FINDING PEDAGOGICAL STRATEGIES for COMBINED CLASSICAL and JAZZ SAXOPHONE APPLIED STUDIES at the COLLEGE LEVEL Ulf J

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tenor Saxophone Mouthpiece When

MAY 2014 U.K. £3.50 DOWNBEAT.COM MAY 2014 VOLUME 81 / NUMBER 5 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Davis Inman Contributing Editors Ed Enright Kathleen Costanza Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer Ara Tirado Bookkeeper Margaret Stevens Circulation Manager Sue Mahal Circulation Assistant Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Pete Fenech 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, David Kunian, Jennifer Odell; New York: Alan Bergman, Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Ira Gitler, Eugene Gologursky, Norm Harris, D.D. Jackson, Jimmy Katz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Richard Seidel, Tom Staudter, -

Julien Wilson: Improvisation and Timbral Manipulation on Selected Recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2020 Julien Wilson: Improvisation and timbral manipulation on selected recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio Maximillian Wickham Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Wickham, M. (2020). Julien Wilson: Improvisation and timbral manipulation on selected recordings with the Julien Wilson Trio. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1546 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1546 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": an Analytical Approach to Jazz

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2016 Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation DiSalvio, Nicholas Vincent, "Charles Ruggiero's "Tenor Attitudes": An Analytical Approach to Jazz Styles and Influences" (2016). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 1. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/1 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. CHARLES RUGGIERO’S “TENOR ATTITUDES”: AN ANALYTICAL APPROACH TO JAZZ STYLES AND INFLUENCES A Written Document Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in The School of Music by Nicholas Vincent DiSalvio B.M., Rowan University, 2009 M.M., Illinois State University, 2013 May 2016 For my wife Pagean: without you, I could not be where I am today. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my committee for their patience, wisdom, and guidance throughout the writing and revising of this document. I extend my heartfelt thanks to Dr. Griffin Campbell and Dr. Willis Delony for their tireless work with and belief in me over the past three years, as well as past professors Dr. -

Guest Artist Recital 2012–13 Season Thursday 1 November 2012 117Th Concert Dalton Center Lecture Hall 11:00 A.M

Guest Artist Recital 2012–13 Season Thursday 1 November 2012 117th Concert Dalton Center Lecture Hall 11:00 a.m. THE U.S. ARMY FIELD BAND SAXOPHONE QUARTET Staff Sergeant Daniel Goff, Soprano Saxophone Sergeant First Class Brian Sacawa, Alto Saxophone Sergeant First Class Chris Blossom, Tenor Saxophone Staff Sergeant David Parks, Baritone Saxophone Ludwig van Beethoven String Quartet Opus 18, Number 1 1770–1827 I. Allegro con brio arr. SFC Chris Blossom II. Adagio affettuso ed appassionato III. Allegro molto IV. Allegro Philip Glass Saxophone Quartet b. 1937 I. II. III. IV. Bobby Streng Beat Down b. 1980 If the fire alarm sounds, please exit the building im m ediately. A ll other em ergencies w ill be indicated by spoken announcem ent within the seating area. The tornado safe area in Dalton Center is along the lockers in the brick hallway to your left as you exit the Lecture Hall. In any emergency, walk—do not run—to the nearest exit. Please turn off all cell phones and other electronic devices during the performance. Because of legal issues, any video or audio recording of this performance is prohibited without prior consent from the School of Music. Thank you for your cooperation. THE U.S. ARMY FIELD BAND SAXOPHONE QUARTET is an official ensemble of the Musical Ambassadors of the Army. The quartet performs a wide range of repertoire including transcriptions, standard saxophone quartet literature, jazz and popular arrangements, and contemporary and avant-garde music. The ensemble seeks to present a program that displays the numerous stylistic and musical capabilities of the saxophone. -

Rutgers University Mason Gross School of the Arts Department of Music Undergraduate Student Handbook 2019-2020

Rutgers University Mason Gross School of the Arts Department of Music Undergraduate Student Handbook 2019-2020 2 Introduction The Mason Gross School of the Arts was established in 1976 as the arts conservatory of Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, and in 1981, the Department of Music joined the school. The department offers a comprehensive music program within the context of a public research university, and serves a diverse student body of approximately 500 graduate and undergraduate students from a wide range of specializations and backgrounds. The Mason Gross School of the Arts varied music degree programs share a common aim: to develop well- educated music professionals who have a thorough historical and theoretical understanding of all aspects of music. The purpose of this handbook is to provide basic information about the undergraduate degree programs offered through the Department of Music at the Rutgers University Mason Gross School of the Arts. Information, policies, and procedures included in this handbook are subject to change. The handbook will be updated on a yearly basis. Important: The degree requirements for an individual student are those that are in effect when the student begins the Bachelor of Music program or the Bachelor of Arts Music Major. Questions about information in this handbook should be directed to the Department of Music Undergraduate Advisor. Students are responsible for: Knowing information, policies, and procedures included in this handbook; Providing the Department of Music with up-to-date contact information; Regularly checking his/her assigned mailbox in the Marryott Music Building; Regularly checking his/her Rutgers email; personal email accounts should be linked to the Rutgers email account, and Referring to the “music major information” Sakai site for current announcements, information, and resources. -

