IU History of Eclipses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hoosier Historical Hike

Welcome to the Hoosier Historical Hike. This hike was created by Scouts from the Wapahani District and the Hoosier Trails Council. This experience is a great way to learn about the history of Bloomington, Indiana. You will enjoy a three-phase hike that totals 5.5 miles in some of the most beautiful parts of the state. You can complete these hikes all at once or in different segments. The segments will include the downtown Bloomington area, Rose Hill Cemetery, and the Indiana University Campus. You will find 43 stops along these scenic routes. Please use the attached coordinates to find all the great locations and just for fun, we have added some great questions that you can research along the way! Keep in mind: One person should in charge of the documents and writing down the answers from the other members of the group. You will need the following for this hike: • Comfortable hiking foot ware • Appropriate seasonal clothing • A first aid kit • A copy of these documents • A pad of paper • Two pens or pencils • A cell phone that has a compass and a coordination app. • A trash bag • Water Bottle It is recommended that you wear you Scout Uniform or Class B’s. Remember, you are Scouts and during this hike you are representing the Scouting movement. You will be walking through neighborhoods so please respect private property. Do not liter and if you see liter please place it in your trash bag and properly dispose it. Remember leave no trace, take only photographs and memories. During this pandemic some of the buildings will be closed. -

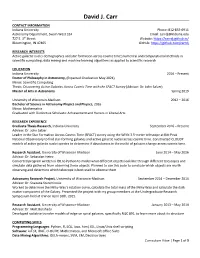

David J. Carr

David J. Carr CONTACT INFORMATION Indiana University Phone: 812-855-6911 Astronomy Department, Swain West 324 Email: [email protected] 727 E. 3rd Street Website: https://carrdj.github.io/ Bloomington, IN 47405 GitHub: https://github.com/carrdj RESEARCH INTERESTS Active galactic nuclei demographics and star formation across cosmic time; numerical and computational methods in scientific computing; data mining and machine learning algorithms as applied to scientific research EDUCATION Indiana University 2016 – Present Doctor of Philosophy in Astronomy, (Expected Graduation May 2021) Minor: Scientific Computing Thesis: Discovering Active Galaxies Across Cosmic Time with the SFACT Survey (Advisor: Dr. John Salzer) Master of Arts in Astronomy Spring 2019 University of Wisconsin-Madison 2012 – 2016 Bachelor of Science in Astronomy-Physics and Physics, 2016 Minor: Mathematics Graduated with Distinctive Scholastic Achievement and Honors in Liberal Arts RESEARCH EXPERIENCE Graduate Thesis Research, Indiana University September 2016 – Present Advisor: Dr. John Salzer Leader in the Star Formation Across Cosmic Time (SFACT) survey using the WIYN 3.5-meter telescope at Kitt Peak National Observatory to find star-forming galaxies and active galactic nuclei across cosmic time. Constructed CLOUDY models of active galactic nuclei spectra to determine if abundances in the nuclei of galaxies change across cosmic time. Research Assistant, University of Wisconsin-Madison June 2014 – May 2016 Advisor: Dr. Sebastian Heinz Converted program written in IDL to Python to model what different objects look like through different telescopes and simulate data gathered from observing these objects. Planned to use this code to conclude which objects are worth observing and determine which telescope is best used to observe them. -

