Refugee Resettlement in the Andaman Islands

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Freedom in West Bengal Revised

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by ResearchArchive at Victoria University of Wellington Freedom and its Enemies: Politics of Transition in West Bengal, 1947-1949 * Sekhar Bandyopadhyay Victoria University of Wellington I The fiftieth anniversary of Indian independence became an occasion for the publication of a huge body of literature on post-colonial India. Understandably, the discussion of 1947 in this literature is largely focussed on Partition—its memories and its long-term effects on the nation. 1 Earlier studies on Partition looked at the ‘event’ as a part of the grand narrative of the formation of two nation-states in the subcontinent; but in recent times the historians’ gaze has shifted to what Gyanendra Pandey has described as ‘a history of the lives and experiences of the people who lived through that time’. 2 So far as Bengal is concerned, such experiences have been analysed in two subsets, i.e., the experience of the borderland, and the experience of the refugees. As the surgical knife of Sir Cyril Ratcliffe was hastily and erratically drawn across Bengal, it created an international boundary that was seriously flawed and which brutally disrupted the life and livelihood of hundreds of thousands of Bengalis, many of whom suddenly found themselves living in what they conceived of as ‘enemy’ territory. Even those who ended up on the ‘right’ side of the border, like the Hindus in Murshidabad and Nadia, were apprehensive that they might be sacrificed and exchanged for the Hindus in Khulna who were caught up on the wrong side and vehemently demanded to cross over. -

Development Or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar

Andaman Islands: Development or Despoilation? - Krishnakumar DEVELOPMENT OR DESPOILATION? The Andaman Islands under colonial and postcolonial regimes M.V. KRISHNAKUMAR Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi <[email protected]> Abstract The last quarter of the 19th Century marked an important watershed in the history of the Andaman Islands. The establishment of a penal settlement and an Imperial forestry service, along with other radical changes in the islands’ traditional economy and society, completely transformed the basic pattern of their forest resource use and entire system of forest management. These colonial policies, directly or indirectly, had a drastic impact on the indigenous population and island ecology. This article analyses the sources of environmental change in the Andaman Islands by examining the general ecological impacts of the state initiated development programmes. It also analyses the ‘civilising missions’ and forestry operations undertaken by British colonial administrators as well as the Indian state’s development initiatives under the ‘Five Year Plans’ that followed Indian independence in 1947. Keywords Andaman Islands, forestry, development, environmental change, Andaman tribes Introduction On December 26th 2004 a tsunami triggered by an earthquake off the south east coast of Sumatra swept across the Indian Ocean swamping many low-lying coastal areas and causing death, destruction of properties and infrastructure and despoliation of crops. Amongst those territories worst affected by the surge were the Andaman and Nicobar Islands. When Indian prime minister Dr Manmohan Singh visited the islands in the immediate aftermath of the flooding he identified that the project to reconstruct and rehabilitate coastal areas of islands provided the opportunity for a ‘New Andamans’ in which sustainable agriculture and fishery enterprises could exist in harmony with the natural environment. -

The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire*

IRSH 63 (2018), Special Issue, pp. 25–43 doi:10.1017/S0020859018000202 © 2018 Internationaal Instituut voor Sociale Geschiedenis. This is an Open Access article, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution licence (http:// creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The Andaman Islands Penal Colony: Race, Class, Criminality, and the British Empire* C LARE A NDERSON School of History, Politics and International Relations University of Leicester University Road, Leicester LE1 7RH, UK E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT: This article explores the British Empire’s configuration of imprisonment and transportation in the Andaman Islands penal colony. It shows that British governance in the Islands produced new modes of carcerality and coerced migration in which the relocation of convicts, prisoners, and criminal tribes underpinned imperial attempts at political dominance and economic development. The article focuses on the penal transportation of Eurasian convicts, the employment of free Eurasians and Anglo-Indians as convict overseers and administrators, the migration of “volunteer” Indian prisoners from the mainland, the free settlement of Anglo-Indians, and the forced resettlement of the Bhantu “criminal tribe”.It examines the issue from the periphery of British India, thus showing that class, race, and criminality combined to produce penal and social outcomes that were different from those of the imperial mainland. These were related to ideologies of imperial governmentality, including social discipline and penal practice, and the exigencies of political economy. INTRODUCTION Between 1858 and 1939, the British government of India transported around 83,000 Indian and Burmese convicts to the penal colony of the Andamans, an island archipelago situated in the Bay of Bengal (Figure 1). -

