Interest-Rate Option Pricing Revisited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Master Thesis the Use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value an Empirical Study on European and Russian Non-Financial Firms

Master Thesis The use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value An empirical study on European and Russian non-financial firms Tilburg, October 5, 2014 Mark van Dijck, 937367 Tilburg University, Finance department Supervisor: Drs. J.H. Gieskens AC CCM QT Master Thesis The use of Interest Rate Derivatives and Firm Market Value An empirical study on European and Russian non-financial firms Tilburg, October 5, 2014 Mark van Dijck, 937367 Supervisor: Drs. J.H. Gieskens AC CCM QT 2 Preface In the winter of 2010 I found myself in the heart of a company where the credit crisis took place at that moment. During a treasury internship for Heijmans NV in Rosmalen, I experienced why it is sometimes unescapable to use interest rate derivatives. Due to difficult financial times, banks strengthen their requirements and the treasury department had to use different mechanism including derivatives to restructure their loans to the appropriate level. It was a fascinating time. One year later I wrote a bachelor thesis about risk management within energy trading for consultancy firm Tensor. Interested in treasury and risk management I have always wanted to finish my finance study period in this field. During the master thesis period I started to work as junior commodity trader at Kühne & Heitz. I want to thank Kühne & Heitz for the opportunity to work in the trading environment and to learn what the use of derivatives is all about. A word of gratitude to my supervisor Drs. J.H. Gieskens for his quick reply, well experienced feedback that kept me sharp to different levels of the subject, and his availability even in the late hours after I finished work. -

Calls, Puts and Select Alls

CIMA P3 SECTION D – MANAGING FINANCIAL RISK THE PUTS, THE CALLS AND THE DREADED ‘SELECT ALLs’ Example long form to OT approach Here is my favourite long form question on Interest rate risk management: Assume you are the Treasurer of AB, a large engineering company, and that it is now May 20X4. You have forecast that the company will need to borrow £2 million in September 20X4 for 6 months. The need for finance will arise because the company has extended its credit terms to selected customers over the summer period. The company’s bank currently charges customers such as AB plc 7.5% per annum interest for short-term unsecured borrowing. However, you believe interest rates will rise by at least 1.5 percentage points over the next 6 months. You are considering using one of four alternative methods to hedge the risk: (i) A traded interest rate option (cap only); or (ii) A traded interest rate option (cap and floor); or (iii) Forward rate agreements; or (iv) Interest rate futures; or You can purchase an interest rate cap at 93.00 for the duration of the loan to be guaranteed. You would have to pay a premium of 0.2% of the amount of the loan. For (ii) as part of the arrangement, the company can buy a traded floor at 94.00. Required: Discuss the features of using each of the four alternative methods of hedging the interest rate risk, apply to AB and advise on how each might be useful to AB, taking all relevant and known information into account. -

An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting

Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming John Jackson Ada Li Asani Sarkar Patricia Zobel Staff Report No. 557 March 2012 Revised October 2012 FRBNY Staff REPORTS This paper presents preliminary fi ndings and is being distributed to economists and other interested readers solely to stimulate discussion and elicit comments. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and are not necessarily refl ective of views at the Federal Reserve Bank of New York or the Federal Reserve System. Any errors or omissions are the responsibility of the authors. An Analysis of OTC Interest Rate Derivatives Transactions: Implications for Public Reporting Michael Fleming, John Jackson, Ada Li, Asani Sarkar, and Patricia Zobel Federal Reserve Bank of New York Staff Reports, no. 557 March 2012; revised October 2012 JEL classifi cation: G12, G13, G18 Abstract This paper examines the over-the-counter (OTC) interest rate derivatives (IRD) market in order to inform the design of post-trade price reporting. Our analysis uses a novel transaction-level data set to examine trading activity, the composition of market participants, levels of product standardization, and market-making behavior. We fi nd that trading activity in the IRD market is dispersed across a broad array of product types, currency denominations, and maturities, leading to more than 10,500 observed unique product combinations. While a select group of standard instruments trade with relative frequency and may provide timely and pertinent price information for market partici- pants, many other IRD instruments trade infrequently and with diverse contract terms, limiting the impact on price formation from the reporting of those transactions. -

