Green Fluorescent Protein (GFP) Principle You can add either a N- or C-terminal His6-tag to the protein that you want to express if nd you use the RTS pIVEX His6-tag 2 generation vector set (pIVEX2.3d; pIVEX2.4d, see Chapter 2.4.2.1) or the RTS E. coli Linear Template Generation Set, His6-tag (see Chapter 2.3.3.1). These His6-tagged proteins can be purified in one step by immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) (Ford, C. F. et al., 1991) on a nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni- NTA) column. In a single step, this affinity matrix can purify a protein (starting concen- tration less than 1% of the total protein) to more than 95% homogeneity. Nitrilotriacetic acid (NTA) is a tetradentate chelating adsorbent developed by Roche Diagnostics GmbH. NTA occupies four of six ligand binding sites of the nickel ion, leav- ing two sites free for interaction with the His6-tag. NTA binds metal ions tightly, allowing use of stringent washes. Histidine residues on the tag, connected via a short linker to the C- or N-terminus of the protein, bind to the Ni-ions. The protein can be eluted by competitive displacement with 55 imidazole. Note: Since Ni-NTA is not as selective as other affinity chromatography matrices, it may also bind proteins with exposed patches of histidine, cysteine or tryptophan residues. Therefore elution conditions must be optimized for each protein. -

Isolation Purification and Characterization of Protein from Litchi Chinensis Honey and Generation of Peptides

MedDocs Publishers ISSN: 2637-4528 Journal of Addiction and Recovery Open Access | Research Article Isolation, purification and characterization of protein from Litchi chinensis honey and generation of peptides Debalina Bose1; Manchikanti Padmavati2; Rintu Banerjee1,3* 1P.K. Sinha Centre for Bioenergy and Renewables, Advanced Technology Development Centre, Indian Institute of Technology Kharag- pur, India 2Rajiv Gandhi School of Intellectual Property Law, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India 3Agricultural and Food Engineering Department, Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India *Corresponding Author(s): Rintu Banerjee Abstract P.K. Sinha Centre for Bioenergy and Renewables, Objective: Food addiction is an eating disorder affecting Advanced Technology Development Centre, Indian the behavioral and neurological condition associated with Institute of Technology Kharagpur, India BMI (Body mass index), BED (binge eating disorder) and obesity in human being. High-calorie foods, especially sug- Email: [email protected] & [email protected] ar, have an addictive potential. The conventional treatment processes involving cognitive behavioral therapy, mental health treatments and intake of drugs have acute side ef- Received: Dec 19, 2019 fects. The objective of this study was to characterize a high calorie natural food honey, which has been reported to have Accepted: Feb 25, 2020 addictive behavior, and further generate peptides from the Published Online: Mar 02, 2020 protein using enzyme. Journal: Journal of Addiction and Recovery Methods: Protein from honey was concentrated by Publisher: MedDocs Publishers LLC ultrafiltration, purified by ion exchange chromatography, Online edition: http://meddocsonline.org/ characterized by SDS-PAGE, isoelectric focusing, sequencing and identified by MALDI-TOF/MS analysis. Copyright: © Banerjee R (2020). -

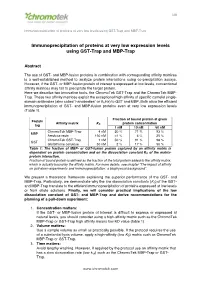

MBP and GST-Traps for Immunoprecipitation of Low

1/8 Immunoprecipitation of proteins at very low levels using GST-Trap and MBP-Trap Immunoprecipitation of proteins at very low expression levels using GST-Trap and MBP-Trap Abstract The use of GST- and MBP-fusion proteins in combination with corresponding affinity matrices is a well-established method to analyze protein interactions using co-precipitation assays. However, if the GST- or MBP-fusion protein of interest is expressed at low levels, conventional affinity matrices may fail to precipitate the target protein. Here we describe two innovative tools, the ChromoTek GST-Trap and the ChromoTek MBP- Trap. These two affinity matrices exploit the exceptional high affinity of specific camelid single- domain antibodies (also called “nanobodies” or VHHs) to GST and MBP. Both allow the efficient immunoprecipitation of GST- and MBP-fusion proteins even at very low expression levels (Table 1). Fraction of bound protein at given Protein Affinity matrix K protein concentration tag D 1 nM 10 nM 50 nM ChromoTek MBP-Trap 4 nM 20 % 71 % 93 % MBP Amylose resin 150 nM <1 % 6 % 25 % ChromoTek GST-Trap 1 nM 50 % 91 % 98 % GST Glutathione cellulose 50 nM 2 % 17 % 50 % Table 1: The fraction of MBP- or GST-fusion protein captured by an affinity matrix is dependent on protein concentration and on the dissociation constant KD of the matrix- protein interaction. Fraction of bound protein is defined as the fraction of the total protein added to the affinity matrix, which is actually bound by the affinity matrix. For more details, see chapter “The impact of affinity on pull-down experiments and immunoprecipitation: a biophysical background”.