Arachnozoogeographical Analysis of the Boundary Between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region

Historia naturalis bulgarica, 23: 5-36, 2016 Arachnozoogeographical analysis of the boundary between Eastern Palearctic and Indomalayan Region Petar Beron Abstract: This study aims to test how the distribution of various orders of Arachnida follows the classical subdivision of Asia and where the transitional zone between the Eastern Palearctic (Holarctic Kingdom) and the Indomalayan Region (Paleotropic) is situated. This boundary includes Thar Desert, Karakorum, Himalaya, a band in Central China, the line north of Taiwan and the Ryukyu Islands. The conclusion is that most families of Arachnida (90), excluding most of the representatives of Acari, are common for the Palearctic and Indomalayan Regions. There are no endemic orders or suborders in any of them. Regarding Arach- nida, their distribution does not justify the sharp difference between the two Kingdoms (Paleotropical and Holarctic) in Eastern Eurasia. The transitional zone (Sino-Japanese Realm) of Holt et al. (2013) also does not satisfy the criteria for outlining an area on the same footing as the Palearctic and Indomalayan Realms. Key words: Palearctic, Indomalayan, Arachnozoogeography, Arachnida According to the classical subdivision the region’s high mountains and plateaus. In southern Indomalayan Region is formed from the regions in Asia the boundary of the Palearctic is largely alti- Asia that are south of the Himalaya, and a zone in tudinal. The foothills of the Himalaya with average China. North of this “line” is the Palearctic (consist- altitude between about 2000 – 2500 m a.s.l. form the ing og different subregions). This “line” (transitional boundary between the Palearctic and Indomalaya zone) is separating two kingdoms, therefore the dif- Ecoregions. -

Bibliography

Bibliography 337 Bibliography A.Primary Sources 1. Committee of Ministers‟ Report. 2. WBLA, Vol. XVII, No.2, 1957. 3. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on the Medical Facilities for New Migrants from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal. 4. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on the Education Facilities for New Migrants from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal. 5. WBLA, Vol. XIV, No. 1, 1956. 6. Committee of Review of Rehabilitation Report on Rehabilitation of Displaced Persons from Erstwhile East Pakistan in West Bengal, Third Report. 7. Working Group Report on the Residual problem of Rehabilitation. 8. S. K. Gupta Papers, File Doc. DS: „DDA- Official Documents‟, NMML. 9. 6th Parliament Estimate Committee 30th Report. 10. Indian Parliament, Estimates Committee Report, 30th Report. Dandakaranya Project: Exodus of Settlers, New Delhi, 1979. 11. Estimate Committee, 1959-60, Ninety-Sixth Report, Second Loksabha. 12. WBLA, Vol. XV, No.2, 1957 13. Ninety-Sixth Report of the Estimates Committee, 1959-60, (Second Loksabha) 14. UCRC Executive Committee‟s Report, 16th Convention. 15. Govt. of West Bengal, Master Plan. 16. SP Mukherjee Papers, NMML. 17. Council Debates (Official report), West Bengal Legislative Council, First Session, June – August 1952, vol. I. Census Report 1. Census Report of 1951, Government of West Bengal, India. 2. Census of India 1961, Vol. XVI, part I-A, book (i), p.175. 3. Census Report, 1971. 4. Census of India, 2001. 338 Official and semi-official publications 1. Dr. Guha, B. S., Memoir No. 1, 1954. Studies in Social Tensions among the Refugees from Eastern Pakistan, Department of Anthropology, Government of India, Calcutta, 1959. -

