Australian Inland Waters: a Limited Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sampling and Analysis of Lakes in the Corangamite CMA Region (2)

Sampling and analysis of lakes in the Corangamite CMA region (2) Report to the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority CCMA Project WLE/42-009: Client Report 4 Annette Barton, Andrew Herczeg, Jim Cox and Peter Dahlhaus CSIRO Land and Water Science Report xx/06 December 2006 Copyright and Disclaimer © 2006 CSIRO & Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. To the extent permitted by law, all rights are reserved and no part of this publication covered by copyright may be reproduced or copied in any form or by any means except with the written permission of CSIRO Land and Water or the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority. Important Disclaimer: CSIRO advises that the information contained in this publication comprises general statements based on scientific research. The reader is advised and needs to be aware that such information may be incomplete or unable to be used in any specific situation. No reliance or actions must therefore be made on that information without seeking prior expert professional, scientific and technical advice. To the extent permitted by law, CSIRO (including its employees and consultants) excludes all liability to any person for any consequences, including but not limited to all losses, damages, costs, expenses and any other compensation, arising directly or indirectly from using this publication (in part or in whole) and any information or material contained in it. From CSIRO Land and Water Description: Rocks encrusted with salt crystals in hyper-saline Lake Weering. Photographer: Annette Barton © 2006 CSIRO ISSN: 1446-6171 Report Title Sampling and analysis of the lakes of the Corangamite CMA region Authors Dr Annette Barton 1, 2 Dr Andy Herczeg 1, 2 Dr Jim Cox 1, 2 Mr Peter Dahlhaus 3, 4 Affiliations/Misc 1. -

Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Management Statement

Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Management Statement Land Stewardship & Biodiversity Department of Sustainability and Environment May 2005 This Management Statement has been written by Hugh Robertson and James Fitzsimons for the Department of Sustainability and Environment, Victoria. This Statement fulfils obligations by the State of Victoria to the Commonwealth of Australia, which provided financial assistance for the purchase of this reserve under the National Reserve System program of the Natural Heritage Trust. ©The State of Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment 2005 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968. ISBN 1 74152 140 8 Disclaimer: This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Cover: Permanent wetland surrounded by Stony Knoll Shrubland, Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve (Photo: James Fitzsimons). Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve Objectives This Management Statement for the Dreeite Nature Conservation Reserve outlines the reserve’s natural values and the directions for its management in the short to long term. The overall operational management objective is: Maintain, and enhance where appropriate, the condition of the reserve while allowing natural processes of regeneration, disturbance and succession to occur and actively initiating these processes where required. Background and Context Reason for purchase Since the implementation of the National Reserve System Program (NRS) in 1992, all Australian states and territories have been working toward the development of a comprehensive, adequate and representative (CAR) system of protected areas. -

Corangamite Heritage Study Stage 2 Volume 3 Reviewed

CORANGAMITE HERITAGE STUDY STAGE 2 VOLUME 3 REVIEWED AND REVISED THEMATIC ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY Prepared for Corangamite Shire Council Samantha Westbrooke Ray Tonkin 13 Richards Street 179 Spensley St Coburg 3058 Clifton Hill 3068 ph 03 9354 3451 ph 03 9029 3687 mob 0417 537 413 mob 0408 313 721 [email protected] [email protected] INTRODUCTION This report comprises Volume 3 of the Corangamite Heritage Study (Stage 2) 2013 (the Study). The purpose of the Study is to complete the identification, assessment and documentation of places of post-contact cultural significance within Corangamite Shire, excluding the town of Camperdown (the study area) and to make recommendations for their future conservation. This volume contains the Reviewed and Revised Thematic Environmental History. It should be read in conjunction with Volumes 1 & 2 of the Study, which contain the following: • Volume 1. Overview, Methodology & Recommendations • Volume 2. Citations for Precincts, Individual Places and Cultural Landscapes This document was reviewed and revised by Ray Tonkin and Samantha Westbrooke in July 2013 as part of the completion of the Corangamite Heritage Study, Stage 2. This was a task required by the brief for the Stage 2 study and was designed to ensure that the findings of the Stage 2 study were incorporated into the final version of the Thematic Environmental History. The revision largely amounts to the addition of material to supplement certain themes and the addition of further examples of places that illustrate those themes. There has also been a significant re-formatting of the document. Most of the original version was presented in a landscape format. -

