Whitechapel Gallery Art Icon 2021

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mapping Artists' Professional Development Programmes in the Uk: Knowledge and Skills

1 REBECCA GORDON-NESBITT FOR CHISENHALE GALLERY SUPPORTED BY PAUL HAMLYN FOUNDATION MARCH 2015 59 PAGES MAPPING ARTISTS’ PROFESSIONAL DEVELOPMENT PROGRAMMES IN THE UK: KNOWLEDGE AND SKILLS 2 COLOPHON Mapping Artists’ Professional Development This research was conducted for Chisenhale Programmes in the UK: Knowledge and Skills Gallery by Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt with funding from Paul Hamlyn Foundation. Author: Rebecca Gordon-Nesbitt Editors: Polly Staple and Laura Wilson → Chisenhale Gallery supports the production Associate Editor: Andrea Phillips and presentation of new forms of artistic delivery Producer: Isabelle Hancock and engages diverse audiences, both local and Research Assistants: Elizabeth Hudson and international. Pip Wallis This expands on our award winning, 32 year Proofreader: 100% Proof history as one of London’s most innovative forums Design: An Endless Supply for contemporary art and our reputation for Commissioned and published by Chisenhale producing important solo commissions with artists Gallery, London, March 2015, with support from at a formative stage in their career. Paul Hamlyn Foundation. We enable emerging or underrepresented artists to make significant steps and pursue Thank you to all the artists and organisational new directions in their practice. At the heart of representatives who contributed to this research; our programme is a remit to commission new to Regis Cochefert and Sarah Jane Dooley from work, supporting artists from project inception Paul Hamlyn Foundation for their advice and to realisation and representing an inspiring and support; and to Chisenhale Gallery’s funders, challenging range of voices, nationalities and art Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Arts Council England. forms, based on extensive research and strong curatorial vision. -

Anya Gallaccio

ANYA GALLACCIO Born Paisley, Scotland 1963 Lives London, United Kingdom EDUCATION 1985 Kingston Polytechnic, London, United Kingdom 1988 Goldsmiths' College, University of London, London, United Kingdom SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2019 NOW, The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh, Scotland Stroke, Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2018 dreamed about the flowers that hide from the light, Lindisfarne Castle, Northumberland, United Kingdom All the rest is silence, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, United Kingdom 2017 Beautiful Minds, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2015 Silas Marder Gallery, Bridgehampton, NY Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego, San Diego, CA 2014 Aldeburgh Music, Snape Maltings, Saxmundham, Suffolk, United Kingdom Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA 2013 ArtPace, San Antonio, TX 2011 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom Annet Gelink, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2010 Unknown Exhibition, The Eastshire Museums in Scotland, Kilmarnock, United Kingdom Annet Gelink Gallery, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2009 So Blue Coat, Liverpool, United Kingdom 2008 Camden Art Centre, London, United Kingdom 2007 Three Sheets to the wind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, United Kingdom 2006 Galeria Leme, São Paulo, Brazil One art, Sculpture Center, New York, NY 2005 The Look of Things, Palazzo delle Papesse, Siena, Italy Blum and Poe, Los Angeles, CA Silver Seed, Mount Stuart Trust, Isle of Bute, Scotland 2004 Love is Only a Feeling, Lehmann Maupin, New York, NY 2003 Love is only a feeling, Turner Prize Exhibition, -

