Arabic-English-Arabic Translation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Reference List Construction and Industry

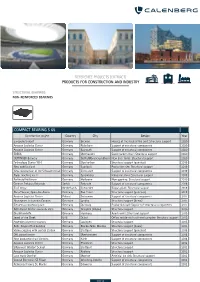

REFERENCE PROJECTS (EXTRACT) PRODUCTS FOR CONSTRUCTION AND INDUSTRY STRUCTURAL BEARINGS NON-REINFORCED BEARINGS COMPACT BEARING S 65 Construction project Country City Design Year Europahafenkopf Germany Bremen Houses at the head of the port: Structural support 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Paderborn Support of structural components 2020 Amazon Logistics Center Germany Bayreuth Support of structural components 2020 EDEKA Germany Oberhausen Supermarket chain: Structural support 2020 OETTINGER Brewery Germany Gotha/Mönchengladbach New beer tanks: Structural support 2020 Technology Center YG-1 Germany Oberkochen Structural support (punctual) 2019 New nobilia plant Germany Saarlouis Production site: Structural support 2019 New construction of the Schwaketenbad Germany Constance Support of structural components 2019 Paper machine no. 2 Germany Spremberg Industrial plant: Structural support 2019 Parkhotel Heilbronn Germany Heilbronn New opening: Structural support 2019 German Embassy Belgrade Serbia Belgrade Support of structural components 2018 Bio Energy Netherlands Coevorden Biogas plant: Structural support 2018 NaturTheater, Open-Air-Arena Germany Bad Elster Structural support (punctual) 2018 Amazon Logistics Center Poland Sosnowiec Support of structural components 2017 Novozymes Innovation Campus Denmark Lyngby Structural support (linear) 2017 Siemens compressor plant Germany Duisburg Production hall: Support of structural components 2017 DAV Alpine Centre swoboda alpin Germany Kempten (Allgäu) Structural support 2016 Glasbläserhöfe -

VENTURING INTO OUR PAST NEWSLETTER of the JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY of the CONEJO VALLEY and VENTURA COUNTY (JGSCV) Volume 4, Issue 5 February 2009

VENTURING INTO OUR PAST NEWSLETTER OF THE JEWISH GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY OF THE CONEJO VALLEY AND VENTURA COUNTY (JGSCV) Volume 4, Issue 5 February 2009 President's Letter There was laughter while learning at Ron Aron's presentation at the January 4 meeting "The Musical 'Chicago' and All That Genealogical Jazz"! Ron is a four-time guest speaker, each time with a different presentation that has the audience learning while enjoying the tales he tells. This presentation, part of a program given at the 2008 IAJGS International Conference on Jewish Genealogy, demonstrated through a myriad of internet resources, newspaper and court documents the truth from fiction about Belva Gaertner, one of the two real-life women who were convicted of murdering their lovers in Chicago in 1924. The websites and references referred to by Ron is posted on www.JGSCV.org website under programs, previous, and the January 4, 2009 date. Recepients of this Newsletter who have not yet joined our JGSCV for the year 2009 are so encouraged. What better can you do to spend $25/$30 for socialization, fun, education and meeting new friends! Additional contributions to our library and program funds are greatly appreciated. As a non-profit organization your SPEAKER RON ARONS contributions are eligible for tax deductibility. We met last Nov. & Dec. on Monday evenings. Some members may prefer the Sunday afternoon meetings. The board is considering holding 2-3 meetings a year on a weekday evening. We would like to hear from members if they would have problems with such a plan. The majority of meetings would still be on Sunday afternoons. -

