The Colfax Massacre

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Attorney General's Ninth Annual Report to Congress Pursuant to The

THE ATTORNEY GENERAL'S NINTH ANNUAL REPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVED CIVIL RIGHTS CRIME ACT OF 2007 AND THIRD ANNUALREPORT TO CONGRESS PURSUANT TO THE EMMETT TILL UNSOLVEDCIVIL RIGHTS CRIMES REAUTHORIZATION ACT OF 2016 March 1, 2021 INTRODUCTION This is the ninth annual Report (Report) submitted to Congress pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crime Act of2007 (Till Act or Act), 1 as well as the third Report submitted pursuant to the Emmett Till Unsolved Civil Rights Crimes Reauthorization Act of 2016 (Reauthorization Act). 2 This Report includes information about the Department of Justice's (Department) activities in the time period since the eighth Till Act Report, and second Reauthorization Report, which was dated June 2019. Section I of this Report summarizes the historical efforts of the Department to prosecute cases involving racial violence and describes the genesis of its Cold Case Int~~ative. It also provides an overview ofthe factual and legal challenges that federal prosecutors face in their "efforts to secure justice in unsolved Civil Rights-era homicides. Section II ofthe Report presents the progress made since the last Report. It includes a chart ofthe progress made on cases reported under the initial Till Act and under the Reauthorization Act. Section III of the Report provides a brief overview of the cases the Department has closed or referred for preliminary investigation since its last Report. Case closing memoranda written by Department attorneys are available on the Department's website: https://www.justice.gov/crt/civil-rights-division-emmett till-act-cold-ca e-clo ing-memoranda. -

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:_December 13, 2006_ I, James Michael Rhyne______________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: Doctor of Philosophy in: History It is entitled: Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _Wayne K. Durrill_____________ _Christopher Phillips_________ _Wendy Kline__________________ _Linda Przybyszewski__________ Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region A Dissertation submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Ph.D.) in the Department of History of the College of Arts and Sciences 2006 By James Michael Rhyne M.A., Western Carolina University, 1997 M-Div., Southeastern Baptist Theological Seminary, 1989 B.A., Wake Forest University, 1982 Committee Chair: Professor Wayne K. Durrill Abstract Rehearsal for Redemption: The Politics of Post-Emancipation Violence in Kentucky’s Bluegrass Region By James Michael Rhyne In the late antebellum period, changing economic and social realities fostered conflicts among Kentuckians as tension built over a number of issues, especially the future of slavery. Local clashes matured into widespread, violent confrontations during the Civil War, as an ugly guerrilla war raged through much of the state. Additionally, African Americans engaged in a wartime contest over the meaning of freedom. Nowhere were these interconnected conflicts more clearly evidenced than in the Bluegrass Region. Though Kentucky had never seceded, the Freedmen’s Bureau established a branch in the Commonwealth after the war. -

Glittering Generalilties and Historic Myths, Brandeis School of Law

For further information contact: EMBARGOED until 7:30 p.m. (E.D.T.) Public Information Office (202) 479-3211 April 18, 2013 JUSTICE JOHN PAUL STEVENS (Ret.) UNIVERSITY OF LOUISVILLE BRANDEIS SCHOOL OF LAW 2013 Brandeis Medal Recipient The Seelbach Hilton Louisville, Kentucky April 18, 2013 Glittering Generalities and Historic Myths When I began the study of constitutional law at Northwestern in the fall of 1945, my professor was Nathaniel Nathanson, a former law clerk for Justice Brandeis. Because he asked us so many questions and rarely provided us with answers, we referred to the class as "Nat's mystery hour." I do, however, vividly remember his advice to "beware of glittering generalities." That advice was consistent with his former boss's approach to the adjudication of constitutional issues that he summarized in his separate opinion in Ashwander v. TVA, 297 U. S. 288, 346 (1936). In that opinion Justice Brandeis described several rules that the court had devised to avoid the unnecessary decision of constitutional questions. As I explained in the first portion of my long dissent in the Citizens United case three years ago, the application of the Brandeis approach to constitutional adjudication would have avoided the dramatic changes in the law produced by that decision. I remain persuaded that the case was wrongly decided and that it has done more harm than good. Today, however, instead of repeating arguments in my lengthy dissent, I shall briefly comment on the glittering generality announced in the per curiam opinion in Buckley v. Valeo in 1976 that has become the centerpiece of the Court's campaign finance jurisprudence, and then suggest that in addition to being skeptical about glittering generalities, we must also beware of historical myths. -

