3.2 the Momentum Principles

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary Physics (I-Introduction)

1 Glossary Physics (I-introduction) - Efficiency: The percent of the work put into a machine that is converted into useful work output; = work done / energy used [-]. = eta In machines: The work output of any machine cannot exceed the work input (<=100%); in an ideal machine, where no energy is transformed into heat: work(input) = work(output), =100%. Energy: The property of a system that enables it to do work. Conservation o. E.: Energy cannot be created or destroyed; it may be transformed from one form into another, but the total amount of energy never changes. Equilibrium: The state of an object when not acted upon by a net force or net torque; an object in equilibrium may be at rest or moving at uniform velocity - not accelerating. Mechanical E.: The state of an object or system of objects for which any impressed forces cancels to zero and no acceleration occurs. Dynamic E.: Object is moving without experiencing acceleration. Static E.: Object is at rest.F Force: The influence that can cause an object to be accelerated or retarded; is always in the direction of the net force, hence a vector quantity; the four elementary forces are: Electromagnetic F.: Is an attraction or repulsion G, gravit. const.6.672E-11[Nm2/kg2] between electric charges: d, distance [m] 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (q1q2/d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] m,M, mass [kg] Gravitational F.: Is a mutual attraction between all masses: q, charge [As] [C] 2 2 2 2 F = GmM/d [Nm /kg kg 1/m ] = [N] 0, dielectric constant Strong F.: (nuclear force) Acts within the nuclei of atoms: 8.854E-12 [C2/Nm2] [F/m] 2 2 2 2 2 F = 1/(40) (e /d ) [(CC/m )(Nm /C )] = [N] , 3.14 [-] Weak F.: Manifests itself in special reactions among elementary e, 1.60210 E-19 [As] [C] particles, such as the reaction that occur in radioactive decay. -

Key Concepts for Future QIS Learners Workshop Output Published Online May 13, 2020

Key Concepts for Future QIS Learners Workshop output published online May 13, 2020 Background and Overview On behalf of the Interagency Working Group on Workforce, Industry and Infrastructure, under the NSTC Subcommittee on Quantum Information Science (QIS), the National Science Foundation invited 25 researchers and educators to come together to deliberate on defining a core set of key concepts for future QIS learners that could provide a starting point for further curricular and educator development activities. The deliberative group included university and industry researchers, secondary school and college educators, and representatives from educational and professional organizations. The workshop participants focused on identifying concepts that could, with additional supporting resources, help prepare secondary school students to engage with QIS and provide possible pathways for broader public engagement. This workshop report identifies a set of nine Key Concepts. Each Concept is introduced with a concise overall statement, followed by a few important fundamentals. Connections to current and future technologies are included, providing relevance and context. The first Key Concept defines the field as a whole. Concepts 2-6 introduce ideas that are necessary for building an understanding of quantum information science and its applications. Concepts 7-9 provide short explanations of critical areas of study within QIS: quantum computing, quantum communication and quantum sensing. The Key Concepts are not intended to be an introductory guide to quantum information science, but rather provide a framework for future expansion and adaptation for students at different levels in computer science, mathematics, physics, and chemistry courses. As such, it is expected that educators and other community stakeholders may not yet have a working knowledge of content covered in the Key Concepts. -

