Eleven Myths About the Tuskegee Airmen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Get Ready for Luke Days 2020 by FCP Staff Luke Days, the Premier Air Show in the Phoenix Area, Is Returning March 21-22, 2020

Visions To serveFCP and support the men, women, families and mission of Luke Air Force Base Winter 2018 Get ready for Luke Days 2020 By FCP Staff Luke Days, the premier air show in the Phoenix area, is returning March 21-22, 2020. The U.S. Air Force Thunderbirds demonstration team will headline the free event throughout the two- day show. “Mark your calendars now because we can’t wait to host you in 2020,” Brig. Gen. Todd Canterbury, 56th Fighter Wing commander, said. “Luke Days is our chance to open up our gates and welcome the community on base to see their U.S. military up close. We love hosting you as a small thank you for the amazing support you give us year after year.” More than 250,000 attendees enjoyed the 2018 event, making it one of the most highly-attended events in Arizona. Stay tuned to the Luke Air Force Base social media accounts and website for updates on performers, ap- pearances and other details. Questions can be directed to the Luke AFB Public Affairs Office at 623-856-6011 or [email protected]. mil. Heritage jets fly high in a demonstration at Luke Days 2016. The airshow returns in 2020. (Photo special to FCP Visions) Fighter Country Partnership makes holidays bright for Airman By Bill Johnston ries. These airmen are young; mostly 18 to 20 years Program Director, Fighter Country Partnership old with most of them away from home for the first Tis the Season! That has been the topic of conver- time. This party is simply a positive distraction for sation in the Fighter Country Partnership office these these young men and women. -

Downloadable Content the Supermarine

AIRFRAME & MINIATURE No.12 The Supermarine Spitfire Part 1 (Merlin-powered) including the Seafire Downloadable Content v1.0 August 2018 II Airframe & Miniature No.12 Spitfire – Foreign Service Foreign Service Depot, where it was scrapped around 1968. One other Spitfire went to Argentina, that being PR Mk XI PL972, which was sold back to Vickers Argentina in March 1947, fitted with three F.24 cameras with The only official interest in the Spitfire from the 8in focal length lens, a 170Imp. Gal ventral tank Argentine Air Force (Fuerca Aerea Argentina) was and two wing tanks. In this form it was bought by an attempt to buy two-seat T Mk 9s in the 1950s, James and Jack Storey Aerial Photography Com- PR Mk XI, LV-NMZ with but in the end they went ahead and bought Fiat pany and taken by James Storey (an ex-RAF Flt Lt) a 170Imp. Gal. slipper G.55Bs instead. F Mk IXc BS116 was allocated to on the 15th April 1947. After being issued with tank installed, it also had the Fuerca Aerea Argentina, but this allocation was the CofA it was flown to Argentina via London, additional fuel in the cancelled and the airframe scrapped by the RAF Gibraltar, Dakar, Brazil, Rio de Janeiro, Montevi- wings and fuselage before it was ever sent. deo and finally Buenos Aires, arriving at Morón airport on the 7th May 1947 (the exhausts had burnt out en route and were replaced with those taken from JF275). Storey hoped to gain an aerial mapping contract from the Argentine Government but on arrival was told that his ‘contract’ was not recognised and that his services were not required. -

Department of the Air Force Presentation to the Committee on Armed Services Subcommittee on Military Personnel United States

