The Battersea Power Station: Use and Reuse

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

INVESTOR PACK INTERIM RESULTS for the 6 MONTHS ENDING 30TH JUNE 2018 INVESTOR PACK Introduction to Your Presenters

INVESTOR PACK INTERIM RESULTS FOR THE 6 MONTHS ENDING 30TH JUNE 2018 INVESTOR PACK Introduction to your presenters Mark Lawrence Group Chief Executive Officer Appointed to Board, 2nd May 2003 | Age 50 Mark has had 31 years with the company and started his career here by completing an electrical apprenticeship in 1987. He progressed through the company, becoming Technical Director in 1997, Executive Director in 2003 and Managing Director, London Operations in 2007. As Group Chief Executive Officer since January 2010, Mark has led strategic changes across the group and remains a hands-on leader, taking personal accountability and pride in Clarke's performance and, ultimately our shareholders’ and clients’ satisfaction. He regularly walks project sites and gets involved personally with many of our clients, contractors and our supply chain. Trevor Mitchell Group Finance Director Appointed to the Board on 1st February 2018 | Age 58 Trevor is a Chartered Accountant and accomplished finance professional with extensive experience across many sectors, including financial services, construction and maintenance, education and retail, working with organisations such as Balfour Beatty plc, Kier Group plc, Rok plc, Clerical Medical Group and Halifax plc. Prior to his appointment, Trevor had been working with TClarke since October 2016, assisting with simplifying the structure and improving the Group’s financial controls and procedures. 2 INVESTOR PACK M&E Contracting Every Picture tells a TClarke Story Secured Battersea Power Station Phase 2 Electrical -

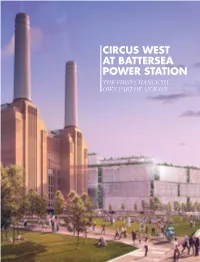

Circus West at Battersea Power Station the First Chance to Own Part of an Icon

CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE FIRST CHANCE TO OWN PART OF AN ICON PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 01 02 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 03 A GLOBAL ICON 04 AN IDEAL LOCATION 06 A PERFECT POSITION 12 A VISIONARY PLACE 14 SPACES IN WHICH PEOPLE WILL FLOURISH 16 AN EXCITING RANGE OF AMENITIES AND ACTIVITIES 18 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION 20 RIVER, PARK OR ICON WHAT’S YOUR VIEW? 22 CIRCUS WEST TYPICAL APARTMENT PLANS AND SPECIFICATION 54 THE PLACEMAKERS PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 1 2 CIRCUS WEST AT BATTERSEA POWER STATION A GLOBAL ICON IN CENTRAL LONDON Battersea Power Station is one of the landmarks. Shortly after its completion world’s most famous buildings and is and commissioning it was described by at the heart of Central London’s most the Observer newspaper as ‘One of the visionary and eagerly anticipated fi nest sights in London’. new development. The development that is now underway Built in the 1930s, and designed by one at Battersea Power Station will transform of Britain’s best 20th century architects, this great industrial monument into Battersea Power Station is one of the centrepiece of London’s greatest London’s most loved and recognisable destination development. PHASE 1 APARTMENTS 3 An ideal LOCATION LONDON The Power Station was sited very carefully a ten minute walk. Battersea Park and when it was built. It was needed close to Battersea Station are next door, providing the centre, but had to be right on the river. frequent rail access to Victoria Station. It was to be very accessible, but not part of London’s congestion. -

CIRCUS WEST VILLAGE – Designed by Drmm and Simpsonhaugh and Partners – BPSDC Office Headquarters – 865 New Homes – 23 Cafés, Restaurants and Shops