The Saxophone Symposium: an Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2015 The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014 Ashley Kelly Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Kelly, Ashley, "The aS xophone Symposium: An Index of the Journal of the North American Saxophone Alliance, 1976-2014" (2015). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 2819. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/2819 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. THE SAXOPHONE SYMPOSIUM: AN INDEX OF THE JOURNAL OF THE NORTH AMERICAN SAXOPHONE ALLIANCE, 1976-2014 A Monograph Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and AgrIcultural and MechanIcal College in partIal fulfIllment of the requIrements for the degree of Doctor of MusIcal Arts in The College of MusIc and DramatIc Arts by Ashley DenIse Kelly B.M., UniversIty of Montevallo, 2008 M.M., UniversIty of New Mexico, 2011 August 2015 To my sIster, AprIl. II ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS My sIncerest thanks go to my committee members for theIr encouragement and support throughout the course of my research. Dr. GrIffIn Campbell, Dr. Blake Howe, Professor Deborah Chodacki and Dr. Michelynn McKnight, your tIme and efforts have been invaluable to my success. The completIon of thIs project could not have come to pass had It not been for the assIstance of my peers here at LouIsIana State UnIversIty. -

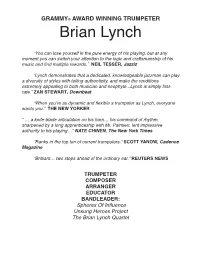

2013 Brian Lynch Full Press Kit(Bio-Discog

GRAMMY© AWARD WINNING TRUMPETER Brian Lynch “You can lose yourself in the pure energy of his playing, but at any moment you can switch your attention to the logic and craftsmanship of his music and find multiple rewards.” NEIL TESSER, Jazziz “Lynch demonstrates that a dedicated, knowledgeable jazzman can play a diversity of styles with telling authenticity, and make the renditions extremely appealing to both musician and neophyte...Lynch is simply first- rate.” ZAN STEWART, Downbeat “When you’re as dynamic and flexible a trumpeter as Lynch, everyone wants you.” THE NEW YORKER “ … a knife-blade articulation on his horn… his command of rhythm, sharpened by a long apprenticeship with Mr. Palmieri, lent impressive authority to his playing…” NATE CHINEN, The New York Times “Ranks in the top ten of current trumpeters.” SCOTT YANOW, Cadence Magazine “Brilliant… two steps ahead of the ordinary ear.” REUTERS NEWS TRUMPETER COMPOSER ARRANGER EDUCATOR BANDLEADER: Spheres Of Influence Unsung Heroes Project The Brian Lynch Quartet Brian Lynch "This is a new millennium, and a lot of music has gone down," Brian Lynch said several years ago. "I think that to be a jazz musician now means drawing on a wider variety of things than 30 or 40 years ago. Not to play a little bit of this or a little bit of that, but to blend everything together into something that has integrity and sounds good. Not to sound like a pastiche or shifting styles; but like someone with a lot of range and understanding." Trumpeter and Grammy© Award Winner Brian Lynch brings to his music an unparalleled depth and breadth of experience. -

