Technology Matters

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Citizen Culture Issue #4

issue 4.qxd 12/29/04 7:17 PM Page 1 Citizen Culture(Fourth Issue).ai 12/22/2004 12:25:09 PM THE Magazine for the Young Intellectual | www.CitizenCulture.com | Number Four A Trio of Interviews: A Trio of Interviews: AA Celebration Celebration of of DirectorDirector DavidDavid O.O. Russell Russell FictionFiction onon hishis filmfilm II HuckabeesHuckabees && andand “jumping“jumping offoff thethe cliff”cliff” Year-in-ReviewYear-in-Review C NATASSIAATASSIA MALTHEALTHE ofof EELEKTRALEKTRA M N M Y onon religion,religion, alchemyalchemy andand auditionsauditions CM MY TTHEHE CY SSPOOKYPOOKY SSIDEIDE CMY EERICRIC UUTNETNE,, FFOUNDEROUNDER OF OF UUTNETNE MMAGAZINEAGAZINE,, OFOF CCOMICSOMICS K publishedpublished aa bookbook byby aa birdbird TTHEHE CCMCCM IINVESTIGATESNVESTIGATES:: WWICKEDICKED RRABBITABBIT WWATCHESATCHES AreAre NewNew VotingVoting MethodsMethods ——DonnieDonnie DarkoDarko-style-style EvenEven LessLess Trustworthy?Trustworthy? IISS NNEWEW YYORKORK CCITYITY’’SS RREOPENEDEOPENED MMOOMMAA versusversus PoliticsPolitics Culture:Culture: WWORTHORTH VVISITINGISITING?? RealityReality onon thethe FenceFence PlusPlus PORTFOLIOS:PORTFOLIOS: $4.00 U.S. $5.00 CAN. Celebrities,Celebrities,andand 04 eveneven punctuationpunctuation (!),(!), CanCan BecomeBecome GorgeousGorgeous ArtArt 0274470 07418 issue 4.qxd 12/29/04 7:17 PM Page 2 issue 4.qxd 12/29/04 7:17 PM Page 3 the contents C i t i z e n C u l t u r e Number 4 6 12 38 features FABLE EYEWITNESS 6 The Cathedral 34 by Pamela Taylor The Night of the 1,000 by Matthew Bonavita NAIL BITER 12 MEMOIR The -

Metal Music Since the 1980S

Marrington, Mark ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5404-2546 (2017) From DJ to djent- step: Technology and the re-coding of metal music since the 1980s. Metal Music Studies, 3 (2). pp. 251-268. Downloaded from: http://ray.yorksj.ac.uk/id/eprint/2328/ The version presented here may differ from the published version or version of record. If you intend to cite from the work you are advised to consult the publisher's version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1386/mms.3.2.251_1 Research at York St John (RaY) is an institutional repository. It supports the principles of open access by making the research outputs of the University available in digital form. Copyright of the items stored in RaY reside with the authors and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full text items free of charge, and may download a copy for private study or non-commercial research. For further reuse terms, see licence terms governing individual outputs. Institutional Repository Policy Statement RaY Research at the University of York St John For more information please contact RaY at [email protected] Mark Marrington, From DJ to djent-step: Technology and the re-coding of metal music since the 1980s Mark Marrington trained in composition and musicology at the University of Leeds (M.Mus., Ph.D.) and is currently a Senior Lecturer in Music Production at York St John University. He has previously held teaching positions at Leeds College of Music and the University of Leeds (School of Electronic and Electrical Engineering). Mark has published chapters with Cambridge University Press, Bloomsbury Academic, Routledge and Future Technology Press and contributed articles to British Music, Soundboard, the Musical Times and the Journal on the Art of Record Production. -

CSU May Gain Autonomy to Administer Budget by LAURA KLEINMAN During a Meeting with the Board of Dents and Faculty Alike