DEPARTMENT OF THE AIR FORCE PRESENTATION TO THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES SUBCOMMITTEE ON MILITARY PERSONNEL UNITED STATES SENATE SUBJECT: AIR FORCE RESERVE PROGRAMS STATEMENT OF: Lieutenant General James E. Sherrard III Chief of Air Force Reserve MARCH 31, 2004 NOT FOR PUBLICATION UNTIL RELEASED BY THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE 1 Air Force Reserve 2004 Posture Statement Mr Chairman, and distinguished members of the Committee, I would like to offer my sincere thanks for this opportunity, my last, to testify before you. As of 30 Sep 03, United States Air Force Reserve (USAFR) has a total of 8,135 people mobilized under Partial Mobilization Authority. These individuals are continuing to perform missions involving; Security, Intelligence, Flight Operations for Combat Air Patrols (CAPs), Communications, Air Refueling Operations, Strategic and Tactical Airlift Operations, Aero Medical, Maintenance, Civil Engineering and Logistics. The Partial Mobilization for the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT) is the longest sustained, large-scale mobilization in the history of the Air Force. AFR mobilizations peaked at 15,332 on April 16, 2003 during OIF with a cumulative 28,239 mobilizations sourced in every contingency supporting GWOT since September 11, 2001. Early GWOT operations driven by rapid onset events and continued duration posed new mobilization and re- mobilization challenges, which impacted OIF even though only a portion of the Reserve capability was tapped. In direct support of Operation ENDURING FREEDOM (OEF), Operation IRAQI FREEDOM (OIF), and the Global War on Terrorism (GWOT), Air Force Reservists have flown a multitude of combat missions into Afghanistan and Iraq. The 93rd Bomb Squadron is an example of one of the many units to successfully integrate with active duty forces during combat missions in OEF and OIF. -

United States Air Force Lieutenant General Richard W. Scobee

UNITED STATES AIR FORCE LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARD W. SCOBEE Lt. Gen. Richard W. Scobee is the Chief of Air Force Reserve, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Arlington, Va., and Commander, Air Force Reserve Command, Robins Air Force Base, Georgia. As Chief of Air Force Reserve, he serves as principal adviser on reserve matters to the Secretary of the Air Force and the Air Force Chief of Staff. As Commander of Air Force Reserve Command, he has full responsibility for the supervision of all Air Force Reserve units around the world. Lt. Gen. Scobee was commissioned in 1986 as a graduate of the Air Force Academy. He earned his pilot wings as a distinguished graduate of Euro- NATO Joint Jet Pilot training in 1987. He has served as an F-16 Fighting Falcon Pilot, Instructor Pilot and Flight Examiner both domestically and overseas in Germany, South Korea and Egypt. Lt. Gen. Scobee has commanded a fighter squadron, operations group, two fighter wings and a numbered Air Force. Additionally, he deployed as Commander of the 506th Air Expeditionary Group, Kirkuk Regional Air Base, Iraq, in 2008. Prior to his current assignment, Lt. Gen. Scobee, was the Deputy Commander, Air Force Reserve Command, where he was responsible for the daily operations of the command, consisting of approximately 70,000 Reserve Airmen and more than 300 aircraft among three numbered air forces, 34 flying wings, 10 flying groups, a space wing, a cyber wing and an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance wing. He is a command pilot with more than 3,800 flying hours in the F-16, including 248 combat hours. -

Spring 2017 Issue-All

SPRING 2017 - Volume 64, Number 1 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