LIVE DON’T DO ORDINARY CGI of Battersea Power Station looking towards Battersea Park Battersea Power Station is a global icon, in one BATTERSEA POWER STATION of the world’s greatest cities. The Power Station’s incredible rebirth will see it transformed into one of the most exciting and innovative new neighbourhoods in the world, comprising unique homes designed YOUR HOME IN A by internationally renowned architects, set amidst the best shops, restaurants, offices, green space, GLOBAL ICON and spaces for the arts. 2 3 Battersea Power Station’s place in history is assured. From its very beginning, the building’s titanic form and scale THE ICON have captured the world’s imagination. Two design icons, one designer. The world-renowned London telephone box was one of architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s most memorable creations, the other was Battersea Power Station. Red buses, A BRITISH ICON Beefeaters, Buckingham Palace, Big Ben and Battersea Power Station – this icon takes its place as part of the world’s visual language for London. 4 5 BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE ICON A DESIGN ICON This was no ordinary Power Station, no ordinary design. Entering through bronze doors sculpted with personifications of power and energy, ascending via elaborate wrought iron staircases and arriving at the celebrated art deco control room with walls lined with Italian marble, polished parquet flooring and intricate glazed ceilings, looking out across the heart of the Power Station, its turbine hall, its giant walls of polished terracotta, it’s no wonder it was christened the ‘Temple of Modern Power’. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design of Battersea Power Station turned this immense structure into a thing of beauty, which stood as London’s tallest building for 30 years and remains one of the largest brick buildings in the world. -

The Power Station

LIVE DON’T DO ORDINARY Battersea Power Station is a global icon, in one BATTERSEA POWER STATION of the world’s greatest cities. The Power Station’s incredible rebirth will see it transformed into one of the most exciting and innovative new neighbourhoods in the world, comprising unique homes designed YOUR HOME IN A by internationally renowned architects, set amidst the best shops, restaurants, offices, green space, GLOBAL ICON and spaces for the arts. 4 5 Battersea Power Station’s place in history is assured. From its very beginning, the building’s titan form and scale THE ICON has captured the world’s imagination. Two design icons, one designer. The world-renowned London telephone box was one of architect Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s most memorable creations, the other was Battersea Power Station. Red buses, A BRITISH ICON Beefeaters, Buckingham Palace, Big Ben and Battersea Power Station – this icon takes its place as part of the world’s visual language for London. 6 7 BATTERSEA POWER STATION THE ICON A DESIGN ICON This was no ordinary Power Station, no ordinary design. Entering through bronze doors sculpted with personifications of power and energy, ascending via elaborate wrought iron staircases and arriving at the celebrated art deco control room with walls lined with Italian marble, polished parquet flooring and intricate glazed ceilings, looking out across the heart of the Power Station, its turbine hall, its giant walls of polished terracotta, it’s no wonder it was christened the ‘Temple of Modern Power’. Sir Giles Gilbert Scott’s design of Battersea Power Station turned this immense structure into a thing of beauty, which stood as London’s tallest building for 30 years and remains one of the largest brick buildings in the world. -

Ekspan T-Mat Expansion Joint Installations

Head Office, UK & Export Sales Ekspan Limited Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Tel: +44 (0) 114 2611126 Fax: +44 (0) 114 2611165 Email: [email protected] Website: www.ekspan.com Ekspan T-Mat Expansion Joint Installations Case Studies Carriageway/Vehicular Traffic Specific Jacksons Port of Dover – 2017 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joints installed at Port of Dover, during lane closures. Skanska St Ives Viaduct - 2017 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joints installed on St Ives Viaduct, Cambridge, during full night closures. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. Reg. 02564540 VAT Reg. 599-8691-41-000 BAM Nuttall Tower Bridge - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 30 Expansion Joints installed on the Tower Bridge refurbishment Project, London. Skanska Battersea Power Station - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joint installed on Halo Bridge - Batersea Power Station project, London. PJ Careys Selfridges London – 2015 Ekspan T-Mat 80 Expansion Joint and upstand installed at Selfridges, London. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. Reg. 02564540 VAT Reg. 599-8691-41-000 SEGRO Heathrow X2 Hatton Cross – 2015 UnderEkspan Railway T-Mat 30 expansionBallast Specificjoint installed on X2 Hatton Cross, London Under Railway Ballast Specific Walsh Group Crum Creek, Philadelphia - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 260 Expansion Joint installed on the Crum Creek Project, Philadelphia. Morgan Sindall A6 Hazel Grove Bridge - 2016 Ekspan T-Mat 130 Expansion Joint and upstand installed on A6 Hazel Grove Bridge, Stockport. Registered in England: Registered Office: Compass Works, 410 Brightside Lane, Sheffield S9 2SP Co. -

