The Self-Actualization of John Adams

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Doctor Atomic

What to Expect from doctor atomic Opera has alwayS dealt with larger-than-life Emotions and scenarios. But in recent decades, composers have used the power of THE WORK DOCTOR ATOMIC opera to investigate society and ethical responsibility on a grander scale. Music by John Adams With one of the first American operas of the 21st century, composer John Adams took up just such an investigation. His Doctor Atomic explores a Libretto by Peter Sellars, adapted from original sources momentous episode in modern history: the invention and detonation of First performed on October 1, 2005, the first atomic bomb. The opera centers on Dr. J. Robert Oppenheimer, in San Francisco the brilliant physicist who oversaw the Manhattan Project, the govern- ment project to develop atomic weaponry. Scientists and soldiers were New PRODUCTION secretly stationed in Los Alamos, New Mexico, for the duration of World Alan Gilbert, Conductor War II; Doctor Atomic focuses on the days and hours leading up to the first Penny Woolcock, Production test of the bomb on July 16, 1945. In his memoir Hallelujah Junction, the American composer writes, “The Julian Crouch, Set Designer manipulation of the atom, the unleashing of that formerly inaccessible Catherine Zuber, Costume Designer source of densely concentrated energy, was the great mythological tale Brian MacDevitt, Lighting Designer of our time.” As with all mythological tales, this one has a complex and Andrew Dawson, Choreographer fascinating hero at its center. Not just a scientist, Oppenheimer was a Leo Warner and Mark Grimmer for Fifty supremely cultured man of literature, music, and art. He was conflicted Nine Productions, Video Designers about his creation and exquisitely aware of the potential for devastation Mark Grey, Sound Designer he had a hand in designing. -

Alternately Known As 1313; Originally Releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, Numerous Intervening Reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform

UNIVERS ZERO UNIVERS ZERO CUNEIFORM 2008 REISSUE W BONUS TRACKS & REMASTER (alternately known as 1313; originally releases 1977 by UZ, 1977 by Atem, numerous intervening reissues, 1990 by Cuneiform) Cuneiform 2008 album features: Michel Berckmans [bassoon], Daniel Denis [percussion], Marcel Dufrane [violin], Christian Genet [bass], Patrick Hanappier [violin, viola, pocket cello], Emmanuel Nicaise [harmonium, spinet], Roger Trigaux [guitar], and Guy Segers [bass, vocal, noise effects] “ALBUM OF THE WEEK...Released in 1977, it was astonishing then: today, it sounds like the hidden source for every one of today's avant-garde rock bands. Chillingly beautiful, driven by the bassoon and cello more than the guitar and synth, each instrumental is both pastoral and burgeoning with terrible life. … This is edgy beyond belief. …Each piece magnificently refuses to deviate from its mood, its tense, thrilling, growling, restrained focus... The whole is like the rare, delicious bits of great film soundtrack that create menace and energy out of nowhere. … Univers Zero are a revelation …” – Sean O., Organ, #274, September 18th, 2008 “UZ's debut remains both benchmark and landmark. Reissued numerous times over the years…this definitive version finally presents this unprecedented music the way it was meant to be heard, clarifying how—emerging out of nowhere with little history to precede it— UZ has been so vital in changing the way chamber music is perceived. UZ's music was an antecedent for the kind of instrumental and stylistic interspersion considered normal today by groups including Bang on a Can and Alarm Will Sound. Henry Cow's complex, abstruse writing meets Bartok, Stravinsky, Messiaen and Ligeti, but with hints of early music, especially in UZ's use of spinet and harmonium. -