Corangamite Cma 2019-2020

ACORANGAMITEnnual CMAReport 2019-2020 Table of Contents SECTION 1 YEAR IN REVIEW 6 VISION, VALUES AND APPROACH 7 HIGHLIGHTS 11 REGIONAL CONTRIBUTION 12 COVID-19 13 ACHIEVEMENTS, OPERATIONAL PERFORMANCE AND KEY INITIATIVES 14 WATERWAYS 17 LAND 30 COAST 36 BIODIVERSITY 41 COMMUNITY 47 MAXIMISING NRM INVESTMENT IN THE REGION 54 SECTION 2 OUR ORGANISATION, COMPLIANCE AND DISCLOSURES 61 OUR ORGANISATION 62 COMPLIANCE AND DISCLOSURES 67 SUMMARY OF FINANCIAL RESULTS 73 OFFICE-BASED ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACTS 76 SECTION 3 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 78 HOW THIS REPORT IS STRUCTURED 81 DECLARATION IN THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 82 COMPREHENSIVE OPERATING STATEMENT 83 BALANCE SHEET 84 CASH FLOW STATEMENT 85 STATEMENT OF CHANGES IN EQUITY 86 NOTES TO THE FINANCIAL STATEMENTS 87 SECTION 4 APPENDICES - KEY PERFORMANCE INDICATORS 127 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF COUNTRY The Corangamite Catchment Management Authority works on the lands, waters and seas of the Wadawurrung and Eastern Maar people and acknowledges them as Traditional Owners. It recognises and respects the diversity of their cultures and the deep connections they have with Country. It values partnerships with communities and organisations to improve the health of Indigenous people and Country. The Corangamite CMA Board and staff pay their respect to Elders, past and present, and acknowledge and recognise the primacy of Traditional Owners’ obligations, rights and responsibilities to use and care for their traditional lands, water and sea. CHAIRMAN AND CEO FOREWORD It is with pleasure that we present the Corangamite Catchment Other achievements include supporting over 183 km of fencing, Management Authority (CMA) 2019-20 Annual Report. nearly 28,001 ha of weed control and property management plans covering 10,572 ha. -

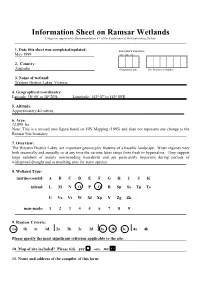

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories Approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties

Information Sheet on Ramsar Wetlands Categories approved by Recommendation 4.7 of the Conference of the Contracting Parties. 1. Date this sheet was completed/updated: FOR OFFICE USE ONLY. May 1999 DD MM YY 2. Country: Australia Designation date Site Reference Number 3. Name of wetland: Western District Lakes, Victoria 4. Geographical coordinates: Latitude: 380 00' to 380 20'S; Longitude: 1430 07' to 1430 55'E 5. Altitude: Approximately 40 metres. 6. Area: 32,898 ha Note: This is a revised area figure based on GIS Mapping (1995) and does not represent any change to the Ramsar Site boundary. 7. Overview: The Western District Lakes, are important geomorphic features of a basaltic landscape. Water regimes vary both seasonally and annually so at any time the various lakes range from fresh to hypersaline. They support large numbers of mainly non-breeding waterbirds and are particularly important during periods of widespread drought and as moulting sites for some species. 8. Wetland Type: marine-coastal: A B C D E F G H I J K inland: L M N O P Q R Sp Ss Tp Ts U Va Vt W Xf Xp Y Zg Zk man-made: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 9. Ramsar Criteria: 1a 1b 1c 1d 2a 2b 2c 2d 3a 3b 3c 4a 4b Please specify the most significant criterion applicable to the site: 10. Map of site included? Please tick yes -or- no.⌧ 11. Name and address of the compiler of this form: Simon Casanelia Parks Victoria 378 Cotham Road Kew VIC 3101 Australia Telephone 613 9816 1163 Facsimile 613 9816 9799 12. -

