Chapter 13 Hells Canyon Complex

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter 18 Southwest Idaho

Chapter: 18 State(s): Idaho Recovery Unit Name: Southwest Idaho Region 1 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate reasonable actions that are believed necessary to recover and/or protect the species. Recovery plans are prepared by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and, in this case, with the assistance of recovery unit teams, State and Tribal agencies, and others. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views or the official positions or indicate the approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed by the Director or Regional Director as approved. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery tasks. Literature Citation: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2002. Chapter 18, Southwest Idaho Recovery Unit, Idaho. 110 p. In: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Bull Trout (Salvelinus confluentus) Draft Recovery Plan. Portland, Oregon. ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This chapter was developed with the assistance of the Southwest Idaho Bull Trout Recovery Unit Team, which includes: Dale Allen, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Dave Burns, U.S. Forest Service Tim Burton, U.S. Bureau of Land Management (formerly U.S. Forest Service) Chip Corsi, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Bob Danehy, Boise Corporation Jeff Dillon, Idaho Department of Fish and Game Guy Dodson, Shoshone-Paiute Tribes Jim Esch, U.S. -

Idaho Power Company's Fall Chinook Salmon Hatchery

IDAHO POWER COMPANY’S FALL CHINOOK SALMON HATCHERY PROGRAM Stuart Rosenberger, Paul Abbott, James Chandler 1221 W. Idaho St., Boise, Idaho Background The current Idaho Power Company (IPC) fall Chinook salmon program was established to provide mitigation for losses associated with the construction and operation of Brownlee, Oxbow, and Hells Canyon dams which together form the Hells Canyon Complex. IPC’s current mitigation goal is to produce 1 million fall Chinook salmon smolts annually (see Origination of Idaho Power Company’s Hatchery Mitigation Program section for more details). Oxbow Hatchery, funded by IPC and operated by the Idaho Department of Fish and Game, is responsible for the incubation and rearing of up to 200,000 subyearling fall Chinook salmon. The hatchery is located on the Snake River downstream of Oxbow Dam near the IPC village known as Oxbow, Oregon (Figure 1). IPC also contracts with the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (ODFW) for the production of an additional 800,000 subyearling fall Chinook salmon that were originally reared at ODFW’s Umatilla Hatchery and are now reared at ODFWs’ Irrigon Hatchery, both of which are located near the town of Irrigon, Oregon. Fish reared at both Oxbow and Umatilla/Irrigon hatcheries are released into the Snake River directly below Hells Canyon Dam with the exception of brood years 2003 to 2005 in which some of the production was released at the Nez Perce Tribe’s Pittsburg Landing acclimation facility. Similar to other fall Chinook salmon programs in the Snake Basin, Oxbow and Umatilla/Irrigon hatcheries receive eyed eggs from Lyons Ferry Hatchery, as it is one of only two broodstock holding and spawning facilities for fall Chinook salmon in the Snake Basin. -

West Crane Creek Ranchlands

WEST CRANE CREEK RANCHLANDS WEST CRANE CREEK RANCHLANDS 677± acres Ranchland & 246 aums on BLM Grazing Allotment Great Cow & Horse Prospect on South Crane Creek Road, Midvale, Idaho EXECUTIVE SUMMARY West Crane Creek Ranchlands are 677± deeded acres of beautiful mountain valley ranchlands with good grasses, springs, seasonal Milk Creek running through and a share in over 10,000 acres of a BLM grazing allotment, which can support close to 100 pair for 4.3 months in a normal year. Running along South Crane Creek Road, the ranchlands offer excellent year- round access. WCC Ranchlands offers spectacular vistas from the hilltops of its 677± deeded acres overlooking Crane Creek Reservoir and the ag-based valley. Nestled in a picturesque foothill basin it could be a great base for a horse & cow outfit. Northern Washington County is still cattle country with fertile croplands, lush pastures and mountain grass. EXCLUSIVELY REPRESENTED BY: Lon Lundberg, CLB, ABR, CCIM Land, Farm & Ranch Brokerage since 1995 www.gatewayra.com ofc: 208-939-0000 c:208-559-2120 [email protected] WEST CRANE CREEK RANCHLANDS Introducing: WEST CRANE CREEK RANCHLANDS WEST CRANE CREEK RANCHLANDS LOCATION Offering beautiful scenery and great access, the 677+ acre West Crane Creek Ranchlands is nestled in a valley basin accessed via Farm-to-Market Road to So. Crane Creek Road southeast of Midvale in Washington County, Idaho. The views from the hilltops offer vistas overlooking Crane Creek Reservoir and the grass-covered hills and valley with snow-capped peaks of Cuddy Mountain. Twenty+ minutes away is Highway 95, which affords excellent access to bring cattle to market, kids to lessons or games, recreational pursuits, fine dining or shopping in the Weiser River Valley, Treasure Valley or Ontario, OR and north to New Meadows, Riggins or McCall. -

