The Art of the Ancients: Persian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Historical Contextual Analysis Study of Persian Silk Fabric: (Pre-Islamic Period- Buyid Dynasty)

Proceedings of SOCIOINT 2017- 4th International Conference on Education, Social Sciences and Humanities 10-12 July 2017- Dubai, UAE A HISTORICAL CONTEXTUAL ANALYSIS STUDY OF PERSIAN SILK FABRIC: (PRE-ISLAMIC PERIOD- BUYID DYNASTY) Nadia Poorabbas Tahvildari1, Farinaz Farbod2, Azadeh Mehrpouyan3* 1Alzahra University, Art Faculty, Tehran, Iran and Research Institute of Cultural Heritage & Tourism, Traditional Art Department, Tehran, IRAN, [email protected] 2Alzahra University, Art Faculty, Tehran, IRAN, [email protected] 3Department of English Literature, Central Tehran Branch, Islamic Azad University, Tehran, IRAN, email: [email protected] *Corresponding author Abstract This paper explores the possibility existence of Persian silk fabric (Diba). The study also identifies the locations of Diba weave and its production. Based on the detailed analysis of Dida etymology and discovery locations, this paper present careful classification silk fabrics. Present study investigates the characteristics of Diba and introduces its sub-divisions from Pre-Islamic period to late Buyid dynasty. The paper reports the features of silk fabric of Ancient Persian, silk classification of Sasanian Empire based on discovery location, and silk sub-divisions of Buyaid dynasty. The results confirm the existence of Diba and its various types through a historical contextual analysis. Keywords: Persian Silk, Diba, Silk classification, Historical, context, location, Sasanian Empire 1. INTRODUCTION Diba is one of the machine woven fabrics (Research Institute of Cultural Heritage, Handicrafts and Tourism, 2009) which have been referred continuously as one of the exquisite silk fabrics during the history. History of weaving in Iran dated back to millenniums AD. The process of formation, production and continuity of this art in history of Iran took advantages of several factors such as economic, social, cultural and ecological factors. -

Title Transformation of Natural Elements in Persian Art: the Flora

Title Transformation of Natural Elements in Persian Art: the Flora Author(s) Farrokh, Shayesteh 名桜大学紀要 = THE MEIO UNIVERSITY BULLETIN(13): Citation 63-80 Issue Date 2007 URL http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12001/8061 Rights 名桜大学 名桜入学紀要 13号 63-80(2007) TransfbmationofNaturalElementsin PersianArt:theFlora FarrokhShayesteh ABSTRACT ThlSpaperisthefirstofatwo-partstudyonthetransformationofdifferentelementsofnora andfaunainPersianart. Usingcomponentsofnatureasmotifsisnotu】1uSualamongdi丘erentcultures;however,in Persiancultureitiswidespreadanduniquelyrepresentational.UnlikeWesternartthatwaspre- sentationalupuntilmoderntime,Persiana rt,evenbebretheadventofIslam,hasbeenrepresen- tational.Accordingly,throughalteration,deformation,andsimplificationofcomponentsofnature , abstractdesignshavebeencreated. Duringthecourseofthispaper,floraindiverseartformsisdiscussedinordertodemonstrate thecreativebreadthofabstractdesigns.Examples丘.omancienttimestothepresentareexamlned tosupportthisconclusion. Keywords:Abstraction,presentatiorVrepresentation,Persian ar t,Dora ペルシャ美術における自然物表現に関する研究 : 植物表現について フアロック ・シャイヤステ 要旨 本論文はペルシャ美術における動植物表現に関する 2 部か ら成る研究の第 1 部である。 様々な文化において、自然物 をモチーフとして取 り入れることは決 して稀ではない。ペルシャ 文化においては、自然 をモチーフとする表現は多 く、それらは独特な表象性 をもっている。描 写的な表現 を追及 し続けて きた西洋美術 とは異 な り、ペルシャ美術 はイスラム前 も後 も常に表 象的であ り続けた。その結果、自然物を修正、変形、そ して単純化することを通 して、抽象化 されたデザ インを創 り出 した。様々な芸術表現 に見 られる植物 デザ インが、抽象的デザインの 創造へ と発展 してい く過程 を検証することで本研究は進められる。古代から現代 までの例を挙 げなが ら結論へ と導いてい く。 キーワー ド:抽象化、描写性/表象性、ペ ルシャ美術 、植物 -63- Farrokh Shayesteh Introduction Plants and flowers have been extremely -

