Season 2016-2017

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

San Diego Symphony Frequently Asked Questions

SAN DIEGO SYMPHONY FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS San Diego Symphony performed its first concert on December 6, 1910 in the Grand Ballroom of the then-new U.S. Grant Hotel. Now, the San Diego Symphony has grown into one of the top orchestras in the country both artistically and financially. With a current budget of $20 million, the San Diego Sym- phony is now placed in the Tier 1 category as ranked by the League of American Orchestras. The San Diego Symphony owes a deep debt of gratitude to Joan and Irwin Jacobs for their extraordinary generosity, kindness and friendship. Their support and vision has overwhelmingly contributed to making the San Diego Symphony a leading force in San Diego’s arts and cultural community and a source of continuing civic pride for all San Diegans. Artistic Q. How many musicians are there in the San Diego Symphony? A. There are 82 full-time, contracted San Diego Symphony musicians. However, depending on the particular piece of music being performed, you may see more musicians on stage. These musicians are also auditioned and hired on a case-by-case basis. You may also see fewer musicians if the particular piece of music calls for less than the full complement. Q. How are the musicians selected? A. Musicians are selected through a rigorous audition process which is comprised of an orchestra committee and the music director. Open positions are rare. When an audition is held, it is common to have 100 to 150 musicians competing for the open position. Q. Where have the musicians received their training? A. -

Apr-May 1980

MODERN DRUMMER VOL. 4 NO. 2 FEATURES: NEIL PEART As one of rock's most popular drummers, Neil Peart of Rush seriously reflects on his art in this exclusive interview. With a refreshing, no-nonsense attitude. Peart speaks of the experi- ences that led him to Rush and how a respect formed between the band members that is rarely achieved. Peart also affirms his belief that music must not be compromised for financial gain, and has followed that path throughout his career. 12 PAUL MOTIAN Jazz modernist Paul Motian has had a varied career, from his days with the Bill Evans Trio to Arlo Guthrie. Motian asserts that to fully appreciate the art of drumming, one must study the great masters of the past and learn from them. 16 FRED BEGUN Another facet of drumming is explored in this interview with Fred Begun, timpanist with the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, D.C. Begun discusses his approach to classical music and the influences of his mentor, Saul Goodman. 20 INSIDE REMO 24 RESULTS OF SLINGERLAND/LOUIE BELLSON CONTEST 28 COLUMNS: EDITOR'S OVERVIEW 3 TEACHERS FORUM READERS PLATFORM 4 Teaching Jazz Drumming by Charley Perry 42 ASK A PRO 6 IT'S QUESTIONABLE 8 THE CLUB SCENE The Art of Entertainment ROCK PERSPECTIVES by Rick Van Horn 48 Odd Rock by David Garibaldi 32 STRICTLY TECHNIQUE The Technically Proficient Player JAZZ DRUMMERS WORKSHOP Double Time Coordination by Paul Meyer 50 by Ed Soph 34 CONCEPTS ELECTRONIC INSIGHTS Drums and Drummers: An Impression Simple Percussion Modifications by Rich Baccaro 52 by David Ernst 38 DRUM MARKET 54 SHOW AND STUDIO INDUSTRY HAPPENINGS 70 A New Approach Towards Improving Your Reading by Danny Pucillo 40 JUST DRUMS 71 STAFF: EDITOR-IN-CHIEF: Ronald Spagnardi FEATURES EDITOR: Karen Larcombe ASSOCIATE EDITORS: Mark Hurley Paul Uldrich MANAGING EDITOR: Michael Cramer ART DIRECTOR: Tom Mandrake The feature section of this issue represents a wide spectrum of modern percussion with our three lead interview subjects: Rush's Neil Peart; PRODUCTION MANAGER: Roger Elliston jazz drummer Paul Motian and timpanist Fred Begun. -

LIVE from LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 P.M. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert