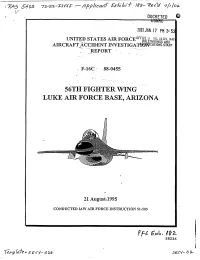

Report of F-16 Accident Which Occurred on 08/21/95

W15 5ý 63 -7 - I-Ts r17 - 4pplica rt Sei 4'1.- hle2- wee'd v DOCKETED 0 2003 JAN 17 PM 3: 53 UNITED STATES AIR FORCEA OFFICE o• 1h- SEUL AR'A AIRCRAFT ACCIDENT INVESTIGA-T¶ ICATIONS STAFF REPORT F-16C , 88-0455 56TH FIGHTER WING LUKE AIR FORCE BASE, ARIZONA (I N i 21 August.1995 CONDUCTED IAW AIR FORCE INSTRUCTION 51-503 eF-s 6dI4. lk? 58236 pla-e = -TsECV- 4o a- EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Aircraft Investigation Report F-16CG (SN 88-0455) Luke AFB, AZ 21 August 1995 Fighter During the afternoon of 21 August 1995, an F-16 assigned to the 308th Fighter Squadron, 56th flight Wing, Luke Air Force Base, Arizona, was conducting a three ship Air Combat Maneuvering (ACM) from lead upgrade (FLUG) mission. At 1618 PST, at a position approximately 60 nautical miles northwest the Phoenix, the engine failed. The pilot ejected safely and the aircraft was destroyed upon impacting injury. ground in an unpopulated area on government land. There was no property damage or personal other data, the After extensive witness interviews, review of maintenance documents, engine records, and pressure turbine. This Accident Investigating Officer found that the engine experienced a failure of the low caused the accident. 58237 AFI 51-503 ACCIDENT INVESTIGATION REPORT Commander AUTHORITY. In a letter dated 5 September 1995, Major General Nicholas B. Kehoe, an 19th Air Force, appointed Colonel James B. Smith, 325 OG/CC, Tyndall AFB, Florida, to conduct an investigation pursuant to Air Force Instruction (AFI) 51-503 into the circumstances surrounding aircraft accident involving F-16CG, tail number 88-0455, assigned to the 308th Fighter Squadron, 56th Fighter Wing, Luke Air Force Base, Arizona. -

Welcome to Kunsan Air Base

Welcome to Kunsan Air Base "Home of the Wolf Pack" Dear Guest, Welcome to Wolf Pack Lodge, the newest AF Lodging facility in the ROK. Kunsan Air Base is home to the 8th Fighter Wing, also known as the "Wolf Pack," a nickname given during the command of Colonel Robin Olds in 1966. Our mission is; "Defend the Base, Accept Follow on Forces, and Take the Fight North," the warriors here do an amazing job ensuring mission success. Kunsan AB plays host to many personnel, in all branches of the service, in support of our numerous peninsula wide exercises each year. We are proud to serve all the war fighters who participate in these exercises and ensure our "Fight Tonight" capability. To ensure you have a great stay with us, I would ask that you report any problem with your room to our front desk staff immediately, so we can try to resolve the issue, and you can focus on your mission here. If any aspect of your stay is less than you would hope for, please call me at 782-1844 ext. 160, or just dial 160 from your room phone. You may also e-mail me at [email protected] , I will answer you as quickly as possible. We are required to enter each room at least every 72 hours, this is not meant to inconvenience you, but to make sure you are okay, and see if there is anything you need. If you will be working shift work while here and would like to set up a time that is best for you to receive housekeeping service, please dial 157 from your room phone, and the Housekeeping Manager would be happy to schedule your cleaning between 0800 and 1600. -

Air Force Reserve Posture Statement March 3, 2020

United States Air Force Testimony Before the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense Guard and Reserve Hearing Statement of Lieutenant General Richard W. Scobee Chief of Air Force Reserve March 03, 2020 Not for publication until released by the House Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense UNITED STATES AIR FORCE LIEUTENANT GENERAL RICHARD W. SCOBEE Lt. Gen. Richard W. Scobee is the Chief of Air Force Reserve, Headquarters U.S. Air Force, Arlington, Va., and Commander, Air Force Reserve Command, Robins Air Force Base, Georgia. As Chief of Air Force Reserve, he serves as principal adviser on reserve matters to the Secretary of the Air Force and the Air Force Chief of Staff. As Commander of Air Force Reserve Command, he has full responsibility for the supervision of all Air Force Reserve units around the world. Lt. Gen. Scobee was commissioned in 1986 as a graduate of the Air Force Academy. He earned his pilot wings as a distinguished graduate of Euro- NATO Joint Jet Pilot training in 1987. He has served as an F-16 Fighting Falcon Pilot, Instructor Pilot and Flight Examiner both domestically and overseas in Germany, South Korea and Egypt. Lt. Gen. Scobee has commanded a fighter squadron, operations group, two fighter wings and a numbered Air Force. Additionally, he deployed as Commander of the 506th Air Expeditionary Group, Kirkuk Regional Air Base, Iraq, in 2008. Prior to his current assignment, Lt. Gen. Scobee, was the Deputy Commander, Air Force Reserve Command, where he was responsible for the daily operations of the command, consisting of approximately 70,000 Reserve Airmen and more than 300 aircraft among three numbered air forces, 34 flying wings, 10 flying groups, a space wing, a cyber wing and an intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance wing. -

