Chapter 3 Physical Restraint of Horses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Read Book Through England on a Side-Saddle Ebook, Epub

THROUGH ENGLAND ON A SIDE-SADDLE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Celia Fiennes | 96 pages | 02 Apr 2009 | Penguin Books Ltd | 9780141191072 | English | London, United Kingdom Sidesaddle - Wikipedia Ninth century depictions show a small footrest, or planchette added to the pillion. In Europe , the sidesaddle developed in part because of cultural norms which considered it unbecoming for a woman to straddle a horse while riding. This was initially conceived as a way to protect the hymen of aristocratic girls, and thus the appearance of their being virgins. However, women did ride horses and needed to be able to control their own horses, so there was a need for a saddle designed to allow control of the horse and modesty for the rider. The earliest functional "sidesaddle" was credited to Anne of Bohemia — The design made it difficult for a woman to both stay on and use the reins to control the horse, so the animal was usually led by another rider, sitting astride. The insecure design of the early sidesaddle also contributed to the popularity of the Palfrey , a smaller horse with smooth ambling gaits, as a suitable mount for women. A more practical design, developed in the 16th century, has been attributed to Catherine de' Medici. In her design, the rider sat facing forward, hooking her right leg around the pommel of the saddle with a horn added to the near side of the saddle to secure the rider's right knee. The footrest was replaced with a "slipper stirrup ", a leather-covered stirrup iron into which the rider's left foot was placed. -

Mastering Equine - Advanced Horsemanship Mastering Horses

4-H Equine Series Mastering Equine - Advanced Horsemanship Mastering Horses The purpose of the Mastering Horses project is to help you to further develop skills in all areas of equine management. By setting goals to become a responsible horse owner and a good rider, you will become strong in the areas of self-discipline, patience, responsibility, respect Table of Contents and pride in your accomplishments. Introduction 1 As you progress through the Mastering Equine manual, remember that Skill Builder 1: 3 time is not limited. Follow the 4-H motto and “Learn to do by doing”. Ground work and Although you may finish the activities in the manual quite quickly and Psychology easily, you may wish to spend more time in this unit to improve your Skill Builder 2: Grooming 19 horsemanship skills. Be sure to Dream It! record what you wish to complete this club year. Then Do It! After your lessons and at your Skill Builder 3: Identification 30 Achievement you can Dig It! and Conformation Horsemanship is an art of riding in a manner that makes it look easy. Skill Builder 4: Safety and 55 To do this, you and your horse must be a happy team and this takes Stable Management time and patience. Skill Builder 5: Health 64 The riding skills you develop in this project will prepare you for Skill Builder 6: Riding 97 advancement. Whether you are interested in specialized riding Showcase Challenge 138 disciplines or horse training, you will need to learn more about aids and equipment. Portfolio Page 140 No matter what kind of goals you set for yourself in Mastering - Revised 2019 - Horsemanship, the satisfaction you experience will come from the results of your own hard work. -

Bones of Amelia Earhart Believed Found on Saipan

> A O E T W E M T X WEDNESDAY, NOVEMBER 22, 1961 iNanrhfBtpr £itraing Hirralb : Manchester Stores Open Tonight for Christmas Shopping Until 9 o^Ctock A ^ u t Town Bupertnt«nd«nt o f Sctioola wtl> ATMBgelDail^NerPrw^ Ham H. <^rtia will apeak at an For the Week Ended orientation meeting for newly Xovember 11, 1991 elected achool board members in tbe ^ rtford . area and north cen tra] parts of the state Monday 13,487 in Windsor. The meeting in Member of the Audit scheduled to begin with a social Burenn of Circulation hour at 5 p.m. at Carville's Res taurant, a dinner at d, and the tmalnees session at Til 5. VOL. LXXXI, NO., 46 (TWENTY-EIGHT PAGES-rlN TWO SECTIONS) The Tall Cedars Band will'pro- MANCIfESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 24, 1961 (Claaalfled Advertltlng on Page, 26.) PRICE FIVE CENTS vide musical entertainment at the Five-Mile, Road Race tomorrow morning. Bandsmen are asked to report in front of the Main Barn ard School building at 9:45 ready to play at 10 o'clock. There will be no training aea- Bion for. BrOwnie leaders on Fri day at Center Congregational Bones of Amelia Earhart Church because of the Thanksgiv ing holiday. The next and last ses sion will hi on Friday. Dec. 1, at 9:30 a_m. at Center Church. lisssons for junior squu-e danc- era, sponsored by the Manchester Reneation Department, will be Believed Found on Saipan canceled this week because of the ‘thanksgiving holiday. Classes will resume Thursday, Nov. 30. -

Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams

Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams A thesis presented to the faculty of the Scripps College of Communication of Ohio University and the Institute for Communication and Media Studies of Leipzig University In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees Master of Science in Journalism (Ohio University), Master of Arts in Global Mass Communication (Leipzig University) Chris J. Vonderlind December 2019 © 2019 Chris J. Vonderlind. All Rights Reserved. This thesis titled Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams by CHRIS J. VONDERLIND has been approved for the E.W. Scripps School of Journalism, the Scripps College of Communication, and the Institute for Communication and Media Studies by Veronika Karnowski Associate Professor of the Institute for Communication and Media Studies Scott Titsworth Dean, Scripps College of Communication, Ohio University Christian Pieter Hoffman Director, Institute for Communication and Media Studies, Leipzig University ii Abstract CHRIS J. VONDERLIND, M.S., Journalism; M.A., Global Mass Communication, December 2019 3709740 Twitch TV Uncovered – Interactivity and Community in Video Game Live Streams Director of Thesis: Veronika Karnowski Committee Members: Veronika Karnowski, Jatin Srivastava, Rosanna Planer Online media is continuing to transform the media consumption habits of today’s society. It encompasses various forms of content, modes of consumption and interpersonal interactions. Live-streaming is one of the less observed but growing forms of new media content. It combines aspects of online video entertainment and user content creation such as YouTube, and social media such as Instagram, in a live setting. The goal of this thesis is to explore this phenomenon by looking at the video game streaming platform Twitch, and, more specifically, the interactions taking place during the live streams. -

Horse Manual

Original Compiled by Dr. Revision Compiled by Ann M. Swinker Extension Connie Cecil Equine Specialist 4-H Curriculum Specialist Colorado State University Extension Colorado State University Extension Acknowledgments: This revised 2018edition of the Colorado 4-H Horse Project has involved many contributors. Members of the Colorado State University Extension Horse Advisory Committee collected and revised information for use in this manual. Agents who represented their districts on this committee: Dr. Ragan Adams DVM, CSU Colorado Veterinary Extension Specialist Diane Kern Jodie Martin-Witt Scott Stinnett Jenny Leonetti Tom Sharpe Jonathan Vrabec The original Project contributors who did not participate in this revision also deserve acknowledgment for the portions of their work that have been preserved: Nicolette Ahrens Kurt Jones Al Meier Lori Rodcay Sharon Bokan Brett Kirch Kathryn Milne Bobbie Skelton Brenda Brown Gary Lancaster Bill Nobles Gary Small Russ Brown Christianne Magee Vern Nutter Jim Smith Bernie Elliott Billie Malchow Kipp Nye Dr. Kelcey Swyers Mendy Gonzales Ernie Marx Dean Oatman Dessa Watson Karen Hansen Robert Mathis Donna Pattee Tiare Wells Deb Hindi Angela Mannick Diana Quintana Todd Yeager Larry Hooker Dave McManus Janice Roberts Jodi Zeier Mark Horney Carol McNeal We wish to thank Bill Culbertson, Extension Horse Specialist Emeritus, for his contribution to the content and artwork in this manual and give him special acknowledgement. Edited by Sharon Gale, Colorado State University. Layout and design by Karen Cagle, 4-H Youth Development Program. Editorial assistance by Christina Berryman and Dr. Paul Siciliano, Animal Sciences, Colorado State University. Horse Ration Analysis worksheets by Christopher Fox. Diagrams from National4-H Horse Program. -