NICHOLAS TURNER PARTNER London

NICHOLAS TURNER PARTNER London Based in London, Nick is a real estate partner focussing on commercial property. +44 20 7466 +44 780 920 0665 2640 [email protected] linkedin.com/in/nick-turner-8777a513 KEY SERVICES KEY SECTORS Major Leasing Real Estate Real Estate Infrastructure EXPERIENCE Nick brings over two decades of experience to clients on all aspects of commercial property, including development and investment work. Nick has a particular focus on joint venture transactions and high-value mixed-use development work, including pre-letting and letting work for developers and tenants. Nick is focused on delivering strong commercial outcomes and has developed close relationships with many of the firm's key clients. Nick is the head of the firm’s 'corporate occupation' practice and he has been involved in some of the UK's largest high-value pre-letting transactions. Nick also focuses on the rail sector particularly on developments interacting wtith rail and underground assets. Nick's expertise in commercial property is highlighted by his recommendations in Chambers Global and Legal 500 UK. Nick's experience includes advising: Bluebutton Properties, a jv owning the Broadgate Estate in the City of London, on its major developments and pre-letting deals at 100 Liverpool Street, 135 Bishopsgate, 155 Bishopsgate and Broadwalk House. Tenants signed up include: SMBC, Millbanks, Bank of Montreal, Peel Hunt, TP ICap, McCann-Erickson, Eataly and Monzo Transport for London on its new head offices relocation to the International Quarter, Stratford, a development by a joint venture between Lend lease and LCR; the Northern Line Extension at Battersea Power Station; Crossrail overstation developments at Davies Street and Holborn and development agreements relating to Paddington, Holborn, London Bridge and Knightsbridge underground stations Canada Pension Plan Investment Board on its joint ventures and mixed-use developments with BT Pension Fund at Paradise Circus, Birmingham and Wellington Place, Leeds, both UK Canary Wharf Group on major lettings at one Canada Square. -

Pe1338 Wv Brochure-34.Pdf

Computer generated artist impression Take the next step in your London life and purchase a home at West View Battersea – a superb new collection of apartments, moments from Battersea Park, that offers you a peaceful and luxurious haven from the bustle of the city. On the doorstep of central London, West View Battersea at Berkeley's Vista Chelsea Bridge provides beautiful landscaped courtyards, luxurious interiors, and a building by world-leading architects Scott Brownrigg – all in one of the capital's most desirable riverside neighbourhoods. With Chelsea, Westminster and the iconic Battersea Power Station nearby, West View Battersea will open up a new chapter in urban living – in one of the greatest cities in the world. A NEW PERSPECTIVE Computer generated artist impression A NEW PANORAMA A new perspective to London-living 7 Computer generated artist impression 1 4 7 q West View Battersea River Thames Westminster The Shard 2 5 8 w Battersea Park Chelsea Bridge London Eye Canary Wharf 3 6 9 e Battersea Power Station Victoria Station The City Tate Britain 8 A NEW LANDSCAPE Be part of the evolution With evocative Victorian architecture, fashionable restaurants and bars, and one of the most renowned parks in London, Battersea is fast becoming an exclusive location. A rare corner of grandeur on the Thames, the area is well known for its iconic Battersea Power Station and stunning riverside views. With a wave of new investment in Nine Elms and a new Northern line Underground station, Battersea is also now one of the most sought-after areas in London. West View Battersea is a new part of Wandsworth’s story – an outstanding collection of properties that opens up the possibilities of city-living. -

Unit 11, Linford Street, Battersea, London, Sw8 4Un 1,875 Sq Ft (174 Sq M)