A Review of Historic Western Victorian Lake Conditions in Relation to Fish Deaths

A REVIEW OF HISTORIC WESTERN VICTORIAN LAKE CONDITIONS IN RELATION TO FISH DEATHS Publication 1108 March 2007 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Eel deaths occurred in waterways across Victoria from 2004 to 2006. EPA Victoria worked with responsible agencies to investigate the cause of the deaths. An information gap was identified regarding changes throughout the catchments over time. Much of this knowledge had not been documented formally and was difficult to assess. It is important to note that this report is based on a number of published accounts of the historical timeline as well as utilising personal accounts of history. Therefore there may be small discrepancies in exact dates. Anecdotal evidence and unpublished reports of the history of lakes Modewarre, Bolac and Colac indicate that, over the past 150 years, all lakes in the Western District have shown a distinct pattern of drying out during periods of extended drought. As early as 1846 the lakes showed signs of drying, which would indicate that any fish within those lakes also died due to lack of good quality water. The three lakes examined have been stocked by landholders, recreational anglers or commercial eel fishermen to hold the current stock of fish and eels. The catchments in which each lake sits have undergone changes, including culverts being developed to reduce flooding, the size of water storage reservoirs being increased and changes in agricultural practices. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS EPA would like to formally acknowledge the contribution of all those who assisted with the research into the Western District lakes. Much information was held in the minds of those who visit the lakes regularly for recreation, farming and lifestyle, and it is this that has provided such broad insight into one of Victoria’s precious resources. -

Western District Lakes

Western District Lakes MAINLAND ISLAND CHARACTERISTICS Jurisdiction Victoria Corangamite NRM Regions Glenelg Hopkins Colac Otway, Corangamite, LGAs Golden Plains, Surf Coast Size 226, 000 hectares Inland aquatic: freshwater, salt lakes, Dominant Type lagoons Crown Land Land Tenure Agriculture Overall Conservation Threat Small areas of Wildlife Reserves Priority Value Status Land use Surrounding Issues Weed density Very High Very High Very High Pest denisty Key biodiversity and conservation values of WESTERN DISTRICT LAKES . 28 threatened species . 1 threatened community . 7 migratory species Key Biodiversity . Very high species richness Values . Very high endemism . Western District Lakes Ramsar wetland . 15 nationally important aquatic ecosystems . Native vegetation present . Vertebrate pest species present CONSERVATION VALUE THREAT STATUS Categories Ranks/Scores Categories Ranks/Scores 1 Biodiversity values Very High (16) 1 Density of pest species Very High (8) 2 Uniqueness Very High (4) 2 Pest impact level High 6 3 Representativeness Very High (4) 3 Invasion fronts/range boundaries High (3) 4 Adjacency Very High (4) 4 Land use risk Very High (5) 5 Area to perimeter ratio Very High (4) 5 Weed density High (3) 6 Area without statutory protection High (3) Key Threats and Impacts Pest Species Present or Potentially Present Cane toad Feral cat Feral pig Rodents Carp, European carp Feral deer Feral water buffalo Tilapia, Mozambique Tilapia Indian Myna, Common Weather loach; Oriental European red fox Feral donkey Myna weather loach Mosquito -

Challenging the Current Assumptions About Salinity Processes in the Corangamite Region, Australia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Federation ResearchOnline Beyond hydrogeologic evidence: challenging the current assumptions about salinity processes in the Corangamite region, Australia P. G. Dahlhaus & J. W. Cox & C. T. Simmons & C. M. Smitt Abstract In keeping with the standard scientific methods, evidence found which supports significant rises in ground- investigations of salinity processes focus on the collec- water following widespread land-use change. In many tion and interpretation of contemporary scientific data. areas, salinity is an inherent component of the region’s However, using multiple lines of evidence from non- landscapes, and sustains world-class environmental assets hydrogeologic sources such as geomorphic, archaeologi- that require appropriate salinity levels for their ecological cal and historical records can substantially add value to health. Managing salinity requires understanding the the scientific investigations. By using such evidence, the specific salinity processes in each landscape. validity of the assumptions about salinity processes in Australian landscapes is challenged, especially the Résumé En se conformant aux méthodes scientifiques assumption that the clearing of native vegetation has standard, les études de l’acquisition de la salinité se resulted in rising saline groundwater in all landscapes. concentrent sur la collecte et l’interprétation de données In the Corangamite region of south-west Victoria, scientifiques contemporaines. Toutefois, l’utilisation de salinity has been an episodic feature of the landscapes filières multiples de données provenant de sources non throughout the Quaternary and was present at the time hydrogéologiques telles que des compilations géomorpho- of the Aboriginal inhabitants and the first pastoral logiques, archéologiques et historiques peut ajouter de settlement by Europeans. -

