Operability, Usefulness, and Task-Technology Fit of an Mhealth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Impact of Aga Khan Rural Support Program's Gender Strategy On

Impact of Aga Khan Rural Support Program’s Gender Strategy on Rural Women in District Chitral Rabia Gul Allama Iqbal Open University Islamabad Email: [email protected] Abstract The study was conducted in Chitral Valley in the North of Pakistan to explore the gender related activities introduced by the Aga Khan Rural Support Program (AKRSP).The findings show that the AKRSP has been playing a key role in the development of women in the area and initiated development programs in water supply, health and credit facilities. It imparted trainings for the local women in different disciplines through the Women Organizations (WO’s) established in the area. These trainings were recorded and mostly repeated via video cassettes in different villages. Posters and charts were also used to make the trainings easier for the local women to understand. The AKRSP has also been successful to take few hours daily from the Local Government Radio in the area and communicate to the women in their local language about certain issues such as personal hygiene, procedure to get and pay back loans from the micro finance bank of AKRSP, about agricultural practices etc. Practical adoption of these trainings has made positive effect in the lives of the local women in terms of improved agricultural products and increase in income of the respondents. Further, the AKRSP is looking into the possibility of establishing a Community Radio which if established will play a major role for the development of the area. Thus, it is concluded that the AKRSP has made invaluable contributions in improving the access of women to education, health resources and economic empowerment opportunities. -

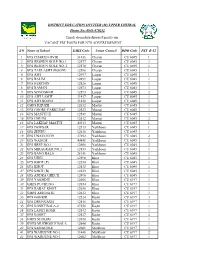

S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1

DISTRICT EDUCATION OFFICER (M) UPPER CHITRAL Phone No: 0943-470252 Email: [email protected] VACANT PST POSTS FOR NTS ADVERTISEMENT S.# Name of School EMIS Code Union Council DDO Code PST B-12 1 GPS CHARUN OVIR 31436 Charun CU 6045 1 2 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO.1 12577 Charun CU 6045 1 3 GPS RESHUN GOLE NO..2 12578 Charun CU 6045 1 4 GPS TAKLASHT (BOONI) 12596 Charun CU 6045 1 5 GPS AWI 12497 Laspur CU 6045 1 6 GPS BALIM 12499 Laspur CU 6045 1 7 GPS HERCHIN 12526 Laspur CU 6045 1 8 GPS RAMAN 12573 Laspur CU 6045 1 9 GPS SONOGHUR 12593 Laspur CU 6045 2 10 GPS AWI LASHT 31437 Laspur CU 6045 1 11 GPS AWI BOONI 31438 Laspur CU 6045 1 12 GMPS KHUZH 12632 Mastuj CU 6045 1 13 GPS GHORU PARKUSAP 12523 Mastuj CU 6045 1 14 GPS MASTUJ II 12549 Mastuj CU 6045 1 15 GPS CHUINJ 12512 Mastuj CU 6045 2 16 GPS LAKHAP MASTUJ 40313 Mastuj CU 6045 1 17 GPS DEWSAR 12513 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 18 GPS ZHUPU 12610 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 19 GPS UNAVOUCH 37292 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 20 GPS WASUM 40841 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 21 GPS BREP NO.1 12508 Yarkhoon CU 6045 2 22 GPS MIRAGRAM NO.2 12553 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 23 GPS BANG BALA 28141 Yarkhoon CU 6045 1 24 GPS UJNU 12598 Khot CU 6045 1 25 GPS KHOT (P) 12534 Khot CU 6045 1 26 GPS KHOT 12532 Khot CU 6045 1 27 GPS KHOT (B) 12533 Khot CU 6045 1 28 GPS ANDRA GHECH 12496 Khot CU 6045 1 29 GPS YAKHDIZ 12606 Khot CU 6197 1 30 GMPS PUCHUNG 12654 Khot CU 6197 1 31 GPS RABAT KHOT 12656 Khot CU 6197 1 32 GMPS AMUNATE 12612 Khot CU 6197 1 33 GPS GOHKIR 12524 Kosht CU 6197 3 34 GPS DRUNGAGH 12516 Kosht CU 6197 1 35 GPS KOSHT BALA-2 27550 Kosht -