UNIT 11, LINFORD STREET, BATTERSEA, LONDON, SW8 4UN 1,875 SQ FT (174 SQ M) geraldeve.com BBC The Wallace Lincoln’s Collection Inn Fields Location Rateable Value Selfridges St Paul’s Cathedral Bank of England 30 St Mary Axe Mansion House The arch is located on Linford Street Business Estate, a secure £29,750 Royal Opera House Somerset House estate accessed via Stewarts Road, off Wandsworth Road. The National Gallery National Hyde Park Tower of London Theatre Tate Modern EPC Southbank Centre The surrounding area is occupied by a variety of users that are Available on request. City Hall Tower Bridge Green Park London Eye St James’s Park predominantly industrial, trade counter and residential. Businesses Buckingham Palace Royal Albert Hall Palace of Westminster on the estate include Madeira Patisserie, Crosstown Doughnuts Rent Science Museum Harrods Westminster Abbey London South Bank University and Wild and Heart Florists. On application. V&A Westminster Cathedral Imperial War Museum Description Service Charge The unit offers high quality industrial accommodation, with A service charge is applicable for maintenance and repair of the access via an electric up and over roller shutter with separate common areas. The Oval pedestrian access. There is full lining throughout, concrete flooring Battersea Power Station and fluorescent strip lighting. There are also WC and kitchenette Terms facilities in place. A new lease is available by arrangement. Further details available Battersea Park from Gerald Eve LLP. Unit 3, Linford Street, London Specification • 3.6m to eaves (3.7m to apex) Legal Costs • Electric shutter door Each party to bear their own costs. -

Whletheer at East Ham Anid West

THU BlRatim 835 MAY 4, 19291 3MEDICAL NOTES IN PARLIAMENT. LMEDICAL JOUVNA& I a replied that hie understood that was for researchi only, wherieas, according to tlle genier al opinion, the nleed for more JiNtebfrat peltsz itnt Vardiam researchl. Dr. FREMANTLE retorted the the Committee of lhad " [FROM OUR P1ARLIAMENTAr-Y CORRESPONDENT.] Civil Researelh the d research." lIe asserted that the Canicer Campaigni lhad appealed radium, that they had a large stock in lhanid, aind they w4re therefore dissolved Thlis week House was PAITIAMENT will be neXt week. tlhe the proper body to do wlhat the Comrnittee of -Commons the and Civil Fremantle considered Finiance Researelh. Mr. CHAMBERLAIN said mistakeni estimates, and botlh Houses were occupied with the final stages if hie tlhouglht that tlhe wlhole of the recommendations the of bills previously discussed. Committee dealt with researchl. He nio need givinig the At the House of Commons, on April 29tlh, withl Fremantle House of Commonis ani dpportuniity the question ascllairman, Conservative members enltertainied MNIr. Chamberlain an appeal was ma(le, and adlded thlat lhe lhad easoni to and Sir Kingsley Wood dinner. suppose this appeal would be before the General Election. Aniswerinig Mr. Rober t Morri-isoni, CHAMBERLAIN tle committee of. the Comnmittee- of Research niot in- a Local Government (Scotland) positioni to secure aniy guaranitee that rcadiumni boughb Thiird Rcading inz the Houisc Lords. thlrougl a single agenicy would be clheaper than smaller amounits bought by nunuerous purchasers, but opiniion cu Tue I{oise of Lords,o01 April 24thi, read tlhe Governmenit this point, witlh reasonis, 'was set in their (Scotlanid) Bill a third time after makilg mieor amendments r'eport. -

Battersea Power Station

RETAIL & LEISURE CENTRAL LONDON LOCATION THE SHARD THE GHERKIN ST. PAUL’S CATHEDRAL LONDON EYE TRAFALGAR SQUARE WESTMINSTER ABBEY HOUSES OF PARLIAMENT TATE BRITAIN VAUXHALL BRIDGE US EMBASSY BATTERSEA POWER STATION BATTERSEA POWER STATION CHELSEA BRIDGE BATTERSEA PARK BATTERSEA CENTRAL LONDON PARK STATION NINE ELMS VAUXHALL ONE NINE SQUARE WATERLOO ELMS AYKON THE KEYBRIDGE DUMONT THE NINE ELMS CORNICHE VAUXHALL POINT NEWPORT SKY US GARDENS PIMLICO STREET EMBASSY GALLERY VICTORIA NINE ELMS RIVERLIGHT SQUARE NINE ELMS THE NINE ELMS RESIDENCES GROVE BATTERSEA EMBASSY POWER STATION GARDENS LINEAR NEW COVENT NINE ELMS GARDENS GARDEN MARKET PARKSIDE DORLING KINDERSLEY, PENGUIN NINE ELMS RANDOM HOUSE APPLE GARDENS NO18 BATTERSEA POWER STATION / Circa 505 0 aaccrees / 255,0,000 new homese / 500,00000 newe rese idenents / 30,00000 newe woro kersrs / 3.3.1m1m sq ftt of ofofficfi e sppacace Euston Farringdon Warren Street Square Liverpool 20 Barbican MINS Street Regent’s Park Russell 20 MINS CONNECTIVITY Goodge Square on ne Street Bayswater Tottenham Court Road 1 Moorgate 16 13 MINS MINS Marble Arch Bond Oxford Circus Holborn Chancery Lane East White Nottingting SStreettree HIGHLY Acton City HiHill Gate Bank 1 Aldgat Covent Garden Lancaster HolHolland Queensway Gate Green Park St Paul’s Park Leicester Square 12 Wood Lane 13 MINS Hyde Park Corner MINS Piccadilly Cannon Street CONNECTED Shepherd’s High Street Kensington Circus Monument Tower Bush Market Kensington Hill (Olympia) 10 Mansion House Knightsbridge Charing MINS Goldhawk Roadd Cross Blackfriars -