THURSDAY 0:I-ARIAN Once again, etc. explores 'Al') AUX solitary leisure by beating V0L 100, No. 23 Pubhshed for San Jose State University since 1934 I linr,d.it, Ltrth 4, 199 I around the bush. CSU may gain autonomy to administer budget BY LAURA KLEINMAN during a meeting with the Board of dents and faculty alike. ber of units. such a way as to best meet the needs of Spartan Doily Stall Writer llustees earlier this year. "If you have a poor education, there's "We're going to have an enormous the community. As Gov. Wilson's proposed 1993-94 The governor has lifted a lot of what is not much point in having one," Evans increase in enrollment over the next five Students aren't the only people on budget continues to cut away at CSU commonly termed as "budget language said. to 10 years 50 percent more than we campus facing compromises. funding, administrators continue to look SJSU President J. Handel Evans said. Evans made the comment after rank- have now," Evans said. In his report to the Board of Trustees, for creative solutions to program access, "Budget language is language added to ing the importance of educational quali- "Those students will be representative Munitz said faculty also face a "trade-off quality and funding concerns. the budget by the legislature or by the ty and access above financial aid and the of the 'new California: as I like to put it," between job security, compensation, and "The general approach of the budget governor to tell us not only how much we price of education during a press confer- Evans said. -

Thesis Fulltext.Pdf (1.105Mb)

Commodified Evil’s Wayward Children: Black Metal and Death Metal as Purveyors of an Alternative Form of Modern Escapism A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Religious Studies in the University of Canterbury by Jason Forster University of Canterbury 2006 Contents Abstract 1 Introduction 2 1. Black Metal and Death Metal Music 5 Audible Distinctions and Definitions: both of and between Black Metal and Death Metal Music 5 Dominant Lyrical Themes and Foci 10 A Brief History of Black Metal and Death Metal Music 15 A Complementary Dichotomy of Evil 41 2. The Nature and Essence of Black Metal and Death Metal 46 The Eclectic Nature of Black Metal and Death Metal 46 The Hyperreal Nature of Black Metal and Death Metal 54 The Romantic Nature of Black Metal vs The Futurist Nature of Death Metal 59 The Superficial Nature of Black Metal and Death Metal 73 3. Black Metal and Death Metal as purveyors of an Alternative form of Modern Escapism 80 Escapism 80 Mainstream Escapism and the “Good Guys Always Win” Motif 83 Embracing an Evil Alternative 92 A Desensitizing Ethos of Utter Indifference 99 4. The (Potential) Social Effects of Black Metal and Death Metal 103 Lyrical Efficacy 103 (Potential) Negative Social Effects 108 (Potential) Positive Social Effects 126 Conclusion 130 Bibliography 133 Abstract This study focuses on Black Metal and Death Metal music as complimentary forms of commodified evil, which, in contrast to most other forms of commodified evil, provide an alternative form of modern escapism. -

The History of Rock Music - the Nineties

The History of Rock Music - The Nineties The History of Rock Music: 1989-1994 Raves, grunge, post-rock History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) From Grindcore to Stoner-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") A metal nation TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. If the 1980s had been the golden age of heavy metal, the age when heavy metal was accepted by the masses and climbed the charts, the 1990s saw the fragmentation of the genre into rather different styles, that simply expanded on ideas of the 1980s. As usual, pop-metal, the genre that appealed to the masses, was, artistically speaking, the least significant variant of heavy metal. It spawned stars such as Los Angeles' Warrant, with Cherry Pie (1990); Boston's Extreme, who specialized in "metal-operas" a` la Queen such as Pornograffiti (1990); and Pennsylvania's Live, with Throwing Copper (1994); etc. Los Angeles had to live with remnants of its "street-scene" (Guns N' Roses, Jane's Addiction), although they sounded a lot less sincere and a lot less powerful than the original masters: Ugly Kid Joe, Life Sex And Death, Dishwalla, Ednaswap, etc. Glam-metal staged a comeback of sorts in Florida with Marilyn Manson (1), the product of Brian Warner's deranged mind. -