Spring Chinook Salmon Dworshak National Fish Hatchery Clearwater River, Idaho

Spring Chinook Salmon Dworshak National Fish Hatchery Clearwater River, Idaho Howard Burge Ray Jones U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Idaho Fishery Resource Office Ahsahka, Idaho Idaho Washington NF Clearwater River Clearwater Lower Hatchery Columbia Lower Little Goose Granite Monumental Dam Dam Dam Dworshak Dam Clearwater R Dworshak Lochsa R River Snake NFH River Lewiston Kooskia IDFG Ice Harbor NFH Satellites Dam Selway River Rapid R Hatchery Hells Canyon Dam Oxbow Dam SF Clearwater McNary Brownlee Dam Dam Oregon Salmon River Program Goals 9,135 adults above Lower Granite Dam Harvest of 36,500 in ocean, Columbia River, and Lower Snake River fisheries Original production goal of 1.4 mil smolts Current production goal of 1.05 mil smolts - changed in 1996 Management Objectives Provide sport & tribal fishing opportunities in the Lower Clearwater River Return adequate broodstock to meet production needs Minimize impacts to natural populations Assist other programs in the Clearwater basin M & E Objectives Evaluate the effectiveness of the program so that it can be managed adaptively Determine the total adult return to assess if the program is meeting its mitigation goals Document and communicate programs success at meeting its program and management goals Coordinate hatchery and R,M & E activities Lewiston Dam 1929-1972 Leavenworth NFH 1983 - 86 Little White NFH 1983 & 85 1989 - 2010 Dworshak NFH Kooskia NFH 1995 Rapid River SH 1987 & 88 Broodstock sources and years Dworshak Spring Chinook Broodstock 50:50 ratio of males to females Approximately 65% of returning adults are 2-ocean Average size of a 2-ocean adult is 29 inches Average pre-spawn mortality (1995-2010) 3.1% Chinook arrive ~ May - August Spawning ~ late Aug - early Sept Juvenile Performance Rearing ~ approx. -

Hells Canyon Complex Total Dissolved Gas Study

Hells Canyon Complex Total Dissolved Gas Study Ralph Myers Project Limnologist Sharon E. Parkinson Principal Engineer Technical Report Appendix E.2.2-4 March 2002 Revised July 2003 Hells Canyon Complex FERC No. 1971 Copyright © 2003 by Idaho Power Company Idaho Power Company Hells Canyon Complex Total Dissolved Gas Study TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables...................................................................................................................................ii List of Figures .................................................................................................................................ii List of Appendices .........................................................................................................................iii Abstract ........................................................................................................................................... 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 2 2. Study Area.................................................................................................................................. 3 3. Plant Operations ......................................................................................................................... 4 4. Methods..................................................................................................................................... -

(E.3.2-42) Shoreline Erosion in Hells Canyon

Shoreline Erosion in Hells Canyon Gary L. Holmstead Terrestrial Ecologist Technical Report Appendix E.3.2-42 October 2001 Revised July 2003 Hells Canyon Complex FERC No. 1971 Copyright © 2003 by Idaho Power Company Idaho Power Company Shoreline Erosion In Hells Canyon TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................................. i List of Tables.................................................................................................................................. iv List of Figures ................................................................................................................................. v List of Appendices .......................................................................................................................... v Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................ 1 1. Introduction ................................................................................................................................ 4 2. Study Area.................................................................................................................................. 5 2.1. Location............................................................................................................................. 5 2.2. Political Boundaries ......................................................................................................... -