A Study on Islamic Human Figure Representation in Light of a Dancing Scene

Hanaa M. Adly A Study on Islamic Human Figure Representation in Light of a Dancing Scene Islamic decoration does indeed know human figures. This is a controversial subject1, as many Muslims believe that there can be no figural art in an Islamic context, basing their beliefs on the Hadith. While figural forms are rare in Muslim religious buildings, in much of the medieval Islamic world, figural art was not only tolerated but also encouraged.2 1 Richard Ettinghausen, ‘Islamic Art',’ The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, (1973) xxxiii , 2‐52, Nabil F. Safwat, ‘Reviews of Terry Allen: Five Essays on Islamic Art,’ ix. 131, Sebastopol, CA, 1988, Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies (BSOAS), (London: University of London, 1990), liii . 134‐135 [no. 1]. 2 James Allan, ‘Metalwork Treasures from the Islamic Courts,’ National Council for Culture, Art and Heritage, 2004, 1. 1 The aim of this research is to develop a comprehensive framework for understanding figurative art. This research draws attention to the popularization of the human figures and their use in Islamic art as a means of documenting cultural histories within Muslim communities and societies. Drinking, dancing and making music, as well as pastimes like shooting fowl and chasing game, constitute themes in Islamic figurative representations.3 Out of a number of dancing scenes. in particular, I have selected two examples from the Seljuqs of Iran and Anatolia in the 12th‐13th. centuries.4 One scene occurs on a ceramic jar (Pl. 1) and the other on a metal candlestick (Pl. 2).5 Both examples offer an excellent account of the artistic tradition of the Iranian people, who since antiquity have played an important role in the evolution of the arts and crafts of the Near East.6 The founder of the Seljuq dynasty, Tughril, took the title of Sultan in Nishapur in 1037 when he occupied Khurasan and the whole of Persia. -

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab

Islamic and Indian Art Including Sikh Treasures and Arts of the Punjab New Bond Street, London | 23 October, 2018 Registration and Bidding Form (Attendee / Absentee / Online / Telephone Bidding) Please circle your bidding method above. Paddle number (for office use only) This sale will be conducted in accordance with 23 October 2018 Bonhams’ Conditions of Sale and bidding and buying Sale title: Sale date: at the Sale will be regulated by these Conditions. You should read the Conditions in conjunction with Sale no. Sale venue: New Bond Street the Sale Information relating to this Sale which sets out the charges payable by you on the purchases If you are not attending the sale in person, please provide details of the Lots on which you wish to bid at least 24 hours you make and other terms relating to bidding and prior to the sale. Bids will be rounded down to the nearest increment. Please refer to the Notice to Bidders in the catalogue buying at the Sale. You should ask any questions you for further information relating to Bonhams executing telephone, online or absentee bids on your behalf. Bonhams will have about the Conditions before signing this form. endeavour to execute these bids on your behalf but will not be liable for any errors or failing to execute bids. These Conditions also contain certain undertakings by bidders and buyers and limit Bonhams’ liability to General Bid Increments: bidders and buyers. £10 - 200 .....................by 10s £10,000 - 20,000 .........by 1,000s £200 - 500 ...................by 20 / 50 / 80s £20,000 -

Mostly Modern Miniatures: Classical Persian Painting in the Early Twentieth Century

