A Genome-Wide Association and Admixture Mapping Study of Bronchodilator Drug Response in African Americans with Asthma

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes

Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes by Sayed Mohsen Hosseini A thesis submitted in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto © Copyright by S. Mohsen Hosseini 2014 Genetic Analysis of Retinopathy in Type 1 Diabetes Sayed Mohsen Hosseini Doctor of Philosophy Institute of Medical Science University of Toronto 2014 Abstract Diabetic retinopathy (DR) is a leading cause of blindness worldwide. Several lines of evidence suggest a genetic contribution to the risk of DR; however, no genetic variant has shown convincing association with DR in genome-wide association studies (GWAS). To identify common polymorphisms associated with DR, meta-GWAS were performed in three type 1 diabetes cohorts of White subjects: Diabetes Complications and Control Trial (DCCT, n=1304), Wisconsin Epidemiologic Study of Diabetic Retinopathy (WESDR, n=603) and Renin-Angiotensin System Study (RASS, n=239). Severe (SDR) and mild (MDR) retinopathy outcomes were defined based on repeated fundus photographs in each study graded for retinopathy severity on the Early Treatment Diabetic Retinopathy Study (ETDRS) scale. Multivariable models accounted for glycemia (measured by A1C), diabetes duration and other relevant covariates in the association analyses of additive genotypes with SDR and MDR. Fixed-effects meta- analysis was used to combine the results of GWAS performed separately in WESDR, ii RASS and subgroups of DCCT, defined by cohort and treatment group. Top association signals were prioritized for replication, based on previous supporting knowledge from the literature, followed by replication in three independent white T1D studies: Genesis-GeneDiab (n=502), Steno (n=936) and FinnDiane (n=2194). -

Centre for Arab Genomic Studies a Division of Sheikh Hamdan Award for Medical Sciences

Centre for Arab Genomic Studies A Division of Sheikh Hamdan Award for Medical Sciences The atalogue for ransmission enetics in rabs C T G A CTGA Database Ankyrin Repeat- And SOCS Box-Containing Protein 3 Alternative Names Monies et al. (2017) investigated the findings of ASB3 1000 diagnostic panels and exomes carried out at a next generation sequencing lab in Saudi Arabia. Record Category One patient, a 10-year-old female, presented with Gene locus ataxia, dystonia and hypertonia. An MRI revealed bilateral basal ganglia disease. The patient was WHO-ICD from a consanguineous family and had a brother N/A to gene loci with epilepsy. Using whole exome sequencing, a homozygous mutation (c.386-3T>C) was identified Incidence per 100,000 Live Births in exon 5 of the patient’s ASB3 gene. This gene N/A to gene loci mutation was considered a candidate for pathogenicity as it was a novel variant located OMIM Number within the autozygome that was predicted to be 605760 deleterious, and the ASB3 gene is expressed in the forebrain. The authors noted that further studies are Mode of Inheritance required to independently confirm this association. N/A to gene loci References Gene Map Locus Monies D, Abouelhoda M, AlSayed M, Alhassnan 2p16.2 Z, Alotaibi M, Kayyali H, Al-Owain M, Shah A, Rahbeeni Z, Al-Muhaizea MA, Alzaidan HI, Description Cupler E, Bohlega S, Faqeih E, Faden M, Alyounes The ASB3 gene encodes a protein belonging to the B, Jaroudi D, Goljan E, Elbardisy H, Akilan A, ankyrin repeat and SOCS box-containing (ASB) Albar R, Aldhalaan H, Gulab S, Chedrawi A, Al family. -