308Th FIGHTER SQUADRON

308th FIGHTER SQUADRON MISSION LINEAGE 308th Pursuit Squadron (Interceptor) constituted, 21 Jan 1942 Activated, 30 Jan 1942 Redesignated 308th Fighter Squadron, 25 May 1942 Redesignated 308th Fighter Squadron, Single Engine, 20 Aug 1943 Inactivated, 7 Nov 1945 Activated, 20 Aug 1946 Redesignated 308th Fighter Squadron, Jet, 15 Jun 1948 Redesignated 308th Fighter Bomber Squadron, 20 Jan 1950 Redesignated 308th Fighter Escort Squadron, 16 Jul 1950 Redesignated 308th Strategic Fighter Squadron, 20 Jan 1953 Redesignated 308th Fighter-Bomber Squadron, 1 Apr 1957 Redesignated 308th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 1 Jul 1958 Redesignated 308th Tactical Fighter Training Squadron, 9 Oct 1980 Redesignated 308th Tactical Fighter Squadron, 1 Oct 1986 Redesignated 308th Fighter Squadron, 1 Nov 1991 STATIONS Baer Field, IN, 30 Jan 1942 New Orleans AB, LA, 6 Feb–19 May 1942 Atcham, England, 10 Jun 1942 Kenley, England, 1 Aug 1942 Westhampnett, England, 25 Aug–23 Oct 1942 Tafaraoui, Algeria, 8 Nov 1942 (operated from Casablanca, French Morocco, 10–31 Jan 1943) Thelepte, Tunisia, 6 Feb 1943 Tebessa, Algeria, 17 Feb 1943 Canrobert, Algeria, 21 Feb 1943 Kalaa Djerda, Tunisia, 25 Feb 1943 Thelepte, Tunisia, 11 Mar 1943 Djilma, Tunisia, 7 Apr 1943 Le Sers, Tunisia, 12 Apr 1943 Korba, Tunisia, 20 May 1943 Gozo, c. 30 Jun 1943 Ponte Olivo, Sicily, 14 Jul 1943 Agrigento, Sicily, 19 Jul 1943 Termini, Sicily, 2 Aug 1943 Milazzo, Sicily, 2 Sep 1943 Montecorvino, Italy, 20 Sep 1943 Pomigliano, Italy, 14 Oct 1943 Castel Volturno, Italy, 14 Jan 1944 San Severo, Italy, -

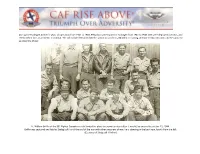

Learn More About the 32 Captured Tuskegee Airmen Pows

During the Tuskegee Airmen’s years of operation from 1941 to 1949, 992 pilots were trained in Tuskegee from 1941 to 1946. 450 were deployed overseas, and 150 lost their lives in accidents or combat. The toll included 66 pilots killed in action or accidents, 84 killed in training and non-combat missions and 32 captured as prisoners of war. Lt. William Griffin of the 99th Fighter Squadron crash-landed his plane in enemy territory after it was hit by enemy fire on Jan. 15, 1944. Griffin was captured and held at Stalag Luft I until the end of the war with other prisoners of war; he is standing in the back row, fourth from the left. (Courtesy of Stalg Luft I Online) PRISONER OF WAR MEDAL Established: 1986 Significance: Recognizes anyone who was a prisoner of war after April 5, 1917. Design: On the obverse, an American eagle with wings folded is enclosed by a ring. On the reverse, "Awarded to" is inscribed with space for the recipient's name, followed by "For honorable service while a prisoner of war" on three lines. The ribbon has a wide center stripe of black, flanked by a narrow white stripe, a thin blue stripe, a thin white stripe and a thin red stripe at the edge. Authorized device: Multiple awards are marked with a service star. MACR- Missing Air Crew Reports In May 1943, the Army Air Forces recommended the adoption of a special form, the Missing Air Crew Report (MACR), devised to record relevant facts of the last known circumstances regarding missing air crews, providing a means of integrating current data with information obtained later from other sources in an effort to conclusively determine the fate of the missing personnel. -