Cds by Composer/Performer

CPCC MUSIC LIBRARY COMPACT DISCS Updated May 2007 Abercrombie, John (Furs on Ice and 9 other selections) guitar, bass, & synthesizer 1033 Academy for Ancient Music Berlin Works of Telemann, Blavet Geminiani 1226 Adams, John Short Ride, Chairman Dances, Harmonium (Andriessen) 876, 876A Adventures of Baron Munchausen (music composed and conducted by Michael Kamen) 1244 Adderley, Cannonball Somethin’ Else (Autumn Leaves; Love For Sale; Somethin’ Else; One for Daddy-O; Dancing in the Dark; Alison’s Uncle 1538 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Favorite Standards (vol 22) 1279 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Gettin’ It Together (vol 21) 1272 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: Jazz Improvisation (vol 1) 1270 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: Major and Minor (vol 24) 1281 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 1 Aebersold, Jamey: One Dozen Standards (vol 23) 1280 pt. 2 Aebersold, Jamey: The II-V7-1 Progression (vol 3) 1271 Aerosmith Get a Grip 1402 Airs d’Operettes Misc. arias (Barbara Hendricks; Philharmonia Orch./Foster) 928 Airwaves: Heritage of America Band, U.S. Air Force/Captain Larry H. Lang, cond. 1698 Albeniz, Echoes of Spain: Suite Espanola, Op.47 and misc. pieces (John Williams, guitar) 962 Albinoni, Tomaso (also Pachelbel, Vivaldi, Bach, Purcell) 1212 Albinoni, Tomaso Adagio in G Minor (also Pachelbel: Canon; Zipoli: Elevazione for Cello, Oboe; Gluck: Dance of the Furies, Dance of the Blessed Spirits, Interlude; Boyce: Symphony No. 4 in F Major; Purcell: The Indian Queen- Trumpet Overture)(Consort of London; R,Clark) 1569 Albinoni, Tomaso Concerto Pour 2 Trompettes in C; Concerto in C (Lionel Andre, trumpet) (also works by Tartini; Vivaldi; Maurice André, trumpet) 1520 Alderete, Ignacio: Harpe indienne et orgue 1019 Aloft: Heritage of America Band (United States Air Force/Captain Larry H. -

Mahler 5 & Music You Know

CONCERT PROGRAM Friday, January 22, 2016, 10:30am Saturday, January 23, 2016, 8:00pm David Robertson, conductor Timothy McAllister, saxophone JOHN ADAMS Saxophone Concerto (2013) (b. 1947) Animato; Moderato; Tranquillo, suave Molto vivo (a hard driving pulse) Timothy McAllister, saxophone INTERMISSION MAHLER Symphony No. 5 in C-sharp minor (1901-02) (1860-1911) PART I Trauermarsch. In gemessenem Schritt. Streng. Wie ein Kondukt Stürmisch bewegt, mit größter Vehemenz PART II Scherzo. Kräftig, nicht zu schnell PART III Adagietto. Sehr langsam— Rondo-Finale. Allegro 23 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These concerts are part of the Wells Fargo Advisors Orchestral series. These concerts are presented by St. Louis College of Pharmacy. David Robertson is the Beofor Music Director and Conductor. Timothy McAllister is the Ann and Paul Lux Guest Artist. The concert of Saturday, January 23, is underwritten in part by a generous gift from Rex and Jeanne Sinquefield. The concert of Friday, January 22, 10:30am, features coffee and doughnuts provided through the generosity of Community Coffee and Krispy Kreme, respectively. Pre-Concert Conversations are sponsored by Washington University Physicians. Large print program notes are available through the generosity of Bellefontaine Cemetery and Arboretum and are located at the Customer Service table in the foyer. 24 ON EDGE BY EDDIE SILVA Their music is made of the worlds around them, Gustav Mahler and John Adams. Mahler of that thrilling age, the shift from the 19th to the 20th century, the speed of the modern beginning to TIMELINKS change how people think and act. Also a time of anxiety, especially for a Jewish artist in an anti- Semitic Vienna. -

Download Booklet

Acknowledgments This recording was made at the I would also like to thank the Teresa This disc is dedicated to all the Academy of Arts and Letters in Sterne Foundation, Gilbert Kalish, members of my family — especially Manhattan, New York on May and Norma Hurlburt for their gener- my mom, dad, Eve, Henry, and 26-28, 2007. Thank you to osity, which helped to make this my nephews — who have been a Ardith Holmgrain for her help disc a reality. And, a thank you to constant source of love and support in arranging our use of this Lehman College and its Shuster in my life; to my primary teachers magnificent recording space. Grant through the Research Jesslyn Kitts, Michael Zenge, Foundation of the City of New Leonard Hokanson, and Gilbert I would like to thank Max Wilcox, York for their help in the Kalish; to a cherished circle of who very graciously helped to completion of this disc. friends, which grows wider all the prepare and record this disc. time; and, to God who orchestrated Without his help it never could I would also like to thank Jeremy all of these parts. have happened. I also thank Mary Geffen, Ara Guzelemian, Kathy Schwendeman for the use of her Schumann, John Adams, Peter glorious Steinway. Thank you to Sellars, David Robertson, Dawn David Merrill who continuously Upshaw and the Carnegie Hall Publishers: t h r e a d s offered a bright smile and encour- family for giving me so many Andriessen: Boosey & Hawkes aging words during the engineering wonderfully rich treasures in my Music Publishers Limited and recording of this disc and musical experiences thus far. -

