Republic of Kenya Giraffe Conservation Status Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROFILES of ATTRACTION SITES-ELGEYO MARAKWET. Tourist Attractions in Elgeyo Marakwet County Include Sports Tourism, Rivers, a Na

PROFILES OF ATTRACTION SITES-ELGEYO MARAKWET. Tourist attractions in Elgeyo Marakwet County include Sports Tourism, Rivers, A national reserve, waterfalls and the hills and escarpments. Rimoi National Reserve The National Reserve is a protected area in the kerio valley along the escarpment of the Great Rift Valley. The 66 square kilometers (25sq mi) reserve was created in 1983 and is managed by the Kenya Wildlife Service. The isolated Kerio Valley lies between the Cherangani Hills and the Tugen Hills with the Elgeyo Escarpment rising more than 1,830 meters (6,000ft) above the valley in places. The valley is 4,000 feet (1,200m) deep. It has semi-tropical vegetation on the slopes, while the floor of the valley is covered by dry thorn bush. The most comfortable time of the year is in July and August when the rains have ended and the temperatures are not excessive. The reserve is on the west side of the Kerio River, while the Lake Kamnarok National Reserve is on the east side. The reserve has beautiful scenery, prolific birdlife and camping site in the bush beside Lake Kamnarok. Gazzement of the conservation area was done to protect wildlife from rampant poaching which was going on at the time. A fence was also put up to address human wildlife conflicts. It provides unique geological scenery & biodiversity and is one of the few protected areas within the spectacular Kerio Valley. The main attraction is the groups of elephants, Culture and scenery of the Kerio valley. The Reserve has earth and gravel road network which make for an adventurous outing. -

Conserving Wildlife in African Landscapes Kenya’S Ewaso Ecosystem

Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press smithsonian contributions to zoology • number 632 Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press AConserving Chronology Wildlife of Middlein African Missouri Landscapes Plains Kenya’sVillage Ewaso SitesEcosystem Edited by NicholasBy Craig J. M. Georgiadis Johnson with contributions by Stanley A. Ahler, Herbert Haas, and Georges Bonani SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of “diffusing knowledge” was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the Institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: “It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge.” This theme of basic research has been adhered to through the years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, com- mencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to History and Technology Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Museum Conservation Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report on the research and collections of its various museums and bureaus. The Smithsonian Contributions Series are distributed via mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institu- tions throughout the world. Manuscripts submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press from authors with direct affilia- tion with the various Smithsonian museums or bureaus and are subject to peer review and review for compliance with manuscript preparation guidelines. -

Heartland News May - August 2009 © AWF

African Heartland News May - August 2009 © AWF A NEWSLETTER FOR PARTNERS OF THE AFRICAN WILDLIFE FOUNDATION IN THIS ISSUE Opening of Conservation Science Centre in Lomako Yokokala Reserve, DRC TOP STORY: Lomako Conservation Science Centre In one of the earlier editions of this USAID’s Central Africa Program for the newsletter, we reported exciting news Environment (CARPE); the Ambassador about AWF's support to the Congolese of Canada; and partners from the Institute for Nature Conservation (ICCN) tourism industry. to establish the Lomako Yokokala Faunal Reserve in the Democratic Republic of The centre has been developed to support the Congo. This Page 1 reserve was created © AWF s p e c i f i c a l l y t o protect equatorial rainforests and the LAND: Sinohydro Court Case rare bonobo (Pan paniscus). T h e bonobo, or pygmy c h i m p a n z e e , i s one of the most threatened of the world’s five great a p e s . A f t e r i t s e s t a b l i s h m e n t , Page 4 AW F e m b a r k e d o n s u p p o r t i n g ICCN to create capacity, systems ENTERPRISE: and infrastructure Linking Livestock to Markets Projects Main building at Science Center f o r e f f e c t i v e management of the reserve. Already, a Park Manager the conservation science program which has been posted to the reserve and will revitalize applied bonobo research guards recruited and trained to patrol and forest monitoring in the reserve. -

