1 Does Combined Osteopenia/Osteoporosis And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Sarcopenic Obesity and Its Temporal Associations With

Sarcopenic Obesity and its Temporal Associations with Changes in Bone Mineral Density, Incident Falls and Fractures in Older Men: The Concord Health and Ageing in Men Project 1,2 3 4,5,6 5 5 David Scott , Markus Seibel , Robert Cumming Vasi Naganathan , Fiona Blyth , David G Le Couteur7, David J Handelsman8, Louise M Waite5, Vasant Hirani 5,9 Affiliations: 1 School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, Monash University, Clayton, Victoria, Australia 2 Department of Medicine and Australian Institute of Musculoskeletal Science, Melbourne Medical School – Western Campus, The University of Melbourne, St Albans, Victoria, Australia 3 Bone Research Program, ANZAC Research Institute, and Dept of Endocrinology & Metabolism, Concord Hospital, The University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 4 School of Public Health, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 5 Centre for Education and Research on Ageing, Concord Hospital, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 6 The ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 7 ANZAC Research Institute & Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 8 Department of Andrology, Concord Hospital & ANZAC Research Institute, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 9 School of Life and Environmental Sciences, Charles Perkins Centre, University of Sydney, New South Wales, Sydney, Australia. 1 Conflicts of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest. Corresponding Author: Dr. David Scott School of Clinical Sciences at Monash Health, Monash University Clayton, Victoria, Australia 3168 Email: [email protected] Telephone: +61 3 8572 2397 Fax: +61 3 9594 6437 Abstract Body composition and muscle function have important implications for falls and fractures in older adults. -

ANZBMS Newsletter July 2020

Issue 1, July 2020 ANZBMS Newsletter Wel come t o t he new ANZBMS newsl et t er ANZBMS Annual Scient ific Meet ing goes virt ual Member recognised in Queen's Birt hday Honours How t o connect on Tw it t er Meet our newest members Cover im age: Magnet ic resonance im age of a hum an knee joint Court esy of Feng Pan, Universit y of Tasm ania 1 Welcome to the new ANZBMS Newsletter Over the past year, ANZBMS members have expressed their wishes for greater communication and dissemination of information to members and our wider community. The role of the communications committee is to oversee the delivery of information among members of the ANZBMS and between ANZBMS council and members of the society, by a number of activities. This year, the Communications committee was established to include one member from each of the ANZBMS subcommittees in addition to our ordinary members and the ANZBMS Honorary Secretary (See pg.11 for more details). One area ANZBMS members expressed that they would like to see improved was In this issue the general newsletter to members. This need was further increased by the current COVID-19 pandemic, which has changed the way we work and interact with others. It is important for us to be able to connect to each other and share our experiences, particularly as we will not be able to gather in person this year. Inspired by the high-quality newsletter generated by our Early Career Investigators (ECI), we have adopted a similar approach and will be releasing issues on a quarterly basis. -

Brotherhood of BROTHERHOOD St Laurence and Community Aid Abroad of S! LAURENCE Heiping Peopte David Scott Buitd Better Iives He Got Things Done

A memoir of Gerard Kennedy Tucker, Angiican priest, founder of the Brotherhood of BROTHERHOOD st Laurence and Community Aid Abroad of S! LAURENCE Heiping peopte David Scott buitd better iives He got things done a memoir of Gerard Kennedy Tucker, Angiican priest, founder of The Brotherhood of St Laurence and Community Aid Abroad David Scott 'Not everyone who says to me, Lord, Lord shalt enter the kingdom of heaven but he that doeth the wilt of my Father' Matthew 7:21. First published in November 2000 by the Brotherhood of St Laurence 67 Brunswick Street Fitzroy VIC 3065 Telephone (03) 9483 1183 www.bsl.org.au Scott, David He got things done: a memoir of Gerard Kennedy Tucker, Anglican Priest, founder of The Brotherhood of St Laurence and Community Aid Abroad ISBN 1-876250-40-2 @ Brotherhood of St Laurence, 2000 This book is copyright. Apart from fair dealing for the purpose of private study, research, criticism, or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries should be addressed to the publisher. C o f e /? f s Introduction 1 Early life 7 After the war 15 A personal reflection 21 Notes 33 //7ff0(y;vCf/0/7 In the early light at 6.30 am on 7 November 1944, two Anglican priests, Gerard Kennedy Tucker and Frank Coaldrake, and welfare officer Tony Bishop occupied the verandah of a house in St James Road in the Melbourne suburb of Armadale. They would remain, they said, until the sub-tenant vacated to allow the ill, 85-year-old owner to spend her last days in her own home. -