Non-Local Momentum Transport Parameterizations

Non-local Momentum Transport Parameterizations Joe Tribbia NCAR.ESSL.CGD.AMP Outline • Historical view: gravity wave drag (GWD) and convective momentum transport (CMT) • GWD development -semi-linear theory -impact • CMT development -theory -impact Both parameterizations of recent vintage compared to radiation or PBL GWD CMT • 1960’s discussion by Philips, • 1972 cumulus vorticity Blumen and Bretherton damping ‘observed’ Holton • 1970’s quantification Lilly • 1976 Schneider and and momentum budget by Lindzen -Cumulus Friction Swinbank • 1980’s NASA GLAS model- • 1980’s incorporation into Helfand NWP and climate models- • 1990’s pressure term- Miller and Palmer and Gregory McFarlane Atmospheric Gravity Waves Simple gravity wave model Topographic Gravity Waves and Drag • Flow over topography generates gravity (i.e. buoyancy) waves • <u’w’> is positive in example • Power spectrum of Earth’s topography α k-2 so there is a lot of subgrid orography • Subgrid orography generating unresolved gravity waves can transport momentum vertically • Let’s parameterize this mechanism! Begin with linear wave theory Simplest model for gravity waves: with Assume w’ α ei(kx+mz-σt) gives the dispersion relation or Linear theory (cont.) Sinusoidal topography ; set σ=0. Gives linear lower BC Small scale waves k>N/U0 decay Larger scale waves k<N/U0 propagate Semi-linear Parameterization Propagating solution with upward group velocity In the hydrostatic limit The surface drag can be related to the momentum transport δh=isentropic Momentum transport invariant by displacement Eliassen-Palm. Deposited when η=U linear theory is invalid (CL, breaking) z φ=phase Gravity Wave Drag Parameterization Convective or shear instabilty begins to dissipate wave- momentum flux no longer constant Waves propagate vertically, amplitude grows as r-1/2 (energy force cons.). -

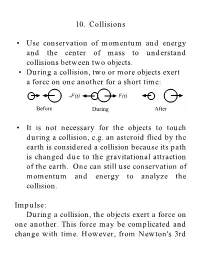

10. Collisions • Use Conservation of Momentum and Energy and The

10. Collisions • Use conservation of momentum and energy and the center of mass to understand collisions between two objects. • During a collision, two or more objects exert a force on one another for a short time: -F(t) F(t) Before During After • It is not necessary for the objects to touch during a collision, e.g. an asteroid flied by the earth is considered a collision because its path is changed due to the gravitational attraction of the earth. One can still use conservation of momentum and energy to analyze the collision. Impulse: During a collision, the objects exert a force on one another. This force may be complicated and change with time. However, from Newton's 3rd Law, the two objects must exert an equal and opposite force on one another. F(t) t ti tf Dt From Newton'sr 2nd Law: dp r = F (t) dt r r dp = F (t)dt r r r r tf p f - pi = Dp = ò F (t)dt ti The change in the momentum is defined as the impulse of the collision. • Impulse is a vector quantity. Impulse-Linear Momentum Theorem: In a collision, the impulse on an object is equal to the change in momentum: r r J = Dp Conservation of Linear Momentum: In a system of two or more particles that are colliding, the forces that these objects exert on one another are internal forces. These internal forces cannot change the momentum of the system. Only an external force can change the momentum. The linear momentum of a closed isolated system is conserved during a collision of objects within the system. -

Lecture 10: Impulse and Momentum

ME 230 Kinematics and Dynamics Wei-Chih Wang Department of Mechanical Engineering University of Washington Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum Chapter 15 Chapter objectives • Develop the principle of linear impulse and momentum for a particle • Study the conservation of linear momentum for particles • Analyze the mechanics of impact • Introduce the concept of angular impulse and momentum • Solve problems involving steady fluid streams and propulsion with variable mass W. Wang Lecture 10 • Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum (Chapter 15) - 15.1-15.3 W. Wang Material covered • Kinetics of a particle: Impulse and Momentum - Principle of linear impulse and momentum - Principle of linear impulse and momentum for a system of particles - Conservation of linear momentum for a system of particles …Next lecture…Impact W. Wang Today’s Objectives Students should be able to: • Calculate the linear momentum of a particle and linear impulse of a force • Apply the principle of linear impulse and momentum • Apply the principle of linear impulse and momentum to a system of particles • Understand the conditions for conservation of momentum W. Wang Applications 1 A dent in an automotive fender can be removed using an impulse tool, which delivers a force over a very short time interval. How can we determine the magnitude of the linear impulse applied to the fender? Could you analyze a carpenter’s hammer striking a nail in the same fashion? W. Wang Applications 2 Sure! When a stake is struck by a sledgehammer, a large impulsive force is delivered to the stake and drives it into the ground. -

