Accountability and Transparency; Annexes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recorder 298.Pages

RECORDER RecorderOfficial newsletter of the Melbourne Labour History Society (ISSN 0155-8722) Issue No. 298—July 2020 • From Sicily to St Lucia (Review), Ken Mansell, pp. 9-10 IN THIS EDITION: • Oil under Troubled Water (Review), by Michael Leach, pp. 10-11 • Extreme and Dangerous (Review), by Phillip Deery, p. 1 • The Yalta Conference (Review), by Laurence W Maher, pp. 11-12 • The Fatal Lure of Politics (Review), Verity Burgmann, p. 2 • The Boys Who Said NO!, p. 12 • Becoming John Curtin and James Scullin (Review), by Nick Dyrenfurth, pp. 3-4 • NIBS Online, p. 12 • Dorothy Day in Australia, p. 4 • Union Education History Project, by Max Ogden, p. 12 • Tribute to Jack Mundey, by Verity Burgmann, pp. 5-6 • Graham Berry, Democratic Adventurer, p. 12 • Vale Jack Mundey, by Brian Smiddy, p. 7 • Tribune Photographs Online, p. 12 • Batman By-Election, 1962, by Carolyn Allan Smart & Lyle Allan, pp. 7-8 • Melbourne Branch Contacts, p. 12 • Without Bosses (Review), by Brendan McGloin, p. 8 Extreme and Dangerous: The Curious Case of Dr Ian Macdonald Phillip Deery His case parallels that of another medical doctor, Paul Reuben James, who was dismissed by the Department of Although there are numerous memoirs of British and Repatriation in 1950 for opposing the Communist Party American communists written by their children, Dissolution Bill. James was attached to the Reserve Australian communists have attracted far fewer Officers of Command and, to the consternation of ASIO, accounts. We have Ric Throssell’s Wild Weeds and would most certainly have been mobilised for active Wildflowers: The Life and Letters of Katherine Susannah military service were World War III to eventuate, as Pritchard, Roger Milliss’ Serpent’s Tooth, Mark Aarons’ many believed. -

RCOA Annual Report 2010-2011 Size

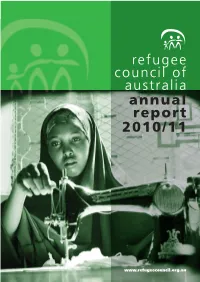

refugee council of australia annual report 2010/11 www.refugeecouncil.org.au Front cover: Ayan, 16, is one of more than 60,000 people who have fled war- Acknowledgements torn south-central Somalia for Galkayo, in Somalia's Puntland region. Her goal is The Refugee Council of Australia would like to acknowledge the generous to teach the sewing skills that she has support of the following organisations and individuals for the work of the learned to other displaced girls from Council during 2010-11: poor families so they can provide for Funding support: In-kind support: their families. © UNHCR / R.Gangale • AMES Victoria • Majak Daw • Amnesty International Australia • Friends of STARTTS • Australian Cultural Orientation • Yalda Hakim Program, IOM • Carina Hoang • Australian Refugee Foundation • Host 1 Pty Ltd • City of Sydney • Gracia Ngoy • Department of Immigration and • Pitt Street Uniting Church Citizenship • Nicholas Poynder • Leichhardt Council • Timothy Seeto • McKinnon Family Foundation • Shaun Tan • Navitas • UNHCR Regional Office, Canberra • NSW AMES • University of NSW • NSW Community Relations Commission • Najeeba Wazefadost Sections • SBS • Webcity • Victorian Multicultural Commission President’s report 1 RCOA’s objectives 2 and priorities RCOA’s people 4 Refugee settlement policy 5 Asylum policy 8 International links 11 Information and 14 community education Our organisation 15 RCOA members 16 Financial report 20 President’s Report he 2010-11 financial year proved to be one of the most In the public discussion of refugee policy, in our submissions challenging and difficult for national refugee policy, in the and statements and in our private discussions with the T30-year history of the Refugee Council of Australia (RCOA). -