The Kirkwood Society

The Kirkwood Society A Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Astronomy Department at Indiana University Editor: Kent Honeycutt Composition: Christina Lirot Summer 2001 This has been another busy and productive year for the department. Our undergraduate major program remains strong, with nine graduating in May. The WIYN Observatory remains our primary instrument for graduate research and continues to provide world-class performance for image quality and multiple -object spectroscopy. Research activities have taken our students and faculty to Venezuela, Italy, Germany, and Japan, as well as other global locations this past year. These travels, along with current graduate students from Greece, Venezuela, and China, remind us daily of how astronomy has become a truly international enterprise. Be sure to visit our newly revised Web site at www.astro.indiana.edu to learn about these and other programs of the department. Kirkwood Observatory: The renovation of the telescope itself is being done by the Renovation of the Kirkwood Observatory has finally begun! Astronomy Department. The telescope is now nearly Work on the building and dome, performed by a professional completely disassembled for repair and refurbishment. With historical renovation contractor, will retain the 1900-1950 new paint, clean optics, and polished brass, we think the look and feel. The functions of the telescope and telescope will look very similar to when it received the observatory will be preserved insofar as Wednesday Public majority of its use this past century. The Kirkwood 12-inch Night and use of the telescope for viewing the moon and telescope was used extensively in our Observational planets by students in our descriptive astronomy classes. -

Indiana University

TABLE OF CONTENTS 2005-06WRESTLING INTRODUCTION SEASON IN REVIEW Quick Facts and Media Information . .3 Season in Review . .46 Schedule and University Gym Information . .4 Match-by-Match . .48 Roster and Pronunciation Guide . .5 Big Ten & NCAA Championships . .51 Wrestling Preview . .6 Season Honors & Statistics . .52 Rules of Wrestling . .8 Big Ten Conference . .9 HISTORY AND RECORDS Photo Roster . .10 All-Americans . .54 NCAA Champions & All-Americans . .59 MEET THE WRESTLERS Big Ten Championships . .60 Brandon Becker . .12 Academic Honors . .61 Max Dean . .13 Season & Career Records . .62 Joe Dubuque . .14 Coaching History . .63 Isaac Knable . .15 Year-by-Year . .65 Brady Richardson . .16 All-Time Results . .67 Returning Letterwinners/Redshirts . .17 Letterwinners . .75 Newcomers . .22 Hometowns . .78 2005-06 Team . .25 IU Wrestling Tradition . .26 THIS IS INDIANA Indiana University . .88 STAFF Academic Recognition . .91 Head Coach Duane Goldman . .28 Academic Choices . .92 Assistant Coach Mike Mena . .30 Athletic Academic Services . .94 Assistant Coach Reggie Wright . .31 Student Life . .96 Volunteer Coach Coyte Cooper . .31 Student Development & Diversity . .97 Strength and Conditioning Coach Josh Eidson . .32 Campus Map . .98 Trainer Kip Smith . .32 Alumni . .99 Bloomington . .100 OPPONENTS Indianapolis . .101 Opponents . .34 Winning Tradition . .102 Series Results . .36 Wrestling Facilities . .104 IU Wrestling Tradition . .105 Athletic Facilities . .106 G Stronger & Faster . .108 N I 2005-06 INDIANA WRESTLING MEDIA GUIDE L T The 2004-05 Indiana Wrestling Media Guide is a Cover Design Beth Feickert Photography Paul Riley S production of the Indiana Media Relations Writing Kevin Martinez Presswork Metropolitan Printing, Editing IU Media Relations Staff Bloomington, Ind. E Office. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

Daniel Kirkwood Frank K. Edmondson Department of Astronomy, Indiana University Bloomington, Indiana 47405 Kirkwood Avenue, Kirkwood Hall and Kirkwood Observatory are visible memorials to Daniel Kirkwood. He must have been an important person to merit such recogni- tion, but very few people today know why he was important. This symposium gives me an opportunity to do something to revive public appreciation for this man. This talk will have four major parts: 1) Indiana University prior to Kirk wood's arrival, 2) Chronology of Kirkwood's life, 3) Daniel Kirkwood at Indiana University and his work as a scientist, and 4) Daniel Kirkwood and the Indiana Academy of Science. I.U. had three faculty members after Andrew Wylie became President in 1829, and one of them offered instruction in Astronomy. Daniel Kirkwood was 15 years old at this time. The faculty had grown to about half a dozen by the time Kirkwood arrived and numbered about a dozen when he retired. Astronomy was listed in the course of instruction as a Senior Year Course in both the Regular and Scientific Courses in 1856. In 1880 it was listed in all three curricula: Ancient Classics, Modern Classics, and Science. Daniel Kirkwood was six years old when the Indiana State Seminary was found- ed in 1820. He was 42 years old when he joined the I.U. faculty in 1856. Table I gives selected dates and events in his life. His first U.S. demonstration of the Foucault Pendulum in 1851 only a few months after it was demonstrated in Paris is an example of his pioneering spirit, inquiring mind, and knowledge of contemporary science in Europe. -