E-Book Readers Kindle Sony and Nook a Comparative Study

E-BOOK READERS KINDLE SONY AND NOOK: A COMPARATIVE STUDY Baban Kumbhar Librarian Rayat Shikshan Sanstha’s Dada Patil Mahavidyalaya, Karjat, Dist Ahmednagar E-mail:[email protected] Abstract An e-book reader is a portable electronic device for reading digital books and periodicals, better known as e- books. An e-book reader is similar in form to a tablet computer. Kindle is a series of e-book readers designed and marketed by Amazon.com. The Sony Reader was a line of e-book readers manufactured by Sony. NOOK is a brand of e-readers developed by American book retailer Barnes & Noble. Researcher compares three E-book readers in the paper. Keywords: e-book reader, Kindle, Sony, Nook 1. Introduction: An e-reader, also called an e-book reader or e-book device, is a mobile electronic device that is designed primarily for the purpose of reading digital e-books and periodicals. Any device that can display text on a screen may act as an e-book reader, but specialized e-book reader designs may optimize portability, readability (especially in sunlight), and battery life for this purpose. A single e-book reader is capable of holding the digital equivalent of hundreds of printed texts with no added bulk or measurable mass.[1] An e-book reader is similar in form to a tablet computer. A tablet computer typically has a faster screen capable of higher refresh rates which makes it more suitable for interaction. Tablet computers also are more versatile, allowing one to consume multiple types of content, as well as create it. -

DUBAI Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide

DUBAI Cushman & Wakefield Global Cities Retail Guide Cushman & Wakefield | Dubai | 2019 0 Dubai has developed into the retail hub of the Middle East and is the most sophisticated retail market in the region. The proliferation of retail development over the last ten years has led to Dubai having one of the highest retail to population densities in the world. It finished ahead of New York and London for shopping in TripAdvisor’s recently published second annual Cities Survey. Perhaps the best known of Dubai’s plentiful selection of retail malls is The Dubai Mall which is located in the heart of the prestigious Downtown Dubai and is one of the world’s most-visited retail and entertainment destination, having welcomed more than 80 million visitors annually over the last five years. Dubai Mall provides over 1,350 retail stores and over 200 food and beverage outlets, together with leisure and entertainment attractions. Its most recent expansion in 2017 provides connectivity to the attractions and amenities in the neighbouring Burj Khalifa. Other high- profile retail malls that dominate the retail market include Mall of the Emirates and Dubai Festival City. International retail brands are predominantly operated under license by ‘retail partners’ who hold licenses for multiple brands in their portfolios. These include groups such as Al Shaya, Landmark and Majid Al Futtaim. Often these retail operators can also be mall developers in their own right. These companies are very powerful in the retail sector and can make the difference between a new mall development securing attractive brands or struggling to attract the right brands and potential failure. -

MEET US at GULFOOD 21-25 FEBRUARY We Invite You Ali Group Offers to Discover the Widest Range Our Brands

MEET US Ali Group offers the widest range AT GULFOOD of innovative, cost-saving 21-25 FEBRUARY Photo: Subbotina Anna / Shutterstock.com and eco-friendly products in the foodservice equipment industry. 2016 We invite you to discover our brands. Click here to see where our brands are located Gulfood venue map and opening times Dubai Metro FIND OUR BRANDS ZA’ABEEL HALL 4 ZA’ABEEL HALL 5 ZA’ABEEL HALL 6 HALL 2 Booth Z4-A60 Booth Z5-C38 Booth Z6-A29 Booth B2-18 Booth Z4-A76 Booth Z6-A62 Booth B2-39 Booth Z6-C55 Booth Z4-C8 Booth Z6-E8 Booth Z4-C82 Booth Z5-D8 Booth Z4-F60 Booth Z5-D32 Booth Z4-G28 Booth Z5-D60 VENUE MAP OPENING TIMES 21 February 11am - 7pm 22 February 11am - 7pm 21 - 25 February 2016 23 February 11am - 7pm Dubai World Trade Centre 24 February 11am - 7pm www.gulfood.com 25 February 11am - 5pm Convention Tower CONVENTION GATE For any further information P A VILION HALL SHEIKH ZA’ABEEL NEW HALLS MAKTOUM please visit: HALL 8 HALL ZA’ABEEL www.gulfood.com PLAZA HALL 7 SHEIKH ZA’ABEEL HALL RASHID HALL HALL 6 HALL 5 HALL 1 HALL 2 HALL 3 HALL 4 4A EXHIBITION GATE Ibis Hotel TRADE CENTRE ARENA & SHEIKH SAEED HALLS HALL 9 FOOD AND DRINK BEVERAGE & BEVERAGE EQUIPMENT RESTAURANT & CAFÉ FOODSERVICE EQUIPMENT SALON CULINAIRE REGISTRATION AREAS DUBAI METRO The Dubai Metro’s red line ‘World Trade Centre Station’ serves the exhibition centre. Burj Khalifa/Dubai Mall Jumeirah Lake Towers METRO OPERATIONS HOURS Mall of the Emirates World Trade Centre Trade World Al Ras Palm Deira Dubai Internet City Noor Islamic Bank Financial Center Emirates -