Appendix Mr Bernard Collaery

Appendix Mr Bernard Collaery Pursuant to Resolution 5(7)(b) of the Senate of 25 February 1988 Reply to statement by Senator the Hon George Brandis (4 December 2013) 1. Pursuant to Senate Privilege Resolution 5 of 25 February 1988, I request that you refer this statement to the Senate Standing Committee of Privileges, and that it be published in the Parliamentary record as a response to a statement of Senator Brandis of 4 December 2013. 2. Senator Brandis’ statement of 4 December 2013 was as follows (Hansard, pp 819–820): Yesterday, search warrants were executed at premises in Canberra by officers of the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) and, in the course of the execution of those warrants, documents and electronic data were taken into possession . The premises were those of Mr Bernard Collaery and a former ASIS officer. The names of ASIS officers–whether serving or past– may not be disclosed. The warrants were issued by me, at the request of ASIO, on the grounds that the documents and electronic data in question contained intelligence relating to security matters. By section 39 of the Intelligence Services Act 2001, it is a criminal offence for a current or former officer of ASIS to communicate ‘any information or matter that was prepared by or on behalf of ASIS in connection with its functions or relates to the performance by ASIS of its functions’, where the information has come into his possession by reason of his being or having been an officer of ASIS. … Last night, rather wild and injudicious claims were made by Mr Collaery and, disappointingly, by Father Frank Brennan, that the 4 purpose for which the search warrants were issued was to somehow impede or subvert the arbitration. -

Chapter 3 CLA 180303

Chapter 3 – Civil Liberties Australia Expanding freedom from the centre outwards As faster transport and near-instant communications began to overcome the “tyranny of distance” of Australia in the late-20th century, civil liberties in general was not moving far, or fast. In the Australian Capital Territory, a civil liberties group operated for 30 years from 4 June 1969. But as power centralised in the federal parliament, civil liberties in Canberra was down to its last person standing. The Council of Civil Liberties of the ACT formally died at the end of 2001, when the Registrar of Incorporated Associations cancelled its incorporation because the group had not lodged annual returns for three years. When the authors became aware in mid-2001 of the probable de- registration, they sought advice from then- ACT Chief Justice Terry Higgins (photo, with CLA President Dr Kristine Klugman), and were directed to Laurie O’Sullivan, a retired barrister who had run the organisation for all but the last five years of its existence. He bitterly related the tale of the ACT CCL’s death (see ACT Chapter). A nation’s capital obviously should have an active civil liberties watchdog, so the authors decided to incorporate a new body. To ensure it began life free of past political baggage (see ACT chapter), the name chosen was Civil Liberties Australia (ACT) Inc. As CLA was being born in the latter half of 2001, western life and liberty was collapsing. No-one knew when two aircraft crashed into New York’s Twin Towers (on ‘9/ll', or 11 September 2001) by how much or for how long. -

Act Law Society Annual Report 2019-20 Law Society of the Australian Capital Territory

ACT LAW SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 LAW SOCIETY OF THE AUSTRALIAN CAPITAL TERRITORY ABN 60 181 327 029 Level 4, 1 Farrell Place, Canberra City ACT 2601 PO Box 1562, Canberra ACT 2601 | DX 5623 Canberra Phone (02) 6274 0300 | [email protected] www.actlawsociety.asn.au Executive President Chris Donohue Vice Presidents Elizabeth Carroll Peter Cain Secretary George Marques Treasurer Sama Kahn Council-appointed Member Mark Tigwell Immediate Past President Sarah Avery Councillors Radmila Andric Rahul Bedi Farzana Choudhury Timothy Dingwall Alan Hill Gavin Lee Sage Leslie Susan Platis Mark Tigwell Angus Tye Staff Chief Executive Officer Simone Carton Professional Standards Manager Rob Reis Finance & Business Services Manager Lea McLean Executive Secretary Nicole Crossley Professional Standards Committee Secretary Linda Mackay Research Officer Tien Pham Professional Development Officer Carissa Webster Communications Officer Nicole Karman Committee Administrator Tanya Holt Bookkeeper Kathleen Lui Receptionist & LAB Administrator Robyn Guilfoyle Administration Support Janette Graham Leonnie Borzecki © This publication is copyright and no part of it may be reproduced without the consent of the Law Society of the Australian Capital Territory. The Law Society acknowledges the Ngunnawal and Ngambri peoples, who are the traditional custodians of the land on which our building is located. ii ACT LAW SOCIETY ANNUAL REPORT 2019-20 PRESIDENT’S REPORT CEO’S REPORT CORPORATE OVERVIEW Role of the Law Society ......................................................................................8 -