Gallery Guide Is Printed on Recycled Paper

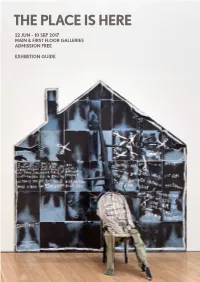

THE PLACE IS HERE 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN & FIRST FLOOR GALLERIES ADMISSION FREE EXHIBITION GUIDE THE PLACE IS HERE LIST OF WORKS 22 JUN – 10 SEP 2017 MAIN GALLERY The starting-point for The Place is Here is the 1980s: For many of the artists, montage allowed for identities, 1. Chila Kumari Burman blends word and image, Sari Red addresses the threat a pivotal decade for British culture and politics. Spanning histories and narratives to be dismantled and reconfigured From The Riot Series, 1982 of violence and abuse Asian women faced in 1980s Britain. painting, sculpture, photography, film and archives, according to new terms. This is visible across a range of Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper Sari Red refers to the blood spilt in this and other racist the exhibition brings together works by 25 artists and works, through what art historian Kobena Mercer has 78 × 190 × 3.5cm attacks as well as the red of the sari, a symbol of intimacy collectives across two venues: the South London Gallery described as ‘formal and aesthetic strategies of hybridity’. between Asian women. Militant Women, 1982 and Middlesbrough Institute of Modern Art. The questions The Place is Here is itself conceived of as a kind of montage: Lithograph and photo etching on Somerset paper it raises about identity, representation and the purpose of different voices and bodies are assembled to present a 78 × 190 × 3.5cm 4. Gavin Jantjes culture remain vital today. portrait of a period that is not tightly defined, finalised or A South African Colouring Book, 1974–75 pinned down. -

Stanley Kubrick's 18Th Century

Stanley Kubrick’s 18th Century: Painting in Motion and Barry Lyndon as an Enlightenment Gallery Alysse Peery Abstract The only period piece by famed Stanley Kubrick, Barry Lyndon, was a 1975 box office flop, as well as the director’s magnum opus. Perhaps one of the most sumptuous and exquisite examples of cinematography to date, this picaresque film effectively recreates the Age of the Enlightenment not merely through facts or events, but in visual aesthetics. Like exploring the past in a museum exhibit, the film has a painterly quality harkening back to the old masters. The major artistic movements that reigned throughout the setting of the story dominate the manner in which Barry Lyndon tells its tale with Kubrick’s legendary eye for detail. Through visual understanding, the once obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray becomes a captivating window into the past in a manner similar to the paintings it emulates. In 1975, the famed and monumental director Stanley Kubrick released his one and only box-office flop. A film described as a “coffee table film”, it was his only period piece, based on an obscure novel by William Makepeace Thackeray (Patterson). Ironically, his most forgotten work is now considered his magnum opus by critics, and a complete masterwork of cinematography (BFI, “Art”). A remarkable example of the historical costume drama, it enchants the viewer in a meticulously crafted vision of the Georgian Era. Stanley Kubrick’s film Barry Lyndon encapsulates the painting, aesthetics, and overall feel of the 18th century in such a manner to transform the film into a sort of gallery of period art and society. -

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and Works in London, UK

Michael Landy Born in London, 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Goldsmith's College, London, UK, 1988 Solo Exhibitions 2017 Michael Landy: Breaking News-Athens, Diplarios School presented by NEON, Athens, Greece 2016 Out Of Order, Tinguely Museum, Basel, Switzerland (Cat.) 2015 Breaking News, Michael Landy Studio, London, UK Breaking News, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2014 Saints Alive, Antiguo Colegio de San Ildefonso, Mexico City, Mexico 2013 20 Years of Pressing Hard, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Saints Alive, National Gallery, London, UK (Cat.) Michael Landy: Four Walls, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2011 Acts of Kindness, Kaldor Public Art Projects, Sydney, Australia Acts of Kindness, Art on the Underground, London, UK Art World Portraits, National Portrait Gallery, London, UK 2010 Art Bin, South London Gallery, London, UK 2009 Theatre of Junk, Galerie Nathalie Obadia, Paris, France 2008 Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK In your face, Galerie Paul Andriesse, Amsterdam, The Netherlands Three-piece, Galerie Sabine Knust, Munich, Germany 2007 Man in Oxford is Auto-destructive, Sherman Galleries, Sydney, Australia (Cat.) H.2.N.Y, Alexander and Bonin, New York, USA (Cat.) 2004 Welcome To My World-built with you in mind, Thomas Dane Gallery, London, UK Semi-detached, Tate Britain, London, UK (Cat.) 2003 Nourishment, Sabine Knust/Maximilianverlag, Munich, Germany 2002 Nourishment, Maureen Paley/Interim Art, London, UK 2001 Break Down, C&A Store, Marble Arch, Artangel Commission, London, UK (Cat.) 2000 Handjobs (with Gillian -