Delivering a Sustainable Expo

DELIVERING A SUSTAINABLE EXPO Expo 2020 Dubai Sustainability Report 2018 “We pay the utmost care and attention to our environment for it is an integral part of the country, our history and our heritage. Our forefathers and our ancestors lived in this land and coexisted with its environment, on land and sea, and instinctively realised the need to preserve it.” LATE SHEIKH ZAYED BIN SULTAN AL NAHYAN Founder of the UAE “Protection of the environment and achievement of sustainable development in the UAE is a national duty; it has its own institutional structures, integrated legislature and advanced systems.” HIS HIGHNESS SHEIKH KHALIFA BIN ZAYED AL NAHYAN President of the United Arab Emirates “We are building a new reality for our people, a new future for our children, and a new model of development.” HIS HIGHNESS SHEIKH MOHAMMED BIN RASHID AL MAKTOUM Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE and Ruler of Dubai “The civilised, advanced nation we seek to build and the sustainable development we are keen to achieve both require concerted efforts from all sectors of the community and from all public and private entities and organisations. They require consistent and harmonious work in order to achieve our goals and promote and underpin our nation’s status with its distinct role regionally and internationally.” HIS HIGHNESS SHEIKH MOHAMED BIN ZAYED AL NAHYAN Crown Prince of Abu Dhabi and Deputy Supreme Commander of UAE Armed Forces INTRODUCTION HIS HIGHNESS SHEIKH AHMED BIN SAEED AL MAKTOUM President, Dubai Civil Aviation Authority Chairman of the Expo Dubai 2020 Higher Committee It gives me great pleasure to introduce the first Expo 2020 Dubai Sustainability Report (2018) as we build up to the World Expo in 2020. -

Rta Bus Routes List 2019

Dubai Bus ﻻﺋﺤﺔ ﺧﻄﻮط اﻟﺤﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ ﻳﻨﺎﻳﺮ ٢٠١٩ Bus Route Service List January 2019 رﻗﻢ اﻟﺨﻂ ﻳﻨﻄﻠﻖ ﻣﻦ ﻳﺼﻞ ﻟﻐﺎﻳﺔ رﻗﻢ اﻟﺨﻂ ﻳﻨﻄﻠﻖ ﻣﻦ ﻳﺼﻞ ﻟﻐﺎﻳﺔ Route ID Start from End - to Route ID Start from End - to اﻟﺨﻄﻮط اﻟﺴﻳﻌﺔ اﻟﺨﻄﻮط اﻟﻌﺎﻣﺔ Express Bus Routes Local Bus Routes 13B ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ 7 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﺴﻄﻮة اﻟﻘﻮز ﺟﻲ ﻣﺎرت 13B Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Qusais Bus Stn 7 Al Satwa Bus Stn Al Quoz, J Mart 91A ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺟﺒﻞ ﻋ 8 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو اﺑﻦ ﺑﻄﻮﻃﺔ 91A Gold Souq Bus Stn Jebel Ali Bus Stn 8 Gold Souq Bus Stn Ibn Battuta MS X02 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ اﻟﺴﻄﻮة ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﻌﺒﺮ اﻟﺨﻠﻴﺞ اﻟﺘﺠﺎري X02 Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Al Satwa 9 Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Business Bay MS 9 X13 ﻗﻳﺔ اﻟﻠﻮﻟﻮ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﺴﻄﻮة 10 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﻮز X13 LuLu Village Al Satwa Bus Stn 10 Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Quoz Bus Stn X22 ﻣﻨﻄﻘﺔ اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ اﻟﺼﻨﺎﻋﻴﺔ 2 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﻌﺒﺮ اﻟﺨﻠﻴﺞ اﻟﺘﺠﺎري 11A ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻌﻮﻳﺮ X22 Al Qusais Ind'l Area 2 Business Bay MS 11A Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Awir X23 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻤﺪﻳﻨﺔ اﻟﻌﺎﻟﻤﻴﺔ 11B ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو اﻟﺮاﺷﺪﻳﺔ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ اﻟﻌﻮﻳﺮ 11B Rashidiya MS Al Awir Terminus X23 Gold Souq Bus Stn International City ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻐﺒﻴﺒﺔ X25 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻜﺮاﻣﺔ د ﻟﻠﺘﻌﻬﻴﺪ, ﺑﻨﻚ أﺳﻜﺘﻠﻨﺪا اﻟﻤﻠﻜﻲ 2 12 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﻮز Al Ghubaiba Bus Stn Al Quoz Bus Stn 12 X25 Al Karama Bus Stn Dubai Outsourcing 13 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ ﻣﺴﺎﻛﻦ اﻟﻌﻤﺎل Gold Souq Bus Stn Al Qusais DM Housing X28 ﻗﻳﺔ اﻟﻠﻮﻟﻮ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﻣﺘﺮو ﻣﺪﻳﻨﺔ د ﻟﻼﻧﺘﺮﻧﺖ LuLu Village Dubai Internet City MS 13 ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت ﺳﻮق اﻟﺬﻫﺐ ﻣﺤﻄﺔ ﺣﺎﻓﻼت اﻟﻘﺼﻴﺺ X28 13A -