classical persian painting in the early twentieth century 359 MARIANNA SHREVE SIMPSON MOSTLY MODERN MINIATURES: CLASSICAL PERSIAN PAINTING IN THE EARLY TWENTIETH CENTURY Throughout his various writings on Persian painting Bek Khur¸s¸nº or Tur¸basº Bek Khur¸s¸nº, seems to have published from the mid-1990s onwards, Oleg Grabar honed to a fi ne art the practice of creative reuse and has explored the place of the medium in traditional replication. Indeed, the quality of his production, Persian culture and expounded on its historiography, represented by paintings in several U.S. collections including the role played by private collections, muse- (including one on Professor Grabar’s very doorstep ums, and exhibitions in furthering public appreciation and another not far down the road), seems to war- and scholarly study of Persian miniatures.1 On the rant designating this seemingly little-known painter whole, his investigations have involved works created as a modern master of classical Persian painting. His in Iran and neighboring regions from the fourteenth oeuvre also prompts reconsideration of notions of through the seventeenth century, including some of authenticity and originality within this venerable art the most familiar and beloved examples within the form—issues that Oleg Grabar, even while largely canonical corpus of manuscript illustrations and min- eschewing the practice of connoisseurship himself, iature paintings, such as those in the celebrated 1396 recognizes as a “great and honorable tradition within Dºv¸n of Khwaju Kirmani, the 1488 Bust¸n of Sa{di, and the history of art.”5 the ca. 1525–27 Dºv¸n of Hafi z. -

The Persian Achaemenid Architecture Art Its Impact ... and Influence (558-330BC)

Journal of Xi'an University of Architecture & Technology Issn No : 1006-7930 The Persian Achaemenid Architecture Art its Impact ... and Influence (558-330BC) Assistant professor Dr. Iman Lafta Hussein a a Department of History, College of Education, Al Qadisiya University, Ministry of Higher Education and Research, Republic of Iraq Abstract The Achaemenid Persians founded an empire that lasted for two centuries (550-331 BC) within that empire that included the regions of the Near East, Asia Minor, part of the Greek world, and highly educated people and people such as Babylon, Assyria, Egypt, and Asia Minor. Bilad Al-Sham, centers of civilization with a long tradition in urbanism and civilization, benefited the Achaemenids in building their empire and the formation of their civilization and the upbringing of their culture. It also secured under the banner of late in the field of civilization, those ancient cultures and mixed and resulted in the Achaemenid civilization, which is a summarization of civilizations of the ancient East and reconcile them, and architecture and art were part of those civilizational mixing, It was influenced by ancient Iraqi and Egyptian architecture as well as Greek art. In addition, it also affected the architecture of the neighboring peoples, and its effects on the architecture of India and Greece, as well as southern Siberia, but the external influences on the architecture of Achaemenid. It does not erase the importance of the special element and the ability to create a special architecture of Achaemenid civilization that has the character and characteristics and distinguish it from its counterparts in the ancient East. -

Margaret Cool Root

Curriculum Vitae MARGARET COOL ROOT EducationU 1969 Bryn Mawr College B.A. Classical and Near Eastern Archaeology (Magna cum Laude & Department Honors 1971 Bryn Mawr College M.A. Etruscan Archaeology 1976 Bryn Mawr College Ph.D. Near Eastern and Classical Archaeology and Etruscan Archaeology Specialization: Art & Archaeology of the Achaemenid Persian Empire ProfessionalU Employment l977-78 Visiting Assistant Professor: Department of Art and Department of Classical Languages and Literatures, University of Chicago Research Associate: Oriental Institute, University of Chicago l978-92 Assistant-Associate Professor of Classical and Near Eastern Art and Archaeology: Department of the History of Art and the Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA) Assistant-Associate Curator of Collections: Kelsey Museum of Archaeology 1992-present Professor of Classical and Near Eastern Art and Archaeology: Department of the History of Art and the Interdepartmental Program in Classical Art and Archaeology (IPCAA) Curator of Collections: Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan 1992-93 Acting Director, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan 1994-99 Chair, Department of the History of Art, University of Michigan 2004-05 Acting Director, Kelsey Museum of Archaeology, University of Michigan RelevantU Work-Related Experience l969 Trench Supervisor: Bryn Mawr College Excavations at Poggio Civitate (Murlo), Tuscany l97l-72 Museum/Site Study: Europe and North Africa l973-74 Dissertation Research: Turkey, Iran, London, -

