Ann Fitzpatrick

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

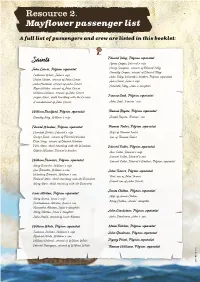

Resource 2 Mayflower Passenger List

Resource 2. Mayflower passenger list A full list of passengers and crew are listed in this booklet: Edward Tilley, Pilgrim separatist Saints Agnus Cooper, Edward’s wife John Carver, Pilgrim separatist Henry Sampson, servant of Edward Tilley Humility Cooper, servant of Edward Tilley Catherine White, John’s wife John Tilley, Edwards’s brother, Pilgrim separatist Desire Minter, servant of John Carver Joan Hurst, John’s wife John Howland, servant of John Carver Elizabeth Tilley, John’s daughter Roger Wilder, servant of John Carver William Latham, servant of John Carver Jasper More, child travelling with the Carvers Francis Cook, Pilgrim separatist A maidservant of John Carver John Cook, Francis’ son William Bradford, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Rogers, Pilgrim separatist Dorothy May, William’s wife Joseph Rogers, Thomas’ son Edward Winslow, Pilgrim separatist Thomas Tinker, Pilgrim separatist Elizabeth Barker, Edward’s wife Wife of Thomas Tinker George Soule, servant of Edward Winslow Son of Thomas Tinker Elias Story, servant of Edward Winslow Ellen More, child travelling with the Winslows Edward Fuller, Pilgrim separatist Gilbert Winslow, Edward’s brother Ann Fuller, Edward’s wife Samuel Fuller, Edward’s son William Brewster, Pilgrim separatist Samuel Fuller, Edward’s Brother, Pilgrim separatist Mary Brewster, William’s wife Love Brewster, William’s son John Turner, Pilgrim separatist Wrestling Brewster, William’s son First son of John Turner Richard More, child travelling with the Brewsters Second son of John Turner Mary More, child travelling -

William Bradford's Life and Influence Have Been Chronicled by Many. As the Co-Author of Mourt's Relation, the Author of of Plymo

William Bradford's life and influence have been chronicled by many. As the co-author of Mourt's Relation, the author of Of Plymouth Plantation, and the long-term governor of Plymouth Colony, his documented activities are vast in scope. The success of the Plymouth Colony is largely due to his remarkable ability to manage men and affairs. The information presented here will not attempt to recreate all of his activities. Instead, we will present: a portion of the biography of William Bradford written by Cotton Mather and originally published in 1702, a further reading list, selected texts which may not be usually found in other publications, and information about items related to William Bradford which may be found in Pilgrim Hall Museum. Cotton Mather's Life of William Bradford (originally published 1702) "Among those devout people was our William Bradford, who was born Anno 1588 in an obscure village called Ansterfield... he had a comfortable inheritance left him of his honest parents, who died while he was yet a child, and cast him on the education, first of his grand parents, and then of his uncles, who devoted him, like his ancestors, unto the affairs of husbandry. Soon a long sickness kept him, as he would afterwards thankfully say, from the vanities of youth, and made him the fitter for what he was afterwards to undergo. When he was about a dozen years old, the reading of the Scripture began to cause great impressions upon him; and those impressions were much assisted and improved, when he came to enjoy Mr. -

New England‟S Memorial

© 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. New England‟s Memorial: Or, A BRIEF RELATION OF THE MOST MEMORABLE AND REMARKABLE PASSAGES OF THE PROVIDENCE OF GOD, MANIFESTED TO THE PLANTERS OF NEW ENGLAND IN AMERICA: WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO THE FIRST COLONY THEREOF, CALLED NEW PLYMOUTH. AS ALSO A NOMINATION OF DIVERS OF THE MOST EMINENT INSTRUMENTS DECEASED, BOTH OF CHURCH AND COMMONWEALTH, IMPROVED IN THE FIRST BEGINNING AND AFTER PROGRESS OF SUNDRY OF THE RESPECTIVE JURISDICTIONS IN THOSE PARTS; IN REFERENCE UNTO SUNDRY EXEMPLARY PASSAGES OF THEIR LIVES, AND THE TIME OF THEIR DEATH. Published for the use and benefit of present and future generations, BY NATHANIEL MORTON, SECRETARY TO THE COURT, FOR THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH. Deut. xxxii. 10.—He found him in a desert land, in the waste howling wilderness he led him about; he instructed him, he kept him as the apple of his eye. Jer. ii. 2,3.—I remember thee, the kindness of thy youth, the love of thine espousals, when thou wentest after me in the wilderness, in the land that was not sown, etc. Deut. viii. 2,16.—And thou shalt remember all the way which the Lord thy God led thee this forty years in the wilderness, etc. CAMBRIDGE: PRINTED BY S.G. and M.J. FOR JOHN USHER OF BOSTON. 1669. © 2009, MayflowerHistory.com. All Rights Reserved. TO THE RIGHT WORSHIPFUL, THOMAS PRENCE, ESQ., GOVERNOR OF THE JURISDICTION OF NEW PLYMOUTH; WITH THE WORSHIPFUL, THE MAGISTRATES, HIS ASSISTANTS IN THE SAID GOVERNMENT: N.M. wisheth Peace and Prosperity in this life, and Eternal Happiness in that which is to come. -