Badges of Slavery : the Struggle Between Civil Rights and Federalism During Reconstruction

University of Louisville ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository Electronic Theses and Dissertations 5-2013 Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction. Vanessa Hahn Lierley 1981- University of Louisville Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.library.louisville.edu/etd Recommended Citation Lierley, Vanessa Hahn 1981-, "Badges of slavery : the struggle between civil rights and federalism during reconstruction." (2013). Electronic Theses and Dissertations. Paper 831. https://doi.org/10.18297/etd/831 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ThinkIR: The University of Louisville's Institutional Repository. This title appears here courtesy of the author, who has retained all other copyrights. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Liedey B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the College of Arts and Sciences of the University of Louisville in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts Department of History University of Louisville Louisville, KY May 2013 BADGES OF SLAVERY: THE STRUGGLE BETWEEN CIVIL RIGHTS AND FEDERALISM DURING RECONSTRUCTION By Vanessa Hahn Lierley B.A., University of Kentucky, 2004 A Thesis Approved on April 19, 2013 by the following Thesis Committee: Thomas C. Mackey, Thesis Director Benjamin Harrison Jasmine Farrier ii DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to my husband Pete Lierley who always showed me support throughout the pursuit of my Master's degree. -

HS Social Studies Distance Learning Activities

HS Social Studies (Oklahoma History/Government) Distance Learning Activities TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Dear families, These learning packets are filled with grade level activities to keep students engaged in learning at home. We are following the learning routines with language of instruction that students would be engaged in within the classroom setting. We have an amazing diverse language community with over 65 different languages represented across our students and families. If you need assistance in understanding the learning activities or instructions, we recommend using these phone and computer apps listed below. Google Translate • Free language translation app for Android and iPhone • Supports text translations in 103 languages and speech translation (or conversation translations) in 32 languages • Capable of doing camera translation in 38 languages and photo/image translations in 50 languages • Performs translations across apps Microsoft Translator • Free language translation app for iPhone and Android • Supports text translations in 64 languages and speech translation in 21 languages • Supports camera and image translation • Allows translation sharing between apps 3027 SOUTH NEW HAVEN AVENUE | TULSA, OKLAHOMA 74114 918.746.6800 | www.tulsaschools.org TULSA PUBLIC SCHOOLS Queridas familias: Estos paquetes de aprendizaje tienen actividades a nivel de grado para mantener a los estudiantes comprometidos con la educación en casa. Estamos siguiendo las rutinas de aprendizaje con las palabras que se utilizan en el salón de clases. Tenemos -

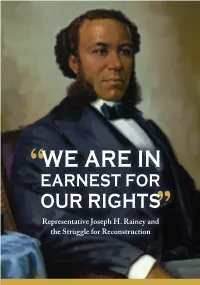

"We Are in Earnest for Our Rights": Representative

Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction On the cover: This portrait of Joseph Hayne Rainey, the f irst African American elected to the U.S. House of Representatives, was unveiled in 2005. It hangs in the Capitol. Joseph Hayne Rainey, Simmie Knox, 2004, Collection of the U.S. House of Representatives Representative Joseph H. Rainey and the Struggle for Reconstruction September 2020 2 | “We Are in Earnest for Our Rights” n April 29, 1874, Joseph Hayne Rainey captivity and abolitionists such as Frederick of South Carolina arrived at the U.S. Douglass had long envisioned a day when OCapitol for the start of another legislative day. African Americans would wield power in the Born into slavery, Rainey had become the f irst halls of government. In fact, in 1855, almost African-American Member of the U.S. House 20 years before Rainey presided over the of Representatives when he was sworn in on House, John Mercer Langston—a future U.S. December 12, 1870. In less than four years, he Representative from Virginia—became one of had established himself as a skilled orator and the f irst Black of f iceholders in the United States respected colleague in Congress. upon his election as clerk of Brownhelm, Ohio. Rainey was dressed in a f ine suit and a blue silk But the fact remains that as a Black man in South tie as he took his seat in the back of the chamber Carolina, Joseph Rainey’s trailblazing career in to prepare for the upcoming debate on a American politics was an impossibility before the government funding bill. -