LIVE FROM LINCOLN CENTER December 31, 2002, 8:00 p.m. on PBS New York Philharmonic All-Gershwin New Year's Eve Concert Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East.Lorin Maazel, an icon among present-day conductors, will make his long anticipated Live From Lincoln Center debut conducting the New York Philharmonic’s gala New Year’s Eve concert on Tuesday evening, December 31. Maazel began his tenure as the Philharmonic’s new Music Director in September, and already has put his stamp of authority on the playing of the orchestra. Indeed he and the Philharmonic were rapturously received wherever they performed on a recent tour of the Far East. Celebrating the New Year with music is nothing new for Maazel: he holds the modern record for most appearances as conductor of the celebrated New Year’s Day concerts in Vienna by the Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra. There, of course, the fare is made up mostly of music by the waltzing Johann Strauss family, father and sons. For his New Year’s Eve concert with the New York Philharmonic Maazel has chosen quintessentially American music by the composer considered by many to be America’s closest equivalent to the Strausses, George Gershwin. -

Jazz Arts Program Student 2019-2020

JAZZ ARTS PROGRAM STUDENT 2019-2020 TABLE OF CONTENTS Welcome/Introduction 3 Applied Lessons 4 Your Teacher 4 Change of Teacher 4 Dividing Lessons Between Two Teachers 4 Professional Leave 5 Attendance Policy 5 Playing-related Pain 5 Ensemble and Audition Requirements 6 Juries 7 Jury for Non-graduating Students 7 Advanced Standing Jury 7 Jury Requirements for Performance Majors 8 Jury Requirements for Composition Majors 9 Comments 9 Grading 9 Postponement 9 Recitals 10 Scheduling Recitals 10 Non-required Recitals 10 Required Recitals - Undergraduate and Graduate 10 Recording of Recitals 11 Department Policies 12 Attendance 12 Subs 12 Attire 12 Grading System 13 Equipment 13 Jazz Arts Program Communications: E-mail, 13 Student Website Faculty/Student Conferences 14 Contacting the Jazz Arts Program Staff 14 Repertoire Lists 15 2 WELCOME/INTRODUCTION Dear Students, Welcome to the MSM family! We are a community of artists, educators and dreamers located in the thriving mecca and birthplace of modern jazz, Harlem, NY. This is the beginning of a journey that will undoubtedly have a major impact on the rest of your lives. As a former student, I spent the most important and transformative years of my artistic life at MSM. It was during my time here that I acquired the musical skills necessary to articulate my story in organized sound. The success of our MSM family is predicated upon three fundamental core values: Love ( empathy), Trust and Respect Jazz is an art form born from a desire to authentically express one’s individuality. Inherent in its construct is a deep understanding and appreciation for the value of an inclusive culture rich in diverse perspectives. -

2021 Band Handbook

Lincoln East Band Program 2021-2022 Policies & Procedures Handbook Mr. Tom Thorpe, Director [email protected] Ms. Nicole Shively, Assistant Director [email protected] Mr. Danny Layher, Assistant Director [email protected] Mrs. Jessica Riley, Color Guard Coordinator [email protected] 1 The Band Program Students at Lincoln East are very fortunate to have a wide variety of quality music ensemble opportunities. Below is a brief summary of each group and its role in the East Band Program. These ensembles can be subdivided into two major groups: Co-Curricular and Extra-Curricular. Co-curricular ensembles are classes that meet during the school day and you must be enrolled through Lincoln East to participate. You receive a grade for these ensembles and therefore must adhere to the grading requirements set forth by each class. Co-curricular classes often have outside-of-school time requirements at which students may be counted tardy, absent, or truant just as with any other class. Extra-Curricular ensembles are not classes. They typically meet outside the school day and in no way are required to be in Band at East. They are meant to be extra opportunities that are open to East Band students. Extra-curricular ensembles do not receive grades but may have an attendance policy, depending on the ensemble. You must be enrolled in Band class to participate in extra-curricular ensembles. CO-CURRICULAR ENSEMBLES 10th-12th Grade Marching Band This is the first quarter portion of Band at East for sophomores, juniors, and seniors. Students will be expected to attend a camp in the summer. -