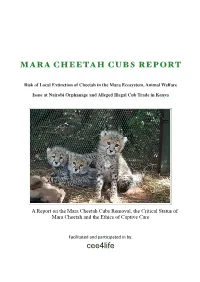

MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Cee4life

MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Risk of Local Extinction of Cheetah in the Mara Ecosystem, Animal Welfare Issue at Nairobi Orphanage and Alleged Illegal Cub Trade in Kenya A Report on the Mara Cheetah Cubs Removal, the Critical Status of Mara Cheetah and the Ethics of Captive Care Facilitated and par-cipated in by: cee4life MARA CHEETAH CUBS REPORT Risk of Local Extinction of Cheetah in the Mara Ecosystem, Animal Welfare Issue at Nairobi Orphanage and Alleged Illegal Cub Trade in Kenya Facilitated and par-cipated in by: cee4life.org Melbourne Victoria, Australia +61409522054 http://www.cee4life.org/ [email protected] 2 Contents Section 1 Introduction!!!!!!!! !!1.1 Location!!!!!!!!5 !!1.2 Methods!!!!!!!!5! Section 2 Cheetahs Status in Kenya!! ! ! ! ! !!2.1 Cheetah Status in Kenya!!!!!!5 !!2.2 Cheetah Status in the Masai Mara!!!!!6 !!2.3 Mara Cheetah Population Decline!!!!!7 Section 3 Mara Cub Rescue!! ! ! ! ! ! ! !!3.1 Abandoned Cub Rescue!!!!!!9 !!3.2 The Mother Cheetah!!!!!!10 !!3.3 Initial Capture & Protocols!!!!!!11 !!3.4 Rehabilitation Program Design!!!!!11 !!3.5 Human Habituation Issue!!!!!!13 Section 4 Mara Cub Removal!!!!!!! !!4.1 The Relocation of the Cubs Animal Orphanage!!!15! !!4.2 The Consequence of the Mara Cub Removal!!!!16 !!4.3 The Truth Behind the Mara Cub Removal!!!!16 !!4.4 Past Captive Cheetah Advocations!!!!!18 Section 5 Cheetah Rehabilitation!!!!!!! !!5.1 Captive Wild Release of Cheetahs!!!!!19 !!5.2 Historical Cases of Cheetah Rehabilitation!!!!19 !!5.3 Cheetah Rehabilitation in Kenya!!!!!20 Section 6 KWS Justifications -

KO RA N Ationalpark, Asako Village,Kenya

A B K George Adamson loved Kora as one of the last true y O T s wildernesses in Kenya. Inaccessible, thorny and o boiling hot as it was, it was ideal refuge for him, n a R y his lions and his ideals although he was under F k enormous pressure from Somali tribesmen, their i A t stock and their guns. Ultimately he fell to their z o j guns, but that was something we were both o h N prepared to accept for the privilege of the way of n v life there and what we were able to achieve. a i George desperately wanted me to continue his l t l work there and to make sure that all our efforts George Adamson’s camp, rebuilt by GAWPT a i had not been in vain. It was out of the question at o the time as the politics then were in disarray and I g n had taken on The Mkomazi Project in Tanzania in e George’s name, which was and still is a difficult a and time-consuming task with never an end in , sight. l K P Times have changed. Domestic stock is still a e problem in Kora with on going pastoral incursions. a n But the Kenya Wildlife Services (KWS) are r y determined to rehabilitate Kora as part of the k Meru conservation area. They have a multi- a , disciplinary approach to the problem and we are George Adamson at Kora 1987 . confident that they will make it work. Poaching of – Photographers International the large mammals has abated almost completely. -

Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary

BABILE ELEPHANT SANCTUARY MANAGEMENT PLAN December, 2010 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Wildlife for Sustainable Authority (EWCA) Development (WSD) Citation - EWCA and WSD (2010) Management Plan of Babile Elephant Sanctuary. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. 216pp. Acronyms AfESG - African Elephant Specialist Group BCZ - Biodiversity Conservation Zone BES - Babile Elephant Sanctuary BPR - Business Processes Reengineering CBD - Convention on Biological Diversity CBEM - Community Based Ecological Monitoring CBOs - Community Based Organizations CHA - Controlled Hunting Area CITES - Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora CMS - Convention on Migratory Species CSA - Central Statistics Agency CSE - Conservation Strategy of Ethiopia CUZ - Community Use Zone DAs - Development Agents DSE - German Foundation for International Development EIA - Environmental Impact Assessment EPA - Environmental Protection Authority EWA - Ethiopian Wildlife Association EWCA - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Authority EWCO - Ethiopian Wildlife Conservation Organization EWNHS - Ethiopian Wildlife and Natural History Society FfE - Forum for Environment GDP - Gross Domestic Product GIS - Geographic Information System ii GPS - Global Positioning System HEC – Human-Elephant Conflict HQ - Headquarters HWC - Human-Wildlife Conflict IBC - Institute of Biodiversity Conservation IRUZ - Integrated Resource Use Zone IUCN - International Union for the Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources KEAs - Key Ecological Targets -

The Status of Kenya's Elephants

The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 C. Thouless, J. King, P. Omondi, P. Kahumbu, I. Douglas-Hamilton The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 © 2008 Save the Elephants Save the Elephants PO Box 54667 – 00200 Nairobi, Kenya first published 2008 edited by Helen van Houten and Dali Mwagore maps by Clair Geddes Mathews and Philip Miyare layout by Support to Development Communication CONTENTS Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations iv Executive summary v Map of Kenya viii 1. Introduction 1 2. Survey techniques 4 3. Data collection for this report 7 4. Tsavo 10 5. Amboseli 17 6. Mara 22 7. Laikipia–Samburu 28 8. Meru 36 9. Mwea 41 10. Mt Kenya (including Imenti Forest) 42 11. Aberdares 47 12. Mau 51 13. Mt Elgon 52 14. Marsabit 54 15. Nasolot–South Turkana–Rimoi–Kamnarok 58 16. Shimba Hills 62 17. Kilifi District (including Arabuko-Sokoke) 67 18. Northern (Wajir, Moyale, Mandera) 70 19. Eastern (Lamu, Garissa, Tana River) 72 20. North-western (around Lokichokio) 74 Bibliography 75 Annexes 83 The status of Kenya’s elephants 1990–2002 AcKnowledgemenTs This report is the product of collaboration between Save the Elephants and Kenya Wildlife Service. We are grateful to the directors of KWS in 2002, Nehemiah Rotich and Joseph Kioko, and the deputy director of security at that time, Abdul Bashir, for their support. Many people have contributed to this report and we are extremely grateful to them for their input. In particular we would like to thank KWS field personnel, too numerous to mention by name, who facilitated our access to field records and provided vital information and insight into the status of elephants in their respective areas. -