Title 325. Oklahoma Horse Racing Commission Chapter 60

TITLE 325. OKLAHOMA HORSE RACING COMMISSION CHAPTER 60. RUNNING THE RACE 325:60-1-6. Weighing out All Jockeys taking part in a race must shall be weighed out by the Clerk of Scales no more than one hour preceding the time designated for the race. Any overweight in excess of one pound shall be declared by the Jockey to the Clerk of Scales, who shall report such the overweight and any change in Jockeys to the Stewards for the immediate public announcement. A Jockey must shall be neat in appearance and must shall wear a conventional riding costume. A Jockey's weight shall include his/her clothing, boots, saddle and its attachments, and any other equipment except the whip, bridle, bit or reins, safety helmet, safety vest, blinkers, goggles and number cloth. A safety vest shall be worn by the Jockey and shall weigh no more than two pounds, and shall be designed to provide shock absorbing protection to the upper body of at least a rating of five as defined by the British Equestrian Trade Association (BETA). 325:60-1-9. Prohibited use of equipment Jockeys are prohibited from whipping a horse excessively, brutally, or upon the head, except when necessary to control the horse in an emergency. No mechanical or electrical devices or appliances other than the ordinary whip or approved twitch shall be possessed by any person or used on any horse at any time, whether in a race or otherwise. (a) A jockey shall only use a riding crop in a manner consistent with exerting his/her best efforts to obtain a maximum placing that affects purse distribution or wagering pools. -

Iowa Ffa Horse Evaluation and Selection

HORSE EVALUATION Career Development Event This is a Skills CDE Table of Contents Section Page General Skills Career Development Event Rules ....................................................2 Overview ..................................................................................................................4 AFNR Content Standards ........................................................................................4 Event Rules ..............................................................................................................5 Event Rules for Middle School Teams ....................................................................5 Event Format ............................................................................................................5 Event Resources .......................................................................................................7 Scoring and Ranking of Teams and Individuals ......................................................7 Awards .....................................................................................................................8 Event Materials ........................................................................................................8 1055 SW Prairie Trail Pkwy Ankeny, IA 50023 P: 515-965-7376 F: 515-965-7373 iowaffa.com AG SKILLS CAREER DEVELOPMENT EVENT GENERAL POLICIES, RULES, RESULTS AND STANDARDS *Violations of any of the following rules may be grounds for the disqualification of the participants. I. Board Policies The following -

When All You Have Is a Banhammer: the Social and Communicative Work of Volunteer Moderators Claudia Lo

When All You Have is a Banhammer: The Social and Communicative Work of Volunteer Moderators by Claudia Lo B.A., Swarthmore College (2016) Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies at the MASSACHUSETTS INSTITUTE OF TECHNOLOGY June 2018 © Claudia Lo, MMXVIII. All rights reserved. The author hereby grants to MIT permission to reproduce and to distribute publicly paper and electronic copies of this thesis document in whole or in part in any medium now known or hereafter created. Author............................................................. Department of Comparative Media Studies May 11, 2018 Certifiedby......................................................... T. L. Taylor Professor of Comparative Media Studies Thesis Supervisor Acceptedby......................................................... Heather Hendershot Professor of Comparative Media Studies, Director of Graduate Studies 2 When All You Have is a Banhammer: The Social and Communicative Work of Volunteer Moderators by Claudia Lo Submitted to the Department of Comparative Media Studies on May 11, 2018, in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Comparative Media Studies Abstract The popular understanding of moderation online is that moderation is inherently reactive, where moderators see and then react to content generated by users, typically by removing it; in order to understand the work already being performed by moderators, we need to expand our understanding of what that work entails. Drawing upon interviews, participant obser- vation, and my own experiences as a volunteer community moderator on Reddit, I propose that a significant portion of work performed by volunteer moderators is social and com- municative in nature. -