The Kirkwood Society a Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Astronomy Department at Indiana University Summer/Fall 2003

The Kirkwood Society A Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Astronomy Department at Indiana University Summer/Fall 2003 Greetings from the Chairman! Special thanks, as always, to all the friends and alumni of the It is hard to believe another year has gone by, and it has Department who have supported us generously over the last been a full one. The Department is more vigorous than year. Much of what we do depends on you. Please visit the ever. All faculty members have grants for teaching and/or Department’s web page (see p. 8) for more information about research projects and are actively pursuing investigations our activities and please feel free to contact me by email at on everything from neutrino oscillations and planet [email protected]. formation, on the smaller scales, to surveys of dwarf galaxies and the nature of dark energy on the larger Discovery in the Classroom scales. Of course, if you know this Department, and you presumably do if you receive this Newsletter, you know Research Experience for Introductory that we also do lots and lots of research on the stellar and Astronomy Students galactic scales in between. At the same time, many faculty and graduate students are involved in a wide range of innovative teaching and outreach initiatives, which include development of sixth grade units on the origins of planetary systems and incorporation of real hands-on research experiences into our courses for both majors and nonmajors. Due to our recent increase in faculty size, we are now able to provide more varied undergraduate offerings, including some courses with smaller class sizes on a range of special topics, like astrobiology and cosmology. -

Alumni • Magazine ~~~~~~~~~

THE • MARCH • 1940 ALUMNI • MAGAZINE ~~~~~~~~~ ~ " ~" - ~~':sier ~l~~~:e ~ > . PI ! I ~ March By William C. FitzGibbon, '40 31 Day. i ~ ~ ~.' : 8 Ed Kemp and his fa III 0 u::; 1940 March 1940 who was forced to cancel his ; .~~r!~~<1 band return to the campus to pay1 engagement. ~ ', ~b for all Gther Junior Prom . .. S M T W T F S 'Jp ~j Kemp's Inusicians made a last· '" '" * * * 1 2 19 Campus beauties will be the ~ Ing impression hack in '3·1. Rt the 3 4 5 6 7 center of interest today as The ~ top social event on the campus. 8 9 ArbUlllS, University yearbook, se ~ 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 lects its beauties to be featured ~~~., j,.~ 9 Today the Big Ten champion- 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 in the 1940 issue of the book ~~ ships HI track, wrestling and 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 ... This year the contest will b~ sWlInlllmg "ill be deci ded III 31 ~: ::: '" * * * held in Alull1ni Hall instead of "~ ~ tourneys at Chicago, P urdue and in a downtown theatre. ~! Michigan, rcspeclively. The pre ~ liminary trials we re held yesterday. 21 One year ago 31 members of the Men's Glee Club started out on a tOllr of ten Indiana cities. ~.,~· 10 Today and every Sunday morning the Uni versity has two regular radio programs: "Editorial 22 Today, Good Friday, the Uni versity Sym i~ of the Air," over WIRE of Indianapolis, 9:00-9:30, phony, under the direction of Dean Robert Sanders , and "Everyman's Campus of the Air," over WHAS of the School of Music, will present all Easter pro I of Louisville, 11 :30-12 :00. -

Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science

NECROLOGY Will E. Edington, DePauw University Wilbur Adelman Cogshall Mendon, Michigan Rockford, Illinois February 8, 1874 October 5, 1951 The real history of astronomy in the United States goes back only a little over a century to the founding of the Yale Observatory in 1830. This was followed by the founding of the Harvard Observa- tory in 1839, the U. S. Naval Observatory in 1840, and the University of Cincinnati Observatory in 1843. During the first half of the last century astronomy was taught in many colleges and universities as a part of a junior or senior course in navigation or natural philosophy. The nineteenth century produced not over a dozen Americans who, during that century, made significant contributions to astronomical knowledge, and one of these was Daniel Kirkwood, (1814-1894), who came to Indiana University in 1856 and remained there thirty years. He was sometimes referred to as "The Kepler of America." Kirkwood Observatory at Indiana University was named in his honor. The first Director of Kirkwood Observatory was John A. Miller, (1859- 1946), an Indiana University alumnus, who was Professor of Mathe- matics and Astronomy at Indiana University from 1894 to 1906. During Dr. Miller's directorship graduate study in astronomy was developed and the first A.M. degree in astronomy granted in 1899. It was three years later before the next two advanced degrees were granted and the recipient of one of these was Wilbur Adelman Cogshall, who had come to Indiana University in 1900 as an instructor in mechanics and astronomy. Wilbur Adelman Cogshall was born in Mendon, Michigan, on February 8, 1874. -

2005-06 Women's Golf

INDIANA HAS ITS SIGHTS SET ON QUALIFYING FOR ITS FIRST NCAA TOURNAMENT APPEARANCE SINCE 1998. 2005-06 WOMEN’S GOLF TABLE OF CONTENTS/ROSTER 2005-06WOMEN’S GOLF IU WOMEN’S GOLF 2004-05 IN REVIEW Media Information . .3 2004-05 Season in Review . .28 Quick Facts and Schedule . .4 2004-05 Team Results . .31 2003-04 Individual Results . .32 2005-06 PREVIEW 2005-06 Season Preview . .6 THIS IS INDIANA GOLF 2005-06 Tournaments . .8 Tradition . .34 Big Ten Championship Preview . .10 IU Golf Course . .36 IU Practice Facility . .39 COACHING STAFF Head Coach Clint Wallman . .12 HISTORY & RECORDS Assistant Coach Jeana Finlinson . .13 Hoosiers on the LPGA Tour . .42 Support Staff . .14 All-Americans . .45 All-Time Results . .47 MEET THE HOOSIERS Former Coaches . .52 Katie Carlson . .16 Individual Records . .53 Kendal Hake . .17 Team Records . .54 Elaine Harris . .18 Records & Honors . .55 Shannon Johnson . .19 Postseason Honors . .58 Gennifer Marrs . .20 Letterwinners . .59 Molly Redfearn . .21 Roster By Hometown . .64 Tara Boone/Tiffany Hockensmih . .22 Jenny Kim/Amber Lindgren . .23 IU EXPERIENCE Career Meet-By-Meet . .24 Indiana University . .66 Spotting Chart . .25 Big Ten Conference . .26 2005-06 INDIANA WOMEN’S GOLF ROSTER NAME YR./ELG. HT. HOMETOWN HIGH SCHOOL Tara Boone Fr./HS 5-3 Huntington, Ind. Huntington Katie Carlson Sr./3L 5-7 Livonia, Mich. Stevenson Kendal Hake So./1L 5-7 Palatine, Ill. William Fremd Elaine Harris So./1L 5-8 San Francisco, Calif. St. Ignatius Tiffany Hockensmith Fr./HS 5-5 Bloomington, Ind. South Shannon Johnson Sr./3L 5-8 Sioux Falls, S.D. -