African Americans Confront Lynching: Strategies of Resistance from The

African Americans Confront Lynching Strategies of Resistance from the Civil War to the Civil Rights Era Christopher Waldrep StrategiesofResistance.indd 1 9/30/08 11:52:02 AM African Americans Confront Lynching The African American History Series Series Editors: Jacqueline M. Moore, Austin College Nina Mjagkij, Ball State University Traditionally, history books tend to fall into two categories: books academics write for each other, and books written for popular audiences. Historians often claim that many of the popu- lar authors do not have the proper training to interpret and evaluate the historical evidence. Yet, popular audiences complain that most historical monographs are inaccessible because they are too narrow in scope or lack an engaging style. This series, which will take both chronolog- ical and thematic approaches to topics and individuals crucial to an understanding of the African American experience, is an attempt to address that problem. The books in this series, written in lively prose by established scholars, are aimed primarily at nonspecialists. They fo- cus on topics in African American history that have broad significance and place them in their historical context. While presenting sophisticated interpretations based on primary sources and the latest scholarship, the authors tell their stories in a succinct manner, avoiding jargon and obscure language. They include selected documents that allow readers to judge the evidence for themselves and to evaluate the authors’ conclusions. Bridging the gap between popular and academic history, these books bring the African American story to life. Volumes Published Booker T. Washington, W.E.B. Du Bois, and the Struggle for Racial Uplift Jacqueline M. -

INFORMATION to USERS This Manuscript Has Been Reproduced

INFO RM A TIO N TO U SER S This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI film s the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be fromany type of con^uter printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependentquality upon o fthe the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and inqjroper alignment can adverse^ afreet reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note wiD indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. Each original is also photographed in one e3q)osure and is included in reduced form at the back of the book. Photogr^hs included inoriginal the manuscript have been reproduced xerographically in this copy. Higher quality 6" x 9" black and white photographic prints are available for aiy photographs or illustrations appearing in this copy for an additional charge. Contact UMI direct^ to order. UMJ A Bell & Howell Information Company 300 North Zeeb Road. Ann Arbor. Ml 48106-1346 USA 313.'761-4700 800/521-0600 LAWLESSNESS AND THE NEW DEAL; CONGRESS AND ANTILYNCHING LEGISLATION, 1934-1938 DISSERTATION presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University By Robin Bernice Balthrope, A.B., J.D., M.A. -

Before Rosa Parks: Ida B. Wells Goals (Language Arts and U.S

TEACHING TOLERANCE MIDDLE GRADES ACTIVITY WWW.TEACHINGTOLERANCE.ORG K 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Before Rosa Parks: Ida B. Wells GOALS (LANGUAGE ARTS AND U.S. HISTORY TOPICS) • Students will consider the strategies Ida B. Wells deployed to raise awareness of social problems • Students will weigh the effectiveness of nonconformity to address a specific audience • Students will use Wells' story to write about a personal experience of conformity or non-conformity • Students will understand some of the economic and social problems facing the South after the Civil War RATIONALE Many people consider the 1950s the beginning of the Civil Rights Movement, creating a void between the abolition of slavery and Brown v. Board of Education. After the Emancipation Proclamation, however, abolitionists continued their activities to pass the 14th and 15th amendments to the constitution. During Reconstruction and well into the 20th century, black and white activists worked together to gain equality for blacks and women. TheH BO filmIron Jawed Angels features two short scenes that introduce a black feminist to the picture. This woman, who demanded the right to march with white suffragists and refused to go to the back of the parade to march separately, was Ida B. Wells. Coincidentally, Ida B. Wells spent much of her life in the South and struggled with segregation on public transportation, which makes a brief glance at her life and work an interesting precursor to thinking about Rosa Parks’ experience with Alabama public transportation almost 100 years later. You can read more about Wells from her diary, from which her daughter’s reflections are excerpted below.R ead The Memphis Diary of Ida B. -

