Why Am I Reading This? Book List

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist A

Many Voices, One Nation Booklist Many Voices, One Nation began as an initiative of past American Library Association President Carol Brey-Casiano. In 2005 ALA Chapters, Ethnic Caucuses, and other ALA groups were asked to contribute annotated book selections that best represent the uniqueness, diversity, and/or heritage of their state, region or group. Selections are featured for children, young adults, and adults. The list is a sampling that showcases the diverse voices that exist in our nation and its literature. A Alabama Library Association Title: Send Me Down a Miracle Author: Han Nolan Publisher: San Diego: Harcourt Brace Date of Publication: 1996 ISBN#: [X] Young Adults Annotation: Adrienne Dabney, a flamboyant New York City artist, returns to Casper, Alabama, the sleepy, God-fearing town of her birth, to conduct an artistic experiment. Her big-city ways and artsy ideas aren't exactly embraced by the locals, but it's her claim of having had a vision of Jesus that splits the community. Deeply affected is fourteen- year-old Charity Pittman, daughter of a local preacher. Reverend Pittman thinks Adrienne is the devil incarnate while Charity thinks she's wonderful. Believer is pitted against nonbeliever and Charity finds herself caught in the middle, questioning her father, her religion, and herself. Alabama Library Association Title: Fried Green Tomatoes at the Whistle Stop Café Author: Fannie Flagg Publisher: New York: Random House Date of Publication: 1987 ISBN#: [X] Adults Annotation: This begins as the story of two women in the 1980s, of gray-headed Mrs. Threadgoode telling her life story to Evelyn who is caught in the sad slump of middle age. -

Deadlands: Reloaded Core Rulebook

This electronic book is copyright Pinnacle Entertainment Group. Redistribution by print or by file is strictly prohibited. This pdf may be printed for personal use. The Weird West Reloaded Shane Lacy Hensley and BD Flory Savage Worlds by Shane Lacy Hensley Credits & Acknowledgements Additional Material: Simon Lucas, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys Editing: Simon Lucas, Dave Blewer, Piotr Korys, Jens Rushing Cover, Layout, and Graphic Design: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Thomas Denmark Typesetting: Simon Lucas Cartography: John Worsley Special Thanks: To Clint Black, Dave Blewer, Kirsty Crabb, Rob “Tex” Elliott, Sean Fish, John Goff, John & Christy Hopler, Aaron Isaac, Jay, Amy, and Hayden Kyle, Piotr Korys, Rob Lusk, Randy Mosiondz, Cindi Rice, Dirk Ringersma, John Frank Rosenblum, Dave Ross, Jens Rushing, Zeke Sparkes, Teller, Paul “Wiggy” Wade-Williams, Frank Uchmanowicz, and all those who helped us make the original Deadlands a premiere property. Fan Dedication: To Nick Zachariasen, Eric Avedissian, Sean Fish, and all the other Deadlands fans who have kept us honest for the last 10 years. Personal Dedication: To mom, dad, Michelle, Caden, and Ronan. Thank you for all the love and support. You are my world. B.D.’s Dedication: To my parents, for everything. Sorry this took so long. Interior Artwork: Aaron Acevedo, Travis Anderson, Chris Appel, Tom Baxa, Melissa A. Benson, Theodor Black, Peter Bradley, Brom, Heather Burton, Paul Carrick, Jim Crabtree, Thomas Denmark, Cris Dornaus, Jason Engle, Edward Fetterman, -

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT of INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION in Re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMEN

USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 1 of 354 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT NORTHERN DISTRICT OF INDIANA SOUTH BEND DIVISION ) Case No. 3:05-MD-527 RLM In re FEDEX GROUND PACKAGE ) (MDL 1700) SYSTEM, INC., EMPLOYMENT ) PRACTICES LITIGATION ) ) ) THIS DOCUMENT RELATES TO: ) ) Carlene Craig, et. al. v. FedEx Case No. 3:05-cv-530 RLM ) Ground Package Systems, Inc., ) ) PROPOSED FINAL APPROVAL ORDER This matter came before the Court for hearing on March 11, 2019, to consider final approval of the proposed ERISA Class Action Settlement reached by and between Plaintiffs Leo Rittenhouse, Jeff Bramlage, Lawrence Liable, Kent Whistler, Mike Moore, Keith Berry, Matthew Cook, Heidi Law, Sylvia O’Brien, Neal Bergkamp, and Dominic Lupo1 (collectively, “the Named Plaintiffs”), on behalf of themselves and the Certified Class, and Defendant FedEx Ground Package System, Inc. (“FXG”) (collectively, “the Parties”), the terms of which Settlement are set forth in the Class Action Settlement Agreement (the “Settlement Agreement”) attached as Exhibit A to the Joint Declaration of Co-Lead Counsel in support of Preliminary Approval of the Kansas Class Action 1 Carlene Craig withdrew as a Named Plaintiff on November 29, 2006. See MDL Doc. No. 409. Named Plaintiffs Ronald Perry and Alan Pacheco are not movants for final approval and filed an objection [MDL Doc. Nos. 3251/3261]. USDC IN/ND case 3:05-md-00527-RLM-MGG document 3279 filed 03/22/19 page 2 of 354 Settlement [MDL Doc. No. 3154-1]. Also before the Court is ERISA Plaintiffs’ Unopposed Motion for Attorney’s Fees and for Payment of Service Awards to the Named Plaintiffs, filed with the Court on October 19, 2018 [MDL Doc. -