Witness K, Bernard Collaery Could Have Hearings Split, Court Hears

Witness K, Bernard Collaery could have hearings split, court hears https://www.canberratimes.com.au/story/6300134/former-spy-witness-k-and-his-lawyer-could-face- split-hearings-court-hears/?cs=14264 Alexandra Back – The Canberra Times – 30 July 2019 The case of a former spy and his lawyer who exposed an Australian bugging operation against the tiny nation of East Timor could be split and heard in two separate jurisdictions, a court has heard. The spy known only as Witness K and his lawyer Bernard Collaery are accused of conspiring to breach intelligence laws by revealing information about Australia's secret intelligence service. They plan to defend the allegations. Ken Archer, the barrister for Mr Collaery, told the ACT Magistrates Court on Tuesday that his client had a firm view about how he wanted the case to proceed, and that was by indictment and committal to the ACT Supreme Court. The prosecution has consented to that course. That would mean the preliminary hearing to determine national security orders listed for next week would be unnecessary, Mr Archer said, and it could instead be relisted in the higher court at a later date. However, in a parting that could see the two cases heard separately, Robert Richter QC, the barrister appearing for Witness K, said it was "desired" that his client's matter remain in the summary jurisdiction of the ACT Magistrates Court and that the question may soon be resolved with prosecutors by consent. Mr Richter also said they were hopeful of coming to an agreement with the Commonwealth on a set of agreed national security orders. -

Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube

THE ARTS This PDF document was made available CHILD POLICY from www.rand.org as a public service of CIVIL JUSTICE the RAND Corporation. EDUCATION ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT Jump down to document6 HEALTH AND HEALTH CARE INTERNATIONAL AFFAIRS The RAND Corporation is a nonprofit NATIONAL SECURITY research organization providing POPULATION AND AGING PUBLIC SAFETY objective analysis and effective SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY solutions that address the challenges SUBSTANCE ABUSE facing the public and private sectors TERRORISM AND HOMELAND SECURITY around the world. TRANSPORTATION AND INFRASTRUCTURE WORKFORCE AND WORKPLACE Support RAND Purchase this document Browse Books & Publications Make a charitable contribution For More Information Visit RAND at www.rand.org Explore RAND National Defense Research Institute View document details Limited Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law as indicated in a notice appearing later in this work. This electronic representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for non- commercial use only. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of our research documents. This product is part of the RAND Corporation monograph series. RAND monographs present major research findings that address the challenges facing the public and private sectors. All RAND mono- graphs undergo rigorous peer review to ensure high standards for research quality and objectivity. Counterinsurgency in a Test Tube Analyzing the Success of the Regional Assistance Mission to Solomon Islands (RAMSI) Russell W. Glenn Prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command Approved for public release; distribution unlimited NATIONAL DEFENSE RESEARCH INSTITUTE The research described in this report was prepared for the United States Joint Forces Command. -