Your Guide to Exploring Southwest Idaho

EXPEDITION Your Guide to Exploring Southwest Idaho Weiser Midvale Cambridge Council New Meadows Open Burgers Salads Breakfast Dessert Fries 6 a.m.-11 p.m. 7 Days a Week Welcome We Are Open For Your Convenience 406 E. Main St. • Weiser, ID • 549-1636 Contents 6 10 14 WEISER MIDVALE CAMBRIDGE A community known for its The Midvale mercantile Known as the gate- world famous fiddle festival is the hub of this small way to Hells Canyon, is a destination with a lot Idaho town located Cambridge fills up with of things for visitors to see along U.S. Highway 95. visitors every June for and do. Check out the his- The friendly folks that Hells Canyon Days. tory as you shop and stroll live here invite you to It’s the one weekend of around downtown or visit stop for a spell. Take a the year when parking one of the best small-town dip in the city pool or spots are scarce. It’s museums around. picnic in the city park. also a great access point to jump on the Weiser River Trail. PUBLISHED BY 25 29 Features COUNCIL NEW WEISER SIGNALProudly serving the Weiser River Valley AMERICAN since 1882 Council is surrounded Fiddle Contest – 9 MEADOWS PUBLICATION TEAM by outdoor recreation New Meadows is Jack the Dog – 10 in all directions. After Publisher - Sarah Imada Hells Canyon – 16 & 21 located in one of the a day hiking, biking, most picturesque val- Editor - Steve Lyon Fishing – 16 fishing or hunt- Advertising - Tabitha Leija leys in Idaho. Breathe Hiking and Lookouts – 17 ing, stop by a local in that fresh mountain Brandie Lincoln Weiser River Trail – 20 restaurant in town to air. -

Clean Water Act Section 401 Water Quality Certification Hells Canyon Complex (FERC Project Number 1971)

Evaluation and Findings Report: Clean Water Act Section 401 Water Quality Certification Hells Canyon Complex (FERC Project Number 1971) May 2019 Northwest Region 700 NE Multnomah St. Suite 600 Portland, OR 97232 Phone: 503-229-5696 800-452-4011 Fax: 503-229-5850 www.oregon.gov/DEQ DEQ is a leader in restoring, maintaining and enhancing the quality of Oregon’s air, land and water. Oregon Department of Environmental Quality 401 Water Quality Certification Hells Canyon Complex (FERC Project Number 1971) This report prepared by: Oregon Department of Environmental Quality 700 NE Multnomah St Suite 600 Portland, OR 97232 1-800-452-4011 www.oregon.gov/deq Contact: Marilyn Fonseca 503-229-6804 Documents can be provided upon request in an alternate format for individuals with disabilities or in a language other than English for people with limited English skills. To request a document in another format or language, call DEQ in Portland at 503-229-5696, or toll-free in Oregon at 1-800-452-4011, ext. 5696; or email [email protected]. State of Oregon Department of Environmental Quality ii 401 Water Quality Certification Hells Canyon Complex (FERC Project Number 1971) Table of Contents 1 Introduction ......................................................................................................................................... 1 2 Requirements for Certification ............................................................................................................ 1 2.1 Applicable Federal and State Law .............................................................................................. -

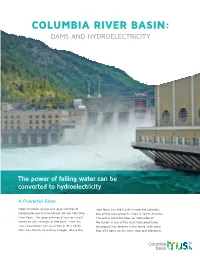

Dams and Hydroelectricity in the Columbia

COLUMBIA RIVER BASIN: DAMS AND HYDROELECTRICITY The power of falling water can be converted to hydroelectricity A Powerful River Major mountain ranges and large volumes of river flows into the Pacific—make the Columbia precipitation are the foundation for the Columbia one of the most powerful rivers in North America. River Basin. The large volumes of annual runoff, The entire Columbia River on both sides of combined with changes in elevation—from the the border is one of the most hydroelectrically river’s headwaters at Canal Flats in BC’s Rocky developed river systems in the world, with more Mountain Trench, to Astoria, Oregon, where the than 470 dams on the main stem and tributaries. Two Countries: One River Changing Water Levels Most dams on the Columbia River system were built between Deciding how to release and store water in the Canadian the 1940s and 1980s. They are part of a coordinated water Columbia River system is a complex process. Decision-makers management system guided by the 1964 Columbia River Treaty must balance obligations under the CRT (flood control and (CRT) between Canada and the United States. The CRT: power generation) with regional and provincial concerns such as ecosystems, recreation and cultural values. 1. coordinates flood control 2. optimizes hydroelectricity generation on both sides of the STORING AND RELEASING WATER border. The ability to store water in reservoirs behind dams means water can be released when it’s needed for fisheries, flood control, hydroelectricity, irrigation, recreation and transportation. Managing the River Releasing water to meet these needs influences water levels throughout the year and explains why water levels The Columbia River system includes creeks, glaciers, lakes, change frequently. -