Exercises in Classical Mechanics 1 Moments of Inertia 2 Half-Cylinder

Exercises in Classical Mechanics CUNY GC, Prof. D. Garanin No.1 Solution ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||| 1 Moments of inertia (5 points) Calculate tensors of inertia with respect to the principal axes of the following bodies: a) Hollow sphere of mass M and radius R: b) Cone of the height h and radius of the base R; both with respect to the apex and to the center of mass. c) Body of a box shape with sides a; b; and c: Solution: a) By symmetry for the sphere I®¯ = I±®¯: (1) One can ¯nd I easily noticing that for the hollow sphere is 1 1 X ³ ´ I = (I + I + I ) = m y2 + z2 + z2 + x2 + x2 + y2 3 xx yy zz 3 i i i i i i i i 2 X 2 X 2 = m r2 = R2 m = MR2: (2) 3 i i 3 i 3 i i b) and c): Standard solutions 2 Half-cylinder ϕ (10 points) Consider a half-cylinder of mass M and radius R on a horizontal plane. a) Find the position of its center of mass (CM) and the moment of inertia with respect to CM. b) Write down the Lagrange function in terms of the angle ' (see Fig.) c) Find the frequency of cylinder's oscillations in the linear regime, ' ¿ 1. Solution: (a) First we ¯nd the distance a between the CM and the geometrical center of the cylinder. With σ being the density for the cross-sectional surface, so that ¼R2 M = σ ; (3) 2 1 one obtains Z Z 2 2σ R p σ R q a = dx x R2 ¡ x2 = dy R2 ¡ y M 0 M 0 ¯ 2 ³ ´3=2¯R σ 2 2 ¯ σ 2 3 4 = ¡ R ¡ y ¯ = R = R: (4) M 3 0 M 3 3¼ The moment of inertia of the half-cylinder with respect to the geometrical center is the same as that of the cylinder, 1 I0 = MR2: (5) 2 The moment of inertia with respect to the CM I can be found from the relation I0 = I + Ma2 (6) that yields " µ ¶ # " # 1 4 2 1 32 I = I0 ¡ Ma2 = MR2 ¡ = MR2 1 ¡ ' 0:3199MR2: (7) 2 3¼ 2 (3¼)2 (b) The Lagrange function L is given by L('; '_ ) = T ('; '_ ) ¡ U('): (8) The potential energy U of the half-cylinder is due to the elevation of its CM resulting from the deviation of ' from zero. -

Impact Dynamics of Newtonian and Non-Newtonian Fluid Droplets on Super Hydrophobic Substrate

IMPACT DYNAMICS OF NEWTONIAN AND NON-NEWTONIAN FLUID DROPLETS ON SUPER HYDROPHOBIC SUBSTRATE A Thesis Presented By Yingjie Li to The Department of Mechanical and Industrial Engineering in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in the field of Mechanical Engineering Northeastern University Boston, Massachusetts December 2016 Copyright (©) 2016 by Yingjie Li All rights reserved. Reproduction in whole or in part in any form requires the prior written permission of Yingjie Li or designated representatives. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I hereby would like to appreciate my advisors Professors Kai-tak Wan and Mohammad E. Taslim for their support, guidance and encouragement throughout the process of the research. In addition, I want to thank Mr. Xiao Huang for his generous help and continued advices for my thesis and experiments. Thanks also go to Mr. Scott Julien and Mr, Kaizhen Zhang for their invaluable discussions and suggestions for this work. Last but not least, I want to thank my parents for supporting my life from China. Without their love, I am not able to complete my thesis. TABLE OF CONTENTS DROPLETS OF NEWTONIAN AND NON-NEWTONIAN FLUIDS IMPACTING SUPER HYDROPHBIC SURFACE .......................................................................... i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................... iii 1. INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................. 9 1.1 Motivation ........................................................................................................ -