Question # Question Answer Source ROUND 1 One-1 What Are Two

Question # Question Answer Source ROUND 1 One-1 What are two principle innate methods of self- Flight or fight. protection utilized by horses? HIH, 320-1 Two-2 What is a common name for a conditioned stimulus? a cue HIH 1240 page 1 Three-3 Where are hooks on teeth found? on the first upper cheek teeth (premolar) and last bottom cheek teeth (molar) HIH 405 Four-4 What breed of horse is described as a Warmblood combination of any breeds that are not 100% hot- blood or 100% cold-blood? HIH 151B-1 Five-1 Other than salt, identify two other minerals that Manganese, iron, cobalt, would be found in trace mineralized salt. copper, iodine or zinc YLM ADV 302-2L Six-2 Your horse sustained a laceration and has bright Direct pressure to the wound red blood spurting from the wound. What would be your initial action to control the bleeding? HIH 440-2 Seven-3 For what maximum period of time after parturition up to 12-36 hours after birth HIH 950-3 would the foal be able to absorb the (accept anything within this immunoglobulins in colostrum? range) Eight-4 How do you measure the size of an English saddle? From the saddle nail to the mid- HIH 1100-3 point of the cantle 9 What breed was formerly known as the “Karster” Lipizzan (Lipizzaner) horse? HIH 159B-2 10 What highly contagious organism is responsible Rotavirus HIH 950-7 for approximately 90% of all foal diarrhea outbreaks? 11-Toss Up What type of inheritance affects males and Autosomal recessive females equally and results in an observed phenotype only when there are two copies of the recessive allele -

HORSE EXPO STUDY GUIDE Madera County 4-H Horse Level I & II HORSE EXPO STUDY GUIDE Madera County 4-H Level I & II

HORSE EXPO STUDY GUIDE Madera County 4-H Horse Level I & II HORSE EXPO STUDY GUIDE Madera County 4-H Level I & II Written Test Level I Level II Entry Form 22 28 Quiz Matching 15 15 Quiz Multiple Choice 15 10 Quiz True/False 5 Parts 20 33 Western Saddle 10 18 English Saddle 5 10 Bridles - English & Western 6/5 Sub-Total for Written Test 103 114 Expo Day Skills Level I Level II Feed ID 5 10 Equipment ID 15 20 Pre-Riding Skills 60 Vet Skills 60 Riding Skills 40 Showmanship Skills 25 30 Judging 10/10 10/10 Sub-Total for Skills Portion 125 180 Sub-Total for Written Test 103 114 Total for Expo Skills 228 294 Total Needed to Pass Level 182.4 235.2 Madera County Horse Expo 8/06 -1- PLEASE PRINT OR TYPE LEVEL I & II ___________________________________________________ HORSE ENTRY FORM ______ __________ ______ LAST NAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE INITIAL JUNIOR DEPARTMENT GRADE BIRTH DATE AGE ___________________________________________________ ALL DIVISIONS ADDRESS MADERA DISTRICT FAIR ________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ 25826 AVE. 15 ½ SIGNATURE OF LEGAL PARENT OR GUARDIAN CITY ZIPCODE PHONE MADERA, CA 93639 ___________________________________________________ 674-8511 SIGNATURE OF OWNER OR AGENT DATE _____________________________ DIVISION CLASS # CLASS DESCRIPTION NAME OF HORSE ENTRY FEE TOTAL FEE 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 CONSULT PREMIUM BOOK FOR DIVISION AND CLASS NUMBERS, ENTRY FEES, AND ENTRY CLOSING DATES TOTAL ENTRY FEES _____________________________ The undersign state herewith, that her/she is a recognized supervisor of the project of which the above entries are a part; that to his/her personal and actual knowledge the statements regarding the same are true; and he/she Amount Enclosed _____________________________ as read and has full understanding of the rules and regulations governing the Same and agrees to be governed by them. -