The Trumpet As a Voice of Americana in the Americanist Music of Gershwin, Copland, and Bernstein

THE TRUMPET AS A VOICE OF AMERICANA IN THE AMERICANIST MUSIC OF GERSHWIN, COPLAND, AND BERNSTEIN DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Amanda Kriska Bekeny, M.M. * * * * * The Ohio State University 2005 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor Timothy Leasure, Adviser Professor Charles Waddell _________________________ Dr. Margarita Ophee-Mazo Adviser School of Music ABSTRACT The turn of the century in American music was marked by a surge of composers writing music depicting an “American” character, via illustration of American scenes and reflections on Americans’ activities. In an effort to set American music apart from the mature and established European styles, American composers of the twentieth century wrote distinctive music reflecting the unique culture of their country. In particular, the trumpet is a prominent voice in this music. The purpose of this study is to identify the significance of the trumpet in the music of three renowned twentieth-century American composers. This document examines the “compositional” and “conceptual” Americanisms present in the music of George Gershwin, Aaron Copland, and Leonard Bernstein, focusing on the use of the trumpet as a voice depicting the compositional Americanisms of each composer. The versatility of its timbre allows the trumpet to stand out in a variety of contexts: it is heroic during lyrical, expressive passages; brilliant during festive, celebratory sections; and rhythmic during percussive statements. In addition, it is a lead jazz voice in much of this music. As a dominant voice in a variety of instances, the trumpet expresses the American character of each composer’s music. -

1 Slide Per Page

Man from Mars Module 5 of Music: Under the Hood John Hooker Carnegie Mellon University Osher Course September 2018 1 Outline • Biography of George Gershwin • Analysis of Love Is Here to Stay 2 Biography • George Gershwin, 1898-1937 – Born in Brooklyn as Jacob Gershwine (Gershowitz). • Son of Russian-Jewish immigrants. – Began playing piano purchased for brother Ira – Much later, had 10-year relationship with Kay Swift, also an excellent composer. – Died from brain tumor, age 38. George and Ira 3 Biography • Musical career – Studied piano and European classical music, beginning at age 11. – Wrote songs for Tin Pan Alley, beginning age 15. – Moved to Paris to study with Nadia Boulanger • She said he didn’t need her instruction. – Wanted to study with Igor Stravinsky • Stravinsky asked, “How much money do you make a year?” On hearing the answer, he said, “Perhaps I should study with you, Mr. Gershwin.” 4 Biography • Musical career – Band leader Paul Whiteman asked Gershwin to write a piece that would improve the respectability of jazz. • He promised to do so, but forgot about it. • When he saw his piece advertised, he hurriedly wrote something – Rhapsody in Blue. 5 Biography • Musical career – Played and composed constantly. • Annoyed fellow musicians by hogging the piano. – Became known for highly original style • “Man from Mars” musically. • Example: Three Preludes (2nd at 1:22) • Perhaps result of effort to adjust European training to jazz and blues. 6 Biography • Famous compositions – Rhapsody in Blue (1924), for piano and orchestra -

The Enduring Art of Ella Fitzgerald's Most Ambitious Album

MASTERPIECE The Enduring Art of Ella Fitzgerald’s Most Ambitious Album ‘Ella Fitzgerald Sings the George and Ira Gershwin Song Books,’ which was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame at the end of January, remains a matchless treasure. By John Edward Hasse Published originally in The Wall Street Journal, Feb. 5, 2019 Nothing did more to crystallize the idea of the Great American Songbook than a series of recordings Fitzgerald made between 1956 and 1964. By showcasing eight different songwriters and songwriting teams, these albums esteemed each writer’s output as a body of work, canonized many of the songs, and raised respect for the repertory. The most celebrated of these albums, Ella Fitzgerald Sings the George and Ira Gershwin Song Books, unprecedented in scope, offers 59 tracks, more than three hours, broadly exploring one of America’s foremost song catalogs. It was recorded between January and August 1959 and issued originally in a lavish six-disc set. And with the Grammy’s this week, it’s worth reconsidering one of the singular recordings of the 20th century, which itself was inducted into the Grammy Hall of Fame at the end of January. The album resulted from a kind of collaboration among four living figures and one deceased, playing five different roles. George Gershwin, who died prematurely in 1937, composed the music, rich with jazzy, bluesy, Jewish and classical influences. His brother Ira matched George’s melodies with witty, memorable words that reveled in American vernacular speech. For the album, Ira wrote some new lyrics. The other three collaborators were each at their creative peak. -

Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding Also Provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 381 839 CS 508 906 AUTHOR Carr, John C. TITLE "Crazy for You." Spotlight on Theater Notes. INSTITUTION John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts, Washington, D.C. SPONS AGENCY Department of Education, Washington, DC. PUB DATE [95] NOTE 17p.; Produced by the Performance Plus Program, Kennedy Center Education Department. Funding also provided by the Kennedy Center Corporate Fund. For other guides in this series, see CS 508 902-905. PUB TYPE Guides General (050) EDRS PRTCE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Acting; *Cultural Enrichment; *Drama; Higher Education; Playwriting; Popular Culture; Production Techniques; Secondary Education IDENTIFIERS *Crazy for You; Historical Background; Musicals ABSTRACT This booklet presents a variety of materials concerning the musical play "Crazy for You," a recasting of the 1930 hit. "Girl Crazy." After a brief historical introduction to the musical play. the booklet presents biographical information on composers George and Ira Gershwin, the book writer, the director, the star choreographer, various actors in the production, the designers, and the musical director. The booklet also offers a quiz about plays. and a 7-item list of additional readings. (RS) ....... ; Reproductions supplied by EDRS ore the best that can he made from the original document, U S DEPARTMENT OF EDUCATION Ofi.co ofEaucabonni Research aria improvement EDUCATIONAL RESOURCES INFORMATION CENTER IERIC1 Et This document has been reproduced as received from the person or organization onqinallnq d 0 Minor charms have been made to improve reproduction quality. Points or view or opinions stated in this document do not necessarily represent official OERI position or policy -1411.1tn, *.,3^ ..*. -

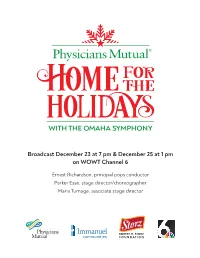

Broadcast December 23 at 7 Pm & December 25 at 1 Pm on WOWT Channel 6

Broadcast December 23 at 7 pm & December 25 at 1 pm on WOWT Channel 6 Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor Parker Esse, stage director/choreographer Maria Turnage, associate stage director ROBERT H. STORZ FOUNDATION PROGRAM The Most Wonderful Time of the Year/ Jingle Bells JAMES LORD PIERPONT/ARR. ELLIOTT Christmas Waltz VARIOUS/ARR. KESSLER Happy Holiday - The Holiday Season IRVING BERLIN/ARR. WHITFIELD Joy to the World TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Mother Ginger (La mère Gigogne et Danse russe Trepak from Suite No. 1, les polichinelles) from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY from Nutcracker PIOTR ILYICH TCHAIKOVSKY We Are the Very Model of a God Bless Us Everyone from Modern Christmas Shopping Pair A Christmas Carol from Pirates of Penzance ALAN SILVESTRI/ARR. ROSS ARTHUR SULLIVAN/LYRICS BY RICHARDSON Silent Night My Favorite Things from FRANZ GRUBER/ARR. RICHARDSON The Sound of Music RICHARD RODGERS/ARR. WHITFIELD Snow/Jingle Bells IRVING BERLIN/ARR. BARKER O Holy Night ADOLPH-CHARLES ADAM/ARR. RICHARDSON Let It Snow, Let It Snow, Let It Snow JULE STYNE/ARR. SEBESKY We Need a Little Christmas JERRY HERMAN/ARR. WENDEL Frosty the Snowman WALTER ROLLINS/ARR. KATSAROS Hark All Ye Shepherds TRADITIONAL/ARR. RICHARDSON Sleigh Ride LEROY ANDERSON 2 ARTISTIC DIRECTION Ernest Richardson, principal pops conductor and resident conductor of the Omaha Symphony, is the artistic leader of the orchestra’s annual Christmas Celebration production and internationally performed “Only in Omaha” productions, and he leads the successful Symphony Pops, Symphony Rocks, and Movies Series. Since 1993, he has led in the development of the Omaha Symphony’s innovative education and community engagement programs. -