Language Documentation and Description

Language Documentation and Description ISSN 1740-6234 ___________________________________________ This article appears in: Language Documentation and Description, vol 17. Editor: Peter K. Austin Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan ZUBAIR TORWALI Cite this article: Torwali, Zubair. 2020. Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan. In Peter K. Austin (ed.) Language Documentation and Description 17, 44- 65. London: EL Publishing. Link to this article: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/181 This electronic version first published: July 2020 __________________________________________________ This article is published under a Creative Commons License CC-BY-NC (Attribution-NonCommercial). The licence permits users to use, reproduce, disseminate or display the article provided that the author is attributed as the original creator and that the reuse is restricted to non-commercial purposes i.e. research or educational use. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing For more EL Publishing articles and services: Website: http://www.elpublishing.org Submissions: http://www.elpublishing.org/submissions Countering the challenges of globalization faced by endangered languages of North Pakistan Zubair Torwali Independent Researcher Summary Indigenous communities living in the mountainous terrain and valleys of the region of Gilgit-Baltistan and upper Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, northern -

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera

Survey of Predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Author(s): Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi Source: Journal of Insect Science, 7(7):1-6. 2007. Published By: Entomological Society of America DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1673/031.007.0701 URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1673/031.007.0701 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Journal of Insect Science | www.insectscience.org ISSN: 1536-2442 Survey of predatory Coccinellids (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) in the Chitral District, Pakistan Inamullah Khan, Sadrud Din, Said Khan Khalil and Muhammad Ather Rafi1 Department of Plant Protection, NWFP Agricultural University, Peshawar, Pakistan 1 National Agricultural Research Council, Islamabad, Pakistan Abstract An extensive survey of predatory Coccinellid beetles (Coleoptera: Coccinellidae) was conducted in the Chitral District, Pakistan, over a period of 7 months (April through October, 2001). -

Pdf 325,34 Kb

(Final Report) An analysis of lessons learnt and best practices, a review of selected biodiversity conservation and NRM projects from the mountain valleys of northern Pakistan. Faiz Ali Khan February, 2013 Contents About the report i Executive Summary ii Acronyms vi SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION 1 1.1. The province 1 1.2 Overview of Natural Resources in KP Province 1 1.3. Threats to biodiversity 4 SECTION 2. SITUATIONAL ANALYSIS (review of related projects) 5 2.1 Mountain Areas Conservancy Project 5 2.2 Pakistan Wetland Program 6 2.3 Improving Governance and Livelihoods through Natural Resource Management: Community-Based Management in Gilgit-Baltistan 7 2.4. Conservation of Habitats and Species of Global Significance in Arid and Semiarid Ecosystem of Baluchistan 7 2.5. Program for Mountain Areas Conservation 8 2.6 Value chain development of medicinal and aromatic plants, (HDOD), Malakand 9 2.7 Value Chain Development of Medicinal and Aromatic plants (NARSP), Swat 9 2.8 Kalam Integrated Development Project (KIDP), Swat 9 2.9 Siran Forest Development Project (SFDP), KP Province 10 2.10 Agha Khan Rural Support Programme (AKRSP) 10 2.11 Malakand Social Forestry Project (MSFP), Khyber Pakhtunkhwa 11 2.12 Sarhad Rural Support Program (SRSP) 11 2.13 PATA Project (An Integrated Approach to Agriculture Development) 12 SECTION 3. MAJOR LESSONS LEARNT 13 3.1 Social mobilization and awareness 13 3.2 Use of traditional practises in Awareness programs 13 3.3 Spill-over effects 13 3.4 Conflicts Resolution 14 3.5 Flexibility and organizational approach 14 3.6 Empowerment 14 3.7 Consistency 14 3.8 Gender 14 3.9. -

Current Scenario and Threats to Ichthyo-Diversity in the Foothills of Hindu Kush: Addition to the Checklist of Coldwater Fishes of Pakistan