ACCOMMODATION ADVERTISEMENTS (Later Years Omitted) Aireys Inlet, Vic

Bird Observer Index 1975-2011 A ACCOMMODATION ADVERTISEMENTS (later years omitted) Aireys Inlet, Vic. 1986/8.83, 9.95, 10.107, 11.113, 12.129; 1987/1.10, 3.22, 4.27, 5.41, 6.60, 7.63, 8.78, 8.80, 9.93, 10.105, 11.111, 12.129; 1988/2.22, 3.35, 4.47, 6.72, 8.88, 10.113, 12.144; 1989/1.12, 4.36, 6.59, 8.74, 11.112; 1990/4.36, 7.71, 10.99; 1991/1.9, 6.52, 9.87, 12.123; Ambua Lodge, Tari, New Guinea 1990/9.94 Ascot Park, near Bendigo, Vic. 1989/12.130 Barmah Forest Taragon Lodge 1985/9.95 Barnidgee Creek 1983/1.11 Barren Grounds Observatory Jamberoo, NSW 1987/8.78, 1989/5.45; 1990/3.14 Bellellen Rise, Grampians, Vic. 1986/1.11, 3.23, 4 35, 5 47, 6.59 Bellwood, NSW 1990/6.54, 9.95 Bemm River, Vic. 1986/4 35 Bendigo Area, Strathfieldsaye 1985/5.47 Bool Lagoon, SA 1989/7.68, 10.107 Bright, Forest Lodge 1983/1.91 Bright, Vic. 1991/10.106, 11.120 Broome, W.A. 1986/7.71; 1987/3.15, 4.36, 5.41, 6.52 Byron Bay Beach Resort, N.S.W. 1986/1.5, 3.23, 4.29, 5.47, 6.58, 7.71, 8.82, 9.95, 10.107, 11.120, 12.128; 1987/1.8, 3.14, 4.36, 5.41, 6.52 Byron Bay, Belongil Wood Resort 1985/9.95 Cape Liptrap 1983/1.11 Cape York Wilderness Lodge 1987/8.84, 9.94, 11.112; 1988/2.23 Capertee Valley, near Glen Davis, NSW 1990/3.22, 4.26, 5.45 Casino, N.S.W. -

Red Rock Lakes & Volcanic Craters

LAKES & VOLCANIC CRATERS RED ROCK Red Rock Volcanic Lookout is on the eastern edge of the Kanawinka Global Geopark. KGG is Australia’s first global geopark. Earth’s distant fiery past has strewn this landscape with worn cones, volcanic craters & numerous salt lakes. Warrion hill is home to the Gulidjan people. King Co-Co Coine was the last of their warriors. Stone walling still divides dairy & crop farms. Small settlements and the early “Squatters” rambling old mansions dot the rolling hills & plains. King Co-Co Coine of the Warrions 8 7 5 9 6 4 3 2 1 © Red Red District Progress Association 1. Turn north off the highway onto an ancient Map Artwork & lake bed raised by Warrion’s eruption 80,000 Brown Falcon by Barry Mousley. years ago forming Lake Colac and the salty Photography by Lake Corangamite. Helene Bell. 2. Red Rock Regional Theatre and Gallery Design by (RRRTAG). A converted old Cororooke church, Lyn Parrott. reflects the charm of its rural location. The state of art theatre and art gallery with a reputation for excellence is run by the community. The gallery opens weekends 11-4pm. Check www.redrockarts.com.au for other events. 3. Corunnun Homestead. From Lineen’s Rd view the red stables seen by the lake. It is said to be Victoria’s oldest continually lived in homestead. (Closed to the public). 4. Lake Corangamite Nature Reserve is Australia’s largest permanent salt lake and home to migratory birds, endangered Corangamite Water RED ROCK CIRCUIT Skink, lava flows and stone remnants of ancient Aboriginal fish traps and is part of the Ramsar Wetlands. -