Modeling VXX

Modeling VXX Sebastian A. Gehricke Department of Accountancy and Finance Otago Business School, University of Otago Dunedin 9054, New Zealand Email: [email protected] Jin E. Zhang Department of Accountancy and Finance Otago Business School, University of Otago Dunedin 9054, New Zealand Email: [email protected] First Version: June 2014 This Version: 13 September 2014 Keywords: VXX; VIX Futures; Roll Yield; Market Price of Variance Risk; Variance Risk Premium JEL Classification Code: G13 Modeling VXX Abstract We study the VXX Exchange Traded Note (ETN), that has been actively traded in the New York Stock Exchange in recent years. We propose a simple model for the VXX and derive an analytical expression for the VXX roll yield. The roll yield of any futures position is the return not due to movements of the underlying, in commodity futures it is often called the cost of carry. Using our model we confirm that the phenomena of the large negative returns of the VXX, as first documented by Whaley (2013), which we call the VXX return puzzle, is due to the predominantly negative roll yield as proposed but never quantified in the literature. We provide a simple and robust estimation of the market price of variance risk which uses historical VXX returns. Our VXX price model can be used to study the price of options written on the VXX. Modeling VXX 1 1 Introduction There are three major risk factors which are traded in financial markets: market risk which is traded in the stock market, interest rate risk which is traded in the bond markets and interest rate derivative markets, and volatility risk which up until recently was only traded indirectly in the options market. -

International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities

International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities Authors Dr. Jiri Strouhal Dr. Carmen Bonaci Editor Prof. Nikos Mastorakis Published by WSEAS Press ISBN: 9781-61804-008-4 www.wseas.org International Harmonization of Reporting for Financial Securities Published by WSEAS Press www.wseas.org Copyright © 2011, by WSEAS Press All the copyright of the present book belongs to the World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the Editor of World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Press. All papers of the present volume were peer reviewed by two independent reviewers. Acceptance was granted when both reviewers' recommendations were positive. See also: http://www.worldses.org/review/index.html ISBN: 9781-61804-008-4 World Scientific and Engineering Academy and Society Preface Dear readers, This publication is devoted to problems of financial reporting for financial instruments. This branch is among academicians and practitioners widely discussed topic. It is mainly caused due to current developments in financial engineering, while accounting standard setters still lag. Moreover measurement based on fair value approach – popular phenomenon of last decades – brings to accounting entities considerable problems. The text is clearly divided into four chapters. The introductory part is devoted to the theoretical background for the measurement and reporting of financial securities and derivative contracts. The second chapter focuses on reporting of equity and debt securities. There are outlined the theoretical bases for the measurement, and accounting treatment for selected portfolios of financial securities. -

Derivative Valuation Methodologies for Real Estate Investments

Derivative valuation methodologies for real estate investments Revised September 2016 Proprietary and confidential Executive summary Chatham Financial is the largest independent interest rate and foreign exchange risk management consulting company, serving clients in the areas of interest rate risk, foreign currency exposure, accounting compliance, and debt valuations. As part of its service offering, Chatham provides daily valuations for tens of thousands of interest rate, foreign currency, and commodity derivatives. The interest rate derivatives valued include swaps, cross currency swaps, basis swaps, swaptions, cancellable swaps, caps, floors, collars, corridors, and interest rate options in over 50 market standard indices. The foreign exchange derivatives valued nightly include FX forwards, FX options, and FX collars in all of the major currency pairs and many emerging market currency pairs. The commodity derivatives valued include commodity swaps and commodity options. We currently support all major commodity types traded on the CME, CBOT, ICE, and the LME. Summary of process and controls – FX and IR instruments Each day at 4:00 p.m. Eastern time, our systems take a “snapshot” of the market to obtain close of business rates. Our systems pull over 9,500 rates including LIBOR fixings, Eurodollar futures, swap rates, exchange rates, treasuries, etc. This market data is obtained via direct feeds from Bloomberg and Reuters and from Inter-Dealer Brokers. After the data is pulled into the system, it goes through the rates control process. In this process, each rate is compared to its historical values. Any rate that has changed more than the mean and related standard deviation would indicate as normal is considered an outlier and is flagged for further investigation by the Analytics team. -

Interest Rate Caps “Smile” Too! but Can the LIBOR Market Models Capture It?