Plimoth Sketches 1620-27.Qxp

A genealogical profile of Edward Tilley Birth: Edward Tilley was baptized at Henlow, Bedfordshire on May 27, 1588, son of Robert and Elizabeth (_____) Tilley. Death: He died in Plymouth Colony in the winter of 1620/1. Ship: Mayflower, 1620 Life in England: Edward Tilley most likely lived in Henlow until he emigrated to the Netherlands sometime after his mar- riage. Life in Holland: Edward Tilley worked as a weaver in Leiden. Life in New England: Edward Tilley,his wife,Agnes, and two relatives, Humilty Cooper and Henry Samson, came to Plymouth Colony in 1620. Edward was a member of several exploring parties, during one of which, he “had like to have sounded [swooned] with cold.”The Tilleys both died during the winter of 1620/1 although both children survived. Family: Edward Tilley and Agnes Cooper were married on June 20, 1614, in Henlow, Bedfordshire.There are no recorded children. For Further Information: Robert C. Anderson. The Great Migration Begins. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1995. Robert C. Anderson. The Pilgrim Migration. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2004. Robert L. Ward. “English Ancestry of Seven Mayflower Passengers: Tilley, Sampson, and Cooper.” The American Genealogist 52 (1976): 198–208. A collaboration between PLIMOTH PLANTATION and the NEW ENGLAND HISTORIC GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY® Supported by the Institute of Museum and Library Services www.PlymouthAncestors.org Researching your family’s history can be a fun, rewarding, and occa- sionally frustrating project. Start with what you know by collecting infor- mation on your immediate family. Then, trace back through parents, grandparents, and beyond.This is a great opportunity to speak to relatives, gather family stories, arrange and identify old family photographs, and document family possessions that have been passed down from earlier generations. -

Notes on Cole's Hill

NOTES ON COLE’S HILL by Edward R. Belcher Pilgrim Society Note, Series One, Number One, 1954 The designation of Cole‟s Hill as a registered National Historic Landmark by the National Park Service, Department of the Interior, was announced at the Annual Meeting of the Pilgrim Society on December 21, 1961. An official plaque will be placed on Cole‟s Hill. The formal application for this designation, made by the Society, reads in part: "... Fully conscious of the high responsibility to the Nation that goes with the ownership and care of a property classified as ... worthy of Registered National Historic Landmark status ... we agree to preserve... to the best of our ability, the historical integrity of this important part of our national cultural heritage ..." A tablet mounted on the granite post at the top of the steps on Cole‟s Hill bears this inscription: "In memory of James Cole Born London England 1600 Died Plymouth Mass 1692 First settler of Coles Hill 1633 A soldier in Pequot Indian War 1637 This tablet erected by his descendants1917" Cole‟s Hill, rising from the shore near the center of town and overlooking the Rock and the harbor, has occupied a prominent place in the affairs of the community. Here were buried the bodies of those who died during the first years of the settlement. From it could be watched the arrivals and departures of the many fishing and trading boats and the ships that came from time to time. In times of emergency, the Hill was fortified for the protection of the town. -