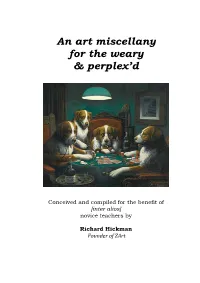

An Art Miscellany for the Weary & Perplex'd. Corsham

An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d Conceived and compiled for the benefit of [inter alios] novice teachers by Richard Hickman Founder of ZArt ii For Anastasia, Alexi.... and Max Cover: Poker Game Oil on canvas 61cm X 86cm Cassius Marcellus Coolidge (1894) Retrieved from Wikimedia Commons [http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/] Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue. Acrylic on board 60cm X 90cm Richard Hickman (1994) [From the collection of Susan Hickman Pinder] iii An art miscellany for the weary & perplex’d First published by NSEAD [www.nsead.org] ISBN: 978-0-904684-34-6 This edition published by Barking Publications, Midsummer Common, Cambridge. © Richard Hickman 2018 iv Contents Acknowledgements vi Preface vii Part I: Hickman's Art Miscellany Introductory notes on the nature of art 1 DAMP HEMs 3 Notes on some styles of western art 8 Glossary of art-related terms 22 Money issues 45 Miscellaneous art facts 48 Looking at art objects 53 Studio techniques, materials and media 55 Hints for the traveller 65 Colours, countries, cultures and contexts 67 Colours used by artists 75 Art movements and periods 91 Recent art movements 94 World cultures having distinctive art forms 96 List of metaphorical and descriptive words 106 Part II: Art, creativity, & education: a canine perspective Introductory remarks 114 The nature of art 112 Creativity (1) 117 Art and the arts 134 Education Issues pertaining to classification 140 Creativity (2) 144 Culture 149 Selected aphorisms from Max 'the visionary' dog 156 Part III: Concluding observations The tail end 157 Bibliography 159 Appendix I 164 v Illustrations Cover: Poker Game, Cassius Coolidge (1894) Frontispiece: (My Shirt is Alive With) Several Clambering Doggies of Inappropriate Hue, Richard Hickman (1994) ii The Haywain, John Constable (1821) 3 Vagveg, Tabitha Millett (2013) 5 Series 1, No. -

Book Arts of Isfahan: Diversity and Identity in Seventeenth-Century

BOOK ARTS OF ISFAHAN I S F A Diversity and Identity in Seventeenth-Century Persia Book Arts of H A N Alice Taylor TheJ. Paul Getty Museum Malibu, California © 1995 The J. Paul Getty Museum Library of Congress Cataloging-in- Title page illustrations (left to right): 17985 Pacific Coast Highway Publication Data Details ofShiru and Queen Mahzad in Her Malibu, California 90265-5799 Taylor, Alice, 1954- Gardens (pi. 9); An Armenian Bishop (pi. 5); Book arts of Isfahan: diversity and identity and Saint John Dictating His Gospel to Published on the occasion in seventeenth-century Prochoros (pi. 22). of an exhibition at Persia/Alice Taylor. The J. Paul Getty Museum p. cm. Front cover: October 24,1995-January 14,1996. Exhibition to be held Saint John Dictating His Gospel to Oct. 24,1995-Jan. 14, 1996 Prochoros. Mesrop of Khizan; Isfahan, 1615. Christopher Hudson, Publisher at the J. Paul Getty Museum. Fol. I93v of a Gospel book. JPGM, Ms. Mark Greenberg, Managing Editor ISBN 0-89236-362-2 (cloth) Ludwig II 7. John Harris, Editor ISBN 0-89236-338-x (paper) Leslie Thomas Fitch, Designer 1. Illumination of books and manuscripts, Back cover: Stacy Miyagawa, Production Coordinator Iranian—Iran—Isfahan—Exhibitions. Details of A Bearded Man Reading in a Charles Passela, Photography 2. Illumination of books and Landscape (pi. 2); Saint John Dictating Robert Hewsen, Map Designer manuscripts—Iran—Isfahan— His Gospel to Prochoros (pi. 22); and Shiru Exhibitions. 3. Illustration of books— and Queen Mahzad in Her Gardens (pi. 9). Typeset by G &. S Typesetters, Inc., 17th century—Iran—Isfahan— Austin, Texas Exhibitions. -