THE CLEVELAN ORCHESTRA California Masterwor S

����������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ �������������������������������������� �������� ������������������������������� ��������������������������� ��������������������������������������������������� �������������������� ������������������������������������������������������� �������������������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������ ������������������������������������������������� ���������������������������� ����������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������������ ���������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������������������������� ���������������������������������������� ��������� ������������������������������������� ���������� ��������������� ������������� ������ ������������� ��������� ������������� ������������������ ��������������� ����������� �������������������������������� ����������������� ����� �������� �������������� ��������� ���������������������� Welcome to the Cleveland Museum of Art The Cleveland Orchestra’s performances in the museum California Masterworks – Program 1 in May 2011 were a milestone event and, according to the Gartner Auditorium, The Cleveland Museum of Art Plain Dealer, among the year’s “high notes” in classical Wednesday evening, May 1, 2013, at 7:30 p.m. music. We are delighted to once again welcome The James Feddeck, conductor Cleveland Orchestra to the Cleveland Museum of Art as this groundbreaking collaboration between two of HENRY COWELL Sinfonietta -

Microsoft Outlook

Dave M. Peck From: Squidco <[email protected]> Sent: Thursday, September 14, 2017 10:11 AM To: Dave M. Peck Subject: SQUIDCO Email Update September 14, 2017 UPDATE September 14, 2017 We wanted to make a new art— new expressions of art— in an art world that was, for us, traditional." —Herman Nitsch Essential Labels Alga Marghen KARLRECORDS Art Yard Matchless Clang Mikroton Recordings Confront Room40 Creative Sources Someone Good / Room40 Discus Taping Policies Evil Clown Trost Records Fragment Factory Wide Hive Holidays Records Creative Artists 1 • Abecassis, Eryck / Francisco Meirino • Derek Bailey / Mick Beck / Paul Hession • Borbetomagus • Tony Buck • Deep Tide Quartet (Archer / Macari / Cole / Shaw) • The Elks (Fagaschinski/Allbee/Roisz/Zapparoli) • Georg Graewe / Mark Sanders • Haco • Junk & The Beast (Petr Vrba / Veronika Mayer) • Alice Kemp • Leap of Faith • Kurt Liedwart • Roscoe Mitchell • Dafna Naphtali / Gordon Beeferman • Hermann Nitsch • Orfeo 5 (Blezard/Bourne/Jafrate w/ Prince/Oliver/Kane) • Charlemagne Palestine • Pat Patrick And The Baritone Saxophone Retinue • Massimo Pupillo / Alexandre Babel / Caspar Brotzmann • Ernesto Rodrigues / Ulrike Brand / Olaf Rupp • Sakata / Mota / Di Domenico / Calleja • Udo Schindler • String Theory [Boston, USA] • String Theory [PORTUGAL] • Eckard Vossas 4 (Vossas / Fields / Henkel / Nabatov) • Christian Wolfarth / Jason Kahn • Christian Wolff / Eddie Prevost • Nate Wooley / Daniele Martini / Joao Lobo • Zeitkratzer / Svetlana Spajic/Dragana Tomic/Obrad Milic • Zeitkratzer + Elliott Sharp Jazz & Improvisation Bailey, Derek / Mick Beck / Paul Hession: Meanwhile, Back In Sheffield... (Discus) Free improvising guitar legend Derek Bailey was invited to perform in his home town of Sheffield, England in 2004 with the trio of Mick Beck on tenor sax, bassoon, and whistles, and Paul Hession on drums, Bailey's first visit in many years, and a joyful occasion as the collective group explores a wide range of approaches to creating instant compositions. -

