This Electronic Thesis Or Dissertation Has Been Downloaded from the King’S Research Portal At

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lord Lyon King of Arms

VI. E FEUDAE BOBETH TH F O LS BABONAG F SCOTLANDO E . BY THOMAS INNES OP LEABNEY AND KINNAIRDY, F.S.A.ScoT., LORD LYON KIN ARMSF GO . Read October 27, 1945. The Baronage is an Order derived partly from the allodial system of territorial tribalis whicn mi patriarce hth h hel s countrydhi "under God", d partlan y froe latemth r feudal system—whic e shale wasw hse n li , Western Europe at any rate, itself a developed form of tribalism—in which the territory came to be held "of and under" the King (i.e. "head of the kindred") in an organised parental realm. The robes and insignia of the Baronage will be found to trace back to both these forms of tenure, which first require some examination from angle t usuallno s y co-ordinatedf i , the later insignia (not to add, the writer thinks, some of even the earlier understoode symbolsb o t e )ar . Feudalism has aptly been described as "the development, the extension organisatione th y sa y e Family",o familyth fma e oe th f on n r i upon,2o d an Scotlandrelationn i Land;e d th , an to fundamentall o s , tribaa y l country, wher e predominanth e t influences have consistently been Tribality and Inheritance,3 the feudal system was immensely popular, took root as a means of consolidating and preserving the earlier clannish institutions,4 e clan-systeth d an m itself was s modera , n historian recognisew no s t no , only closely intermingled with feudalism, but that clan-system was "feudal in the strictly historical sense".5 1 Stavanger Museums Aarshefle, 1016. -

GREY FILLY Foaled 4Th May 2014

GREY FILLY Foaled 4th May 2014 Sire Ishiguru Danzig...................................Northern Dancer HELLVELYN Strategic Maneuver ..............Cryptoclearance 2004 Cumbrian Melody Petong..............................................Mansingh Avahra.....................................................Sahib Dam Bin Ajwaad Rainbow Quest..................... Blushing Groom ELDERBERRY Salidar................................................... Sallust 1997 Silver Berry Lorenzaccio ..........................................Klairon Queensberry...........................Grey Sovereign HELLVELYN (GB) (Grey 2004-Stud 2011). 5 wins-3 at 2-at 5f, 6f, Royal Ascot Coventry S., Gr.2. Sire of 92 rnrs, 37 wnrs, inc. SW Mrs Danvers (Newmarket Cornwallis S., Gr.3), La Rioja, SP Bonnie Grey, Hellofahaste, Mister Trader and of Melaniemillie, Koral Power, Doc Charm, Ormskirk, Prince Hellvelyn, Charlie's Star, White Vin Jan, Quench Dolly, Here's Two, Himalaya, Swirral Edge, Twentysvnthlancers, Ellenvelyn, Grosmont, Mountain Man, etc. 1st dam ELDERBERRY, by Bin Ajwaad. Raced once. Half-sister to ARGENTUM, Grey Regal, Pipsqueak. This is her eighth foal. Dam of six foals to race, four winners, inc:- The Grey Berry (g. by Observatory). 5 wins from 1m to 2m, Ayr Knight Frank H., 2d York Parsonage Country House Hotel H. Billberry (g. by Diktat). 4 wins at 6f, 7f, 2d Newmarket Racing Welfare Grey Horse H., 3d Newmarket Soccer Saturday Super 6 H. Glastonberry (f. by Piccolo). 8 wins to 7f. Fisberry (g. by Efisio). 2 wins at 6f. 2nd dam SILVER BERRY, by Lorenzaccio. Unplaced. Half-sister to CRANBERRY SAUCE (dam of SAUCEBOAT), Absalom, Kingsberry, Queenborough II, Checkerberry (dam of CHECKER EXPRESS). Dam of 12 foals, 5 to race, 4 winners, inc:- ARGENTUM (Aragon). 5 wins-3 at 2-at 5f, 6f, Ascot Cornwallis S., Gr.3, Goodwood King George S., Gr.3. Grey Regal (Be My Chief). -

Download Thesis

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from the King’s Research Portal at https://kclpure.kcl.ac.uk/portal/ Fast Horses The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 - 1920 Harper, Esther Fiona Awarding institution: King's College London The copyright of this thesis rests with the author and no quotation from it or information derived from it may be published without proper acknowledgement. END USER LICENCE AGREEMENT Unless another licence is stated on the immediately following page this work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International licence. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ You are free to copy, distribute and transmit the work Under the following conditions: Attribution: You must attribute the work in the manner specified by the author (but not in any way that suggests that they endorse you or your use of the work). Non Commercial: You may not use this work for commercial purposes. No Derivative Works - You may not alter, transform, or build upon this work. Any of these conditions can be waived if you receive permission from the author. Your fair dealings and other rights are in no way affected by the above. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 10. Oct. 2021 Fast Horses: The Racehorse in Health, Disease and Afterlife, 1800 – 1920 Esther Harper Ph.D. History King’s College London April 2018 1 2 Abstract Sports historians have identified the 19th century as a period of significant change in the sport of horseracing, during which it evolved from a sporting pastime of the landed gentry into an industry, and came under increased regulatory control from the Jockey Club. -