Post-Newtonian Approximation

Post-Newtonian gravity and gravitational-wave astronomy Polarization waveforms in the SSB reference frame Relativistic binary systems Effective one-body formalism Post-Newtonian Approximation Piotr Jaranowski Faculty of Physcis, University of Bia lystok,Poland 01.07.2013 P. Jaranowski School of Gravitational Waves, 01{05.07.2013, Warsaw Post-Newtonian gravity and gravitational-wave astronomy Polarization waveforms in the SSB reference frame Relativistic binary systems Effective one-body formalism 1 Post-Newtonian gravity and gravitational-wave astronomy 2 Polarization waveforms in the SSB reference frame 3 Relativistic binary systems Leading-order waveforms (Newtonian binary dynamics) Leading-order waveforms without radiation-reaction effects Leading-order waveforms with radiation-reaction effects Post-Newtonian corrections Post-Newtonian spin-dependent effects 4 Effective one-body formalism EOB-improved 3PN-accurate Hamiltonian Usage of Pad´eapproximants EOB flexibility parameters P. Jaranowski School of Gravitational Waves, 01{05.07.2013, Warsaw Post-Newtonian gravity and gravitational-wave astronomy Polarization waveforms in the SSB reference frame Relativistic binary systems Effective one-body formalism 1 Post-Newtonian gravity and gravitational-wave astronomy 2 Polarization waveforms in the SSB reference frame 3 Relativistic binary systems Leading-order waveforms (Newtonian binary dynamics) Leading-order waveforms without radiation-reaction effects Leading-order waveforms with radiation-reaction effects Post-Newtonian corrections Post-Newtonian spin-dependent effects 4 Effective one-body formalism EOB-improved 3PN-accurate Hamiltonian Usage of Pad´eapproximants EOB flexibility parameters P. Jaranowski School of Gravitational Waves, 01{05.07.2013, Warsaw Relativistic binary systems exist in nature, they comprise compact objects: neutron stars or black holes. These systems emit gravitational waves, which experimenters try to detect within the LIGO/VIRGO/GEO600 projects. -

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1

Fluids – Lecture 7 Notes 1. Momentum Flow 2. Momentum Conservation Reading: Anderson 2.5 Momentum Flow Before we can apply the principle of momentum conservation to a fixed permeable control volume, we must first examine the effect of flow through its surface. When material flows through the surface, it carries not only mass, but momentum as well. The momentum flow can be described as −→ −→ momentum flow = (mass flow) × (momentum /mass) where the mass flow was defined earlier, and the momentum/mass is simply the velocity vector V~ . Therefore −→ momentum flow =m ˙ V~ = ρ V~ ·nˆ A V~ = ρVnA V~ where Vn = V~ ·nˆ as before. Note that while mass flow is a scalar, the momentum flow is a vector, and points in the same direction as V~ . The momentum flux vector is defined simply as the momentum flow per area. −→ momentum flux = ρVn V~ V n^ . mV . A m ρ Momentum Conservation Newton’s second law states that during a short time interval dt, the impulse of a force F~ applied to some affected mass, will produce a momentum change dP~a in that affected mass. When applied to a fixed control volume, this principle becomes F dP~ a = F~ (1) dt V . dP~ ˙ ˙ P(t) P + P~ − P~ = F~ (2) . out dt out in Pin 1 In the second equation (2), P~ is defined as the instantaneous momentum inside the control volume. P~ (t) ≡ ρ V~ dV ZZZ ˙ The P~ out is added because mass leaving the control volume carries away momentum provided ˙ by F~ , which P~ alone doesn’t account for. -