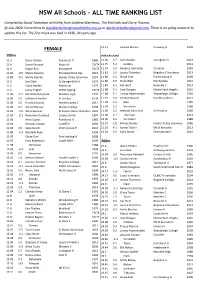

NSW All Schools - ALL TIME RANKING LIST

NSW All Schools - ALL TIME RANKING LIST Compiled by David Tarbotton with help from Andrew Matthews, Tim McGrath and Gerry Thomas. @ July 2020. Corrections to [email protected] or [email protected]. There is on going research to update this list. The first meet was held in 1936, 84 years ago. ____________________________________________________________________________________________________ 12.11 Jacquie Munro Irrawang H 1999 FEMALE 100m Wind Assisted 11.3 Diane Holden Peakhurst H 1980 11.66 4.7 Sam Geddes Caringhan H 2013 11.4 Kerrie Pearson Kotara H 73/74 11.75 5.2 Geddes 2013 11.5 Robyn Ellis Kirrawee H 76/77 11.75 2.6 Rebecca Vormister Corrimal 1991 11.81 -0.9 Maisie Stevens Kincoppal Rose Bay 2016 11.82 3.0 Jessica Thornton Brigidine C Randwick 2013 11.83 -0.1 Mindy Slomka Hunter Valley Grammar 1997 11.86 3.1 Eloise Graf Port Hacking H 2009 11.6 Sue Clark St George Girls H 1979 11.86 2.6 Fiona Blair PLC Pymble 1991 11.6 Diane Holden Peakhurst 1979 11.87 4.1 Kat Hunt Roseville C 2013 11.6 Jenny English OLMC Epping 73/74 11.88 5.1 Sara Dougan Monte Saint Angelo 2016 11.85 -0.1 Michelle Dalrymple Maclean High 1997 11.88 3.1 Larissa Pasternatsky Abbotsleigh College 2009 11.85 1.0 Catherine Horder St Ursulas 1993 11.91 3.2 Kristie Edwards Pymble Ladies C 2017 11.89 0.2 Kristie Edwards Pymble Ladies C 2017 11.94 2.6 Blair 1989 11.90 0.4 Rachel Massey Marian College 1993 11.98 2.2 Vormister 1988 11.91 -1.0 Alicia Spencer St Francis Xavier Hamilton 2001 11.98 2.2 Melinda Gainsford St Vincents 1989 11.93 -0.1 Rosemary -

View Program

1 EMCR COMMITTEE CHAIR’S WELCOME On behalf of the organising committee, it is my pleasure to welcome you to the ANZSSFR World Sarcopenia Day Symposium presented by the Early- and Mid-Career Researchers and clinicians (EMCR) committee. The 4th of July is World Sarcopenia Day and therefore we dedicated this symposium to highlight this special day. We have an exciting online program including presentations from EMCRs across the world and the outcomes of the Delphi Process on Sarcopenia Diagnosis and Management, led by EMCRs David Scott and Jesse Zanker. The aim of the EMCR Committee is to promote, support and engage with as many EMCRs as possible to shape the future generation of sarcopenia and frailty research. Therefore, we have 12 short presentations by EMCRs showcasing their research. We have asked the presenters to include their contact details on their slides to encourage the audience to contact the presenters to learn more about their research and encourage networking and collaboration opportunities. Please take this opportunity to be in contact with the next generation! The Sarcopenia and Diagnosis Management Task Force was established by the EMCRs David Scott and Jesse Zanker. During this symposium, the outcomes of the Delphi process will be shared for the first time. This is an important step to standardise sarcopenia diagnosis and management across Australia and New Zealand. We hope to see experts and consumers attending this symposium who participated in this Delphi process, as their input was valuable to the outcomes. We also hope that the outcomes can be implemented into research and clinical practice in Australia and New Zealand. -