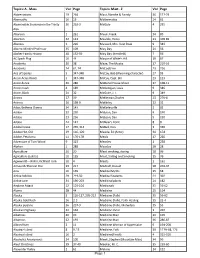

California Folklore Miscellany Index

Topics: A - Mass Vol Page Topics: Mast - Z Vol Page Abbreviations 19 264 Mast, Blanche & Family 36 127-29 Abernathy 16 13 Mathematics 24 62 Abominable Snowman in the Trinity 26 262-3 Mattole 4 295 Alps Abortion 1 261 Mauk, Frank 34 89 Abortion 22 143 Mauldin, Henry 23 378-89 Abscess 1 226 Maxwell, Mrs. Vest Peak 9 343 Absent-Minded Professor 35 109 May Day 21 56 Absher Family History 38 152-59 May Day (Kentfield) 7 56 AC Spark Plug 16 44 Mayor of White's Hill 10 67 Accidents 20 38 Maze, The Mystic 17 210-16 Accidents 24 61, 74 McCool,Finn 23 256 Ace of Spades 5 347-348 McCoy, Bob (Wyoming character) 27 93 Acorn Acres Ranch 5 347-348 McCoy, Capt. Bill 23 123 Acorn dance 36 286 McDonal House Ghost 37 108-11 Acorn mush 4 189 McGettigan, Louis 9 346 Acorn, Black 24 32 McGuire, J. I. 9 349 Acorns 17 39 McKiernan,Charles 23 276-8 Actress 20 198-9 McKinley 22 32 Adair, Bethena Owens 34 143 McKinleyville 2 82 Adobe 22 230 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 23 236 McLean, Dan 9 190 Adobe 24 147 McNear's Point 8 8 Adobe house 17 265, 314 McNeil, Dan 3 336 Adobe Hut, Old 19 116, 120 Meade, Ed (Actor) 34 154 Adobe, Petaluma 11 176-178 Meals 17 266 Adventure of Tom Wood 9 323 Measles 1 238 Afghan 1 288 Measles 20 28 Agriculture 20 20 Meat smoking, storing 28 96 Agriculture (Loleta) 10 135 Meat, Salting and Smoking 15 76 Agwiworld---WWII, Richfield Tank 38 4 Meats 1 161 Aimee McPherson Poe 29 217 Medcalf, Donald 28 203-07 Ainu 16 139 Medical Myths 15 68 Airline folklore 29 219-50 Medical Students 21 302 Airline Lore 34 190-203 Medicinal plants 24 182 Airplane -

Formulating Western Fiction in Garrett Touch of Texas

AWEJ for Translation & Literary Studies, Volume 2, Number 2, May 2018 Pp. 142 -155 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awejtls/vol2no2.10 Formulating Western Fiction in Garrett Touch of Texas Elisabeth Ngestirosa Endang Woro Kasih Faculty of Art and Education, Universitas Teknokrat Indonesia, Bandarlampung, Indonesia Abstract Western fiction as one of the popular novels has some common conventions such as the setting of life in frontier filled with natural ferocity and uncivilized people. This type of fiction also has a hero who is usually a ranger or cowboy. This study aims to find a Western fiction formula and look for new things that may appear in the novel Touch of Texas as a Western novel. Taking the original convention of Cooper’s Leatherstocking Tales, this study also looks for the invention and convention of Touch of Texas by using Cawelti’s formula theory. The study finds that Garrett's Touch of Texas not only features a natural malignancy against civilization, a ranger as a single hero, and a love story, but also shows an element of revenge and the other side of a neglected minority life. A hero or ranger in this story comes from a minority group, a mixture of white blood and Indians. The romance story also shows a different side. The woman in the novel is not the only one to be saved, but a Ranger is too, especially from the wounds and ridicule of the population as a ranger of mixed blood. The story ends with a romantic tale between Jake and Rachel. Further research can be done to find the development of western genre with other genres such as detective and mystery. -