The Green Ribbon

The Green Ribbon By Edgar Wallace The Green Ribbon CHAPTER I. WALKING up Lower Regent Street at his leisure, Mr. Luke saw the new business block which had been completed during his absence in South America and paused, his hands thrust into his trousers pockets, to examine the new home of the wealth-bringer. On each big plate-glass window of the first and second floor were two gilt T's intertwined, and above each a green ribbon twisted scroll in t form of a Gordian knot. He grinned slowly. It was so decorous and unostentatious and businesslike. No flaming banners or hectic posters, no shouting lithographs to call attention to the omniscience of Mr. Joe Trigger and his Transactions. Just the two gilt T's and the green ribbon that went so well with the marble doorway and the vista of little mahogany desks and the ranks of white glass ceiling lamps above them. It might have been a bank or a shipping office. He took a newspaper out of his pocket and opened it. It was a sporting daily and on the middle page was a four-column advertisement: TRIGGER'S TRANSACTIONS Number 7 will run between September 1st and 15th. Subscribers are requested to complete their arrangements before the earlier date. Books will close at noon on August 31st and will not be reopened before noon September 16th. Gentlemen of integrity who wish to join the limited list of patrons should apply: The Secretary, Trigger's Transactions, Incorporated At the Sign of the Green Ribbon, 704 Lower Regent St., W.1. -

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad

High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad High Performance Stallions Standing Abroad An extract from the Irish Sport Horse Studbook Stallion Book The Irish Sport Horse Studbook is maintained by Horse Sport Ireland and the Northern Ireland Horse Board Horse Sport Ireland First Floor, Beech House, Millennium Park, Osberstown, Naas, Co. Kildare, Ireland Telephone: 045 850800. Int: +353 45 850800 Fax: 045 850850. Int: +353 45 850850 Email: [email protected] Website: www.horsesportireland.ie Northern Ireland Horse Board Office Suite, Meadows Equestrian Centre Embankment Road, Lurgan Co. Armagh, BT66 6NE, Northern Ireland Telephone: 028 38 343355 Fax: 028 38 325332 Email: [email protected] Website: www.nihorseboard.org Copyright © Horse Sport Ireland 2015 HIGH PERFORMANCE STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD INDEX OF APPROVED STALLIONS BY BREED HIGH PERFORMANCE RECOGNISED FOREIGN BREED STALLIONS & STALLIONS STALLIONS STANDING ABROAD & ACANTUS GK....................................4 APPROVED THROUGH AI ACTION BREAKER.............................4 BALLOON [GBR] .............................10 KROONGRAAF............................... 62 AIR JORDAN Z.................................. 5 CANABIS Z......................................18 LAGON DE L'ABBAYE..................... 63 ALLIGATOR FONTAINE..................... 6 CANTURO.......................................19 LANDJUWEEL ST. HUBERT ............ 64 AMARETTO DARCO ......................... 7 CASALL LA SILLA.............................22 LARINO.......................................... 66 -

From Confey Stud the Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner Busted

From Confey Stud 1275 The Property of Mr. Gervin Creaner 1275 Crepello Busted Sans Le Sou Shernazar Val de Loir SHERAMIE (IRE) Sharmeen (1992) Nasreen Bay Mare Vaguely Noble Gracieuse Amie Gay Mecene Gay Missile (FR) Habitat (1986) Gracious Glaneuse 1st dam GRACIEUSE AMIE (FR): placed 4 times at 3 in France; Own sister to GAY MINSTREL (FR); dam of 4 winners inc.: Euphoric (IRE): 6 wins and £29,957 and placed 15 times. Groupie (IRE): 2 wins at 3 and 4 in Brazil; dam of 4 winners inc.: GREETINGS (BRZ) (f. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 3 wins in Brazil inc. Grande Premio Paulo Jose da Costa, Gr.3. GRISSINI (BRZ) (c. by Choctaw Ridge (USA)): 9 wins in Brazil inc. Classico Renato Junqueira Netto, L. 2nd dam GRACIOUS: 3 wins at 2 and 3 in France and placed; dam of 7 winners inc.: GAY MINSTREL (FR) (c. by Gay Mecene (USA)): 6 wins in France and 922,500 fr. inc. Prix Messidor, Gr.3, Prix Perth, Gr.3; sire. GREENWAY (FR) (f. by Targowice (USA)): 3 wins at 2 in France and 393,000 fr. inc. Prix d'Arenberg, Gr.3 and Prix du Petit Couvert, Gr.3, 2nd Prix des Reves d'Or, L. and 4th Prix de Saint-Georges, Gr.3; dam of 6 winners inc.: WAY WEST (FR): 3 wins at 3 and 4 in France and 693,600 fr. inc. Prix Servanne, L., 3rd Prix du Gros-Chene, Gr.2; sire. Green Gold (FR): 10 wins in France, 2nd Prix Georges Trabaud, L. Gerbera (USA): winner in France; dam of RENASHAAN (FR) (won Prix Casimir Delamarre, L.); grandam of ALEXANDER GOLDRUN (IRE), (Champion older mare in Ireland in 2005, 10 wins to 2006 at home, in France and in Hong Kong and £1,901,150 inc. -

