Extract from a Conservation Statement for the Former Chapel, Tolpuddle for the Tolpuddle Old Chapel Trust Contents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dorset History Centre

GB 0031 D40E Dorset History Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 12726 The National Archives DORSET RECORD OFFICE H. M. C. 12726 D40E Deposited by Thos. ooornbs £ Son, Solicitors^ NATIONA L REGISTER 15th May, 1967. OF ARCHIVES (See also NRA 16221 WESLEY FAMILY PAPERS, Dorset R.O. D40 G) pfr u Bundle No. Date Description of Documents No. of nocumenti DORSET"" 1. 1798 "Report on the Coast of Dorsetshire, 1793" by Wm. Morton 1 vol. Pitt, for purpose of planning defence. Largely on pos sible landing places, present armament; suggestions as to stationing guns and troops. At back: table showing guns serviceable, unserviceable and wanting. At front: map of Dorset reduced from Isaac Taylor's 1" map and published by \i, Faden in 1796. 2. 1811 Dorset 1st ed. 1" O.S. map showing coast from Charmouth 1 to Bindon Hill. - 3. 1811 Dorset 1st ed. 1" O.S. map, sheet XV, showing Wimborne 1 and Cranborne area and part of Hampshire. BUCKLAID NEWTON 4. 1840 Copy tithe map. 1 CHARMINSTER ND 5. Extract from tithe map, used in case Lord Ilchester v. 1 Henning. DCRCHESTER 6. (Post 1834) Map , undated. (Goes with survey in Dorchester 3orough 1 records which is dated 1835 or after). Shows properties of Corporation, charities, schools. 7. - 1848 Map, surveyed 1810, corrected 1848 by F.C. Withers. 4 Indicates lands belonging to Earl of Shaftesbury, Robert Williams, the Corporation; shows parish boundaries.(2 copies). Survey showing proprietors, occupiers, descri ption of premises, remarks. -

THE FREE WESSEX ARTS and CULTURE GUIDE EVOLVER May and June 2019 EVOLVER 111:Layout 1 23/04/2019 18:50 Page 2

EVOLVER_111:Layout 1 23/04/2019 18:49 Page 1 THE FREE WESSEX ARTS AND CULTURE GUIDE EVOLVER May and June 2019 EVOLVER_111:Layout 1 23/04/2019 18:50 Page 2 2 EVOLVER_111:Layout 1 23/04/2019 18:50 Page 3 EVOLVER 111 EXHIBIT A ZARA MCQUEEN: ‘AS THE CROW FLIES’ Mixed media (120 x 150 cm) ARTIST’S STATEMENT: “Drawing and painting is part of who I am. It is how I respond to my world. I am driven by mood and intuition. I always begin outside. In that sense I am a landscape painter. Seasonal changes catch my attention and I can rarely resist the changing colours and textures of the natural year. I sketch and paint in watercolour, charcoal or oil then return to the studio where I make larger mixed media pieces guided by memory and feeling. Work gets cut down, torn up, collaged and reformed. Fragments of self portraits often lay hidden in fields, branches or buildings.” ‘DRAWN IN’ 11 May - 15 June: Bridport Arts Centre, South Street, BRIDPORT, DT6 3NR. Tuesday - Saturday 10am - 4pm. 01308 424204 / bridport-arts.com. zara-mcqueen.co.uk EVOLVER Email [email protected] THE WESSEX ARTS AND CULTURE GUIDE Telephone 01935 808441 Editor SIMON BARBER Website evolver.org.uk Assisted by SUZY RUSHBROOK Instagram evolvermagazine Evolver Writer Twitter @SimonEvolver FIONA ROBINSON www.fionarobinson.com Facebook facebook.com/EvolverMagazine Graphic Design SIMON BARBER Published by EVOLVER MEDIA LIMITED Website OLIVER CONINGHAM at AZTEC MEDIA Pre-Press by FLAYDEMOUSE Front Cover 01935 479453 / flaydemouse.com JEREMY GARDINER: ‘WEST BAY IV’ Printed by STEPHENS & GEORGE (Painting) Distributed by ACOUSTIC See page 4. -