DNA Methylation Alterations in Blood Cells of Toddlers with Down Syndrome

G C A T T A C G G C A T genes Article DNA Methylation Alterations in Blood Cells of Toddlers with Down Syndrome Oxana Yu. Naumova 1,2,* , Rebecca Lipschutz 2, Sergey Yu. Rychkov 1, Olga V. Zhukova 1 and Elena L. Grigorenko 2,3,4,* 1 Vavilov Institute of General Genetics RAS, 119991 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] (S.Y.R.); [email protected] (O.V.Z.) 2 Department of Psychology, University of Houston, Houston, TX 77204, USA; [email protected] 3 Department of Psychology, Saint-Petersburg State University, 199034 Saint Petersburg, Russia 4 Department of Molecular and Human Genetics, Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX 77030, USA * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected] (O.Y.N.); [email protected] (E.L.G.) Abstract: Recent research has provided evidence on genome-wide alterations in DNA methylation patterns due to trisomy 21, which have been detected in various tissues of individuals with Down syndrome (DS) across different developmental stages. Here, we report new data on the systematic genome-wide DNA methylation perturbations in blood cells of individuals with DS from a previously understudied age group—young children. We show that the study findings are highly consistent with those from the prior literature. In addition, utilizing relevant published data from two other developmental stages, neonatal and adult, we track a quasi-longitudinal trend in the DS-associated DNA methylation patterns as a systematic epigenomic destabilization with age. Citation: Naumova, O.Y.; Lipschutz, R.; Rychkov, S.Y.; Keywords: Down syndrome; infants and toddlers; trisomy 21; DNA methylation; Illumina 450K Zhukova, O.V.; Grigorenko, E.L. -

Using Gene Expression Databases for Classical Trait QTL Candidate Gene Discovery in the BXD Recombinant Inbred Genetic Reference Population: Mouse Forebrain Weight

BMC Genomics BioMed Central Research article Open Access Using gene expression databases for classical trait QTL candidate gene discovery in the BXD recombinant inbred genetic reference population: Mouse forebrain weight Lu Lu*1,2, Lai Wei4,5, Jeremy L Peirce2, Xusheng Wang2, Jianhua Zhou6, Ramin Homayouni5, Robert W Williams2 and David C Airey*3 Address: 1Jiangsu Key Laboratory of Neuroregeneration, Nantong University, PR China, 2Department of Anatomy and Neurobiology, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, TN, 38103, USA, 3Department of Pharmacology, Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, Nashville, TN, 37232, USA, 4Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, TN, 38103, USA, 5Department of Neurology, University of Tennessee Health Sciences Center, Memphis, TN, 38103, USA and 6Department of Medicine, University of Massachusetts Medical School, Worcester, MA, 01605, USA Email: Lu Lu* - [email protected]; Lai Wei - [email protected]; Jeremy L Peirce - [email protected]; Xusheng Wang - [email protected]; Jianhua Zhou - [email protected]; Ramin Homayouni - [email protected]; Robert W Williams - [email protected]; David C Airey* - [email protected] * Corresponding authors Published: 25 September 2008 Received: 30 April 2008 Accepted: 25 September 2008 BMC Genomics 2008, 9:444 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-9-444 This article is available from: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/9/444 © 2008 Lu et al; licensee BioMed Central Ltd. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

The Genome-Wide Impact of Trisomy 21 on DNA Methylation and Its Implications for Hematopoiesis

UCSF UC San Francisco Previously Published Works Title The genome-wide impact of trisomy 21 on DNA methylation and its implications for hematopoiesis. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/2dx458vx Journal Nature communications, 12(1) ISSN 2041-1723 Authors Muskens, Ivo S Li, Shaobo Jackson, Thomas et al. Publication Date 2021-02-05 DOI 10.1038/s41467-021-21064-z Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-021-21064-z OPEN The genome-wide impact of trisomy 21 on DNA methylation and its implications for hematopoiesis Ivo S. Muskens1,2, Shaobo Li 1,2,13, Thomas Jackson3,13, Natalina Elliot3,13, Helen M. Hansen4, Swe Swe Myint1,2, Priyatama Pandey1,2, Jeremy M. Schraw5,6, Ritu Roy7, Joaquin Anguiano4, Katerina Goudevenou3, Kimberly D. Siegmund 8, Philip J. Lupo5,6, Marella F. T. R. de Bruijn 9, Kyle M. Walsh 10,11, Paresh Vyas 9, Xiaomei Ma12, Anindita Roy 3, Irene Roberts3, Joseph L. Wiemels1,2 & ✉ Adam J. de Smith 1,2 1234567890():,; Down syndrome is associated with genome-wide perturbation of gene expression, which may be mediated by epigenetic changes. We perform an epigenome-wide association study on neonatal bloodspots comparing 196 newborns with Down syndrome and 439 newborns without Down syndrome, adjusting for cell-type heterogeneity, which identifies 652 epigenome-wide significant CpGs (P < 7.67 × 10−8) and 1,052 differentially methylated regions. Differential methylation at promoter/enhancer regions correlates with gene expression changes in Down syndrome versus non-Down syndrome fetal liver hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (P < 0.0001). -