Hannah Black ‘Some Context’ 22 September – 10 December 2017

HANNAH BLACK ‘SOME CONTEXT’ 22 SEPTEMBER – 10 DECEMBER 2017 READING LIST A reading list of texts, books and articles has been compiled in collaboration with Hannah Black to accompany her exhibition, Some Context, at Chisenhale Gallery. This resource expands on ideas raised through Black’s new commission. Included is previous writing by Black, such as her publications Dark Pool Party (DOMINICA/Arcadia Missa, 2016) and Life, with Juliana Huxtable, (mumok, 2017); essays and books that provide reference and further context to the work; and a selection of writings by contributors to The Situation (2017). Abreu, M. A. (2017). Three Poems by Manuel Arturo Abreu. [online] The Believer Logger. Available at: https://logger.believermag.com/post/three-poems-by-manuel-arturo-abreu [Accessed 8 Sep. 2017]. Aima, R. (2017). Body Party: Hannah Black. Mousse Magazine, [online] (57). Available at: http://moussemagazine.it/rahel-aima-hannah-black-2017/ [Accessed 7 Sep. 2017]. Black, H. (2014). My Bodies. [video] Available at: https://vimeo.com/85906379 [Accessed 7 Sep. 2017]. Black, H. (2016). Apocalypse Tourism. [online] The Towner. Available at: http://www.thetowner.com/apocalypsetourism/ [Accessed 9 Sep. 2017]. Black, H. (2015). Long term effects. In: K. Williams, H. Black, R. Johnson, A. Zett, S. M Harrison and S. Kotecha, After the eclipse. [online] Available at: http://www.annazett.net/pdf/AFTER%20THE%20ECLIPSE.pdf [Accessed 7 Sep. 2017]. Black, H. (2015). Some of the police officers spent up to 10 years pretending to be people who had died. In: E. Ryan, ed., Oh wicked flesh!. London: South London Gallery. Black, H. (2016). [Readings] | A Kind of Grace, by Hannah Black | Harper’s Magazine. -

The Penthouses | Central Street, Clerkenwell EC1

www.east-central.london The Penthouses | Central Street, Clerkenwell EC1 Welcome to the East Central Penthouse Collection. Four 3 bedroom lateral apartments located on the upper most level of this stylish new Clerkenwell, EC1 development. Each zinc clad penthouse features spacious light filled open plan living, and private south facing terraces with uninterrupted Clerkenwell views. Specification and workmanship are of the highest quality. All penthouse interiors are designed and specified by Love Interiors and feature fitted wardrobes to master suites, high gloss kitchens by London designer Urban Myth and hotel style bathrooms and en-suites. 01 E C A beguiling combination of old and new, of Eclectic Clerkenwell tradition and progress, Clerkenwell lies at the heart of modern London. East Central offers the quintessential London life, with one foot in the elegant, bohemian tradition of Bloomsbury and one foot in the booming technological hub of Shoreditch. This state of the art development of stunning apartments and penthouses combines cutting edge contemporary architecture in its stone and glass design, with the effortless character of its historic EC1 location. Follow in the footsteps of Dickens, Lenin, Cromwell, of kings themselves, as you step into A Portrait of the Area 21st Century Clerkenwell living. 02 03 E C East London has a market tradition dating back to the 12th Century. Historic Whitecross Street market, located between Old Street and Barbican, is a highly acclaimed haven of street foods making it a favourite lunchtime venue. Aside from the many local markets, some of the most critically celebrated and popular restaurants in London are to be found within a short walk of Central Street. -