The Great American Songbook Through the Lens of Judy Garland

The Great American Songbook Through the Lens of Judy Garland An Honors Thesis (MUSP 401) By Lindsey Stamper Thesis Advisor Dr. Jon Truitt Ball State University Muncie, Indiana December 2017 Expected Date of Graduation May 2018 0JpCo)} U ndc r.::J r c, a I he c 1 d. i'("; . ._ tJ c ( JP, Abstract r} ,..J... This thesis paper, as well as·the accompanying recital, delves into the topic of The Great American Songbook Through the Lens of Judy Garland. The Great American Songbook is a collection of American standard repertoire from the late nineteenth century to the middle of the twentieth. Judy Garland in particular is an exemplary performer of this period; her life parallels the troubles and careers of many other performers in this era. By exploring and performing songs that Garland performed during her career, this paper relates the history of American music to the life of the acclaimed Judy Garland. Acknowledgments I would like to thank Dr. Jon Truitt for the guidance, insight, advice, and training he has provided me with throughout this project and these past four years. His help with the many performance endeavors of my collegiate career has been invaluable. I would also like to thank my mom and dad for inspiring a curiosity and interest in music at a young age. Lastly, thank you to Julian for always listening with kind and encouraging ears. Process Analysis Statement Recitals, concerts, and cabarets are important events in a music educator's profession. These are the culmination of unseen efforts rehearsing music, planning logistics, and organizing personnel. -

Gershwin Part 1: “I Got Rhythm” Music from 9AM – 9:30 - Log On, Get Your Coffee, Listen, Relax

Gershwin Part 1: “I Got Rhythm” Music from 9AM – 9:30 - Log on, get your coffee, listen, relax. • “I Got a Crush on You” recorded by Nat Adderley in 1960 on Work Song. Written in 1928 for Treasure Girl. • “Nice Work If You Can Get It” recorded by Sarah Vaughn in 1950 on Sarah Vaughn with George Treadwell and his All Stars. Written in 1937 for Damsels in Distress. • “Isn’t It A Pity” recorded by Cheryl Bentyne in 2010 on The Gershwin Songbook. Written in 1933 for Pardon My English. • “I Loves You, Porgy” recorded by Billie Holiday, accompanied by Bobby Tucker. Written in 1935 for Porgy & Bess. • “Let’s Call The Whole Thing Off” recorded by Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong with the Oscar Peterson Trio in 1957 on Ella and Louis Again. Written in 1937 for Shall We Dance. • “They Can’t Take That Away From Me” recorded by Frank Sinatra in 1962 on Sinatra and Swingin’ Brass. Written in 1937 for Shall We Dance. • “Do It Again” recorded by Beverly Kenney accompanied by Ellis Larkins in 1958 on Beverly Kenney Sings for Playboys. Written in 1922 for The French Doll. • “Love is Here to Stay” recorded in 1955 by Carmen McRae. Written in 1937 for The Goldwyn Follies. • “My One and Only” recorded in 1950 by Ella Fitzgerald with Ellis Larkin on Ella Sings Gershwin. Written in 1927 for Funny Face. • “I Got Rhythm” recorded in 1964 in Sweden by Sarah Vaughn. Written in 1930 for Girl Crazy. Class Begins at 930AM The Gershwins Part 1: “I Got Rhythm” Course Agenda showing the music 1.