Castle 550 Trailer Sailer

Richmond River Sailing and Rowing Club website: www.rrsrc.com.au P.O. Box 963 Ballina 2478 Commodore Phill Robbins Club Newsletter 27/11/19 0466668541 Vice Commodore Jonathan Horsley POST - HARWOOD MINI NEWSLETTER 0412798505 Rear Commodore Chris Hallett 0414866998 Secretary Nola Hallett 0414866999 Treasurer Col Woodbury Class Reps Gennakers – Michael Wiley Catamarans – Michael Cocks Trailers – Paul Morris Monos – Graham Hams Rowing Officer Graham Hams Website Admin Mark Pierce Publicity Officer Trent Morgan Training Club Committee ALL EMAIL CORRESPONDENCE TO: [email protected] CONTENTS 2. Race Reports 5. Upcoming Away Events 7. Marketplace THAT’S HARWOOD!!! A couple of reports from last weekend’s smoky Harwood Regatta inside… 1 Richmond River Sailing and Rowing Club website: www.rrsrc.com.au P.O. Box 963 Ballina 2478 RS100’s 23-24 November 2019 (thanks Duncan – Ed) Seven RS100’s attended the inaugural RS100 NSW state championships at Harwood on the weekend of 23- 24 November 2019. Reining national champion David Williamson drove up from Melbourne with his own boat, plus a second that RRSRC’s David Scott had just bought. The rest of the RS100 team from RRSRC and Paul Greer from Lake Wivenhoe were able to get through the fire zone at New Italy ready for Saturday’s Race 1, in a 20-knot nor-easter. Vince was sporting a new mainsail but lost it out of the mast track. Garry and Paul also DNF-ed. David Scott raced home before the fire closed the Highway (yet again) and made it to a compulsory family event. Meanwhile, three boats continued up the Clarence River towards Iluka. -

Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease

11th edition of Clinical Trials on Alzheimer's Disease LATE CALL FOR ABSTRACTS September 1-10, 2018 www.ctad-alzheimer.com Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute CTAD 2018 BARCELONA, SPAIN Organizing and Scientific Committees p. 3 Program ........................................................................ p. 4 Wednesday, October 24 ................................... p. 4 Thursday, October 25 ................................... p. 5 Friday, October 26 ................................... p. 8 Saturday, October 27 ................................... p. 11 Registration / Accommodations ............. p. 14 design by laura frère - photo credit : istock photo - adobe stock CTAD Organizing Committee Jacques Touchon MD, PhD Paul Aisen MD University Alzheimer’s Hospital of Montpellier Therapeutic Research Institute (ATRI) France University of Southern California (USC), San Diego, USA Bruno Vellas MD, PhD Mike Weiner MD University University of California Hospital of Toulouse San Francisco (UCSF) France USA CTAD Scientific Committee Susan ABUSHAKRA (San Francisco) Constantine G. LYKETSOS (Baltimore) Paul AISEN (San Diego) José Luis MOLINUEVO (Barcelona) Kaj BLENNOW (Molndal) Jean-Marc ORGOGOZO (Bordeaux) Merce BOADA (Barcelona) Ronald PETERSEN (Minnesota) Maria CARRILLO (Chicago) Craig W. RITCHIE (Edinburgh) Mony John DE LEON (New York) Augustin RUIZ (Barcelona) Steven DEKOSKY (Miami) Robert RISSMAN (San Diego) Rachelle DOODY (Basel) Stephen SALLOWAY (Providence) Bruno DUBOIS (Paris) Rachel SCHINDLER (New York) Howard FELDMAN (Vancouver) -