Vebraalto.Com

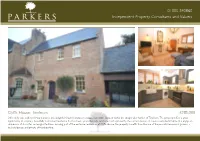

01305 340860 Independent Property Consultants and Valuers Clyffe House, Tincleton £285,000 Offered for sale with no forward chain is this delightful Grade II character cottage, favourably situated within the sought after hamlet of Tincleton. The property offers a great opportunity to acquire a beautifully maintained residence that has been sympathetically renovated and updated by the current owners to create a wonderful home that enjoys an abundance of character and original features. Forming part of the exclusive conversion of Clyffe House, the property benefits from the use of the peaceful communal gardens, a freehold garage and private off road parking. 7 The Courtyard Clyffe House, Tincleton, Dorset, DT2 8QR Situation Situated approximately five miles from the county town of Dorchester, Tincleton is a peaceful and idyllic Dorset village with all the advantages of proximity to major towns with excellent shopping and dining facilities and rail services to London Waterloo (approximately 2.5 hours from Dorchester). Nearby Dorchester is steeped in history enjoying a central position along the Jurassic Coastline and also some of the county's most noted period architecture, all set amongst a beautiful rural countryside. Dorchester offers a plethora of shopping and social facilities. Two cinemas, several museums, History centre, leisure centre, weekly market, many excellent restaurants and public houses and riverside walks. The catchment schools are highly rated and very popular with those in and around the Dorchester area. Doctors, dentist surgeries and the Dorset County Hospital are close by. There are major train links to London Waterloo, Bristol Temple Meads and Weymouth and other coastal towns and villages, and regular bus routes to nearby towns. -

5396 the LONDON GAZETTE, 25Ra APRIL 1975

5396 THE LONDON GAZETTE, 25ra APRIL 1975 The County Council of Dorset (Roads Restriction) amended by Part IX of the Transport Act, 1968, Schedule (No. 1) Order 1953. 19 to the Local Government Act, 1972, and Schedule 6 . The County Council of Dorset (Roads Restriction) to the Road Traffic Act, 1974. (Amendment) (No. 1) Order 1959. When this Order comes into effect on 28th April 1975, The County Council of Dorset (Roads Restriction) no person shall cause any motor vehicle, the unladen (Amendment) (No. 2) Order 1959. weight of which exceeds 3 tons, to proceed in any of the The County of Dorset (Railway Bridge, Blacknoll Lane, lengths of road specified hereunder. Winfrith Newburgh) (Weight Restriction) Order 1960. Lengths of Road in West Dorset District The County Council of Dorset Roads (Restriction) Order 1936 (Amendment) Order 1962. 1. The road to Stinsford Church from its junction with The County Council of Dorset (Roads Restriction) the Dorchester-Tinctleton road to its termination at St. (No. 1) Order 1952 (Amendment) Order 1962. Michael's Church. 2. Cuckoo Lane and Bockhampton Lane from its junction A copy of the Order and a plan showing the roads with the Dorchester-Puddletown Road (A.35) to its junc- affected are available for inspection during normal office tion with the Dorchester-West Stafford road 300 yards west hours Monday to Friday at: of Stafford House. (i) Dorset County Council, Transportation! and Engineer- 3. Cobb Road from its junction with Pound Street ing Department, County Hall, Dorchester. (A.3052) to its termination at the Cobb Harbour, a distance (ii) West Dorset District Council, 58 High West Street, of approximately 0-3 mile. -