Download List of Physical Locations of Constituency Offices

INDEPENDENT ELECTORAL AND BOUNDARIES COMMISSION PHYSICAL LOCATIONS OF CONSTITUENCY OFFICES IN KENYA County Constituency Constituency Name Office Location Most Conspicuous Landmark Estimated Distance From The Land Code Mark To Constituency Office Mombasa 001 Changamwe Changamwe At The Fire Station Changamwe Fire Station Mombasa 002 Jomvu Mkindani At The Ap Post Mkindani Ap Post Mombasa 003 Kisauni Along Dr. Felix Mandi Avenue,Behind The District H/Q Kisauni, District H/Q Bamburi Mtamboni. Mombasa 004 Nyali Links Road West Bank Villa Mamba Village Mombasa 005 Likoni Likoni School For The Blind Likoni Police Station Mombasa 006 Mvita Baluchi Complex Central Ploice Station Kwale 007 Msambweni Msambweni Youth Office Kwale 008 Lunga Lunga Opposite Lunga Lunga Matatu Stage On The Main Road To Tanzania Lunga Lunga Petrol Station Kwale 009 Matuga Opposite Kwale County Government Office Ministry Of Finance Office Kwale County Kwale 010 Kinango Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Floor,At Junction Off- Kinango Town,Next To Ministry Of Lands 1st Kinango Ndavaya Road Floor,At Junction Off-Kinango Ndavaya Road Kilifi 011 Kilifi North Next To County Commissioners Office Kilifi Bridge 500m Kilifi 012 Kilifi South Opposite Co-Operative Bank Mtwapa Police Station 1 Km Kilifi 013 Kaloleni Opposite St John Ack Church St. Johns Ack Church 100m Kilifi 014 Rabai Rabai District Hqs Kombeni Girls Sec School 500 M (0.5 Km) Kilifi 015 Ganze Ganze Commissioners Sub County Office Ganze 500m Kilifi 016 Malindi Opposite Malindi Law Court Malindi Law Court 30m Kilifi 017 Magarini Near Mwembe Resort Catholic Institute 300m Tana River 018 Garsen Garsen Behind Methodist Church Methodist Church 100m Tana River 019 Galole Hola Town Tana River 1 Km Tana River 020 Bura Bura Irrigation Scheme Bura Irrigation Scheme Lamu 021 Lamu East Faza Town Registration Of Persons Office 100 Metres Lamu 022 Lamu West Mokowe Cooperative Building Police Post 100 M. -

G4S OFFICES 1 ABC Place Total Petrol Station 2 Airport JKIA Outside

G4S OFFICES NAIROBI OFFICES 1 ABC Place Total petrol Station 2 Airport JKIA Outside Cargo Center 3 Nairobi Safari Club Nairobi Safari Club parking 4 Athiriver Chaster acade-Opp Athiriver Mining 5 Buruburu Buruburu Shoping centre -Next to Tuskys 6 Kampus Mall University Way Opp UNO 7 Afya center Oillibya petro station Opp Afya Center 8 Moi Avenue Moi Avenue Private packing next to Equity Bank 9 Koinange street Koinange street Private packing Opp Chai house 10 Standard Street Opp CBA Bank 11 Hilton Acade Hilton Acade-Office1 12 Hilton Acade Hilton Acade-Office2 13 Community Community Area Opp Ministry of Public Works 14 Karen Shell Petrol Station Opp Karen Police Station 15 Dagoreti Total petrol Station 16 Hurlingh Hurligurm at Kenol Petrol Station 17 Industrial Area Enterprise Road at Likoni Junction Total Petrol Station 18 Kiambu Diana House,First Floor Next to Fred Pharmacy 19 Kirinyaga Road Kirinyanga Road Opp Shell Petrol 20 Kitengela KENOL KOBIL PETROL STATION -PIZZA INN 21 Limuru Road Limuru Road Total Petrol Station next to Aga khan primary school 22 Embakasi Hub North Airport Road Opp Taj Mall 23 City Branch Mawa Court Opp Mburungar 24 Ngong Ngong Centre Opp Naivas Supermarket 25 Riverside Riverside drive -German Embassy 26 Rongai Kobil Petrol Station 27 UN-Gigiri Kobil Petrol Station Next to Java 28 Westlands Near the Mall At Shell Petrol station 29 Willson Airport Opp Shell petrol Station 30 Witu Rd Next to Toyota Ltd,DHL offices 31 Survey-Shell Chomazone Shell Petrol station Survey Thika Road 32 Thome Shell Petrol Station -Thika -