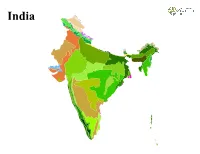

R Graphics Output

India India LEGEND Ecoregion Andaman Islands rain forests Mizoram−Manipur−Kachin rain forests Aravalli west thorn scrub forests Narmada Valley dry deciduous forests Baluchistan xeric woodlands Nicobar Islands rain forests Brahmaputra Valley semi−evergreen forests North Deccan dry deciduous forests Central Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests North Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Central Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe North Western Ghats montane rain forests Chhota−Nagpur dry deciduous forests Northeast Himalayan subalpine conifer forests Chin Hills−Arakan Yoma montane forests Northeast India−Myanmar pine forests Deccan thorn scrub forests Northern Triangle temperate forests East Deccan dry−evergreen forests Northwestern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows East Deccan moist deciduous forests Orissa semi−evergreen forests Eastern Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Rann of Kutch seasonal salt marsh Eastern Himalayan broadleaf forests Rock and Ice Eastern Himalayan subalpine conifer forests South Deccan Plateau dry deciduous forests Godavari−Krishna mangroves South Western Ghats moist deciduous forests Himalayan subtropical broadleaf forests South Western Ghats montane rain forests Himalayan subtropical pine forests Sundarbans freshwater swamp forests Indus River Delta−Arabian Sea mangroves Sundarbans mangroves Karakoram−West Tibetan Plateau alpine steppe Terai−Duar savanna and grasslands Khathiar−Gir dry deciduous forests Thar desert Lower Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Upper Gangetic Plains moist deciduous forests Malabar Coast moist forests Western Himalayan alpine shrub and meadows Maldives−Lakshadweep−Chagos Archipelago tropical moist forests Western Himalayan broadleaf forests Meghalaya subtropical forests Western Himalayan subalpine conifer forests. -

Resume of DR. JYOTI PROSAD ROY

Resume of DR. JYOTI PROSAD ROY Dr. JYOTI PROSAD ROY Professor, Department of Bengali Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University,Vivekananda Street, Cooch Behar-736101, West Bengal, Contact No : +91-8944819046 Email : [email protected] Name Sri Jyoti Prosad Roy Personal Name : Sri Jyoti Prosad Roy Information Father’s Name : Late Bimal Roy Mother’s Name : Smt. Niharika Roy Present Address : Professor, Department of Bengali, Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University, Cooch Behar-736101. Permanent Address : B.G. Apartment, 5th Floor, Flat-A, P.O+Distric:Cooch Behar, Pin- 736101,West Bengal, India. Date of Birth : October 17, 1971 Religion : Hindu Blood Group : O+ Nationality : Indian (By Birth) Marital Status : Married Designation Professor Department Department of Bengali, Cooch Behar Panchanan Barma University Faculty Arts And Humanity Academic M.A. (Calcutta University), Qualification B.Ed (Calcutta University), NET(UGC), Ph. D. (Burdwan University) D. Lit. (Ranchi University, Yet to final submission) Teaching Area The theme and crafts of Modern Bengali Literature, especially in (field of 20th Century. specialization) Research Modern Bengali Fiction & Non-fiction, Literary Theory and Literary movement in Area: modern Bengali literature, 20th Century War Literature, Relation between Nature, Art and Culture in Literature etc. 1 Books List of publications: I. Baren Basu’r Samar Natak : ‘Chhauni’ (20th Century War Drama of Soldier-writer Baren Basu, A Research Book), Rritabak Publication, Kolkata, 2020. ISBN : 978-81-944223-4-1 II. Kamal (Kumar) Mazumdar O Bilupta ‘Ushnish’ Patrika (Kamal Kumar Mazumdar : Discover his early stage unknown writings and outlook as an Editor, A research Book), Dargaroad Publication, Kolkata, 2017. ISBN :978-93-5126-860-4 III. -