Docum Robert Tilley

Documentation for Robert Tilley (circa 1540 to Feb. 1612/3) father of John Tilley (Bef. Dec 19, 1571 to Jan to Mar, 1620/1) Robert Tilley was the father of eight children. John Tilley - son of Robert and Elizabeth Tilley. BAPTIZED: 19 December 1571, Henlow, Bedford, England, son of Robert and Elizabeth (---) Tilley. DIED: the first winter, between January and March, 1620/1, Plymouth MARRIED: Joan (Hurst) Rogers, 20 September 1596, Henlow, Bedford, England, widow of Thomas Rogers (no relation to Thomas Rogers of the Mayflower), and daughter of William and Rose (---) Hurst. *Note. Joan (Hurst) Rogers had a daughter Joan Rogers by her first marriage, bp. 26 May 1594, Henlow, Bedford, England. Joan married Edward Hawkins, probably a brother of her half-brother Robert's wife Mary Hawkins. CHILDREN: NAME BAPTISM DEATH MARRIAGE Rose 23 October 1597, Henlow, Bedford, England died young unmarried John 26 August 1599, Henlow, Bedford, England unknown unknown Rose 28 February 1601/2, Henlow, Bedford, England unknown unknown Robert 25 November 1604, Henlow, Bedford, England unknown Mary Hawkins in Bedford, England Elizabeth 30 August 1607, Henlow, Bedford, England 21 December 1687, Swansea, MA John Howland, cir 1625, Plymouth ANCESTRAL SUMMARY: John Tilley, his wife Joan (Hurst) Rogers, and daughter Elizabeth came on the Mayflower. John and Joan died the first winter, but Elizabeth lived, married John Howland, and had eleven children. John's brother Edward Tilley came with wife Ann Cooper on the Mayflower as well. John Tilley did not marry Prijntgen (Elizabeth) van der Velde in Holland. That was easily disproved in Mayflower Descendant 10:66-67, and by the subsequent identification of Joan (Hurst) Rogers. -

CHILDREN on the MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan

CHILDREN ON THE MAYFLOWER by Ruth Godfrey Donovan The "Mayflower" sailed from Plymouth, England, September 6, 1620, with 102 people aboard. Among the passengers standing at the rail, waving good-bye to relatives and friends, were at least thirty children. They ranged in age from Samuel Eaton, a babe in arms, to Mary Chilton and Constance Hopkins, fifteen years old. They were brought aboard for different reasons. Some of their parents or guardians were seeking religious freedom. Others were searching for a better life than they had in England or Holland. Some of the children were there as servants. Every one of the youngsters survived the strenuous voyage of three months. As the "Mayflower" made its way across the Atlantic, perhaps they frolicked and played on the decks during clear days. They must have clung to their mothers' skirts during the fierce gales the ship encountered on other days. Some of their names sound odd today. There were eight-year-old Humility Cooper, six-year-old Wrestling Brewster, and nine-year-old Love Brewster. Resolved White was five, while Damans Hopkins was only three. Other names sound more familiar. Among the eight-year- olds were John Cooke and Francis Billington. John Billington, Jr. was six years old as was Joseph Mullins. Richard More was seven years old and Samuel Fuller was four. Mary Allerton, who was destined to outlive all others aboard, was also four. She lived to the age of eighty-three. The Billington boys were the mischief-makers. Evidently weary of the everyday pastimes, Francis and John, Jr. -

Investigate Mayflower Biographies

Mayflower Biographies On 16th September 1620 the Mayflower set sail with 102 passengers plus crew (between 30 & 40). They spotted land in America on 9th November. William Bradford’s writings… William Bradford travelled on the Mayflower and he has left us some fantastic details about the passengers and settlers. The next few pages have some extracts from his writings. Bradford wrote: ‘The names of those which came over first, in the year 1620, and were by the blessing of God the first beginners and in a sort the foundation of all the Plantations and Colonies in New England; and their families.’ He ended the writings with the words: ‘From William Bradford, Of Plimoth Plantation, 1650’ Read ` If you want to read more see the separate document their Mayflower Biographies Also Click here to link to the stories… Mayflower 400 website Read their stories… Mr. John Carver, Katherine his wife, Desire Minter, and two manservants, John Howland, Roger Wilder. William Latham, a boy, and a maidservant and a child that was put to him called Jasper More. John was born by about 1585, making him perhaps 35 when the Mayflower sailed. He may have been one of the original members of the Scrooby Separatists. Katherine Leggatt was from a Nottinghamshire family and it’s thought that they married in Leiden before 1609. They buried a child there in 1617. In 1620, John was sent from Holland to London to negotiate the details of the migration. John was elected the governor of the Mayflower and, on arrival in America, he became the governor of the colony too. -

Our Church Life Page 1

OUR CHURCH LIFE PAGE 1 OUR CHURCH LIFE PLYMOUTH CONGREGATIONAL CHURCH DECEMBER 2020 GATHERED IN 1847 / EST. 1864 WWW.PLYMOUTHLANSING.ORG VOL. 106 / EDITION #12 WWW.FACEBOOK.COM/PLYMOUTHCHURCH.LANSING “The Lord hath more truth and light yet to break forth out of His holy Word.” – Minister John Robinson. But let’s back up a bit to when Robinson entered Leiden University in 1615 to study theology. By 1617 he and his followers were seeking a more secure and permanent location. In July 1620, while he remained with the majority who were not yet ready to travel, part of his congregation boarded on the Speedwell for England. Before their departure from Leiden, Robinson declared to them in a celebrated sermon, “For I am very confident the Lord hath more truth and light yet to break forth out of His holy Word.” The following September, 35 of them left Plymouth England aboard the The image above was shot from my Plimoth Mayflower for New England. As best intentions go, John Plantation mug. It details the 102 names of men, women, Robinson traded in his earthly pilgrim village for an and children aboard the Mayflower that later went on to eternal journal all before he could leave Holland. The settle the Plimoth Plantation. Yes, the word “Plimoth” is remaining members of his were absorbed by the Dutch not a misspelling but is actually the correct spelling of the Reformed Church in 1658. His influence persisted, little settlement dating to back when when the plantation however, not only in Plymouth Colony but also in his was settled. -