Student Handout Presenter: Dr Clare Taylor

Open Arts Objects http://www.openartsarchive.org/open-arts-objects Student handout Presenter: Dr Clare Taylor Yinka Shonibare, Nelson’s Ship in a Bottle, 2010, National Maritime Museum, London http://www.openartsarchive.org/resource/open-arts-object-yinka-shonibare-nelson%E2%80%99s-ship- bottle-2010 In this film Dr Clare Taylor looks at a work made by a living artist who works in London, Yinka Shonibare. The subject, materials, and sites she talks about all encourage students to think of their own individual, national and global identity in new ways. The work also turns on its head traditional ideas of a sculpture on a plinth, which often commemorate a person well known in their own time, and reverses ideas about what such a work should be made out of, using a range of materials rather than stone or metal. Before watching the film 1. What do the words ‘Nelson’, ‘message in a bottle’ and ‘Trafalgar Square’ mean to you? 2. What do you think this work represents? 3. What is it made out of? And how is it put together? Are the materials obvious at first glance? 1 4. What function do you think this work serves? After watching the film 1. What effects (aesthetic, social, political etc) do you think the artist was trying to achieve in this work? 2. Has the film helped you define some of the formal elements of the work? Consider scale, subject matter, medium, and other formal elements 3. Does it have a recognisable purpose or function? Does this relate to the time period in which it was made? 4. -

Whitechapel Gallery Publications

For over a century the Trade orders New and recent ”La Caixa” Collection at Previous titles in the series: Whitechapel Gallery has exhibition titles Whitechapel Gallery Thames & Hudson A series of four special publications premiered world-class 181a High Holborn to accompany a year-long display of artists such as Jackson London, WC1V 7QX works from Barcelona’s ”La Caixa” Pollock, Frida Kahlo and +44 (0) 20 7845 5000 Collection at Whitechapel Gallery [email protected] in four chapters, selected by and David Hockney, as well featuring newly-commissioned as groundbreaking group Selected exhibition titles available NEW fictional works by some of the most exhibitions. We continue in North America through: Max Mara Art Prize for Women 2019: distinctive English and Spanish- Artbook | D.A.P. language writers working today. Cabinet d’amateur, an oblique novel to showcase the best in NEW Helen Cammock 75 Broad Street, Suite 630 Anna Maria Maiolino Edited by Laura Smith, Bilingual edition (English/Spanish) by Enrique Vila-Matas contemporary art, alongside New York, NY 10004 Making Love Revolutionary with Candy Stobbs Paperback, 96pp 978-0-85488-273-1 our pioneering education and +1 (212) 627 1999 Edited by Lydia Yee, 210 x 148mm Whitechapel Gallery [email protected] Bilingual edition (English/Italian) public events programmes. with Trinidad Fombella Paperback with 7-inch vinyl, 152pp £14.99 Paperback 280 × 215 mm 978-0-85488-279-3 978-0-85488-277-9 Publications September 2019 June 2019 £24.99 £19.99 (inc VAT) Cover: Yinka Shonibare, Anna Maria Maiolino’s (b. 1942, The seventh winner of the biennial The British Library, 2014 (detail) Calabria; lives and works in São Paulo) Max Mara Art Prize for Women, Helen © Yinka Shonibare CBE. -

A Brief History of the Arts Catalyst

A Brief History of The Arts Catalyst 1 Introduction This small publication marks the 20th anniversary year of The Arts Catalyst. It celebrates some of the 120 artists’ projects that we have commissioned over those two decades. Based in London, The Arts Catalyst is one of Our new commissions, exhibitions the UK’s most distinctive arts organisations, and events in 2013 attracted over distinguished by ambitious artists’ projects that engage with the ideas and impact of science. We 57,000 UK visitors. are acknowledged internationally as a pioneer in this field and a leader in experimental art, known In 2013 our previous commissions for our curatorial flair, scale of ambition, and were internationally presented to a critical acuity. For most of our 20 years, the reach of around 30,000 people. programme has been curated and produced by the (founding) director with curator Rob La Frenais, We have facilitated projects and producer Gillean Dickie, and The Arts Catalyst staff presented our commissions in 27 team and associates. countries and all continents, including at major art events such as Our primary focus is new artists’ commissions, Venice Biennale and dOCUMEntA. presented as exhibitions, events and participatory projects, that are accessible, stimulating and artistically relevant. We aim to produce provocative, Our projects receive widespread playful, risk-taking projects that spark dynamic national and international media conversations about our changing world. This is coverage, reaching millions of people. underpinned by research and dialogue between In the last year we had features in The artists and world-class scientists and researchers. Guardian, The Times, Financial Times, Time Out, Wall Street Journal, Wired, The Arts Catalyst has a deep commitment to artists New Scientist, Art Monthly, Blueprint, and artistic process. -