Network-Based Method for Drug Target Discovery at the Isoform Level

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Network-based method for drug target discovery at the isoform level Received: 20 November 2018 Jun Ma1,2, Jenny Wang2, Laleh Soltan Ghoraie2, Xin Men3, Linna Liu4 & Penggao Dai 1 Accepted: 6 September 2019 Identifcation of primary targets associated with phenotypes can facilitate exploration of the underlying Published: xx xx xxxx molecular mechanisms of compounds and optimization of the structures of promising drugs. However, the literature reports limited efort to identify the target major isoform of a single known target gene. The majority of genes generate multiple transcripts that are translated into proteins that may carry out distinct and even opposing biological functions through alternative splicing. In addition, isoform expression is dynamic and varies depending on the developmental stage and cell type. To identify target major isoforms, we integrated a breast cancer type-specifc isoform coexpression network with gene perturbation signatures in the MCF7 cell line in the Connectivity Map database using the ‘shortest path’ drug target prioritization method. We used a leukemia cancer network and diferential expression data for drugs in the HL-60 cell line to test the robustness of the detection algorithm for target major isoforms. We further analyzed the properties of target major isoforms for each multi-isoform gene using pharmacogenomic datasets, proteomic data and the principal isoforms defned by the APPRIS and STRING datasets. Then, we tested our predictions for the most promising target major protein isoforms of DNMT1, MGEA5 and P4HB4 based on expression data and topological features in the coexpression network. Interestingly, these isoforms are not annotated as principal isoforms in APPRIS. -

Content Based Search in Gene Expression Databases and a Meta-Analysis of Host Responses to Infection

Content Based Search in Gene Expression Databases and a Meta-analysis of Host Responses to Infection A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Drexel University by Francis X. Bell in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy November 2015 c Copyright 2015 Francis X. Bell. All Rights Reserved. ii Acknowledgments I would like to acknowledge and thank my advisor, Dr. Ahmet Sacan. Without his advice, support, and patience I would not have been able to accomplish all that I have. I would also like to thank my committee members and the Biomed Faculty that have guided me. I would like to give a special thanks for the members of the bioinformatics lab, in particular the members of the Sacan lab: Rehman Qureshi, Daisy Heng Yang, April Chunyu Zhao, and Yiqian Zhou. Thank you for creating a pleasant and friendly environment in the lab. I give the members of my family my sincerest gratitude for all that they have done for me. I cannot begin to repay my parents for their sacrifices. I am eternally grateful for everything they have done. The support of my sisters and their encouragement gave me the strength to persevere to the end. iii Table of Contents LIST OF TABLES.......................................................................... vii LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................ xiv ABSTRACT ................................................................................ xvii 1. A BRIEF INTRODUCTION TO GENE EXPRESSION............................. 1 1.1 Central Dogma of Molecular Biology........................................... 1 1.1.1 Basic Transfers .......................................................... 1 1.1.2 Uncommon Transfers ................................................... 3 1.2 Gene Expression ................................................................. 4 1.2.1 Estimating Gene Expression ............................................ 4 1.2.2 DNA Microarrays ...................................................... -

Stage-Differentiated Modelling of DNA Methylation Landscapes Uncovers Salient Biomarkers and Prognostic Signatures in Colorectal Cancer Progression

medRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.09.28.20203539; this version posted December 23, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted medRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under a CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 International license . Stage-differentiated modelling of DNA methylation landscapes uncovers salient biomarkers and prognostic signatures in colorectal cancer progression Sangeetha Muthamilselvan1e, Abirami Raghavendran1e, Ashok Palaniappan1* 1Department of Bioinformatics, School of Chemical and BioTechnology, SASTRA Deemed University, Thanjavur 613401. India eThese authors contributed equally *Corresponding author ([email protected]) ABSTRACT Background: Aberrant methylation of DNA acts epigenetically to skew the gene transcription rate up or down. In this study, we have developed a comprehensive computational framework for the stage-differentiated modelling of DNA methylation landscapes in colorectal cancer. Methods: The methylation β - matrix was derived from the public-domain TCGA data, converted into M-value matrix, annotated with sample stages, and analysed for stage-salient genes using multiple approaches involving stage-differentiated linear modelling of methylation patterns and/or expression patterns. Differentially methylated genes (DMGs) were identified using a contrast against control samples (adjusted p-value <0.001 and |log fold-change of M-value| >2). These results were filtered using a series of all possible pairwise stage contrasts (p-value <0.05) to obtain stage-salient DMGs. These were then subjected to a consensus analysis, followed by Kaplan–Meier survival analysis to explore the relationship between methylation and prognosis for the consensus stage-salient biomarkers. -