The Women Who Came in the Mayflower

The Women Who Came in the Mayflower Annie Russell Marble The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Women Who Came in the Mayflower by Annie Russell Marble Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: The Women Who Came in the Mayflower Author: Annie Russell Marble Release Date: January, 2005 [EBook #7252] [This file was first posted on March 31, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: US-ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK, THE WOMEN WHO CAME IN THE MAYFLOWER *** Dave Maddock, Charles Franks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. THE WOMEN WHO CAME IN THE MAYFLOWER BY 3 AUDIOBOOK COLLECTIONS 6 BOOK COLLECTIONS ANNIE RUSSELL MARBLE FOREWORD This little book is intended as a memorial to the women who came in _The Mayflower_, and their comrades who came later in _The Ann_ and _The Fortune_, who maintained the high standards of home life in early Plymouth Colony. -

Transatlantic Print Culture and the Rise of New England Literature, 1620-1630

TRANSATLANTIC PRINT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF NEW ENGLAND LITERATURE 1620-1630 by Sean Delaney to The Department of History In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the field of History Northeastern University Boston, MA April 2013 1 TRANSATLANTIC PRINT CULTURE AND THE RISE OF NEW ENGLAND LITERATURE 1620-1630 by Sean Delaney ABSTRACT OF DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate School of Northeastern University, April 2013 2 Transatlantic Print Culture And The Rise Of New England Literature 1620-1630 Despite the considerable attention devoted to the founding of puritan colonies in New England, scholars have routinely discounted several printed tracts that describe this episode of history as works of New England literature. This study examines the reasons for this historiographical oversight and, through a close reading of the texts, identifies six works written and printed between 1620 and 1630 as the beginnings of a new type of literature. The production of these tracts supported efforts to establish puritan settlements in New England. Their respective authors wrote, not to record a historical moment for posterity, but to cultivate a particular colonial reality among their contemporaries in England. By infusing puritan discourse into the language of colonization, these writers advanced a colonial agenda independent of commercial, political and religious imperatives in England. As a distinctive response to a complex set of historical circumstances on both sides of the Atlantic, these works collectively represent the rise of New England literature. 3 This dissertation is dedicated with love to my wife Tara and to my soon-to-be-born daughter Amelia Marie. -

ENGLISH HISTORICAL COMMENTARY the Mayflower Compact, November 21, 1620

ENGLISH HISTORICAL COMMENTARY The Mayflower Compact, November 21, 1620 IN THE NAME OF GOD, AMEN. We, whose names are underwritten, the Loyal Subjects of our dread Sovereign Lord King James, by the Grace of God, of Great Britain, France, and Ireland, King, Defender of the Faith, &c. Having undertaken for the Glory of God, and Advancement of the Christian Faith, and the Honour of our King and Country, a Voyage to plant the first Colony in the northern Parts of Virginia; Do by these Presents, solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, covenant and combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation, and Furtherance of the Ends aforesaid: And by Virtue hereof do enact, constitute, and frame, such just and equal Laws, Ordinances, Acts, Constitutions, and Officers, from time to time, as shall be thought most meet and convenient for the general Good of the Colony; unto which we promise all due Submission and Obedience. IN WITNESS whereof we have hereunto subscribed our names at Cape-Cod the eleventh of November, in the Reign of our Sovereign Lord King James, of England, France, and Ireland, the eighteenth, and of Scotland the fifty-fourth, Anno Domini; 1620. Mr. John Carver, Mr. William Mullins, Mr. William Bradford, Mr. William White, Mr Edward Winslow, Mr. Richard Warren, Mr. William Brewster. John Howland, Isaac Allerton, Mr. Steven Hopkins, Myles Standish, Digery Priest, John Alden, Thomas Williams, John Turner, Gilbert Winslow, Francis Eaton, Edmund Margesson, James Chilton, Peter Brown, John Craxton Richard Britteridge John Billington, George Soule, Moses Fletcher, Edward Tilly, John Goodman, John Tilly, Mr.