O=Brien Shares Update on Dwc Night Squad

SUNDAY, 15 MARCH 2020 O=BRIEN SHARES UPDATE FRANCE CLOSES ALL NON-ESSENTIAL BUSINESSES, RACECOURSES REMAIN OPEN ON DWC NIGHT SQUAD FOR NOW At 8 p.m. Saturday evening, French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe announced stricter social distancing measures due to the coronavirus, and that all places non-essential to French living including restaurants, cafes, cinemas and clubs, will be closed beginning at midnight on Saturday, Jour de Galop reported. At this time, French racecourses, which are currently racing without spectators for the foreseeable future, will remain open. France Galop=s President Edouard de Rothschild and Managing Director Olivier Delloye both confirmed late Saturday evening to the JDG that racing will continue in Aclosed camera@ mode, but that the situation remains delicate. France=s PMU is affected by the closure, as all businesses where the PMU operates that does not also have the designation of cafJ, must be shuttered. Kew Gardens | Mathea Kelley Irish and German racing is also currently being conducted without spectators, while racing in the UK has proceeded very Coolmore=s Kew Gardens (Ire) (Galileo {Ire}), who snapped much as normal. All Italian racing has been suspended until at champion stayer Stradivarius (Ire) (Sea The Stars {Ire})=s winning least Apr. 3, as the entire country is in lock down. streak in the G2 Long Distance Cup on British Champions Day at Ascot in October, will make his 2020 bow in the $1.5-million G2 Dubai Gold Cup. The Aidan O=Brien trainee, who won the 2018 G1 Grand Prix de Paris as well as the G1 St Leger during his 3- year-old year, was never off the board in four starts last term, running second three timesBin the G3 Ormonde S. -

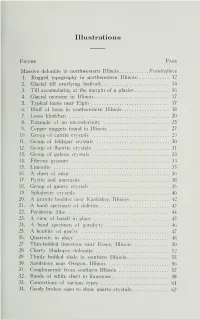

TYPICAL ROCKS and MINERALS in ILLINOIS By

Illustrations Figure Page Massive dolomite in northwestern Illinois Frontispiece 1. Rugged topography in northwestern Illinois 12 2. Glacial till overlying bedrock 14 3. Till accumulating at the margin of a glacier 16 4. Glacial moraine in Illinois 17 5. Typical kame near Elgin 17 6. Bluff of loess in southwestern Illinois 18 7. Loess kindchen 20 8. Example of an unconformity 25 9. Copper nuggets found in Illinois 27 10. Group of calcite crystals 29 11. Group of feldspar crystals 30 12. Group of fluorite crystals 31 13. Group of galena crystals 33 14. Fibrous gypsum 31 15. Limonite 35 16. A sheet of mica 36 17. Pyrite and marcasite 38 18. Group of quartz crystals 39 19. Sphalerite crystals 40 20. A granite boulder near Kankakee, Illinois 42 21. A hand specimen of dolerite 43 22. Peridotite dike 44 23. A view of basalt in place 45 24. A hand specimen of i)()ri)hyry 46 25. A boulder of gneiss 47 26. Ouartzite in place 48 27. Thin-bedded limestone near Essex, Illinois 50 28 Cherty Shakopce dolomite 52 29. Thinly bedded shale in southern Illinois 55 30. Sandstone near Oregon, Illinois 56 31. Conglomerate from southern Illinois 57 32. Bands of white chert in limestone 58 33. Concretions of various types 61 34. Geode broken open to show quartz crystals 62 k^^H L 1 -= 1=^ U.S.A. -^^^H \ ^ r ^ ^1 1 L i ^H E «; -H iiTn 11 i|i|i i|i|i|i i| ;co. 1 u.s A. 2 •l A Gvdl tiu*».ot«u^ Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2012 with funding from University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign http://archive.org/details/typicalrocksmine03ekbl CQ O ?: -5 ^ a be ^ STATE OF ILLINOIS DEPARTMENT OF REGISTRATION AND EDUCATION STATE GEOLOGICAL SURVEY M. -