Hana Biosciences

JOURNAL OF APPLIED CASE RESEARCH JACR Volume 8, Number 1, 2009 Table of Contents Editors and Reviewers .....................................................................................................ii Notes To Authors .......................................................................................................... iii Letter From The Editor ................................................................................................... iv Going for Growth at Gecko Press .................................................................................... 1 ABC Communications, Inc. ........................................................................................... 25 Adult Day Care, Inc....................................................................................................... 36 Rebuilt To Last: An Organizational Change Initiative ................................................... 51 Setting a Course for Tissue Repair: Mesynthes .............................................................. 62 Hewlett Packard: Rethinking the Rethinking of HP ...................................................... 78 i Editors and Reviewers The Journal appreciates the time and commitment of all those who generously give their time in reviewing and editing manuscripts. The following are those who have assisted in this volume. Reviewer names are forthcoming. PREVIOUS EDITORS OF JACR Carl Ruthstrom, University of Houston-Downtown Dan Jennings, Texas A&M University Leslie Toombs, University of Texas at San Antonio Alex Sharland, -

Corpus Studies in Applied Linguistics

106 Pietilä, P. & O-P. Salo (eds.) 1999. Multiple Languages – Multiple Perspectives. AFinLA Yearbook 1999. Publications de l’Association Finlandaise de Linguistique Appliquée 57. pp. 105–134. CORPUS STUDIES IN APPLIED LINGUISTICS Kay Wikberg, University of Oslo Stig Johansson, University of Oslo Anna-Brita Stenström, University of Bergen Tuija Virtanen, University of Växjö Three samples of corpora and corpus-based research of great interest to applied linguistics are presented in this paper. The first is the Bergen Corpus of London Teenage Language, a project which has already resulted in a number of investigations of how young Londoners use their language. It has also given rise to a related Nordic project, UNO, and to the project EVA, which aims at developing material for assessing the English proficiency of pupils in the compulsory school system in Norway. The second corpus is the English-Norwegian Parallel Corpus (Oslo), which has provided data for both contrastive studies and the study of translationese. Altogether it consists of about 2.6 million words and now also includes translations of English texts into German, Dutch and Portuguese. The third corpus, the International Corpus of Learner English, is a collection of advanced EFL essays written by learners representing 15 different mother tongues. By comparing linguistic features in the various subcorpora it is possible to find out about non-nativeness generally and about problems shared by students representing different languages. 1 INTRODUCTION 1.1 Corpus studies and descriptive linguistics Corpus-based language research has now been with us for more than 20 years. The number of recent books dealing with corpus studies (cf. -

Download (237Kb)