Tragedy After Darwin by Manya Lempert a Dissertation Submitted In

Tragedy after Darwin by Manya Lempert A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Professor Ann Banfield Professor Catherine Gallagher Professor Barry Stroud Summer 2015 Abstract Tragedy after Darwin by Manya Lempert Doctor of Philosophy in English University of California, Berkeley Professor Dorothy Hale, Chair Tragedy after Darwin is the first study to recognize novelistic tragedy as a sub-genre of British and European modernism. I argue that in response to secularizing science, authors across Europe revive the worldview of the ancient tragedians. Hardy, Woolf, Pessoa, Camus, and Beckett picture a Darwinian natural world that has taken the gods’ place as tragic antagonist. If Greek tragic drama communicated the amorality of the cosmos via its divinities and its plots, the novel does so via its characters’ confrontations with an atheistic nature alien to redemptive narrative. While the critical consensus is that Darwinism, secularization, and modernist fiction itself spell the “death of tragedy,” I understand these writers’ oft-cited rejection of teleological form and their aesthetics of the momentary to be responses to Darwinism and expressions of their tragic philosophy: characters’ short-lived moments of being stand in insoluble conflict with the expansive time of natural and cosmological history. The fiction in this study adopts an anti-Aristotelian view of tragedy, in which character is not fate; character is instead the victim, the casualty, of fate. And just as the Greek tragedians depict externally wrought necessity that is also divorced from mercy, from justice, from theodicy, Darwin’s natural selection adapts species to their environments, preserving and destroying organisms, with no conscious volition and no further end in mind – only because of chance differences among them. -

Made in America: Exploring the Hollywood Western Red River (1948) – Introductory Lecture

MADE IN AMERICA: EXPLORING THE HOLLYWOOD WESTERN RED RIVER (1948) – INTRODUCTORY LECTURE TRANSCRIPT Introductory Lecture: Red River (1948) Welcome to the Western. I’m glad you can be here today. Red River (1948) is a 1948 Western film produced by Howard Hawks and starring John Wayne and Montgomery Clift. The film’s supporting cast features Walter Brennan, Joanne Dru, Colleen Gray, Harry Carey, John Ireland, Hank Worden, Noah Beery, Jr., Harry Carey Jr., and Paul Fix. The screenplay was based on Borden Chase’s original story which was first serialized in The Saturday Evening Post in 1946 as “Blazing Guns on the Chisholm Trail.” The movie’s ending differs from that of the original story. In Chase’s Saturday Evening Post’s story, Cherry Valance shoots Tom Dunson dead in Abilene and Matt takes his body back to Texas to be buried on the ranch. Red River cost an estimated $3 million to make it did very well at the box office. In 1948, it grossed $5 and a half million domestically and worldwide it made over $9 million. It was a very, very popular movie. The film is also an art movie. It was nominated for Academy Awards for Best Film Editing by Christian Nyby and Best Writing Motion Picture Story by Borden Chase. John Ford was so impressed with John Wayne’s performance in Red River that he is reported to have said I didn’t know the big son of a bitch could act. In June 2008, the American Film Institute listed Red River as the fifth best film in the Western genre. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature As Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012

Teaching Skills with Children's Literature as Mentor Text Presented at TLA 2012 List compiled by: Michelle Faught, Aldine ISD, Sheri McDonald, Conroe ISD, Sally Rasch, Aldine ISD, Jessica Scheller, Aldine ISD. April 2012 2 Enhancing the Curriculum with Children’s Literature Children’s literature is valuable in the classroom for numerous instructional purposes across grade levels and subject areas. The purpose of this bibliography is to assist educators in selecting books for students or teachers that meet a variety of curriculum needs. In creating this handout, book titles have been listed under a skill category most representative of the picture book’s story line and the author’s strengths. Many times books will meet the requirements of additional objectives of subject areas. Summaries have been included to describe the stories, and often were taken directly from the CIP information. Please note that you may find some of these titles out of print or difficult to locate. The handout is a guide that will hopefully help all libraries/schools with current and/or dated collections. To assist in your lesson planning, a subjective rating system was given for each book: “A” for all ages, “Y for younger students, and “O” for older students. Choose books from the list that you will feel comfortable reading to your students. Remember that not every story time needs to be a teachable moment, so you may choose to use some of the books listed for pure enjoyment. The benefits of using children’s picture books in the instructional setting are endless. The interesting formats of children’s picture books can be an excellent source of information, help students to understand vocabulary words in different contest areas, motivate students to learn, and provide models for research and writing. -