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders

Two Nation Theory: Its Importance and Perspectives by Muslims Leaders Nation The word “NATION” is derived from Latin route “NATUS” of “NATIO” which means “Birth” of “Born”. Therefore, Nation implies homogeneous population of the people who are organized and blood-related. Today the word NATION is used in a wider sense. A Nation is a body of people who see part at least of their identity in terms of a single communal identity with some considerable historical continuity of union, with major elements of common culture, and with a sense of geographical location at least for a good part of those who make up the nation. We can define nation as a people who have some common attributes of race, language, religion or culture and united and organized by the state and by common sentiments and aspiration. A nation becomes so only when it has a spirit or feeling of nationality. A nation is a culturally homogeneous social group, and a politically free unit of the people, fully conscious of its psychic life and expression in a tenacious way. Nationality Mazzini said: “Every people has its special mission and that mission constitutes its nationality”. Nation and Nationality differ in their meaning although they were used interchangeably. A nation is a people having a sense of oneness among them and who are politically independent. In the case of nationality it implies a psychological feeling of unity among a people, but also sense of oneness among them. The sense of unity might be an account, of the people having common history and culture. -

Indian Institute of Technology

INDIAN INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY Kharagpur 721302, West Bengal Tel : 03222-282002, 255386, 277201, 282022, 255622, 282023 Fax : 03222-282020, 255303 Email : [email protected], [email protected] Website : http://www.iitkgp.ernet.in The Indian Institute of Technology Kharagpur (IIT Kharagpur or IIT KGP) is a public engineering institution established by the government of India in 1951. The first of the IITs to be established, it is recognized as an Institute of National Importance by the government of India. The institute was established to train scientists and engineers after India attained independence in 1947. It shares its organisational structure and undergraduate admission process with sister IITs. The students and alumni of IIT Kharagpur are informally referred to as KGPians. Among all IITs, IIT Kharagpur has the largest campus (2,100 acres), the most departments, and the highest student enrolment. IIT Kharagpur is known for its festivals: Spring Fest (Social and Cultural Festival) and Kshitij (Techno-Management Festival). With the help of Bidhan Chandra Roy (chief minister of West Bengal), Indian educationalists Humayun Kabir and Jogendra Singh formed a committee in 1946 to consider the creation of higher technical institutions "for post-war industrial development of India." [ This was followed by the creation of a 22-member committee headed by Nalini Ranjan Sarkar. In its interim report, the Sarkar Committee recommended the establishment of higher technical institutions in India, along the lines of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and consulting from the University of Illinois at Urbana–Champaign along with affiliated secondary institutions. The report urged that work should start with the speedy establishment of major institutions in the four-quarters of the country with the ones in the east and the west to be set up immediately. -

Islands, Coral Reefs, Mangroves & Wetlands In

Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan 2007-2012 Government of India PLANNING COMMISSION New Delhi (March, 2007) Report of the Task Force on ISLANDS, CORAL REEFS, MANGROVES & WETLANDS IN ENVIRONMENT & FORESTS For the Eleventh Five Year Plan (2007-2012) CONTENTS Constitution order for Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves and Wetlands 1-6 Chapter 1: Islands 5-24 1.1 Andaman & Nicobar Islands 5-17 1.2 Lakshwadeep Islands 18-24 Chapter 2: Coral reefs 25-50 Chapter 3: Mangroves 51-73 Chapter 4: Wetlands 73-87 Chapter 5: Recommendations 86-93 Chapter 6: References 92-103 M-13033/1/2006-E&F Planning Commission (Environment & Forests Unit) Yojana Bhavan, Sansad Marg, New Delhi, Dated 21st August, 2006 Subject: Constitution of the Task Force on Islands, Corals, Mangroves & Wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan (2007- 2012). It has been decided to set up a Task Force on Islands, corals, mangroves & wetlands for the Environment & Forests Sector for the Eleventh Five-Year Plan. The composition of the Task Force will be as under: 1. Shri J.R.B.Alfred, Director, ZSI Chairman 2. Shri Pankaj Shekhsaria, Kalpavriksh, Pune Member 3. Mr. Harry Andrews, Madras Crocodile Bank Trust , Tamil Nadu Member 4. Dr. V. Selvam, Programme Director, MSSRF, Chennai Member Terms of Reference of the Task Force will be as follows: • Review the current laws, policies, procedures and practices related to conservation and sustainable use of island, coral, mangrove and wetland ecosystems and recommend correctives. -