10 MAY 2019 Friday, 10 May 2019

NINTH ASSEMBLY 10 MAY 2019 www.hansard.act.gov.au Friday, 10 May 2019 Distinguished visitors ............................................................................................... 1507 Visitors ..................................................................................................................... 1508 Self-government in the territory—30th anniversary ................................................ 1508 Mark of reconciliation—gift of possum skin cloak (Statement by Speaker) ........... 1522 Adjournment ............................................................................................................ 1522 Legislative Assembly for the ACT Friday, 10 May 2019 MADAM SPEAKER (Ms J Burch) took the chair at 10 am, made a formal recognition that the Assembly was meeting on the lands of the traditional custodians, and asked members to stand in silence and pray or reflect on their responsibilities to the people of the Australian Capital Territory. Distinguished visitors MADAM SPEAKER: Members, before I call the Chief Minister I would like to acknowledge the presence in the gallery of a number of former members. I would like to acknowledge: Chris Bourke Bernard Collaery Helen Watchirs, representing the late Terry Connolly Greg Cornwell AO Rosemary Follett AO Ellnor Grassby Harold Hird OAM Lucy Horodny Gary Humphries AO Dorothy and son Kevin Jeffery, representing the late Val Jeffery Norm Jensen Sandy Kaine, representing the late Trevor Kaine Louise Littlewood Karin MacDonald Roberta McRae OAM Michael Moore AM Richard Mulcahy Paul Osborne Mary Porter AM David Prowse Marion Reilly Dave Rugendyke Brendan Smyth 1507 10 May 2019 Legislative Assembly for the ACT Bill Stefaniak AM Helen Szuty Andrew Whitecross Bill Wood On behalf of all members, I extend a warm welcome to you. I welcome all former members joining us in this quite significant celebration. Visitors MADAM SPEAKER: I would also like to acknowledge the two former clerks, Don Piper and Mark McRae. -

Legal Tweaks That Would Change NSW and the Nation

Legal Tweaks that would change NSW and the nation. 2018 Edited By Janai Tabbernor, Elise Delpiano and Blake Osmond Published By New South Wales Society of Labor Lawyers Artistic Design By Lewis Hamilton Cover Design By Laura Mowat Our Mission The New South Wales Society of Labor Lawyers aims, through scholarship and advoca- cy, to effect positive and equitable change in substantive and procedural law, the adminis- tration of justice, the legal profession, the provision of legal services and legal aid, and legal education. Copyright 2018 New South Wales Society of Labor Lawyers INC9896948. The 2018 Committee is Lewis Hamilton, Janai Tabbernor, Jade Tyrrell, Claire Pullen, Kirk McKenzie, Tom Kelly, Eliot Olivier, Rose Khalilizadeh, Philip Boncardo, Stephen Lawrence, Tina Zhou and Clara Edwards. Disclaimer Any views or opinions expressed are those of the individual authors and do not necessari- ly reflect the views and opinions of the New South Wales Society of Labor Lawyers or of the Australian Labor Party. Moreover, any organisations represented in this publication are not expressing association with the New South Wales Society of Labor Lawyers or the Australian Labor Party. Acknowledgements Our thanks goes to all those who contributed to this publication, and to the lawyers before them who built the modern Australian Labor Party and embedded social justice in our national identity. We especially thank our sponsors, Maurice Blackburn Lawyers, who carry on the inspiring legacy of Maurice McRae Blackburn, a champion lawyer and a federal Labor MP. 2 INTRODUCTIONLegal TweaksFAMILY LAW 1. Foreword - Mark Dreyfus QC MP 37. Janai Tabbernor 2. Foreword - Paul Lynch MP 38. -