Yinka Shonibare MBE: FABRIC-ATION

COPENHAGEN, JULY 3RD 2013 PRESS RELEASE Yinka Shonibare MBE: FABRIC-ATION 21. september – 24. november 2013 Autumn at GL STRAND offers one of the absolutely major names on the international contemporary art scene. British-Nigerian Yinka Shonibare is currently arousing the enthusiasm of the public and reviewers in England. Now the Danish public will have a chance to make the acquaintance of the artist’s fascinating universe of headless soldiers and Victorian ballerinas in his first major solo show in Scandinavia. Over the part 15 years Yinka Shonibare has created an iconic oeuvre of headless mannequins that bring to life famous moments of history and art history. With great commitment and equal degrees of seriousness, wit and humour he has mounted an assault on the colonialism of the Victorian era and its parallels in Thatcher’s Britain. In recent years he has widened the scope of his subjects to include global news, injustices and complications in a true cornucopia of media, for example film, photography, painting, sculpture and installation – all represented in the show at GL STRAND. FABRIC-ATION mainly gathers works from recent years, as well as a brand new work created for the exhibition, Copenhagen Girl with a Bullet in her Head. The subjects include Admiral Nelson and his key position in British colonialism, the significance of globalization for the formation of modern man’s identity, multiculturalism, global food production and the revolutions of the past few years in the Arab world. In other words, Shonibare is able, through an original and captivating universe, to present us with the huge complexity that defines our time, as well as the underlying history. -

What's on at Gainsborough's House

Visitor information What’s on at Gainsborough’s House NOVEMBER 2018 – MAY 2019 OPEN Monday to Saturday 10am–5pm GIRLING STREET Sunday 11am–5pm AST STREET E CLOSED Good Friday and between GREGOR Christmas and the New Year Y ST * WEAVERS ADMISSION (with Gift Aid ) HILLGAINSBOROUGH’S STATUE Adults: £7 DESIGN: TREVOR WILSON DESIGN GAINSBOROUGH’S LANE MARKETKING ST Family: £16 HOUSE CORNARD ROAD Children aged up to 5: free ST BUS Children and students: £2 GAINSBOROUGH STATION STOUR ST STATION ROAD Groups of 10 or more: RIARS ST F £6 per head (booking essential) SUDBURY All admissions, courses and lectures are STATION inclusive of VAT (VAT No. 466111268). Gainsborough’s House is an accredited museum. Charity No. 1170048 and Company Limited by Guarantee No. 10413978. It is supported by Suffolk County Council, Sudbury Town Council, Friends & Patrons of Gainsborough’s House. Gainsborough’s House 46 Gainsborough Street, Sudbury, Suffolk CO10 2EU (entrance in Weavers Lane) Telephone 01787 372958 [email protected] www.gainsborough.org Twitter @GH_Sudbury The House and Garden have wheelchair access and there is a lift to the first floor. * The additional income from Gift Aid does make a big difference but if you prefer not to make this contribution the admission prices are: Adult £6.30, Family £14.50. 1 Gainsborough’s House Gainsborough in Sudbury THOMAS GAINSBOROUGH FRONT COVER: Thomas Gainsborough (1727–88) was born THE ROOMS OF MR & MRS JOHN BROWN AND THEIR in Sudbury and was baptised there at the GAINSBOROUGH’S HOUSE ‘The name of Gainsborough will be transmitted DAUGHTER, ANNA MARIA, Independent Meeting-House in Friars Street to posterity, in the history of art.’ Each of the rooms of the house take a c.