North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002

Reconnaissance Report North Andaman (Diglipur) Earthquake of 14 September 2002 ATR Smith Island Ross Island Aerial Bay Jetty Diglipur Shibpur ATR Kalipur Keralapuran Kishorinagar Saddle Peak Nabagram Kalighat North Andaman Ramnagar Island Stewart ATR Island Sound Island Mayabunder Jetty Middle Austin Creek ATR Andaman Island Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 Field Study Sponsored by: Department of Science and Technology, Government of India, New Delhi Printing of Report Supported by: United Nations Development Programme, New Delhi, India Dissemination of Report by: National Information Center of Earthquake Engineering, IIT Kanpur, India Copies of the report may be requested from: National Information Center for Earthquake Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208016 www.nicee.org Email: [email protected] Fax: (0512) 259 7866 Cover design by: Jnananjan Panda R ECONNAISSANCE R EPORT NORTH ANDAMAN (DIGLIPUR) EARTHQUAKE OF 14 SEPTEMBER 2002 by Durgesh C. Rai C. V. R. Murty Department of Civil Engineering Indian Institute of Technology Kanpur Kanpur 208 016 Sponsored by Department of Science & Technology Government of India, New Delhi April 2003 ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS We are sincerely thankful to all individuals who assisted our reconnaissance survey tour and provided relevant information. It is rather difficult to name all, but a few notables are: Dr. R. Padmanabhan and Mr. V. Kandavelu of Andaman and Nicobar Administration; Mr. Narendra Kumar, Mr. S. Sundaramurthy, Mr. Bhagat Singh, Mr. D. Balaji, Mr. K. S. Subbaian, Mr. M. S. Ramamurthy, Mr. Jina Prakash, Mr. Sandeep Prasad and Mr. A. Anthony of Andaman Public Works Department; Mr. P. Radhakrishnan and Mr. -

01720Joya Chatterji the Spoil

This page intentionally left blank The Spoils of Partition The partition of India in 1947 was a seminal event of the twentieth century. Much has been written about the Punjab and the creation of West Pakistan; by contrast, little is known about the partition of Bengal. This remarkable book by an acknowledged expert on the subject assesses partition’s huge social, economic and political consequences. Using previously unexplored sources, the book shows how and why the borders were redrawn, as well as how the creation of new nation states led to unprecedented upheavals, massive shifts in population and wholly unexpected transformations of the political landscape in both Bengal and India. The book also reveals how the spoils of partition, which the Congress in Bengal had expected from the new boundaries, were squan- dered over the twenty years which followed. This is an original and challenging work with findings that change our understanding of parti- tion and its consequences for the history of the sub-continent. JOYA CHATTERJI, until recently Reader in International History at the London School of Economics, is Lecturer in the History of Modern South Asia at Cambridge, Fellow of Trinity College, and Visiting Fellow at the LSE. She is the author of Bengal Divided: Hindu Communalism and Partition (1994). Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society 15 Editorial board C. A. BAYLY Vere Harmsworth Professor of Imperial and Naval History, University of Cambridge, and Fellow of St Catharine’s College RAJNARAYAN CHANDAVARKAR Late Director of the Centre of South Asian Studies, Reader in the History and Politics of South Asia, and Fellow of Trinity College GORDON JOHNSON President of Wolfson College, and Director, Centre of South Asian Studies, University of Cambridge Cambridge Studies in Indian History and Society publishes monographs on the history and anthropology of modern India.