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #Bamnextwave

2018 BAM Next Wave Festival #BAMNextWave Brooklyn Academy of Music Adam E. Max, Katy Clark, Chairman of the Board President William I. Campbell, Joseph V. Melillo, Vice Chairman of the Board Executive Producer Place BAM Harvey Theater Oct 11—13 at 7:30pm; Oct 13 at 2pm Running time: approx. one hour 15 minutes, no intermission Created by Ted Hearne, Patricia McGregor, and Saul Williams Music by Ted Hearne Libretto by Saul Williams and Ted Hearne Directed by Patricia McGregor Conducted by Ted Hearne Scenic design by Tim Brown and Sanford Biggers Video design by Tim Brown Lighting design by Pablo Santiago Costume design by Rachel Myers and E.B. Brooks Sound design by Jody Elff Assistant director Jennifer Newman Co-produced by Beth Morrison Projects and LA Phil Season Sponsor: Leadership support for music programs at BAM provided by the Baisley Powell Elebash Fund Major support for Place provided by Agnes Gund Place FEATURING Steven Bradshaw Sophia Byrd Josephine Lee Isaiah Robinson Sol Ruiz Ayanna Woods INSTRUMENTAL ENSEMBLE Rachel Drehmann French Horn Diana Wade Viola Jacob Garchik Trombone Nathan Schram Viola Matt Wright Trombone Erin Wight Viola Clara Warnaar Percussion Ashley Bathgate Cello Ron Wiltrout Drum Set Melody Giron Cello Taylor Levine Electric Guitar John Popham Cello Braylon Lacy Electric Bass Eileen Mack Bass Clarinet/Clarinet RC Williams Keyboard Christa Van Alstine Bass Clarinet/Contrabass Philip White Electronics Clarinet James Johnston Rehearsal pianist Gareth Flowers Trumpet ADDITIONAL PRODUCTION CREDITS Carolina Ortiz Herrera Lighting Associate Lindsey Turteltaub Stage Manager Shayna Penn Assistant Stage Manager Co-commissioned by the Los Angeles Phil, Beth Morrison Projects, Barbican Centre, Lynn Loacker and Elizabeth & Justus Schlichting with additional commissioning support from Sue Bienkowski, Nancy & Barry Sanders, and the Francis Goelet Charitable Lead Trusts. -

Lucie Vítková (1985, Boskovice, CZ); +1 347 967 2997; [email protected];

Lucie Vítková (1985, Boskovice, CZ); +1 347 967 2997; [email protected]; http://www.vitkovalucie.com. I am a composer, performer and improviser of accordion, harmonica, voice and dance from the Czech Republic. My work pursues two lines of enquiry: my compositional practice focuses on sonification (compositions based on abstract models derived from physical objects), while my improvisational practice explores characteristics of discrete spaces through the interaction between sound and movement. Recently, I have become particularly interested in the question of social relationships in music and their implications for the structural organization of musical pieces. I explore this theme in all aspects of my work. Education: [2013-present] Janacek Academy of Music and Performing Arts Brno (JAMU Brno), CZ: Doctorate in composition and music theory (Ph.D.) with Peter Graham; in the academic year 2014/2015 recipient of Nadace Český hudební fond scholarship. [1/2016-1/2017] Columbia University NYC, USA: Visiting scholar with Prof. George E. Lewis. [2/2015-12/2015] Universität der Künste Berlin, DE: Recipient of Erasmus Scholarship for studies in composition and music theory with Marc Sabat. [9/2014-1/2015] Universität der Künste Berlin: Recipient of DAAD scholarship (Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst). [2011-13] JAMU Brno: Master’s Degree (MgA.) in composition with Martin Smolka and Peter Graham, including the following international exchanges: [2011-12] Royal Conservatoire The Hague, NL: Recipient of Erasmus Scholarship for studies in composition with Martijn Padding, Cornelis de Bondt, Gilius van Bergeijk and Yannis Kyriakides, and in sonology (a subset of sound studies) with Paul Berg, Joel Ryan, Peter Pabon, Richard Barrett and Kees Tazelaar. -