Interest Rate Caps “Smile” Too! But Can the LIBOR Market Models Capture It? Robert Jarrowa, Haitao Lib, and Feng Zhaoc January, 2003 aJarrow is from Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 ([email protected]). bLi is from Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 ([email protected]). cZhao is from Department of Economics, Cornell University, Ithaca, NY 14853 ([email protected]). We thank Warren Bailey and seminar participants at Cornell University for helpful comments. We are responsible for any remaining errors. Interest Rate Caps “Smile” Too! But Can the LIBOR Market Models Capture It? ABSTRACT Using more than two years of daily interest rate cap price data, this paper provides a systematic documentation of a volatility smile in cap prices. We find that Black (1976) implied volatilities exhibit an asymmetric smile (sometimes called a sneer) with a stronger skew for in-the-money caps than out-of-the-money caps. The volatility smile is time varying and is more pronounced after September 11, 2001. We also study the ability of generalized LIBOR market models to capture this smile. We show that the best performing model has constant elasticity of variance combined with uncorrelated stochastic volatility or upward jumps. However, this model still has a bias for short- and medium-term caps. In addition, it appears that large negative jumps are needed after September 11, 2001. We conclude that the existing class of LIBOR market models can not fully capture the volatility smile. JEL Classification: C4, C5, G1 Interest rate caps and swaptions are widely used by banks and corporations for managing interest rate risk. -

Interest Rate Derivaties and Asset

ank participation in derivative markets has risen sharply in recent years. The total amotmt of interest rate, currency, commodity, and B equity contracts at U.S. commercial and savings banks soared from $6.8 trillion in 1990 to $11.9 trillion in 1993, an increase of 75 percent. A major concern facing policymakers and bank regulators today is the possibility that the rising use of derivatives has increased the riskiness of individual banks and of the banking system as a whole. Banks have long used one type of derivative instrument, namely interest rate futures, to manage interest rate risk (Koppenhaver 1986; Booth, Smith, and Stoltz 1984; Parkinson and Spindt 1986; Franckle and Senchack 1982). However, the development of newer instruments, such as swaps, caps, collars, and floors (see the glossary in Box 1), has greatly expanded the menu of financial technologies available to banks for asset-liability management. In particular, interest rate swaps have be- come the preferred tool. According to a recent market survey of deriva- tive users, 92 percent of responding financial institutions report using interest rate swaps to manage the interest rate risk of their lending portfolios (Group of Thirty 1993, pp. 40-41). Katerina Simons More recently, studies have focused on the determinants of the broader derivative activities of banks. Sinkey and Carter (1994) studied the determinants of bank use of derivatives between 1989 and 1991. They Economist, Federal Reserve Bank of found that measures of maturity gap and liquidity are consistently Boston. The author thanks Richard significant across banks of different asset sizes. Brewer, Minton and Kopcke, Willimn Lang, and the partic- Moser (1994) focused on the relationship between derivative use and ipants in the se~ninars at the Federal bank lending, concluding that the growth of business lending is posi- Reserve Bank of Boston, the meetings tively related to the presence of swaps on the bank’s books, though the of the Atlantic Economic Society, and presence of futures had no significant effect on bank lending. -

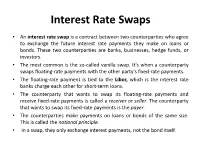

Interest Rate Swaps

Interest Rate Swaps • An interest rate swap is a contract between two counterparties who agree to exchange the future interest rate payments they make on loans or bonds. These two counterparties are banks, businesses, hedge funds, or investors. • The most common is the so-called vanilla swap. It's when a counterparty swaps floating-rate payments with the other party's fixed-rate payments. • The floating-rate payment is tied to the Libor, which is the interest rate banks charge each other for short-term loans. • The counterparty that wants to swap its floating-rate payments and receive fixed-rate payments is called a receiver or seller. The counterparty that wants to swap its fixed-rate payments is the payer. • The counterparties make payments on loans or bonds of the same size. This is called the notional principle. • In a swap, they only exchange interest payments, not the bond itself. • A smaller number of swaps are between two counter parties with floating- rate payments. • Also, the present value of the two payment streams must also be the same. That means that over the length of the bond, each counterparty will pay the same amount. It’s easy to calculate the NPV for the fixed-rate bond because the payment is always the same. It's more difficult to predict with the floating rate bond. The payment stream is based on Libor, which can change. Based on what they know today, both parties have to agree then on what they think will probably happen with interest rates. • A typical swap contract lasts for one to 15 years. -