01 January 2021 Clarion

CLArion Issue No 2101–01, January 2021 CLA on Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/CivilLibertiesAus/ Email newsletter of Civil Liberties Australia (A04043) Email: Secretary(at)cla.asn.au Web: http://www.cla.asn.au/ ____________________________________________ Is Australia a nation of justice? As we put 2020 vision behind us, it’s an opportunity to evaluate the ramifications of a health pandemic on rights and liberties. For example, why was emergency behaviour by governments, authorities and police more draconian in some places than others? Victoria locking down nine tower blocks without any forewarning is a case in point. The Ombudsman found it breached the state’s human rights law. https://tinyurl.com/y8kllkak How can we create better emergency laws for the future, so that people have a real right to contest decisions – in a timely fashion – that are anti-freedoms…and sometimes just plain stupid. For example, no- one has yet explained why preventing people leaving Australia to go overseas was sensible? With virtually no demand for flights out of Australia, there was no demand for flights into Australia, so making it harder for Australians to get home. The pandemic has thrown up fundamental questions about how we’re governed, and how we could improve both the governing mechanisms and governance-with-propriety in future. Certainly, 2021 will likely be a year to tackle core issues of citizenship, an Indigenous treaty, rights and responsibilities (and the issue of a human rights act), as well as the mix-and-match interactions between the authoritarian silos and ivory towers that can apparently take over society at a moment’s notice. -

The Australian Intelligence Community

Tom Nobes | The Emergence and Function of the Australian Intelligence Community The Australian Intelligence Community: Why did the AIC emerge the way it did and how well has it served the nation? TOM NOBES The Australian Intelligence Community (AIC) emerged in the Commonwealth executive branch of state throughout the 20th century, methodically reconfiguring in response to royal commission and government review recommendations. The AIC’s structure continues to be altered today in the face of ‘an increasingly complex security environment’.1 Such reconfiguration has been necessary in order to create a more effective and accountable AIC that serves the executive government by protecting Australian security and safety interests. Today, the AIC agencies work within a largely legislative framework, informed by liberal ends and values that balance individual liberty and privacy against communal security and peace.2 The AIC consists of six agencies today; the Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO), the Australian Secret Intelligence Organisation (ASIS), the Australian Signals Directorate (ASD), the Defence Intelligence Organisation (DIO), the Australian Geospatial-Intelligence Organisation (AGO) and lastly the Office of National Assessments (ONA).3 This essay will briefly outline the development of the AIC over the last 100 years, and then discuss in detail why it emerged in the way that it did. Particular emphasis will be placed on the changes that occurred as a result of the Royal Commission on Intelligence and Security (1974-1977), the Protective Security Review (1979) and the Royal Commission on Australia’s Security and Intelligence Agencies (1984). The essay will then proceed to analyse the ways in which the AIC has, and hasn’t, served the nation. -

Frontiers in International Environmental Law: Oceans

chapter 2 Water and Soil, Blood and Oil Demarcating the Frontiers of Australia, Indonesia and Timor- Leste David Dixon 1 Frontiers, Borders and Boundaries This chapter explores frontiers as political and economic constructs, focusing on the contested borders and boundaries of Timor-Leste.* At its centre is a dispute about the maritime boundary between Timor-Leste and Australia in which access to hydrocarbon resources in the Timor Sea has been at stake. In 2018, Timor- Leste and Australia signed a Treaty ‘to settle finally their mari- time boundaries in the Timor Sea’ (2018 Treaty).1 Despite considerable mutual self- congratulation,2 this treaty does not finalise the boundary (instead cre- ating an anomalous and temporary enclave to accommodate Australia’s eco- nomic interests). Nor does it deal conclusively with the crucial question of who should extract oil and gas or where processing should be carried out: it could not do so, for these decisions are ultimately not for nation states but for international corporations. To them, frontiers are less about pride and security than about opportunities and obstacles. This indicates a broader theme: bor- ders and boundaries may be products not of the rational application of legal principles, but rather of political (often symbolic) concerns about sovereignty and of pragmatic, economic interests in resources allocated to states by fron- tier delineations. * Acknowledgements: This paper is written in tribute to David Freestone, a friend and for- mer colleague who has taught me much, not least the importance of academic integrity and commitment. As well as thanking David, I acknowledge Richard Barnes, Clinton Fernandes, Patrick Earle, José Ramos-Horta and the extraordinary people at Laˊo Hamutuk and Timor- Leste’s Marine Boundary Office.