Making Your Classroom Go

teaching OCTOBER 2015 VOLUME 23, NUMBER 2 A SMALL Makingmusicmusic Your BUT Classroom Go MIGHTY Music How to Program engage your students with the music “POP” of today TEACHING SINGERS to Sight-Read The Elementary and Secondary EDUCATION ACT QuaverFindOutAd_NAfME_Aug15.pdf 1 7/30/15 12:26 PM Find out what these districts already know... Quaver is revolutionizing music education! TM C M Y CM MY CY CMY K Packed with nearly 1,000 Songs! Try 36 Lessons from our K-8 Curriculum! Just go to QuaverMusic.com/Preview and begin your FREE 30-day trial today! ©2015 QuaverMusic.com, LLC October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 contentsMUSIC EDUCATION ● ORCHESTRATING SUCCESS Music students learn cooperation, discipline, and teamwork. 28 Teachers and students alike can rock out and learn with pop music! FEATURES 24 TEACHING SINGERS 28 POP AND ROCK GOES 32 EL SISTEMA TODAY 38 SMALL SCHOOL, TO READ THE PROGRAM! José Antonio Abreu’s BIG EFFORT, Instructing students in Pop music connects creation has taken GREAT SUCCESS the art and techniques instantly with many root in the U.S. and Alexandria Hanessian’s of sight-singing can reap students. How can continues to grow small but mighty middle many rewards in your music educators use through programs such school program thrives choral rehearsals and it in their classrooms as the Corona Youth in Spencertown, beyond. to increase student Music Project and New York. engagement? Juneau Alaska Music Matters. Photo by Little Kids Rock. Photo by nafme.org 1 October 2015 Volume 23, Number 2 Student composers contents (far left and right) work with teachers Conductor Marin Alsop 56 at Williamsville East works with students in High School. -

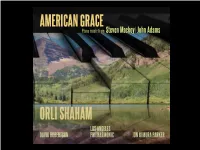

ORLI SHAHAM LOS ANGELES DAVID ROBERTSON PHILHARMONIC JON KIMURA PARKER 1 Merican Composers Have Always Pushed Boundaries, As Americans Themselves Have a Pushed West

AMERICAN GRACE Piano music from Steven Mackey | John Adams ORLI SHAHAM LOS ANGELES DAVID ROBERTSON PHILHARMONIC JON KIMURA PARKER 1 merican composers have always pushed boundaries, as Americans themselves have A pushed West. I feel strongly that John Adams and Steven Mackey are at the forefront of defining what it means to be an American pianist today. On a stunning summer’s day in 2007 in the inspiring Rocky Mountain valley of Aspen, I found myself as usual underground, in a windowless practice room. One of the magical things about Aspen is that the otherwise oppressive quality of such a room is transformed by the people who inhabit it. I was taking a practice break from Gershwin and Stravinsky, preparing for rehearsal with the orchestra, when Steve Mackey came off the stage from rehearsing his guitar concerto Tuck and Roll. I was seven months pregnant with my twin sons, and Steve and I immediately started to talk about both music and child-bearing, which his wife was soon to do as well. I relished our talk and was further enthralled by Steve’s sizzling guitar playing and magnetic compositional style. For the next months, I ravenously listened to his oeuvre, convincing me that he was the first composer I wanted to ask to write me a concerto. The process was amazing. Steve showed me bits now and again, listened to my recordings and live performances, asked about my hand size, even allowed me a say in the final dramatic turn of the piece. Every time a part of the score came my way, I was more excited to learn it and understand it. -

The Challenge of African Art Music Le Défi De La Musique Savante Africaine Kofi Agawu

Document generated on 09/27/2021 1:07 p.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines The Challenge of African Art Music Le défi de la musique savante africaine Kofi Agawu Musiciens sans frontières Article abstract Volume 21, Number 2, 2011 This essay offers broad reflection on some of the challenges faced by African composers of art music. The specific point of departure is the publication of a URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1005272ar new anthology, Piano Music of Africa and the African Diaspora, edited by DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Ghanaian pianist and scholar William Chapman Nyaho and published in 2009 by Oxford University Press. The anthology exemplifies a diverse range of See table of contents creative achievement in a genre that is less often associated with Africa than urban ‘popular’ music or ‘traditional’ music of pre-colonial origins. Noting the virtues of musical knowledge gained through individual composition rather than ethnography, the article first comments on the significance of the Publisher(s) encounters of Steve Reich and György Ligeti with various African repertories. Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Then, turning directly to selected pieces from the anthology, attention is given to the multiple heritage of the African composer and how this affects his or her choices of pitch, rhythm and phrase structure. Excerpts from works by Nketia, ISSN Uzoigwe, Euba, Labi and Osman serve as illustration. 1183-1693 (print) 1488-9692 (digital) Explore this journal Cite this article Agawu, K. (2011). The Challenge of African Art Music. Circuit, 21(2), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.7202/1005272ar Tous droits réservés © Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal, 2011 This document is protected by copyright law.