Foundations of Continuum Mechanics

Foundations of Continuum Mechanics • Concerned with material bodies (solids and fluids) which can change shape when loaded, and view is taken that bodies are continuous bodies. • Commonly known that matter is made up of discrete particles, and only known continuum is empty space. • Experience has shown that descriptions based on continuum modeling is useful, provided only that variation of field quantities on the scale of deformation mechanism is small in some sense. Goal of continuum mechanics is to solve BVP. The main steps are 1. Mathematical preliminaries (Tensor theory) 2. Kinematics 3. Balance laws and field equations 4. Constitutive laws (models) Mathematical structure adopted to ensure that results are coordinate invariant and observer invariant and are consistent with material symmetries. Vector and Tensor Theory Most tensors of interest in continuum mechanics are one of the following type: 1. Symmetric – have 3 real eigenvalues and orthogonal eigenvectors (eg. Stress) 2. Skew-Symmetric – is like a vector, has an associated axial vector (eg. Spin) 3. Orthogonal – describes a transformation of basis (eg. Rotation matrix) → 3 3 3 u = ∑uiei = uiei T = ∑∑Tijei ⊗ e j = Tijei ⊗ e j i=1 ~ ij==1 1 When the basis ei is changed, the components of tensors and vectors transform in a specific way. Certain quantities remain invariant – eg. trace, determinant. Gradient of an nth order tensor is a tensor of order n+1 and divergence of an nth order tensor is a tensor of order n-1. ∂ui ∂ui ∂Tij ∇ ⋅u = ∇ ⊗ u = ei ⊗ e j ∇ ⋅ T = e j ∂xi ∂x j ∂xi Integral (divergence) Theorems: T ∫∫RR∇ ⋅u dv = ∂ u⋅n da ∫∫RR∇ ⊗ u dv = ∂ u ⊗ n da ∫∫RR∇ ⋅ T dv = ∂ T n da Kinematics The tensor that plays the most important role in kinematics is the Deformation Gradient x(X) = X + u(X) F = ∇X ⊗ x(X) = I + ∇X ⊗ u(X) F can be used to determine 1. -

Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Operated by Battelie for the U.S

PNNL-11668 UC-2030 Pacific Northwest National Laboratory Operated by Battelie for the U.S. Department of Energy Seismic Event-Induced Waste Response and Gas Mobilization Predictions for Typical Hanf ord Waste Tank Configurations H. C. Reid J. E. Deibler 0C1 1 0 W97 OSTI September 1997 •-a Prepared for the US. Department of Energy under Contract DE-AC06-76RLO1830 1» DISCLAIMER This report was prepared as an account of work sponsored by an agency of the United States Government, Neither the United States Government nor any agency thereof, nor Battelle Memorial Institute, nor any of their employees, makes any warranty, express or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of any information, apparatus, product, or process disclosed, or represents that its use would not infringe privately owned rights. Reference herein to any specific commercial product, process, or service by trade name, trademark, manufacturer, or otherwise does not necessarily constitute or imply its endorsement, recommendation, or favoring by the United States Government or any agency thereof, or Battelle Memorial Institute. The views and opinions of authors expressed herein do not necessarily state or reflect those of the United States Government or any agency thereof. PACIFIC NORTHWEST NATIONAL LABORATORY operated by BATTELLE for the UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF ENERGY under Contract DE-AC06-76RLO 1830 Printed in the United States of America Available to DOE and DOE contractors from the Office of Scientific and Technical Information, P.O. Box 62, Oak Ridge, TN 37831; prices available from (615) 576-8401, Available to the public from the National Technical Information Service, U.S. -

Apollonian Circle Packings: Dynamics and Number Theory

APOLLONIAN CIRCLE PACKINGS: DYNAMICS AND NUMBER THEORY HEE OH Abstract. We give an overview of various counting problems for Apol- lonian circle packings, which turn out to be related to problems in dy- namics and number theory for thin groups. This survey article is an expanded version of my lecture notes prepared for the 13th Takagi lec- tures given at RIMS, Kyoto in the fall of 2013. Contents 1. Counting problems for Apollonian circle packings 1 2. Hidden symmetries and Orbital counting problem 7 3. Counting, Mixing, and the Bowen-Margulis-Sullivan measure 9 4. Integral Apollonian circle packings 15 5. Expanders and Sieve 19 References 25 1. Counting problems for Apollonian circle packings An Apollonian circle packing is one of the most of beautiful circle packings whose construction can be described in a very simple manner based on an old theorem of Apollonius of Perga: Theorem 1.1 (Apollonius of Perga, 262-190 BC). Given 3 mutually tangent circles in the plane, there exist exactly two circles tangent to all three. Figure 1. Pictorial proof of the Apollonius theorem 1 2 HEE OH Figure 2. Possible configurations of four mutually tangent circles Proof. We give a modern proof, using the linear fractional transformations ^ of PSL2(C) on the extended complex plane C = C [ f1g, known as M¨obius transformations: a b az + b (z) = ; c d cz + d where a; b; c; d 2 C with ad − bc = 1 and z 2 C [ f1g. As is well known, a M¨obiustransformation maps circles in C^ to circles in C^, preserving angles between them.