Dorset History Centre

GB 0031 D.1383 Dorset History Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 40810 The National Archives D.1383 DORSET GUIDE ASSOCIATION 1 MID DORSET DIVISION 1/1 Minute Book (1 vol) 1971-1990 2 1ST CERNE ABBA S GUIDE COMPAN Y 2/1 Company Register (lvol) ' 1953-1965 3 1ST OWERMOIGN E BROWNIE PACK 3/1 Pack Register (1 vol) 1959-1962 3/2 Account Book (1 vol) 1959-1966 4 1ST OWERMOIGN E GUIDE COMPAN Y 4/1 Account Book (1 vol) 1959-1966 D.1383 DORSET GUIDE ASSOCIATION 5 SWANAGE AND DISTRICT GIRL GUIDES A5 HANDBOOKS A5/1 Girl Guiding: The Official Handbook by Sir Robert Baden-Powell, detailing the aims and methods of the organisation, including fly-leaf note ' G A E Potter, Dunraven, 38 Parkstone Road, Poole, Dorset' (1 vol) 1920 B5 MINUTES B5/1 Minute book for Lone Girl Guides, Dorset with pasted in annual reports 1965-1968 and a newspaper cutting (1 vol) 1964-1970 B5/2 Articles on the East Dorset divisional meeting by Miss C C Mount-Batten, notices and appointments (3 docs) 1925 C5 MEMBERS C5/1 Packs C5/1/1 Photograph of a brownie pack (1 doc) n.d.[ 1920s] C5/1/2 Photograph of five members of a girl guide company (ldoc) n.d.[1920s] C5/1/3 Photograph of a girl guide company on a trip (ldoc) n.d.[1920s] C5/1/4 Group photograph of 7th Parkstone company and pack and ranger patrol with a key to names (2 docs) 1928 D.1383 DORSE T GUD3E ASSOCIATIO N C5 MEMBER S C5/2 Individuals C5/2/1 Girl guide diaries, written by the same person (?), with entries for each day, -

Minutes of Puddletown Area Parish Council Meeting Held on Thursday 15Th April, 2010 at Tolpuddle Village Hall, Commencing 7.30P.M

Minutes of Puddletown Area Parish Council meeting held on Thursday 15th April, 2010 at Tolpuddle Village Hall, commencing 7.30p.m. Present: M Oddy, B Legg, J Hopkin, M Crankshaw, A Sheppard, C Leonard, T White, P Drake Chair: S Buck Clerk: Mrs A Crocker 3 members of the public. PCSO Vicky Hedge The Chairman asked those members of the public present if they would like to make any comments or ask any questions. Mr Tony Gould reported that, in the Village Meeting, they had been talking about the old chapel building where the Martyrs met for worship. It is described as a building of great historic interest and there is talk that the villagers would like to get it restored and it would add to the historical content and heritage of the village. It was built in 1818 but fell into disuse in about 1840 and was replaced by the new chapel in 1862/63. It was originally on a life hold tenancy reverting back to the land owner once the tenant died. It is a project the village would like to take up. This is a grade II* listed building. It was suggested that the way forward would be to involve the owner of the site. The Parish Council would be happy to back any project involving the renovation of the building. M Cooke has already provided them with some contact names and numbers. Bob Dean – adoption of road on Central farm estate. The Clerk will contact the appropriate authority to find out what is happening. It is understood that a financial bond would have been set up to cover this sort of eventuality. -

![Dewlish. (Dorset.]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7175/dewlish-dorset-787175.webp)

Dewlish. (Dorset.]

DIR~CTORY• 3l DEWLISH. (DORSET.] Rixen William1 furmer Still William, cooper & lathrender Wareham William, shopkeeper San8om Willi!Hil, farmer, A~hes Thoma~ J osi11.h, carpenter & wheelwrght Waters William,farmer Simmonds James, fdrmer, Oakey Tink Robert, farmer, Monckton-up- Witt Amhrose, farmer, Verwood Stanford James, steward to the Marquis 'Vimhorne YoungJohn, blacksmith of Salisbury, Manor house Ware Jane (Mrs.), i!'onmonger & smith PosT 0FFICB.-MiEs M11.ry Ann Harveyl postmistress., arrive per mail cart from Salisbury at 7 a.m.; dispatched Money orders are granted & paid at this office. Letters at 25 m in, after 6 p.m. Box closes at ~ past 5 St. Bartholomew's Church, Rev. John H. Carne~ie, \'icar tuesday & saturday; James Gray, from Wimborne, call8 Relieving Officer~ Reg'istrar of Birth$~ Deaths (Gran- at the ' Sheaf of Arrows,' every ntonday morning at 12, borne District), John Hunt returns tuesday afternoon at 4 CARRIERS TO & FROM SALISBURY-Robert Bound, every DEWLlSH is ll. remote \'illage, lying in a hollow, and Andrew's, and enjoyed by the Rev. Thomas Blare, who bounded on the east by an extensive plantation j it is a officiates here and at Milborne 8t. Andrew's alternately, parish and Liherty, in Oorchester Union and di\"ision, morning- and afternoon. There i~ a chapel for Wesleyans; situated 8 mile9 north-east of Dorchester, 6 north-We9t also a Parochial school. The Old Manor House (so called from Beer Regis, 10 south-west from Blandford; the from its having been formerly the residence of the lord of population, in 1851, was 442, with 2,090 acres. -