Pakistan J. Zool., vol. 48(1), pp. 285-288, 2016. Short Communication Current Scenario and Threats to Ichthyo-Diversity in the Foothills of Hindu Kush: Addition to the Checklist of Coldwater Fishes of Pakistan Arif Jan,* Abdul Rab, Rooh Ullah, Hussain Shah, Haroon, Iftikhar Ahmad, Muhammad Younas and Ikram Ullah Department of Zoology, Shaheed Benazir Bhutto University, Sheringal, Dir Upper. Article Information Received 16 January 2015 A B S T R A C T Revised 9 August 2015 Accepted 19 September 2015 Chitral, the pinnacle of Hindu Kush, draining 31 notable glaciers, is least studied for Ichthyo-faunal Available online 1 January 2016 diversity. This work explored the fish fauna and the risk factors for the Ichthyo-faunal diversity loss Authors’ Contributions at the foothills of Hindu Kush. A total of 21 fish species were collected from different parts and AJ has conducted the field work, tributaries of River Chitral, from Shandur up to Arandu, extending to Afghanistan border. Our analyzed the data and wrote the collection reported 4 fish species for the first time from Pakistan, namely Acanthocobitis article. HS, H and IA helped in the uropthalmus, Lepidopygnosis typus, Horalabiosa palaniensis, Horalabiosa joshuai. One species field work arrangements. MY, RU namely Nangra robusta is reported for the first time from River Chitral. Alluvial nature of rocks, and IU helped in literature search. construction of hydro projects and duck ponds, introduction of exotic species, erosion and AR helped in identification. sedimentation of rivers and streams, illegal fishing, and effluent discharges are the major concerns. Major threats to biodiversity loss need to be addressed for proper conservation of biodiversity as a Key words whole and Ichthyo-diversity in particular. -

Chitral Case Study April 26.Inddsec2:24 Sec2:24 4/27/2007 1:38:17 PM C H I T R a L

Chapter 3 Observing and Experiencing Flash Floods ocal knowledge on disaster preparedness in the Chitral the mountains. […] The fl ood blocked the river for 10 minutes District of Pakistan includes aspects related to people’s and it became a big lake and destroyed a water mill. The fl ood Lobservation and experience of fl ash fl oods, anticipation of continued until 9 pm. Some big stones are still stuck inside the fl oods, adjustment strategies, and communication strategies. valley.” (Narrated by Islamuddin, Aziz Urahman, Gul Muhammad Jan, Rashidullah, Khan Zarin and Ghulam Jafar, Gurin village, The people of Chitral have knowledge about the history and Gurin Gole, Shishi Koh valley, Lower Chitral) nature of fl ash fl oods in their own locality based on daily observation of their local surroundings, close ties to their “We were ready to take our goats up to the higher pastures environment for survival, and an accumulated understanding when eight days of discontinuous heavy rain fell from June 30th of their environment through generations. They have learned till July 9th 1978. We shifted our animals and family members to interpret their landscape and the physical indicators of past during that period to a nearby village. On July 7th, the river fl ash fl oods. They can also describe and explain how their own started to build up in the main course and to spill over. Some vulnerability to fl oods has changed over time. houses were destroyed. On July 9th even more houses were destroyed. The main fl ow came during the night of July 9th”. -

Debris Flow Hazard in Chitral

Landform Control on Debris Flow Hazards Hindukush Himalayas Chitral District, N. Pakistan M. Asif Khan & M. Haneef National Centre of Excellence in Geology University of Peshawar Pakistan Objectives: • Identify Debris Flow Hazards on Alluvial Fan Landforms Approaches: • Satellite Images and Field Observations • Morphometric Analysis of Drainage vs Depositional Basins Outcomes: • Develop Understanding of Debris Flow Processes for General Awareness & Mitigation through Engineering Solutions 2 Chitral District, Hindukush Range • Physiography • Habitats • Natural Hazards Quaternary Landforms Mass Movement Landforms • Types • Controlling Tributary Streams • Morphometery Landform Control on Debris Flow Hazards Kohistan N Tibet Himalayas Chitral R. Pamir Knot Hindu Kush 4 Pamirs CHITRAL 5 Physiography •Eastern Hindukush 5500-7500 m high (Tirich Mir Peak 7706 m) Climate •Hindu Raj 5000-7000 m high •34% are above 4500 m asl, with 10% under permanent snow cover •Minimum altitude 1070 m at Arandu. •Relief ranges from 3200 to 6000 m at the eastern face of the Tirich Mir. Climate •high-altitude continental, classified as arid to semi-arid 6 CHITRAL 7 Hindu Raj Chitral Valley Tirich Mir (5706 m) SE NW 8 Upper Chitral Valley, N. Pakistan N 9 10 11 DEBRIS FLOW HAZARD Venzuella Debris Flow- 1999 Deaths: 50,000 Persons affected: 331,164 Homeless: 250,000 Disappeared persons: 7,200 Housing units affected: 63,935 Housing units destroyed: 23,234 12 13 Debris Flow Hazards Settings in Chitral Habitation restricted to River-Bank Terraces Terraced Landforms Flood Plain Recent Alluvial/Debris Fans Remnants of Glacial Moraines Remnant Inter-glacial and Post- Glacial Alluvial fans Chitral R. Recent Debris Flow BUNI 14 N Bedrock Lithologies: PF Purit Fm (S.St; Congl,Shale) DF Drosh Fm (Green Schist) MZ Mélange Zone (Ultramafic blocks, AF6 volcanic rocks, slate) Alluvial Fan Terraces AFT-1-4 Remnant Fans AFT-5,6 Active Fans LFT Lake sediment Terraces Multi-Stage Landform Terraces, Drosh, Chitral, Pakistan 15 Classification of Landforms, Chitral, N. -