Central Asia-Geopolitical Impact on Art, Culture and Literature

JOURNAL OF ASIAN ARTS, CULTURE AND LITERATURE (JAACL) VOL 2, NO 2: JUNE 2021 Central Asia-Geopolitical impact on Art, Culture and Literature By Ms. Mousumee Baruah [email protected] Abstract The United Socialist Soviet Republic was once made up of fifteen strong republics Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Estonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Latvia, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. And the superpower unfortunately bogged down in the cold war, disintegrated, and ultimately experienced dissolution in 1991. The Collapse of the Soviet Union witnessed the birth and rise of few countries which were once part of erstwhile Soviet Russia. Though part of the Soviet republic, they have their distinctive culture and identity. And to preserve their heritage, they demanded a separate identity fuelled by the cold war. History has proven that every volatile region geographically or politically has its own distinctive cultural identity. So can Central Asia be far behind? Keywords Central Asia, Persian, art, culture, Silk Road Central Asia-Geopolitical impact on Art, Culture and Literature Central Asia is a region in Asia that extends from the Caspian Sea in the West to China and Mongolia in the east, Afghanistan, and Iran in the South to Russia in the north. The region consists of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. It is colloquially known as "the Stan's" as all the countries are from the same region and all have 1 JOURNAL OF ASIAN ARTS, CULTURE AND LITERATURE (JAACL) VOL 2, NO 2: JUNE 2021 names ending with the Persian suffix "Stan", meaning "land of" Various neighboring areas and also means part of the region. -

The Evolution of Persian Thought Regarding Art and Figural Repres

Macalester Islam Journal Volume 1 Spring 2006 Article 6 Issue 2 10-11-2006 The volutE ion of Persian Thought regarding Art and Figural Representation in Secular and Religious Life after the Coming of Islam Mashal Saif Macalester College Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/islam Recommended Citation Saif, Mashal (2006) "The vE olution of Persian Thought regarding Art and Figural Representation in Secular and Religious Life after the Coming of Islam ," Macalester Islam Journal: Vol. 1: Iss. 2, Article 6. Available at: http://digitalcommons.macalester.edu/islam/vol1/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Religious Studies Department at DigitalCommons@Macalester College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Macalester Islam Journal by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@Macalester College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Saif: The Evolution of Persian Thought regarding Art and Figural Repres Macalester Islam Journal Fall 2006 page 53 ______________________________________________________ The Evolution of Persian Thought regarding Art and Figural Representation in Secular and Religious Life after the Coming of Islam. Mashal Saif ’06, Ph.D. candidate, Duke University This paper argues that, although Islam never succeeded in completely wiping out the use of figural representation in Persian arts, it did manage to have a significant effect on Persian artistic forms and their appreciation. The Islamic prohibition on figural representation resulted in a shift from artistic emphasis being placed almost solely on figural representation (as was the case in pre-Islamic Persia) to a greater emphasis being placed on abstract, geometrical vegetal and floral art. -

Parliamentary' Patter HOW BIG IS BIG BILL!

HOW BIG IS BIG BILL! GRID4TEB BRISBANI] LAMB/iSTS U]«I¥C]BS1T¥ TEIVNIS CLVB The 1957 meeting of the Greater Brisbane Hard court Tennis Association saw a University club placed in the unique position of facing a meeting which was not merely patently hostile towards the University, hut hostile for no other reason than that it had been told to be hostile. HOW DH) THIS SITUATION ARISE? Mr. Edwards, In a Bcene University men Jones, The biggest name in Qu(>ensland tennis is that quite tuiprccedented lu a llalllgnn and K>1»i of Mr. C. A. ("Biff BiU") Edwards, a staunch up public meeting, aru!k> in wore lUrcady on. holder of Labor ideals, blessed with political con the chair, nnd i^tutcd that • Fallini!; to hrowlH'at tacts and £ s. d. — and a desire to havo his own two largo clubs hii<l acted University Into Htili- in collusion tn uuKcat the mlsslcn, ho threatens way. His taste in shirts mdicates a certain lack vjcp-prc»idents of the pre KeV Malyn hi sucjj THE NEWSPAPER OF THE UNIVERSITY OF QUEENSLAND of dress sense, but that is about all he does lack. vious year, and that they severe terms that STUDENTS' UNION The other protaganist is Mr. Clem Jones, presi- Maljii decides not to should not vote for Mr. nominate. Vol. XXVII. No. 3. Thursday, 14th March, 1057 went of the U.Q.T.C., and also a man of many Clem Jones, but they parts, political contacts, and £ s. d. As befits the WIIV? true University man, however, he is fashion con scious.