Final Copy 2020 02 17 Baker

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Baker, Leonard Title: Spaces, Places, Custom and Protest in Rural Somerset and Dorset, c. 1780-1867. General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. Spaces, Places, Custom and Protest in Rural Somerset and Dorset, c. 1780-1867 Leonard John Baker A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for award of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts School of Humanities September 2019 Word Count: 79,998 Abstract This thesis examines how material space, meaningful place and custom shaped the forms and functions of protest in rural Somerset and Dorset between 1780 and 1867. -

International Passenger Survey, 2008

UK Data Archive Study Number 5993 - International Passenger Survey, 2008 Airline code Airline name Code 2L 2L Helvetic Airways 26099 2M 2M Moldavian Airlines (Dump 31999 2R 2R Star Airlines (Dump) 07099 2T 2T Canada 3000 Airln (Dump) 80099 3D 3D Denim Air (Dump) 11099 3M 3M Gulf Stream Interntnal (Dump) 81099 3W 3W Euro Manx 01699 4L 4L Air Astana 31599 4P 4P Polonia 30699 4R 4R Hamburg International 08099 4U 4U German Wings 08011 5A 5A Air Atlanta 01099 5D 5D Vbird 11099 5E 5E Base Airlines (Dump) 11099 5G 5G Skyservice Airlines 80099 5P 5P SkyEurope Airlines Hungary 30599 5Q 5Q EuroCeltic Airways 01099 5R 5R Karthago Airlines 35499 5W 5W Astraeus 01062 6B 6B Britannia Airways 20099 6H 6H Israir (Airlines and Tourism ltd) 57099 6N 6N Trans Travel Airlines (Dump) 11099 6Q 6Q Slovak Airlines 30499 6U 6U Air Ukraine 32201 7B 7B Kras Air (Dump) 30999 7G 7G MK Airlines (Dump) 01099 7L 7L Sun d'Or International 57099 7W 7W Air Sask 80099 7Y 7Y EAE European Air Express 08099 8A 8A Atlas Blue 35299 8F 8F Fischer Air 30399 8L 8L Newair (Dump) 12099 8Q 8Q Onur Air (Dump) 16099 8U 8U Afriqiyah Airways 35199 9C 9C Gill Aviation (Dump) 01099 9G 9G Galaxy Airways (Dump) 22099 9L 9L Colgan Air (Dump) 81099 9P 9P Pelangi Air (Dump) 60599 9R 9R Phuket Airlines 66499 9S 9S Blue Panorama Airlines 10099 9U 9U Air Moldova (Dump) 31999 9W 9W Jet Airways (Dump) 61099 9Y 9Y Air Kazakstan (Dump) 31599 A3 A3 Aegean Airlines 22099 A7 A7 Air Plus Comet 25099 AA AA American Airlines 81028 AAA1 AAA Ansett Air Australia (Dump) 50099 AAA2 AAA Ansett New Zealand (Dump) -

Moreton, Woodsford and Crossways with Tincleton Benefice Profile 2020

MORETON, WOODSFORD AND CROSSWAYS WITH TINCLETON BENEFICE PROFILE 2020 Benefice Profile - Crossways docx final 2020 Page 1 Contents 1. Introduction to the Profile by the Bishop of Sherborne 3 2. General Description of the Benefice 4 3. What we are looking for in our new Rector 5 4. A Snapshot of the Benefice 6 5 The Churches in our Benefice 7 5.1 St. Nicholas, Moreton 7 5.2 St. John the Baptist, Woodsford 8 5.3. St. Aldhelm, Crossways 9 5.4. St. John the Evangelist, Tincleton 10 6. School Link 11 7. The Rectory and Local Area 12 8. The Dorchester Deanery 13 9. What we can offer You 14 Benefice Profile - Crossways docx final 2020 Page 2 1. Introduction to the Profile by the Bishop of Sherborne In Dorset we have been working hard to make rural ministry both a joy and a delight. In recent years significant changes have been made in the way clergy are supported and encouraged, leading to a greater sense of collegiality in our rural and our urban areas. The Dorchester Deanery, in which the Benefice is situated, seeks to be a supportive place bringing together the rural clergy with those in the County Town. There will be a warm welcome amongst this clergy grouping for whoever comes to this Benefice. The parishes here enjoy beautiful rural countryside yet are within easy reach of Dorchester. Whilst some of these parishes remain as they have been for hundreds of years, and contain some exquisite churches, Crossways, in particular, is an expanding village aimed at attracting a mixed population, including a large number of families, and the newly built church here, adjacent to the school, creates a significant opportunity for the church to open its doors to minister to all those who live in that community. -