Being Digital

BEING DIGITAL BEING DIGITAL Nicholas Negroponte Hodder & Stoughton Copyright © Nicholas Negroponte 1995 The right of Nicholas Negroponte to be identified as the Author of the Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published in Great Britain in 1995 by Hodder and Stoughton A division of Hodder Headline PLC Published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. A CIP catalogue record for this title is available from the British Library ISBN 0 340 64525 3 Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays of Chatham PLC, Chatham, Kent Hodder and Stoughton A division of Hodder Headline PLC 338 Euston Road London NW1 3BH To Elaine who has put up with my being digital for exactly 11111 years CONTENTS Introduction: The Paradox of a Book 3 Part One: Bits Are Bits 1: The DNA of Information 11 2: Debunking Bandwidth 21 3: Bitcasting 37 4: The Bit Police 51 5: Commingled Bits 62 6: The Bit Business 75 Part Two: Interface 7: Where People and Bits Meet 89 8: Graphical Persona 103 9: 20/20 VR 116 VII 10: Looking and Feeling 127 11: Can We Talk About This? 137 12: Less Is More 149 Part Three: Digital Life 13: The Post Information Age 163 14: Prime Time Is My Time 172 15: Good Connections 184 16: Hard Fun 196 17: Digital Fables and Foibles 206 18: The New E-xpressionists 219 Epilogue: An Age of Optimism 227 Acknowledgments 233 Index 237 VIII being digital INTRODUCTION: THE PARADOX OF A BOOK eing dyslexic, 1 don11 like to read. -

The Second Self: Computers and the Human Spirit

M820046FRONT.qxd 11/1/05 8:06 AM Page 1 computers/psychology/human development ,!7IA2G2-habbbc!:t;K;k;K;k T he Second Self The Second Self The Second Self Computers and the Human Spirit Twentieth Anniversary Edition Computers and the Human Spirit Sherry Turkle In The Second Self, Sherry Turkle looks at the computer not as a “tool,” but as part of our social and psychological lives; she looks beyond how we use computer games and spreadsheets to explore how the computer affects our awareness of ourselves, of one another, and of our relationship 0-262-70111-1 with the world. “Technology,” she writes, “catalyzes changes not only in what we do but in how we think.” First published in 1984, The Second Self is still essential reading as a primer in the psychology of computation. This twentieth anniversary edition allows us to reconsider two decades of computer culture—to (re)experience what was and is most novel in our new media culture and to view our own contemporary relationship with technology with fresh eyes. Turkle frames this classic work with a new introduction, a new epilogue, and extensive notes added to the original text. Sherry Turkle Turkle talks to children, college students, engineers, AI scientists, hackers, and personal com- puter owners—people confronting machines that seem to think and at the same time suggest a new way for us to think—about human thought, emotion, memory, and understanding. Her inter- “A brilliant and challenging views reveal that we experience computers as being on the border between inanimate and animate, Turkle as both an extension of the self and part of the external world. -

Thesis-1998D-P916a.Pdf (2.019Mb)

ASKING IN THE VOID OF THE ANSWER: THE PEDAGOGY OF INQUIRY AND THE DISCOURSE OF DISCOVERY By MICHAEL PRATT Bachelor of Science California State University Northridge, California 1967 Master of Arts California State University Northridge, California 1968 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May, 1998 .,('/nt~L> - t°l"ll(p \? q ~" 0\ ASKING IN THE VOID OF THE ANSWER: THE PEDAGOGY OF INQUIRY AND THE DISCOURSE OF DISCOVERY Thesis Approved: ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 PART I SUBJECT MATTERS Chapter 1 Blood Knowledge and Ancient Authority 13 Chapter 2 A Thrall Twists in the Traces 25 Chapter 3 Free at Last 42 Chapter 4 The Essay as Examination 56 Chapter 5 Revolution and Renaissance 69 PART II FORMAL PROBLEMS Chapter 6 Performance Privileged by Reward 80 Chapter 7 Temptation Sin Redemption 95 Chapter 8 An Idea of a Different Order 120 PART III INTERVENTIONS Chapter 9 Correct Me If I Am Wrong 158 Chapter 10 Two Heads Are Better than One and Too Many Cooks Spoil the Broth 179 Chapter 11 The Myth of Aztlan: Reflections on a Professional Dilemma 199 iii Endnotes 219 Works Cited 231 iv Asking in the Void of The Answer: The Pedagogy of Inquiry and the Discourse of Discovery Introduction The boy and his mother are a modest scandal in the apartment building. She purports to be an artist. The pictures of her three year old boy are a mess. "See, if you would teach him to wash his brush between using his colors," instructs her neighbor Jan, "then he would have pretty, clean, reds and blues." The mother nods in agreement; the grey-browns of her son's palette are disagreeable. -