The Plains of Africa

WGCU Explorers presents… The Plains of Africa Kenya Wildlife Safari with Optional 1-Night Nairobi with Elephant Orphanage Pre Tour Extension with Optional 4-Night Tanzania Post Tour Extension September 6 – 19, 2018 See Back Cover Book Now & Save $100 Per Person For more information contact Liz Novak • Monique Benoit Stewart Travel Service Inc. (239) 591-8183 [email protected] or [email protected] Small Group Travel rewards travelers with new perspectives. With just 12-24 passengers, these are the personal adventures that today's cultural explorers dream of. 14 Days ● 33 Meals: 12 Breakfasts, 11 Lunches, 10 Dinners Book Now & Save $100 Per Person: pp *pp Double $7,859 Double $7,759 For bookings made after Feb 07, 2018 call for rates. Included in Price: Round Trip Air from Regional Southwest Airport, Air Taxes and Fees/Surcharges, Attraction Taxes and Fees, Hotel Transfers, Group Round Trip Transfer from WGCU to and from RSW Airport Not included in price: Cancellation Waiver and Insurance of $360 per person, Visa, Park Fees * All Rates are Per Person and are subject to change, based on air inclusive package from RSW Upgrade your in-flight experience with Elite Airfare Additional rate of: Business Class $6,990 pp † Refer to the reservation form to choose your upgrade option IMPORTANT CONDITIONS: Your price is subject to increase prior to the time you make full payment. Your price is not subject to increase after you make full payment, except for charges resulting from increases in government-imposed taxes or fees. Once deposited, you have 7 days to send us written consumer consent or withdraw consent and receive a full refund. -

Aprp 2011/2012 Fy

KENYA ROADS BOARD ANNUAL PUBLIC ROADS PROGRAMME FY 2011/ 2012 Kenya Roads Board (KRB) is a State Corporation established under the Kenya Roads Board Act, 1999. Its mandate is to oversee the road network in Kenya and coordinate its development, rehabilitation and maintenance funded by the KRB Fund and to advise the Minister for Roads on all matters related thereto. Our Vision An Effective road network through the best managed fund Our Mission Our mission is to fund and oversee road maintenance, rehabilitation and development through prudent sourcing and utilisation of resources KRB FUND KRB Fund comprises of the Road Maintenance Levy, Transit Toll and Agricultural cess. Fuel levy was established in 1993 by the Road Maintenance Levy Act. Fuel levy is charged at the rate of Kshs 9 per litre of petrol and diesel. The allocation as per the Kenya Roads Board Act is as follows: % Allocation Roads Funded Agency 40% Class A, B and C KENHA 22% Constituency Roads KERRA 10% Critical links – rural roads KERRA 15% Urban Roads KURA 1% National parks/reserves Kenya Wildlife Service 2% Administration Kenya Roads Board 10% Roads under Road Sector Investment Programme KRB/Minister for Roads KENYA ROADS BOARD FOREWORD This Annual Public Roads Programme (APRP) for the Financial Year (FY) 2011/2012 continues to reflect the modest economic growth in the country and consequently minimal growth in KRBF. The Government developed and adopted Vision 2030 which identifies infrastructure as a key enabler for achievement of its objective of making Kenya a middle income country by 2030. The APRP seeks to meet the objectives of Vision 2030 through prudent fund management and provision of an optimal improvement of the road network conditions using timely and technically sound intervention programmes. -

ITEN MUNICIPALITY Athletics Capital of the World

ITEN MUNICIPALITY Athletics Capital of the World INTERGRATED DEVELOPMENT PLAN 2019 - 2023 Athletic capital of the world VISION A town of choice for Sports, Tourism and Investment MISSION To transform the delivery of services by ensuring equitable access, development and excellence at all levels and harness the socio- economic contributions that can create a liveable environment for all residents. Contents FOREWORD ................................................................................................................................................... v ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ................................................................................................................................. vi CHAPTER ONE ............................................................................................................................................... 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ..................................................................................................................... 1 Physical and topography ...................................................................................................................... 1 Ecological conditions ............................................................................................................................ 1 Climatic conditions ............................................................................................................................... 2 Administrative units ................................................................................................................................