Award Winners

Award Winners Agatha Awards 1992 Boot Legger’s Daughter 2005 Dread in the Beast Best Contemporary Novel by Margaret Maron by Charlee Jacob (Formerly Best Novel) 1991 I.O.U. by Nancy Pickard 2005 Creepers by David Morrell 1990 Bum Steer by Nancy Pickard 2004 In the Night Room by Peter 2019 The Long Call by Ann 1989 Naked Once More Straub Cleeves by Elizabeth Peters 2003 Lost Boy Lost Girl by Peter 2018 Mardi Gras Murder by Ellen 1988 Something Wicked Straub Byron by Carolyn G. Hart 2002 The Night Class by Tom 2017 Glass Houses by Louise Piccirilli Penny Best Historical Mystery 2001 American Gods by Neil 2016 A Great Reckoning by Louise Gaiman Penny 2019 Charity’s Burden by Edith 2000 The Traveling Vampire Show 2015 Long Upon the Land Maxwell by Richard Laymon by Margaret Maron 2018 The Widows of Malabar Hill 1999 Mr. X by Peter Straub 2014 Truth be Told by Hank by Sujata Massey 1998 Bag of Bones by Stephen Philippi Ryan 2017 In Farleigh Field by Rhys King 2013 The Wrong Girl by Hank Bowen 1997 Children of the Dusk Philippi Ryan 2016 The Reek of Red Herrings by Janet Berliner 2012 The Beautiful Mystery by by Catriona McPherson 1996 The Green Mile by Stephen Louise Penny 2015 Dreaming Spies by Laurie R. King 2011 Three-Day Town by Margaret King 1995 Zombie by Joyce Carol Oates Maron 2014 Queen of Hearts by Rhys 1994 Dead in the Water by Nancy 2010 Bury Your Dead by Louise Bowen Holder Penny 2013 A Question of Honor 1993 The Throat by Peter Straub 2009 The Brutal Telling by Louise by Charles Todd 1992 Blood of the Lamb by Penny 2012 Dandy Gilver and an Thomas F. -

The Chisholm Trail

From the poem “Cattle” by Berta Hart Nance In the decades following the Civil War, more than 6 million cattle—up to 10 million by some accounts—were herded out of Texas in one of the greatest migrations of animals ever known. These 19th-century cattle drives laid the foundation for Texas’ wildly successful cattle industry and helped elevate the state out of post-Civil War despair and poverty. Today, our search for an American identity often leads us back to the vision of the rugged and independent men and women of the cattle drive era. Although a number of cattle drive routes existed during this period, none captured the popular imagination like the one we know today as the Chisholm Trail. Through songs, stories, and mythical tales, the Chisholm Trail has become a vital feature of American identity. Historians have long debated aspects of the Chisholm Trail’s history, including the exact route and even its name. Although they may argue over specifics, most would agree that the decades of the cattle drives were among the most colorful periods of Texas history. The purpose of this guide is not to resolve debates, but rather to help heritage tourists explore the history and lore associated with the legendary cattle-driving route. We hope you find the historical disputes part of the intrigue, and are inspired to investigate the historic sites, museums, and attractions highlighted here to reach your own conclusions. 1835-36 The Texas Revolution 1845 The United States annexes Texas as the 28th state 1861-65 The American Civil War 1867 Joseph G. -

Hero, Non-Hero, and Anti-Hero Critical Study Of

HERO, NON-HERO, AND ANTI-HERO CRITICAL STUDY OF THE DEVELOPMENT OF CHEN JIANGONG'S FICTION By HU LINGYI THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES (Department of Asian Studies) We accept this thesis as conforming to the required standard THE UNIVERSITY OF BRITISH COLUMBIA September, 1990 0 Hu Lingyi In presenting this thesis in partial fulfilment of the requirements for an advanced degree at the University of British Columbia, I agree that the Library shall make it freely available for reference and study. I further agree that permission for extensive copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by the head of my department or by his or her representatives. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Department of The University of British Columbia Vancouver, Canada Date DE-6 (2/88) ABSTRACT This M.A. thesis is a critical study of Chen Jiangong's fiction, chiefly attempting to reveal the process of thematic development in this author's works by way of tracing the hero through non-hero to anti-hero. The first chapter, which is biographical, makes a brief account of Chen's family background, personal experience as well as the unique personality fostered by his ten year career as a coal-miner. The second chapter presents an. analysis of the thematic defects of his early fiction, and meanwhile some technical matters are succinctly introduced. The third chapter deals with the stylistic traits -- subject matter, narrative technique and language -- of the three stories which J «f t untouched in the previous chapter due to their different way of representation.