Tall Buildings URBAN DESIGN GROUP URBAN

Summer 2016 Urban Design Group Journal 13UR 9 BAN ISSN 1750 712X DESIGN TALL BUILDINGS URBAN DESIGN GROUP URBAN DESIGN GROUP NewsUDG NEWS more than this, with people being seen col- Nottingham and Bristol respectively. VIEW FROM THE lectively because of their ‘social values and Noha Nasser and the awards panel CHAIR responsibilities’. As urban designers we are for• continuing to grow the Urban Design members of a community. We share similar Awards. values and take on the duty of improving the Ben van Bruggen and Amanda Reynolds quality of life for people who live and work for• their ongoing stewardship of the Recog- in cities, towns and villages. nised Practitioner scheme. This is the last View from the Chair that I will I would like to use this last article to Barry Sellers for providing oral evidence write for Urban Design and it gives me an thank people within the Urban Design Group on• the Urban Design Group's behalf at the opportunity to reflect on the last two years community for continuing to strive to raise House of Lords' Built Environment Select of my tenure. The time has flown by! the standards in urban design practice. Lack Committee. At last March’s National Urban Design of space precludes me from mentioning The various regional conveners of events, Awards I pondered with Graham Smith, a everyone but the list includes the following particularly• Paul Reynolds and Philip Cave former lecturer at Oxford Brookes Universi- members of the community: in London; Peter Frankum in Southampton; ty, the use of the word ‘community’ for new Robert Huxford and Kathleen Lucey for Mark Foster and Hannah Harkis in Manches- developments. -

To View Our Cathodic Protection Brochure

HISTORIC STRUCTURES Cathodic Protection – Design, Installation and Monitoring Battersea Power Station Grosvenor House Apartments Selfridges The Technology Centre provides first class expertise in Historic Structures. Battersea Power Station This project was undertaken with Stonewest Ltd, through which we have developed an excellent working relationship. Between 2003 and 2005 VINCI Construction UK’s Technology Since this time Technology Centre and Stonewest have been Centre (formerly Taywood Engineering Ltd) were responsible involved in several historic building projects, including further for a structural investigation and corrosion condition investigations and refurbishments to the 1st floor cill details assessment of Battersea Power station. These investigations at Selfridges in 2012. included both the reinforced concrete chimneys and the masonry clad steel-framed structures. The work was carried Recommendations out to assess the rate of corrosion and the condition of the “The Department of Environment Transport and Regions steel elements, and to determine existing structural detail. research that Taylor Woodrow has undertaken demonstrates The work also involved a cathodic protection feasibility trial. how modern technology can be used to develop sympathetic repair techniques and preventative maintenance consistent with Grosvenor House Apartments, London English Heritage’s strategy on conservation. We very much support this research.” Since 2004, Technology Centre have been involved in John Fiddler, Head of Architectural Conservation English Heritage. the cathodic protection of the steel frame of Grosvenor House’s South Block. This structure is the largest brick-clad “VINCI’s Technology Centre have worked with us on several different projects relating to the preservation of the historic early twentieth century building in Europe to have been facades of Waterloo House in Birmingham.