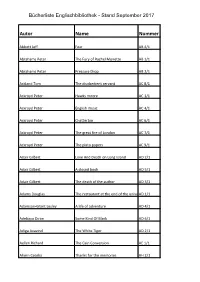

Autor Name Nummer

Bücherliste Englischbibliothek - Stand September 2017 Autor Name Nummer Abbott Jeff Fear AB 4/1 Abrahams Peter The Fury of Rachel Monette AB 1/1 Abrahams Peter Pressure Drop AB 2/1 Ackland Tom The disobedient servant AC 8/1 Ackroyd Peter Hawks moore AC 1/1 Ackroyd Peter English music AC 4/1 Ackroyd Peter Chatterton AC 6/1 Ackroyd Peter The great fire of London AC 7/1 Ackroyd Peter The plato papers AC 9/1 Adair Gilbert Love And Death on Long Island AD 2/1 Adair Gilbert A closed book AD 5/1 Adair Gilbert The death of the author AD 3/1 Adams Douglas The restaurant at the end of the universeAD 1/1 Adamson-Grant Lesley A life of adventure AD 4/1 Adebayo Diran Some Kind Of Black AD 6/1 Adiga Avavind The White Tiger AD 2/1 Aellen Richard The Cain Conversion AE 1/1 Ahern Cecelia Thanks for the memories AH 2/1 Aird Catherine Henrietta Who? AI 1/1 Alan Sillitoe Saturday Night and Sunday Morning SL 3/7 Albeury Ted The twentieth day of january AL 10/1 Albeury Ted Moscow quadrille Al 19/1 Albeury Ted The Lantern network AL 6/2 Albeury Ted The Lantern network AL 6/3 Albeury Ted The reaper Al 8/1 Albom Mitch tuesdays with Morrie AL 27/1 Albom Mitch For ond more day AL 29/1 Albom Mitch for one more day AL 29/2 Albom Mitch The five people you meet in heaven Al 30/1 Alcott Louisa M. -

Metal Music As Critical Dystopia: Humans, Technology and the Future in 1990S Science Fiction Metal

Metal Music as Critical Dystopia: Humans, Technology and the Future in 1990s Science Fiction Metal Laura Taylor Department of Communications, Popular Culture and Film Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Interdisciplinary MA in Popular Culture Faculty of Social Sciences and Faculty of Humanities, Brock University St. Catharines, Ontario © October, 2006 Abstract Metal Music as Critical Dystopia: Humans, Technology and the Future in 1990s Science Fiction Metal seeks to demonstrate that the dystopian elements in metal music are not merely or necessarily a sonic celebration of disaster. Rather, metal music's fascination with dystopian imagery is often critical in intent, borrowing themes and imagery from other literary and cinematic traditions in an effort to express a form of social commentary. The artists and musical works examined in this thesis maintain strong ties with the science fiction genre, in particular, and tum to science fiction conventions in order to examine the long-term implications of humanity's complex relationship with advanced technology. Situating metal's engagements with science fiction in relation to a broader practice of blending science fiction and popular music and to the technophobic tradition in writing and film, this thesis analyzes the works of two science fiction metal bands, VOlvod and Fear Factory, and provides close readings of four futuristic albums from the mid to late 1990s that address humanity's relationship with advanced technology in musical and visual imagery as well as lyrics. These recorded texts, described here as cyber metal for their preoccupation with technology in subject matter and in sound, represent prime examples of the critical dystopia in metal music. -