CHAPTER II REVIEW OF RELATED LITERATURE In this chapter, the researcher presents the result of reviewing related literature which covers Corpus based analysis, children short stories, verbs, and the previous studies. A. Corpus Based Analysis in Children Short Stories In these last five decades the work that takes the concept of using corpus has been increased. Corpus, the plural forms are certainly called as corpora, refers to the collection of text, written or spoken, which is systematically gathered. A corpus can also be defined as a broad, principled set of naturally occurring examples of electronically stored languages (Bennet, 2010, p. 2). For such studies, corpus typically refers to a set of authentic machine-readable text that has been selected to describe or represent a condition or variety of a language (Grigaliuniene, 2013, p. 9). Likewise, Lindquist (2009) also believed that corpus is related to electronic. He claimed that corpus is a collection of texts stored on some kind of digital medium to be used by linguists for research purposes or by lexicographers in the production of dictionaries (Lindquist, 2009, p. 3). Nowadays, the word 'corpus' is almost often associated with the term 'electronic corpus,' which is a collection of texts stored on some kind of digital medium to be used by linguists for research purposes or by lexicographers for dictionaries. McCarthy (2004) also described corpus as a collection of written or spoken texts, typically stored in a computer database. We may infer from the above argument that computer has a crucial function in corpus (McCarthy, 2004, p. 1). In this regard, computers and software programs have allowed researchers to fairly quickly and cheaply capture, store and handle vast quantities of data. -

TAUS Speech-To-Speech Translation Technology Report March 2017

TAUS Speech-to-Speech Translation Technology Report March 2017 1 Authors: Mark Seligman, Alex Waibel, and Andrew Joscelyne Contributor: Anne Stoker COPYRIGHT © TAUS 2017 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system of any nature, or transmit- ted or made available in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of TAUS. TAUS will pursue copyright infringements. In spite of careful preparation and editing, this publication may contain errors and imperfections. Au- thors, editors, and TAUS do not accept responsibility for the consequences that may result thereof. Design: Anne-Maj van der Meer Published by TAUS BV, De Rijp, The Netherlands For further information, please email [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Introduction 4 A Note on Terminology 5 Past 6 Orientation: Speech Translation Issues 6 Present 17 Interviews 19 Future 42 Development of Current Trends 43 New Technology: The Neural Paradigm 48 References 51 Appendix: Survey Results 55 About the Authors 56 3 Introduction The dream of automatic speech-to-speech devices enabling on-the-spot exchanges using translation (S2ST), like that of automated trans- voice or text via smartphones – has helped lation in general, goes back to the origins of promote the vision of natural communication computing in the 1950s. Portable speech trans- on a globally connected planet: the ability to lation devices have been variously imagined speak to someone (or to a robot/chatbot) in as Star Trek’s “universal translator” to negoti- your language and be immediately understood ate extraterrestrial tongues, Douglas Adams’ in a foreign language. -

1. Introduction

This is the accepted manuscript of the chapter MacLeod, N, and Wright, D. (2020). Forensic Linguistics. In S. Adolphs and D. Knight (eds). Routledge Handbook of English Language and Digital Humanities. London: Routledge, pp. 360-377. Chapter 19 Forensic Linguistics 1. INTRODUCTION One area of applied linguistics in which there has been increasing trends in both (i) utilising technology to assist in the analysis of text and (ii) scrutinising digital data through the lens of traditional linguistic and discursive analytical methods, is that of forensic linguistics. Broadly defined, forensic linguistics is an application of linguistic theory and method to any point at which there is an interface between language and the law. The field is popularly viewed as comprising three main elements: (i) the (written) language of the law, (ii) the language of (spoken) legal processes, and (iii) language analysis as evidence or as an investigative tool. The intersection between digital approaches to language analysis and forensic linguistics discussed in this chapter resides in element (iii), the use of linguistic analysis as evidence or to assist in investigations. Forensic linguists might take instructions from police officers to provide assistance with criminal investigations, or from solicitors for either side preparing a prosecution or defence case in advance of a criminal trial. Alternatively, they may undertake work for parties involved in civil legal disputes. Forensic linguists often appear in court to provide their expert testimony as evidence for the side by which they were retained, though it should be kept in mind that standards here are required to be much higher than they are within investigatory enterprises.