Regional Sr. High Hippology ID 2011

The following questions are multiple choice for all Sr. High Members. The possible answers are on each slide. You will have 20 seconds per slide this time through. We will also run through the slides a second time giving you an additional 10 seconds to make final answers. Get Ready here comes slide 1 Good Luck! 1 Identify this breed. A. Hackney C. Saddlebred B. Standardbred D. Arabian Using the Texas A&M Body Condition 2 Scoring system this horse would be a.. ? A. 3 C. 5 B. 7 D. 9 3 Identify this breed. A. Belgian C. Percheron B. Clydesdale D. Suffolk Punch 4 Identify this part. A. Croup C. Withers B. Poll D. Gaskin 5 Identify this color. A. Bay C. Black B. Chestnut D. Dun 6 Identify this breed. A. Lipizzan C. Andalusian B. Peruvian Paso D. Percheron Identify 7 the part labeled B. A. Cervix C. Uterus B. Vagina D. Oviduct Identify 8 this breeding practice. A. Live Cover C. Artificial Insemination B. Collecting D. Teasing Identify the 9 part of headstall A. Cheek Piece C. Latigo B. Browband D. Crown What vital 10 sign is being evaluated here. A. Capillary Refill C. Pulse B. Temperature D. Heart Rate 11 Identify this feed A. Corn C. Oats B. Barley D. Rye 12 Identify this part of the saddle. A. Panel C. Gullet B. Jockey D. Cantle 13 Identify these pieces of equip. A. Bell Boots C. Polo Wraps B. Splint Boots D. Skid Boots Identify the use of 14 this product. A. Vaccination C. Sedative B. -

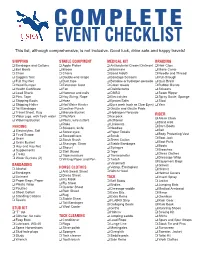

EVENT CHECKLIST This List, Although Comprehensive, Is Not Inclusive

COMPLETE EVENT CHECKLIST This list, although comprehensive, is not inclusive. Good luck, drive safe and happy travels! SHIPPING STABLE EQUIPMENT MEDICAL KIT BRAIDING ❑ Bandages and Cottons ❑ Apple Picker ❑ Antibacterial Cream/Ointment ❑ Hair Clips ❑ Bell Boots ❑ Broom ❑ Banamine ❑ Mane Comb ❑ Chain ❑ Chairs ❑ Band Aids® ❑ Needle and Thread ❑ Coggins Test ❑ Double-end snaps ❑ Bandage Scissors ❑ Pull-through ❑ Full Hay Net ❑ Duct tape ❑ Betadine or hydrogen peroxide ❑ Quic Braid ❑ Head Bumper ❑ Extension Cord ❑ Clean towels ❑ Rubber Bands ❑ Health Certificate ❑ Fan ❑ Disinfectants ❑ Scissors ❑ Lead Shank ❑ Hammer and nails ❑ DMSO ❑ Seam Ripper ❑ Pins, Tape ❑ Hay String, Rope ❑ Electrolytes ❑ Spray Bottle, Sponge ❑ Shipping Boots ❑ Hose ❑ Epsom Salts ❑ Stool ❑ Shipping Halter ❑ Hot Water Heater ❑ Eyes wash (such as Clear Eyes) ❑ Yarn ❑ Tail Bandages ❑ Leather Punch ❑ Gauze and Gauze Pads ❑ ❑ ❑ Travel Sheet, Rug Manure Bucket Hydrogen Peroxide RIDER ❑ Water jugs, with fresh water ❑ Pitchfork ❑ Ice pack ❑ Alarm Clock ❑ Watering Bucket ❑ Pliers, wire cutters ❑ Icthamol ❑ Band Aids ❑ Rake ❑ Liniments ❑ Barn Boots FEEDING ❑ Scissors, knife ❑ Needles ❑ ❑ Belt Electrolytes, Salt ❑ Screw eyes ❑ Paper Towels ❑ ❑ Body Protecting Vest Feed Scoop ❑ Screwdrivers ❑ Scrub ❑ ❑ Boot Jack Grain ❑ Scrub Brush ❑ Sheet Cotton ❑ ❑ Boot Pulls Grain Bucket ❑ Shavings, Straw ❑ Stable Bandages ❑ ❑ Boots Hay and Hay Net ❑ Shovel ❑ Syringes ❑ ❑ Breeches Supplements ❑ Stall Guard ❑ Tape ❑ ❑ Dress Clothes Treats ❑ Tape measure ❑ Thermometer ❑ ❑ Dressage Whip Water Buckets