Antigravity-September-2017

FOUNDER Leo J. McGovern III PUBLISHER & EDITOR IN CHIEF Dan Fox [email protected] SENIOR EDITOR Erin Hall [email protected] PHOTO EDITOR barryfest.comAdrienne Battistella [email protected] COMICS EDITOR Caesar Meadows [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITORS Norah Emily [email protected] Andru Okun [email protected] Robert Landry [email protected] Elizabeth Vash Williams [email protected] ADVERTISING [email protected] WRITERS William Archambeault Jenn Attaway Travis Bird Corey Cruse Yvette Del Rio Susan Fox Christina Igoe Joey Laura Morgan Lawrence Dan McCoy Ben Miotke Edward Pellegrini Brooke Sauvage Alex Taylor Ian Willson PHOTOGRAPHERS Parish Achenbach Zach Brien Beau Patrick Coulon Jared Landry Zack Smith ILLUSTRATORS Victoria Allen Happy Burbeck Ben Claassen III Melissa Guion "CAN WE START THE WORK OF Kallie Max Ward L. Steve Williams HONESTLY SAYING, I'M SORRY?"PG. 17 SNAIL MAIL P.O. Box 2215 Gretna, LA 70054 LETTER TO THE EDITOR: I won’t lie: I get kind of testy around more importantly, the news from a lot to celebrate, from the spirit and [email protected] deadline. To everyone who suffers in Houston and southeast Texas has been fire of the Downtown Boys, to the deep my wake during this time, all apologies. heartbreaking and uncomfortably psychic dives of Mondo Bizarro, or the cover illustration by It’s always a challenge the last week familiar, as it reverberates against bucolic thrills of birding. And of course Happy Burbeck of a good month, and this past August another Katrinaversary and the there are quite a few other diversions to was not a good month. -

Index 1349 (Band), 156 “2112,” 102 324 (Band), 149 Abaddon (Venom

Index Anderson, Billy, 111, 114-15 “Angel of Death” (Angel Witch song), 154 1349 (band), 156 Angel Witch, 15, 154 “2112,” 102 Anger, Ed, 32 324 (band), 149 Anthrax, 15-17, 20-22, 26-28, 34-38, 40-45, 54, 57, 63, 69-70, 73, 78, 83, Abaddon (Venom member), 56 108, 110, 121, 123-24, 126, 128, 132, 134, 151, 155 ABC No Rio (venue), 100 Behind the Music special of, 132 Abrams, Howie, 37, 41, 58, 62-63, 70, 96 Formation of, 15-17 Abril, Maria, 77 “Antihomophobe,” 71 Abscess, 128-29, 153 Apocalypse Now (film), 95 AC/DC, 14 Araya, Tom, 22, 72-73 Acid Bath, 105 Arch Enemy, 74 Acid Reign, 64 “Aren’t You Hungry?” 35 Acoustic Amplifiers, 34 “Armed and Dangerous,” 34 The Adolescents, 55 Arnold, Paul, 74 Adrenaline OD, 41 “As Blood Flows,” 114 Aerosmith, 27 Asma, Tom, 96 Agathocles, 77 Assault & Battery, 134 Agent Steel, 43, 56-57 Assault Attack, 40 Agnew, Rikk, 55 Assembled in Blasphemy. 129, 139 Agnostic Front, 26, 31-34, 41, 62-63, 126-27 Assück, 78 Live at CBGB, 63 At the Gates, 148 Ain, Martin, 55 At War, 74 Aiosa, Rob, 62, 96 Atomkraft, 43, 56 “Alas, Alack, It’s Time to Pack” (poem), 13 “Attack Dog,” 151 Alcatraz (bar), 123 Attack of the Killer A’s, 127 All in the Family (TV show), 14 Attica Studio, 6 Altars of Madness, 6, 115 Auditory Assault Fest, 149 Alver, Jonas, 121 Autopsy, 62, 128, 153-54 Amityville Horror (film), 116 Azalin (Hemlock member), 122, 125 Amon Amarth, 115 Baby Monster Studios, 80, 102 Among the Living, 35-36 Bad Brains, 27, 63, 146 Amorphis, 80 Baker, Cary, 58 Anal Cunt, 26 Bakker, Jim, 67 Anathama, 86 Baloff, Paul, 138 Ballou,