Parcel Post Compendium Online Pakistan Post PKA PK

Parcel Post Compendium Online PK - Pakistan Pakistan Post PKA Basic Services CARDIT Carrier documents international Yes transport – origin post 1 Maximum weight limit admitted RESDIT Response to a CARDIT – destination Yes 1.1 Surface parcels (kg) 50 post 1.2 Air (or priority) parcels (kg) 50 6 Home delivery 2 Maximum size admitted 6.1 Initial delivery attempt at physical Yes delivery of parcels to addressee 2.1 Surface parcels 6.2 If initial delivery attempt unsuccessful, Yes 2.1.1 2m x 2m x 2m No card left for addressee (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 6.3 Addressee has option of paying taxes or Yes 2.1.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes duties and taking physical delivery of the (or 3m length & greatest circumference) item 2.1.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 6.4 There are governmental or legally (or 2m length & greatest circumference) binding restrictions mean that there are certain limitations in implementing home 2.2 Air parcels delivery. 2.2.1 2m x 2m x 2m No 6.5 Nature of this governmental or legally (or 3m length & greatest circumference) binding restriction. 2.2.2 1.5m x 1.5m x 1.5m Yes (or 3m length & greatest circumference) 2.2.3 1.05m x 1.05m x 1.05m No 7 Signature of acceptance (or 2m length & greatest circumference) 7.1 When a parcel is delivered or handed over Supplementary services 7.1.1 a signature of acceptance is obtained Yes 3 Cumbersome parcels admitted No 7.1.2 captured data from an identity card are Yes registered 7.1.3 another form of evidence of receipt is No Parcels service features obtained 5 Electronic exchange of information -

A Remote Sensing Contribution to Flood Modelling in an Inaccessible

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 29 October 2018 doi:10.20944/preprints201810.0650.v1 1 Type of the Paper (Article) 2 A Remote Sensing Contribution to Flood Modelling 3 in an Inaccessible Mountainous River Basin 4 Alamgeer Hussain1, Jay Sagin2*, Kwok P. Chun3 5 1 Secretariat of Agriculture, Livestock and Fisheries Department, Gilgit Baltistan, Pakistan 6 2Nazarbayev University, 53 Kabanbay Batyr Avenue, Astana, 010000, Kazakhstan 7 3Hong Kong Baptist University, Baptist University Rd, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong 8 9 * Correspondence: [email protected]; WhatsApp: +7-702-557-2038, +1-269-359-5211 10 11 Abstract: Flash flooding, a hazard which is triggered by heavy rainfall is a major concern in many 12 regions of the world often with devastating results in mountainous elevated regions. We adapted 13 remote sensing modelling methods to analyse one flood in July 2015, and believe the process can be 14 applicable to other regions in the world. The isolated thunderstorm rainfall occurred in the Chitral 15 River Basin (CRB), which is fed by melting glaciers and snow from the highly elevated Hindu Kush 16 Mountains (Tirick Mir peak’s elevation is 7708 m). The devastating cascade, or domino effect, 17 resulted in a flash flood which destroyed many houses, roads, and bridges and washed out 18 agricultural land. CRB had experienced devastating flood events in the past, but there was no 19 hydraulic modelling and mapping zones available for the entire CRB region. That is why modelling 20 analyses and predictions are important for disaster mitigation activities. For this flash flood event, 21 we developed an integrated methodology for a regional scale flood model that integrates the 22 Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite, Geographic Information System (GIS), 23 hydrological (HEC-HMS) and hydraulic (HEC-RAS) modelling tools. -