Four Early French Teachers at the University of Sydney*

FOUR EARLY FRENCH TEACHERS AT THE UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY* By MARGARET KERR THE men who taught French at Sydney University in the years 1854 to 1886, as well as illustrating by their careers the problems and uncertainties of an era in modern language teaching in universities, constituted in themselves a remarkable variety of human types. They could even be given labels, such as "the scholar", "the debrouillaTd", "the confidence-man", and "the honest work horse". Perhaps that would be somewhat unjust: their real contribution cannot be summed up so easily. There is no doubt that most of the work done in French in these early years was of a low standard and that the teaching of this subject within a university was difficult to justify. Some such assertion as this would also apply to any British university of the period. However, repeated statements by the Sydney University authorities showed that they were well aware of the short comings of modern language studies in the University. They tried various changes, but none proved satisfactory. Then, early in the 80s, after hearing the news of the Challis bequest,! the Sydney University Senate decided to reorganize completely the teaching of modern languages by appointing a Professor of Modern Literature, and by combining the modern subjects English, French and German into one Department under his direction. This change was effected between the years 1887 and 1889 with the appointment of Mungo William MacCallum to the Chair, the creation of the Department of Modern Literature, and the arrival in 1889 of Dr Emil J. Trechmann, appointed Lecturer in French and German. -

NSW Schoolboys' Teams 1973

NSW Schoolboys’ Teams 1973 - 2019 1973 Adelaide 1974 Sydney/Newcastle Ian Stone Wallsend HS Don Smith Cardiff HS Ian Stone Wallsend HS David Storey Jesmond HS John J. Turnbull Kurri Kurri HS Joe Senkalski Jesmond HS Brian Dodd Oak Flats HS Tim O’May Granville Boys HS John Cowburn Booragul HS Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1975 1976 Joe Senkalski Jesmond HS Tom Vukovich Birrong Boys HS R. Yousiph Holroyd HS W. Parker Drummoyne Boys HS Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1977 (NSW) 1977 (NNSW) Tony Pezzano Canterbury Boys HS Peter Tredinnick Booragul HS Alan Robertson North Sydney Boys HS Ross Lawrence Wallsend HS Peter Katholos Peter Hill Ray Boulter Wyong HS Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1978 (NSW) 1978 (NNSW) George Chapman Malcom McClelland David Smith Michael Boogaard Tom Vukovich David Brenton Peter Wilson P. Dolton Bankstown Boys HS Peter Raskopoulos Paul Kay Greg Woodhouse Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1979 (NSW) 1979 (NNSW) Ian Watson Garry Phillips David Smith Howard Tredinnick Booragul HS Marcel Radojevic Brett Bevis David Skeen Robert Wheatley Peter Raack Grant Lee Peter Vale S. Collins North Sydney Boys HS D.Wilcock Epping Boys HS Daryl Gooch Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1980 Frank Casacchia John Pettas Garry Phillips Marcel Radojevic Coach: Manager: 1981 1982 Bob Catlin Ray Vliestra Zivko Hristovski Garry Phillips Louis Dounis Lenny Vial Coach: Coach: Manager: Manager: 1983 1984 Alex Bundalo Geoff Gunning Geoff Biscaya Martin Drienne Matthew Garland Wyong High School Paul Foster Bill Londos Nicholas Conradi Nick Papas -