Supplementary Table 1-All DNM.Xlsx

Pathogenicity Patient ID Origin Semen analysis Gene Chromosome coordinates (GRCh37) Refseq ID HGVS Expressed in testis prediction* Proband_005 Netherlands Azoospermia CDK5RAP2 chr9:123215805 NM_018249:c.2722C>T p.Arg908Trp SP Yes, not enhanced ATP1A1 chr1:116930014 NM_000701:c.291del p.Phe97LeufsTer44 N/A Yes, not enhanced TLN2 chr15:63029134 NM_015059:c.3416G>A p.Gly1139Glu MP Yes, not enhanced Proband_006 Netherlands Azoospermia HUWE1 chrX:53589090 NM_031407:c.7314_7319del p.Glu2439_Glu2440del N/A Yes, not enhanced ABCC10 chr6:43417749 NM_001198934:c.4399C>T p.Arg1467Cys - Yes, not enhanced Proband_008 Netherlands Azoospermia CP chr3:148927135 NM_000096c.644G>A p.Arg215Gln - Not expressed FUS chr16:31196402 NM_004960:c.678_686del p.Gly229_Gly231del N/A Yes, not enhanced Proband_010 Netherlands Azoospermia LTBP1 chr2:33246090 NM_206943:c.680C>G p.Ser227Trp P Yes, not enhanced Proband_012 Netherlands Extreme oligozoospermia RP1L1 chr8:10480174 NM_178857:c.538G>A p.Ala180Thr SP Yes, not enhanced Proband_013 Netherlands Azoospermia ERG chr21:39755563 NM_182918:c.1202C>T p.Pro401Leu MP Yes, not enhanced Proband_017 Netherlands Azoospermia CDC5L chr6:44413480 NM_001253:c.2180G>A p.Arg727His SMP Yes, not enhanced Proband_019 Netherlands Azoospermia ABLIM1 chr10:116205100 NM_002313:c.1798C>T p.Arg600Trp SMP Yes, not enhanced CCDC126 chr7:23682709 NM_001253:c.2180G>A p.Thr133Met - Yes, enhanced expression in testis Proband_020 Netherlands Azoospermia RASEF chr9:85607885 NM_152573:c.1976G>A p.Arg659His SMP Yes, not enhanced Proband_022 Netherlands -

Contribution of Type W Human Endogenous

Grandi et al. Retrovirology (2016) 13:67 DOI 10.1186/s12977-016-0301-x Retrovirology RESEARCH Open Access Contribution of type W human endogenous retroviruses to the human genome: characterization of HERV‑W proviral insertions and processed pseudogenes Nicole Grandi1 , Marta Cadeddu1 , Jonas Blomberg2 and Enzo Tramontano1,3* Abstract Background: Human endogenous retroviruses (HERVs) are ancient sequences integrated in the germ line cells and vertically transmitted through the offspring constituting about 8 % of our genome. In time, HERVs accumulated muta- tions that compromised their coding capacity. A prominent exception is HERV-W locus 7q21.2, producing a functional Env protein (Syncytin-1) coopted for placental syncytiotrophoblast formation. While expression of HERV-W sequences has been investigated for their correlation to disease, an exhaustive description of the group composition and char- acteristics is still not available and current HERV-W group information derive from studies published a few years ago that, of course, used the rough assemblies of the human genome available at that time. This hampers the comparison and correlation with current human genome assemblies. Results: In the present work we identified and described in detail the distribution and genetic composition of 213 HERV-W elements. The bioinformatics analysis led to the characterization of several previously unreported features and provided a phylogenetic classification of two main subgroups with different age and structural characteristics. New facts on HERV-W genomic context of insertion and co-localization with sequences putatively involved in disease development are also reported. Conclusions: The present work is a detailed overview of the HERV-W contribution to the human genome and provides a robust genetic background useful to clarify HERV-W role in pathologies with poorly understood etiology, representing, to our knowledge, the most complete and exhaustive HERV-W dataset up to date. -