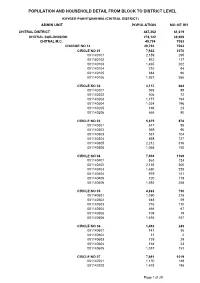

Chitral Blockwise

POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH CHITRAL DISTRICT 447,362 61,619 CHITRAL SUB-DIVISION 278,122 38,909 CHITRAL M.C. 49,794 7063 CHARGE NO 14 49,794 7063 CIRCLE NO 01 7,933 1070 001140101 2,159 295 001140102 972 117 001140103 1,465 202 001140104 716 94 001140105 684 96 001140106 1,937 266 CIRCLE NO 02 4,157 664 001140201 593 89 001140202 505 72 001140203 1,171 194 001140204 1,024 196 001140205 198 23 001140206 666 90 CIRCLE NO 03 5,875 878 001140301 617 85 001140302 569 96 001140303 551 104 001140304 858 127 001140305 2,212 316 001140306 1,068 150 CIRCLE NO 04 7,939 1169 001140401 863 124 001140402 2,135 300 001140403 1,650 228 001140404 979 141 001140405 720 118 001140406 1,592 258 CIRCLE NO 05 4,883 730 001140501 1,590 218 001140502 448 59 001140503 776 110 001140504 466 67 001140505 109 19 001140506 1,494 257 CIRCLE NO 06 1,492 243 001140601 141 36 001140602 11 2 001140603 139 29 001140604 164 23 001140605 1,037 153 CIRCLE NO 07 7,691 1019 001140701 1,170 149 001140702 1,478 195 Page 1 of 29 POPULATION AND HOUSEHOLD DETAIL FROM BLOCK TO DISTRICT LEVEL KHYBER PAKHTUNKHWA (CHITRAL DISTRICT) ADMIN UNIT POPULATION NO OF HH 001140703 1,144 156 001140704 1,503 200 001140705 1,522 196 001140706 874 123 CIRCLE NO 08 9,824 1290 001140801 2,779 319 001140802 1,605 240 001140803 1,404 200 001140804 1,065 152 001140805 928 124 001140806 974 135 001140807 1,069 120 CHITRAL TEHSIL 228,328 31846 ARANDU UC 23,287 3105 AKROI 1,777 301 001010105 1,777 301 ARANDU -

Extension of AKRSP Activities to Chitral. May 3, 1983 1100-1330

May 3-5, 1983 NOTE FOR THE RECORD Subject: Extension of AKRSP activities to Chitral. May 3, 1983 1100-1330 hours Drosh Tehsil Headquarters 1430-1530 hours Village Gabur in Lotkoh Valley. 1730-1900 hours District Council, Chitral. May 4, 1983 1000 hours Meeting with Commissioner, Malakand Division and district administration officials. 1700 hours Reception at the palace of Mehtar of Chitral. May 5, 1983 0745 hours Left Chitral by helicopter via Shandur Pass 0935 hours Arrived Gilgit Participants: In the meetings, discussions and visits included the: - Commissioner Malakand Division - DIG (Police), Malakand Division - Deputy Commissioner, Chitral - SP Chitral - Commandant Chitral Scouts - District Councilors of Chitral - Chairmen and Members of Drosh Union Councils and villagers of Gabur - Mr. Latif Hasan, Chairman District Council Gilgit accompanied GM AKRSP and - Mr. Robert d'Arcy Shaw, Director of Special Programmes, AKF Geneva. The visit to Chitral like the visit in April 1983 had to be postponed from May 2 to 3, 1983 due to non- availability of helicopter. However, the Commissioner Malakand Division was informed of the change well in time and was saved of the inconvenience of waiting at the Kabal airport for the helicopter as he had to do along with the Additional Chief Secretary (P&D), last time. At Kabal airport, Mr. Shamsher Ali Khan, Commissioner Malakand Division along with Mr. Khurshid, Acting DIG Police boarded the helicopter for onward journey to Chitral. I the meeting at Drosh tehsil nearly 40 Chairmen and Member of the UCs participated besides the officials.The Commissioner briefly introduced the programme and GM elucidated the aims and objectives of AKRSP.