The DS Mitchell Story’ Exhibition Mitchell Library Centenary Celebration

Supported by Message from Her Excellency, Professor Marie Bashir AC CVO ‘A Grand Obsession: The DS Mitchell Story’ Exhibition Mitchell Library Centenary Celebration I want to record my profound appreciation to David Scott Mitchell for his bequest to the State Library of New South Wales 100 years ago, of a priceless collection of 40,000 books, manuscripts, maps and pictures, as well as an endowment of £70,000. The importance of the DS Mitchell Bequest to our state, to our nation, and even beyond, is incalculable. The documents initially comprising the bequest, together with historical acquisitions subsequently acquired through his generosity, have provided a glorious legacy of the Australian spirit and identity. I have always said that, if ordered in the most catastrophic of times imaginable, in fantasy, to save just one man-made structure in Australia from destruction, I would immediately nominate the Mitchell Library with all its contents. There are no words which could adequately record our indebtedness and gratitude for this priceless gift. Marie R Bashir AC CVO Governor of New South Wales A GRAND OBSESSION: THE DS MITCHELL STORY v Foreword David Scott Mitchell (1836–1907) was Australia’s greatest book collector. He accumulated the world’s pre-eminent collection of books, manuscripts, maps and pictures relating to Australia and the Pacific. On his death in July 1907, his collection was bequeathed to the Public (now State) Library of New South Wales, together with an endowment of £70,000 to fund additions to his collection. The conditions of the bequest were that his collection should be housed separately and known as the Mitchell Library and should be freely available on conditions similar to those in force in the British Museum library, now the British Library. -

In Service of Their Country

In service of their country On Wednesday 7 March 2007, response capacity to the region following Garuda Airline flight GA200 crashed the plane crash. on landing in Yogyakarta, Indonesia. A Disaster Victim Identification (DVI) team Federal Agent Mark Scott and was sent to Yogyakarta to assist with the Commander Brice Steele were among investigation of the disaster and an Air the 21 passengers who died as a result Safety Bureau of Investigation expert of the crash. accompanied the team to assist with he two federal agents were travelling investigations. as part of an advance team ahead of the On Saturday 10 March, DVI experts visit of Foreign Affairs Minister Alexander presented evidence to the Indonesian Downer. hree other Australians including a Identification Board and the Board diplomat, a journalist and an AusAid official subsequently positively identified Federal Agents Brice Steele and Mark Scott and all also lost their lives in this tragedy. Hartigan – Brian of the Australian victims. he following pages are dedicated to the respects. he ceremony was attended by families of Mark and Brice as well as their In a media statement, Commissioner a host of dignitaries including Governor- colleagues, especially in Indonesia and Keelty said while the loss of these two General Michael Jeffery, Deputy Prime agents was deeply felt by all members of in the words of Commissioner Keelty ‘to Minister Mark Vaile, Foreign Affairs Minister the AFP, he hoped that the confirmation celebrate the lives and careers of two great Alexander Downer, Senator Ellison, the could help begin the healing process for members of the AFP’. -

To View a Century Downtown: Sydney University Law School's First

CENTURY DOWN TOWN Sydney University Law School’s First Hundred Years Edited by John and Judy Mackinolty Sydney University Law School ® 1991 by the Sydney University Law School This book is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of study, research, criticism, review, or as otherwise permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Typeset, printed & bound by Southwood Press Pty Limited 80-92 Chapel Street, Marrickville, NSW For the publisher Sydney University Law School Phillip Street, Sydney ISBN 0 909777 22 5 Preface 1990 marks the Centenary of the Law School. Technically the Centenary of the Faculty of Law occurred in 1957, 100 years after the Faculty was formally established by the new University. In that sense, Sydney joins Melbourne as the two oldest law faculties in Australia. But, even less than the law itself, a law school is not just words on paper; it is people relating to each other, students and their teachers. Effectively the Faculty began its teaching existence in 1890. In that year the first full time Professor, Pitt Cobbett was appointed. Thus, and appropriately, the Law School celebrated its centenary in 1990, 33 years after the Faculty might have done. In addition to a formal structure, a law school needs a substantial one, stone, bricks and mortar in better architectural days, but if pressed to it, pre-stressed concrete. In its first century, as these chapters recount, the School was rather peripatetic — as if on circuit around Phillip Street.