Thomas Dixon, Jr

Negroes of New York By Michael Rothman / , Rev. Thomas Dixon, Jr. yRace Hatred Inc. At the turn of the century with the spectacle of Negroes beginning to find at long last their place in America's industrial and political scene as individualists, there arose from the dregs of intellectual morass the first of the articulate purveyors of race hatred* It was quite typical that this salesman would be a recognized member of the a South's reactionary landlord class,/descendant of Confederate officers, and a relative of the Ku Klux Klan's leadership. As if this were insufficient background, the "gentleman? had secured his reputation as a clergyman in the wealthiest of the Baptist churches. Truly an . ^ 7 excellant spokesman for his vicious masters. Thomas Dixon, Jr., was born in Cleveland County, North Carolina, on January 11, 1864. His father, the Baptist minister for the community, performed his paternal duties sufficiently well to eventually have hia son pass through the portals of Wake Forest College in North Carolina at the age of nineteen. The student Thomas was then sent to Johns Hopkins to study history and politics. As bright young man with good family connections, he was entered in the political arena and emerged as a member of North Carolina's legislature at the age of twenty even before his suffrage qualifications could be exercised^ Voting a straight pro-South policy according to the leaders must h6ve left him plenty of time forzhis page two efforts, for he began law studies at Greensboro Law School and was admitted to the bar InlLNjeMnH in 1886. -

Totalitarian Dynamics, Colonial History, and Modernity: the US South After the Civil War

ADVERTIMENT. Lʼaccés als continguts dʼaquesta tesi doctoral i la seva utilització ha de respectar els drets de la persona autora. Pot ser utilitzada per a consulta o estudi personal, així com en activitats o materials dʼinvestigació i docència en els termes establerts a lʼart. 32 del Text Refós de la Llei de Propietat Intel·lectual (RDL 1/1996). Per altres utilitzacions es requereix lʼautorització prèvia i expressa de la persona autora. En qualsevol cas, en la utilització dels seus continguts caldrà indicar de forma clara el nom i cognoms de la persona autora i el títol de la tesi doctoral. No sʼautoritza la seva reproducció o altres formes dʼexplotació efectuades amb finalitats de lucre ni la seva comunicació pública des dʼun lloc aliè al servei TDX. Tampoc sʼautoritza la presentació del seu contingut en una finestra o marc aliè a TDX (framing). Aquesta reserva de drets afecta tant als continguts de la tesi com als seus resums i índexs. ADVERTENCIA. El acceso a los contenidos de esta tesis doctoral y su utilización debe respetar los derechos de la persona autora. Puede ser utilizada para consulta o estudio personal, así como en actividades o materiales de investigación y docencia en los términos establecidos en el art. 32 del Texto Refundido de la Ley de Propiedad Intelectual (RDL 1/1996). Para otros usos se requiere la autorización previa y expresa de la persona autora. En cualquier caso, en la utilización de sus contenidos se deberá indicar de forma clara el nombre y apellidos de la persona autora y el título de la tesis doctoral. -

Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham ASALH National President

February 1, 2020 Dear ASALH Members and Friends: At the opening of Black History Month in 2020, ASALH invites all of America to reflect upon the annual theme “African Americans and the Vote.” The theme calls for the commemoration of two anniversaries— the sesquicentennial of the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment, by which black men gained the right to vote after the Civil War, and the centennial of the ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment, by which women won the vote. Yet, as we celebrate those constitutional milestones, history teaches us to be mindful of their limits—to recognize both the strides and the setbacks for African American men and women. In highlighting this precious right, so fundamental to democracy, we should boast of Senator Hiram Revels of Mississippi, Congressman Robert Brown Elliott of South Carolina, Governor P.B.S. Pinchback of Louisiana, and all the other black elected officials who courageously stood up for the rights of their people during the Reconstruction era of the 1870s and, afterward, in the bitter decades to follow. We should remember, as well, those in freedom’s first generation who lost their lives simply for attempting to register to vote or to exercise their right at the ballot box, as was the case in the Colfax Massacre in Louisiana in 1873. The triumph of women’s suffrage was also accompanied by the duality of gains and losses, since the achievement and denial of voting rights proved equally true for black women. Thus we should certainly champion the work of black suffragists, such as Mary Church Terrell, Ida B.