Bull Trout Recovery Plan App Introduction

Chapter 13 - Hells Canyon INTRODUCTION Recovery Unit Designation The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit is 1 of 22 recovery units designated for bull trout in the Columbia River basin (Figure 1). The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit includes basins in Idaho and Oregon, draining into the Snake River and its associated reservoirs from below the confluence of the Weiser River downstream to Hells Canyon Dam. This recovery unit contains three Snake River reservoirs, Hells Canyon, Oxbow, and Brownlee. Major watersheds are the Pine Creek, Powder River, and Burnt River drainages in Oregon, and the Indian Creek and Wildhorse River drainages in Idaho. Inclusion of bull trout in the Oregon tributaries (i.e., Pine Creek and Powder River) in one recovery unit is based in part on a single gene conservation unit (i.e., roughly the major drainages in Oregon inhabited by bull trout) recognized by the Figure 1. Bull trout recovery units in the United States. The Hells Canyon Complex Recovery Unit is highlighted. 1 Chapter 13 - Hells Canyon Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife (Kostow 1995), which is supported by the genetic analysis conducted by Spruell and Allendorf (1997). Although the genetic composition of bull trout in the two tributaries in Idaho has not been extensively studied, the streams were included in the recovery unit due to their close proximity to the tributaries in Oregon containing bull trout, and the likelihood that bull trout from all tributaries were able to interact historically. Administratively, the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife established a working group to develop bull trout conservation strategies in Pine Creek, and the streams in Idaho were included in the Hells Canyon Key Watersheds in the Idaho Bull Trout Conservation Plan (Grunder 1999). -

The Hells Canyon Dam Controversy

N 1956, AT THE TENDER AGE OF THIRTY-TWO, Frank Church made a bold bid for the United States Senate. After squeak- I ing out a victory in the hotly contested Idaho Democratic pri- mary, Church faced down incumbent Senator Herman Welker, re- ceiving nearly percent of the vote. One issue that loomed over the campaign was an emerging dis- pute over building dams in the Snake River’s Hells Canyon. While Church and other Democrats supported the construction of a high federal dam in the Idaho gorge, their Republican opponents favored developing the resource through private utility companies. Idaho EVOLUTION voters split on the issue, and so, seeking to avoid a divisive debate, Church downplayed his position during the general election “be- of an cause it was not a winning issue, politically.”1 Senator Frank Church Although Church won the election, he could not escape the is- sue. Indeed, his victory and subsequent assignment to the Senate Committee on Interior and Insular Affairs put him at the center of a growing controversy about damming Hells Canyon. Over the next eighteen years, Church wrestled with balancing Idaho’s demand for economic growth and his own pro-development beliefs with an emerging environmental movement’s demand for preservation of nature—in Idaho and across the nation. As he grappled with these competing interests, Church under- went a significant transformation. While Church often supported development early in his Senate career, he, like few others of his time, began to see the value of wild places and to believe that rivers offered more than power production opportunities and irrigation water. -

Woodland Mountain Pastures Woodland

WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES 1282± acres of Mountain pastures for grazing livestock, plus big game & bird hunting Cambridge, ID EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Woodland Mountain Pastures offers wide open space, good spring grazing and fall hunting for mule deer, elk, occasional antelope, black bear, coyote, quail, partridge, and some upland bird. In addition, one may be able to spot a wolf, cougar, badger and other wild animals on or near the ranch property. There is good water for both domestic livestock and wildlife year-round with two of three ponds holding water yearlong. Owner reports that the grass will feed 200± head for 2.5 months (500± aums). Cattle/livestock are trailed through a neighbor’s land, which is common in this country, but a permanent access easement will need to be established, if a buyer so desired. There also may be the possibility of adding more ground as a couple neighbors have expressed interest in selling. “Put your money in land, because they aren't making any more of it.” Will Rogers, 1930 EXCLUSIVELY REPRESENTED BY: Lon Lundberg, CLB, ABR, CCIM Land, Farm & Ranch Brokerage since 1995 www.gatewayra.com Office 208-939-0000 cell 208-559-2120 [email protected] For info or to schedule a tour contact: Lon Lundberg 208.559.2120 WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES Introducing: WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES GATEWAY Realty Advisors Eagle, ID ©2017 contact Lon Lundberg, CLB, Ranch Broker www.gatewayra.com WOODLAND MOUNTAIN PASTURES LOCATION Known as the gateway to Hell’s Canyon from Idaho side of the Snake River, Cambridge is a picturesque small town with a strong sense of community that provides a variety of shops and services, a K-12 school system, churches, several popular café’s, lodging, groceries, lumber and hardware, banking, automotive repair and a medical clinic.