Campus Walking Tour

Indiana University iub.edu Bloomington Campus tours “The campus should be a place of beauty that students can walk around and think grand thoughts.” —Herman B Wells Indiana University President 1938–1962 Campus Tours Old Crescent Tour The Indiana University Bloomington main campus is surprisingly compact, but there is 1 even more to see outside our gates. A walking tour is usually the best way to appreciate the natural beauty and architectural details that make this campus so remarkable; there is a driving tour available for our most distant attractions. Choose from excursions that enlighten you on the early history of the campus or that introduce you to our latest athletic additions. From a serene stroll to a hearty hike, there is something for everyone’s taste. Map Key Take one or more self-guided tours depending on your 2 Discovery Tour schedule and interests. 1 Old Crescent Tour (22-minute walk) Architecture abounds on this tour of the oldest buildings on campus. 2 Discovery Tour (30-minute walk) If the sciences are your area of interest, this tour is for you. 3 Big Union Tour (32-minute walk) The hub for students on campus is the center of this tour. 4 Tenth Street Tour (12-minute walk) Big Union Tour 23 A sampling of schools from business to psychology. 5 Fine Arts Tour (34-minute walk) 3 All the world’s a stage and you, a visitor upon it. 6 Cream and Crimson Tour (58-minute walk) Experience the athletics complex up close and personal. 7 Off the Beaten Path Tour (56-minute walk) From the esoteric to the gastronomic, see the landmarks outside our gates. -

The Kirkwood Society a Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Astronomy Department at Indiana University Editor: Richard H

The Kirkwood Society A Newsletter for Alumni and Friends of the Astronomy Department at Indiana University Editor: Richard H. Durisen Compositor: Christina Lirot Summer/Fall 2002 Greetings from the Chairman! October Astrofest Astronomy has a long and splendid tradition at Indiana Due to the confluence of two very special occasions (see p. University going back to Prof. Daniel Kirkwood's 2), the rededication of a renovated Kirkwood Observatory distinguished research on asteroids, comets, and meteors and the 90th Birthday of Professor Emeritus Frank K. in the mid -Nineteenth Century. In light of this, it is with Edmondson, the Department of Astronomy will be hosting a more that a little trepidation that I have begun a three-year weekend of activities called Astrofest for our friends, alumni, term as Department Chairman this July. The previous and community. We have a lot to celebrate at the beginning Chairman, R. Kent Honeycutt, has certainly left me with a of the new Millennium -- a long, rich history, a renewed and rather large swivel chair to fill. Kent's achievements vigorous present, and the promise of an exciting future. We during five years as Chair have been huge, including the hope you will be able to join us for some or all of these renovation and creation of valuable local facilities, festivities. The following schedule of events is in summary enhancement of our financial commitment to participation form. We will be sending more detailed information soon in the WIYN Consortium, recruitment and nurture of after this Newsletter, including a reservation form for the excellent young faculty members, and the addition to our Edmondson dinner. -

Stylebook Addendum for Spring 2019

INDIANA DAILY STUDENT Stylebook addendum for spring 2019 Indiana Daily Student | idsnews.com | Monday, Oct. 29, 2018 7 Bob Knight never Bobby unless in a For those with a location name in direct quote their proper titles, use it: University of NEWS California at Los Angeles, University ANALYSIS capitalization UNIVERSITY: Lowercase of Texas at Arlington. Usually there’s IU employees gave over university as a reference to IU. See also no need for this when referring to $175,000 to political campaigns plurals. a university’s main campus, unless A look into political contributions by IU employees indicates that faculty and staff in the more than one is mentioned or the College of Arts and Sciences gave the most, followed by the Maurer School of Law. CRABB Band Part of the IU Marching By Jesse Naranjo and Matt Rasnic college system has more than one main [email protected] | [email protected] Hundred that plays at soccer games. campus. Well-known abbreviations, Government OfficialsReverted back to $20,328 including UCLA, UNLV, USC, UTEP previous IDS style. Maurer School of Law and LSU, are acceptable on second See government officials. and subsequent references. Never use abbreviations that readers would not $76,595 IU Foundation on first reference. The $19,822 easily recognize. College of Arts and Sciences foundation on second reference. Misc. staff Spell out State as part of a proper name, such as Michigan State. LGBTQ Use LGBTQ as per AP style. $12,042 For sports, all schools outside Use neither form as a noun. Jacobs School the BIG Ten conference need to be of Music LGBTQ also includes queer $10,036 identified by their full name on first $9,560 and/or questioning.