Setting Resource Condition Targets

Corangamite Salinity Action Plan Background Report 9: Setting Resource Condition Targets Authored by: Peter Dahlhaus 1,2 , Chris Smitt 2, Jim Cox 2 & Cam Nicholson 3 1Dahlhaus Environmental Geology Pty Ltd, Buninyong 2CSIRO Land & Water, Adelaide 3Nicon Rural Services Pty Ltd, Queenscliff Published by the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, 2005 64 Dennis Street Colac Victoria 3250 Website: http://www.ccma.vic.gov.au First edition: December 2005 Preferred bibliographic citation: Dahlhaus P.G., Smitt C.M., Cox J.W. & Nicholson C. 2005. Corangamite Salinity Action Plan: Setting resource condition targets. Background Report 9, Corangamite Salinity Action Plan, Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, Colac Victoria. The National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: ISBN This document has been prepared for use by the Corangamite Catchment Management Authority by Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd and has been compiled by using the consultants’ expert knowledge, due care and professional expertise. The Corangamite Catchment Management Authority, Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd and other contributors do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for every purpose for which it may be used and therefore disclaim all liability for any error, loss, damage or other consequence whatsoever which may arise from the use of or reliance on the information contained in this publication. Corangamite Salinity Action Plan (2005 – 2008) Principal consultant: Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd Project team: Mike Stephens, Mike Stephens & Associates Pty Ltd Cam Nicholson, Nicon Rural Services Pty Ltd Peter Dahlhaus, Dahlhaus Environmental Geology Pty Ltd Graeme Anderson, Department of Primary Industries Roger Standen, Karlie Tucker & Clare Kelliher, Rendell McGuckian Pty Ltd Project management Tim Corlett, Corangamite CMA (2003) Felicia Choo, Corangamite CMA (2005) Cover Photo: Lake Cundare, a Ramsar-listed semi-permanent hypersaline wetland, near Cundare (P. -

Western District Lakes Ramsar Site Boundary Description

Western District Lakes Ramsar Site Boundary Description Technical Report Published by the Victorian Government Department of Environment and Primary Industries Melbourne, December 2013 © The State of Victoria Department of Environment and Primary Industries Melbourne 2013 This publication is copyright. No part may be reproduced by any process except in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright Act 1968 . Authorised by the Victorian Government, 8 Nicholson Street, East Melbourne. ISBN 978-174287-819-5 (PDF/online format) For more information contact the DEPI Customer Service Centre 136 186 Citation: DEPI (2013) Western District Lakes Ramsar Site Boundary Description Technical Report. Department of Environment and Primary Industries, East Melbourne, Victoria. Disclaimer This publication may be of assistance to you but the State of Victoria and its employees do not guarantee that the publication is without flaw of any kind or is wholly appropriate for your particular purposes and therefore disclaims all liability for any error, loss or other consequence which may arise from you relying on any information in this publication. Accessibility If you would like to receive this publication in an accessible format, such as large print or audio, please telephone 136 186, or email [email protected] Deaf, hearing impaired or speech impaired? Call us via the National Relay Service on 133 677 or visit www.relayservice.com.au This document is also available in PDF format on the internet at www.depi.vic.gov.au Cover photo: Lake Beeac, DEPI (2009). Contents Introduction 1 Methodology of RAMSR 100 GIS layer boundary realignment 2 Location 3 Written description of the Western District Lakes Ramsar Site 4 References 7 Appendix 1 8 Appendix 2 9 Appendix 3 10 Western District Lakes Ramsar Site Boundary Description Technical Report Introduction Ramsar wetlands are wetlands of international importance listed under the Convention of Wetlands (Rasmar, Iran 1971).