Hypermethylation of Genes in Testicular Embryonal Carcinomas

FULL PAPER British Journal of Cancer (2016) 114, 230–236 | doi: 10.1038/bjc.2015.408 Keywords: Embryonal carcinoma; DNA methylation; sex-linked genes; USP13; RBMY1A Hypermethylation of genes in testicular embryonal carcinomas Hoi-Hung Cheung*,1, Yanzhou Yang2, Tin-Lap Lee3, Owen Rennert4 and Wai-Yee Chan*,1,3 1The Chinese University of Hong Kong—Shandong University Joint Laboratory on Reproductive Genetics, School of Biomedical Sciences, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR; 2Key Laboratory of Fertility Preservation and Maintenance, Ministry of Education, Key Laboratory of Reproduction and Genetics in Ningxia, Ningxia Medical University, Ningxia 750004, China; 3Reproduction, Development and Endocrinology Theme, School of Biomedical Sciences, Faculty of Medicine, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Shatin, Hong Kong SAR and 4The Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD 20892, USA Background: Testicular embryonal carcinoma (EC) is a major subtype of non-seminomatous germ cell tumours in males. Embryonal carcinomas are pluripotent, undifferentiated germ cell tumours believed to originate from primordial germ cells. Epigenetic changes during testicular EC tumorigenesis require better elucidation. Methods: To identify epigenetic changes during testicular neoplastic transformation, we profiled DNA methylation of six ECs. These samples represent different stages (stage I and stage III) of divergent invasiveness. Non-cancerous testicular tissues were included. Expression of a number of hypermethylated genes were examined by quantitative RT-PCR and immunohis- tochemistry (IHC). Results: A total of 1167 tumour-hypermethylated differentially methylated regions (DMRs) were identified across the genome. Among them, 40 genes/ncRNAs were found to have hypermethylated promoters. -

Mrna Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats As Measured by Microarray Analysis

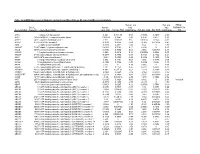

Table 3S: mRNA Expression in Human Leiomyoma and Eker Rats as Measured by Microarray Analysis Human_avg Rat_avg_ PENG_ Entrez. Human_ log2_ log2_ RAPAMYCIN Gene.Symbol Gene.ID Gene Description avg_tstat Human_FDR foldChange Rat_avg_tstat Rat_FDR foldChange _DN A1BG 1 alpha-1-B glycoprotein 4.982 9.52E-05 0.68 -0.8346 0.4639 -0.38 A1CF 29974 APOBEC1 complementation factor -0.08024 0.9541 -0.02 0.9141 0.421 0.10 A2BP1 54715 ataxin 2-binding protein 1 2.811 0.01093 0.65 0.07114 0.954 -0.01 A2LD1 87769 AIG2-like domain 1 -0.3033 0.8056 -0.09 -3.365 0.005704 -0.42 A2M 2 alpha-2-macroglobulin -0.8113 0.4691 -0.03 6.02 0 1.75 A4GALT 53947 alpha 1,4-galactosyltransferase 0.4383 0.7128 0.11 6.304 0 2.30 AACS 65985 acetoacetyl-CoA synthetase 0.3595 0.7664 0.03 3.534 0.00388 0.38 AADAC 13 arylacetamide deacetylase (esterase) 0.569 0.6216 0.16 0.005588 0.9968 0.00 AADAT 51166 aminoadipate aminotransferase -0.9577 0.3876 -0.11 0.8123 0.4752 0.24 AAK1 22848 AP2 associated kinase 1 -1.261 0.2505 -0.25 0.8232 0.4689 0.12 AAMP 14 angio-associated, migratory cell protein 0.873 0.4351 0.07 1.656 0.1476 0.06 AANAT 15 arylalkylamine N-acetyltransferase -0.3998 0.7394 -0.08 0.8486 0.456 0.18 AARS 16 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 5.517 0 0.34 8.616 0 0.69 AARS2 57505 alanyl-tRNA synthetase 2, mitochondrial (putative) 1.701 0.1158 0.35 0.5011 0.6622 0.07 AARSD1 80755 alanyl-tRNA synthetase domain containing 1 4.403 9.52E-05 0.52 1.279 0.2609 0.13 AASDH 132949 aminoadipate-semialdehyde dehydrogenase -0.8921 0.4247 -0.12 -2.564 0.02993 -0.32 AASDHPPT 60496 aminoadipate-semialdehyde