Dorset History Centre

GB 0031 MK Dorset History Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 5598 The National Archives DORSET RECORD OFFICE MK Documents presented to the Dorchester County Museum by Messrs. Traill, Castleman-Smith and Wilson in 1954. DLEDS. N " J Bundle No Date Description of Documents of Documents AFFPUDDLE Tl 1712 Messuage, Cottage and land. 1 BSLCHALWELL and IB3ERT0I? a T2 1830 Land in Fifehead Quinton in Belchalwell and messuage called Quintons in Ibberton; part of close called Allinhere in Ibberton. (Draftsj* 2 BELCHALWELL * * T3 1340 i Cottage (draft); with residuary account of Mary Robbins. 2 BERE REGIS K T4 1773-1781 Cottage and common rights at Shitterton, 1773; with papers of Henry Hammett of the same, including amusing letter complaining of 'Divels dung1 sold to hira, 1778-1731. 11 Messuage at Rye Hill X5 1781-1823 3 a T6 1814-1868 2 messuages, at some time before 1853 converted into one, at iiilborne Stilehara. ' 9 T7 1823-1876 Various properties including cottage in White Lane, Milborne Stileham. 3 BLAHDFOIiD FORUM T8 1641-1890 Various messuages in Salisbury Street, including the Cricketers Arms (1826) and the houses next door to the Bell Inn. (1846,1347) 14 *T9 1667-1871 Messuages in Salisbury Street, and land "whereon there , stood before the late Dreadful Fire a messuage1 (1736) in sane street, 1667-1806, with papers,; 1316-71. 21 TIG 168^6-1687/8 Messuage in Salisbury Street (Wakeford family) A Til 1737-1770 Land in Salisbury Street. (Bastard family) J 2 212 1742-1760 Land in Salisbury Street, with grant to rest timbers on a wall there. -

November 2019

WHAT’S ON in and around November 2019 WEST DORSET This listing contains a selection of events taking place across West Dorset this month. For full event information pop into your local TIC Don’t miss this month… WEST DORSET Cards for Good Causes – all TICs Fireworks 02-08 Bridport Literary Festival 03-09 Christmas Lights Launches 30 HIGHLIGHTS Fossil Walks Regular guided fossil hunting walks in Lyme Regis & Charmouth are run year round by Lyme Regis Museum 01297 443370 www.lymeregismuseum.co.uk, Brandon Lennon 07944 664757 www.lymeregisfossilwalks.com Jurassic Gems 01297 444405, the Charmouth Heritage Coast Centre 01297 560772 www.charmouth.org, Jurassic Coast Guides 07900 257944 [email protected] Chris Pamplin 0845 0943757 www.fossilwalks.com Times vary according to the tides, telephone for full details & booking information. Walking the Way to Health in Bridport, with trained health walk leaders. Starts from CAB, 45 South Street every Tues & Thurs at 10:30am. Walks last approx 30mins, all welcome, free of charge. 01305 252222 or [email protected] Durotriges Roman Tours Every day at Town Pump: 11am, 1pm & 4pm. A£8 C£4 from Dorchester TIC 07557472092 Booking Essential [email protected] Dorchester Strollers, walks with trained health walkers. Every Mon at 10:30am & Tues at 2:15pm. Occasional Thurs & Sun afternoons. Walks last up to one hour, all welcome, free. 01305 263759 for more information. Literary Lyme walking tours available throughout the year. 07763 974569 for details & to book. Mary Anning Walks Lyme Regis. Old Lyme as Mary knew it with Natalie Manifold. 01297 443370.