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance

The Role of Interest Rate Swaps in Corporate Finance Anatoli Kuprianov n interest rate swap is a contractual agreement between two parties to exchange a series of interest rate payments without exchanging the A underlying debt. The interest rate swap represents one example of a general category of financial instruments known as derivative instruments. In the most general terms, a derivative instrument is an agreement whose value derives from some underlying market return, market price, or price index. The rapid growth of the market for swaps and other derivatives in re- cent years has spurred considerable controversy over the economic rationale for these instruments. Many observers have expressed alarm over the growth and size of the market, arguing that interest rate swaps and other derivative instruments threaten the stability of financial markets. Recently, such fears have led both legislators and bank regulators to consider measures to curb the growth of the market. Several legislators have begun to promote initiatives to create an entirely new regulatory agency to supervise derivatives trading activity. Underlying these initiatives is the premise that derivative instruments increase aggregate risk in the economy, either by encouraging speculation or by burdening firms with risks that management does not understand fully and is incapable of controlling.1 To be certain, much of this criticism is aimed at many of the more exotic derivative instruments that have begun to appear recently. Nevertheless, it is difficult, if not impossible, to appreciate the economic role of these more exotic instruments without an understanding of the role of the interest rate swap, the most basic of the new generation of financial derivatives. -

Term Structure Lattice Models

Term Structure Models: IEOR E4710 Spring 2005 °c 2005 by Martin Haugh Term Structure Lattice Models 1 The Term-Structure of Interest Rates If a bank lends you money for one year and lends money to someone else for ten years, it is very likely that the rate of interest charged for the one-year loan will di®er from that charged for the ten-year loan. Term-structure theory has as its basis the idea that loans of di®erent maturities should incur di®erent rates of interest. This basis is grounded in reality and allows for a much richer and more realistic theory than that provided by the yield-to-maturity (YTM) framework1. We ¯rst describe some of the basic concepts and notation that we need for studying term-structure models. In these notes we will often assume that there are m compounding periods per year, but it should be clear what changes need to be made for continuous-time models and di®erent compounding conventions. Time can be measured in periods or years, but it should be clear from the context what convention we are using. Spot Rates: Spot rates are the basic interest rates that de¯ne the term structure. De¯ned on an annual basis, the spot rate, st, is the rate of interest charged for lending money from today (t = 0) until time t. In particular, 2 mt this implies that if you lend A dollars for t years today, you will receive A(1 + st=m) dollars when the t years have elapsed. -

Derivative Instruments and Hedging Activities

www.pwc.com 2015 Derivative instruments and hedging activities www.pwc.com Derivative instruments and hedging activities 2013 Second edition, July 2015 Copyright © 2013-2015 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, a Delaware limited liability partnership. All rights reserved. PwC refers to the United States member firm, and may sometimes refer to the PwC network. Each member firm is a separate legal entity. Please see www.pwc.com/structure for further details. This publication has been prepared for general information on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice on facts and circumstances specific to any person or entity. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication. The information contained in this material was not intended or written to be used, and cannot be used, for purposes of avoiding penalties or sanctions imposed by any government or other regulatory body. PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, its members, employees and agents shall not be responsible for any loss sustained by any person or entity who relies on this publication. The content of this publication is based on information available as of March 31, 2013. Accordingly, certain aspects of this publication may be superseded as new guidance or interpretations emerge. Financial statement preparers and other users of this publication are therefore cautioned to stay abreast of and carefully evaluate subsequent authoritative and interpretative guidance that is issued. This publication has been updated to reflect new and updated authoritative and interpretative guidance since the 2012 edition.