ALL the PRETTY HORSES.Hwp

ALL THE PRETTY HORSES Cormac McCarthy Volume One The Border Trilogy Vintage International• Vintage Books A Division of Random House, Inc. • New York I THE CANDLEFLAME and the image of the candleflame caught in the pierglass twisted and righted when he entered the hall and again when he shut the door. He took off his hat and came slowly forward. The floorboards creaked under his boots. In his black suit he stood in the dark glass where the lilies leaned so palely from their waisted cutglass vase. Along the cold hallway behind him hung the portraits of forebears only dimly known to him all framed in glass and dimly lit above the narrow wainscotting. He looked down at the guttered candlestub. He pressed his thumbprint in the warm wax pooled on the oak veneer. Lastly he looked at the face so caved and drawn among the folds of funeral cloth, the yellowed moustache, the eyelids paper thin. That was not sleeping. That was not sleeping. It was dark outside and cold and no wind. In the distance a calf bawled. He stood with his hat in his hand. You never combed your hair that way in your life, he said. Inside the house there was no sound save the ticking of the mantel clock in the front room. He went out and shut the door. Dark and cold and no wind and a thin gray reef beginning along the eastern rim of the world. He walked out on the prairie and stood holding his hat like some supplicant to the darkness over them all and he stood there for a long time. -

Scatter Dice Seemed to Have Blown Her Chance at the Start

THOSE GOLDEN MO MENTS This year, the Klarion is taking a look back at some of the Longchamp; and Domination, who had horses and races that made the 2010s so special for prepared for the race by winning two decent hurdle events at Cork in August. Johnston Racing. This month, we turn the spotlight on a filly Scatter Dice seemed to have blown her chance at the start. Drawn in stall 18, she whose golden moment came at Newmarket in October 2013. crawled out of the stalls. Silvestre immediately switched her to the inner rail, but she looked to have conceded the best Y any standards, the Hamdan bin Mohammed and bred by she was winless, though she had part of 10 lengths as a start to rivals. Cesarewitch is a unique horse Darley, she was by the triple Group 1 substantially run well up to her handicap All three Johnston horses were towards B race. Run over a distance of two winner Manduro (Prix Jacques le mark and had finished second once, and the rear of the field in the early stages. miles two furlongs at Marois/Prince of Wales’s Stakes/Prix third three times. Scatter Dice was kept to the inner and The winning filly Scatter Dice with Mark, jockey Silvestre de Sousa Newmarket, the race starts in d’Ispahan) out of the Soviet Star mare, Scatter Dice was one of three Johnston- gradually made her way into the race. With and groom Shrawan Singh Cambridgeshire, follows an ‘L’ shape Sensation. The dam, who raced in France trained runners in the race. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

History of the Ormonde

WELCOME TO THE ORMONDE GUESTHOUSE THE ORMONDE GUESTHOUSE HISTORY Former Railway Tavern public house, later renamed as the Ormonde tavern. Late 19th, early 20th century. Two storey, 3 bay semi symmetrical arrangement with projecting terminal end bays, timber framed gables to projecting bays. Slate roof, 1st floor timber framed. Ground floor Ruabon brick with stone dressings to window heads, cheeks and cills, casement windows with leaded transome lights. This building is now the Ormonde Hotel. "Ormonde" (1883–1904) was an English Thoroughbred racehorse, an unbeaten Triple Crown winner, generally considered to be one of the greatest racehorses ever. He also won the Champion Stakes and the Hardwicke Stakes twice. At the time he was often labeled as the 'horse of the century'. Ormonde was trained at Kingsclere by John Porter for the 1st Duke of Westminster. His regular jockeys were Fred Archer (who features on the sign outside the hotel in the correct colours) and Tom Cannon. After retiring from racing he suffered fertility problems, but still sired Orme, who won the Eclipse Stakes twice. It has been suggested that "Ormonde's" sire was the model for "Silver Blaze" in the Sherlock Holmes story of the same name, first published 1892. In the same way, "Colonel Ross" in the story is said to be based on one of the Grosvenors - the first Duke of Westminster. Eaton Stud bred "Ormonde" with Fred Archer up. Fred Archer (1857-86) had 21 Classic winners and was Champion Jockey 13 of his 17 years, before tragically committing suicide in 1886. To keep his weight down for racing he used "Archer's mixture", a powerful laxitive made up by Dr J.