2010-Fall.Pdf

FALL 2010 - Volume 57, Number 3 WWW.AFHISTORICALFOUNDATION.ORG The Air Force Historical Foundation Founded on May 27, 1953 by Gen Carl A. “Tooey” Spaatz MEMBERSHIP BENEFITS and other air power pioneers, the Air Force Historical All members receive our exciting and informative Foundation (AFHF) is a nonprofi t tax exempt organization. Air Power History Journal, either electronically or It is dedicated to the preservation, perpetuation and on paper, covering: all aspects of aerospace history appropriate publication of the history and traditions of American aviation, with emphasis on the U.S. Air Force, its • Chronicles the great campaigns and predecessor organizations, and the men and women whose the great leaders lives and dreams were devoted to fl ight. The Foundation • Eyewitness accounts and historical articles serves all components of the United States Air Force— Active, Reserve and Air National Guard. • In depth resources to museums and activities, to keep members connected to the latest and AFHF strives to make available to the public and greatest events. today’s government planners and decision makers information that is relevant and informative about Preserve the legacy, stay connected: all aspects of air and space power. By doing so, the • Membership helps preserve the legacy of current Foundation hopes to assure the nation profi ts from past and future US air force personnel. experiences as it helps keep the U.S. Air Force the most modern and effective military force in the world. • Provides reliable and accurate accounts of historical events. The Foundation’s four primary activities include a quarterly journal Air Power History, a book program, a • Establish connections between generations. -

Tuskegee Airmen at Oscoda Army Air Field David K

WINTER 2016 - Volume 63, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future Our Sponsors Our Donors A Special Thanks to Members for their Sup- Dr Richard P. Hallion port of our Recent Events Maj Gen George B. Harrison, USAF (Ret) Capt Robert Huddleston and Pepita Huddleston Mr. John A. Krebs, Jr. A 1960 Grad Maj Gen Dale Meyerrose, USAF (Ret) Col Richard M. Atchison, USAF (Ret) Lt Gen Christopher Miller The Aviation Museum of Kentucky Mrs Marilyn S. Moll Brig Gen James L. Colwell, USAFR (Ret) Col Bobby B. Moorhatch, USAF (Ret) Natalie W. Crawford Gen Lloyd Fig Newton Lt Col Michael F. Devine, USAF (Ret) Maj Gen Earl G Peck, USAF (Ret) Maj Gen Charles J. Dunlap, Jr., USAF (Ret) Col Frederic H Smith, III, USAF (Ret) SMSgt Robert A. Everhart, Jr., USAF (Ret) Don Snyder Lt Col Raymond Fredette, USAF (Ret) Col Darrel Whitcomb, USAFR (Ret) Winter 2016 -Volume 63, Number 4 WWW.AFHISTORY.ORG know the past .....Shape the Future Features Boyd Revisited: A Great Mind with a Touch of Madness John Andreas Olsen 7 Origins of Inertial Navigation Thomas Wildenberg 17 The World War II Training Experiences of the Tuskegee Airmen at Oscoda Army Air Field David K. Vaughan 25 Ralph S. Parr, Jr., USAF Fighter Pilot Extraordinaire Daniel L. Haulman 41 All Through the Night, Rockwell Field 1923, Where Air-to-Air Refueling Began Robert Bruce Arnold 45 Book Reviews Thor Ballistic Missile: The United States and the United Kingdom in Partnership By John Boyes Review by Rick W. Sturdevant 50 An Illustrated History of the 1st Aero Squadron at Camp Furlong: Columbus, New Mexico 1916-1917 By John L.