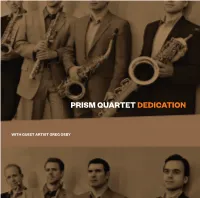

Prism Quartet Dedication

PRISM QUARTET DEDICATION WITH GUEST ARTIST GREG OSBY PRISM Quartet Dedication 1 Roshanne Etezady Inkling 1:09 2 Zack Browning Howler Back 1:09 3 Tim Ries Lu 2:36 4 Gregory Wanamaker speed metal organum blues 1:14 5 Renée Favand-See isolation 1:07 6 Libby Larsen Wait a Minute... 1:09 7 Nick Didkovksy Talea (hoping to somehow “know”) 1:06 8 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 1) 1:06 9 Nick Didkovksy Stink Up! (PolyPrism 2) 1:01 10 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo 11 Donnacha Dennehy Mild, Medium-Lasting, Artificial Happiness 1:49 12 Ken Ueno July 23, from sunrise to sunset, the summer of the S.E.P.S.A. bus rides destra e sinistra around Ischia just to get tomorrow’s scatolame 1:20 13 Adam B. Silverman Just a Minute, Chopin 2:21 14 William Bolcom Scherzino 1:16 Matthew Levy Three Miniatures 15 Diary 2:05 16 Meditation 1:49 17 Song without Words 2:33 PRISM Quartet/Music From China 3 18 Jennifer Higdon Bop 1:09 19 Dennis DeSantis Hive Mind 1:06 20 Robert Capanna Moment of Refraction 1:04 21 Keith Moore OneTwenty 1:31 22 Jason Eckardt A Fractured Silence 1:18 Frank J. Oteri Fair and Balanced? 23 Remaining Neutral 1:00 24 Seeming Partial 3:09 25 Uncommon Ground 1:00 26 Incremental Change 1:49 27 Perry Goldstein Out of Bounds 1:24 28 Tim Berne Brokelyn 0:57 29 Chen Yi Happy Birthday to PRISM 1:24 30 James Primosch Straight Up 1:24 31 Greg Osby Prism #1 (Refraction) (alternate take) 6:49 Greg Osby, alto sax solo TOTAL PLAYING TIME 57:53 All works composed and premiered in 2004 except Three Miniatures, composed/premiered in 2006. -

An Ultrasonographic Observation of Saxophonists' Tongue Positions

An Ultrasonographic Observation of Saxophonists’ Tongue Positions While Producing Front F Pitch Bends by Ryan C. Lemoine A Research Paper Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts Approved April 2016 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Joshua Gardner, Co-Chair Christopher Creviston, Co-Chair Sabine Feisst Robert Spring ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2016 ©2016 Ryan C. Lemoine All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Voicing, as it pertains to saxophone pedagogy, presents certain obstacles to both teachers and students simply because we cannot visually assess the internal mechanics of the vocal tract. The teacher is then left to instruct based on subjective “feel” which can lead to conflicting instruction, and in some cases, misinformation. In an effort to expand the understanding and pedagogical resources available, ten subjects—comprised of graduate-level and professional-level saxophonists— performed varied pitch bend tasks while their tongue motion was imaged ultrasonographically and recorded. Tongue range of motion was measured from midsagittal tongue contours extracted from the ultrasound data using a superimposed polar grid. The results indicate variations in how saxophonists shape their tongues in order to produce pitch bends from F6. i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to acknowledge and thank the saxophonist who volunteered their time to make this study possible. Also a special thanks to the members of my doctoral committee: Joshua Gardner, Christopher Creviston, Sabine Feisst, and Robert Spring. They have all been sources of encouragement and inspiration, not only during these final stages of my degree process, but for the duration of my studies at Arizona State University. -

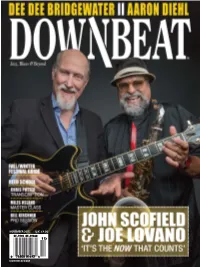

Downbeat.Com November 2015 U.K. £4.00

NOVEMBER 2015 2015 NOVEMBER U.K. £4.00 DOWNBEAT.COM DOWNBEAT JOHN SCOFIELD « DEE DEE BRIDGEWATER « AARON DIEHL « ERIK FRIEDLANDER « FALL/WINTER FESTIVAL GUIDE NOVEMBER 2015 NOVEMBER 2015 VOLUME 82 / NUMBER 11 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Associate Editor Brian Zimmerman Contributing Editor Ed Enright Art Director LoriAnne Nelson Contributing Designer ĺDQHWDÎXQWRY£ Circulation Manager Kevin R. Maher Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes Bookkeeper Emeritus Margaret Stevens Editorial Assistant Stephen Hall Editorial Intern Baxter Barrowcliff ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile 630-941-2030 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney 201-445-6260 [email protected] Classified Advertising Sales Sam Horn 630-941-2030 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Austin: Kevin Whitehead; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank- John Hadley; Chicago: John Corbett, Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Mitch Myers, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Denver: Norman Provizer; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Iowa: Will Smith; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Todd Jenkins, Kirk Silsbee, Chris Walker, Joe Woodard; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Robin James; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; -

(Incorporated 1990) Offers Books and Cds

Saxophone Catalog 21 Van Cott Information Services, Inc. 5/13/21 presents Saxophone Music, Books, CDs and More This catalog includes saxophone books, videos, and CDs; reed books; woodwind books; and general music books. We are happy to accept Purchase Orders from University Music Departments, Libraries and Bookstores in the US. We also have clarinet, flute, oboe, and bassoon books, videos and CDs. You may order online, by fax, or phone. To order or for the latest information visit our web site at http://www.vcisinc.com. Bindings: HB: Hard Bound, PB: Perfect Bound (paperback with square spine), SS: Saddle Stitch (paper, folded and stapled), SB: Spiral Bound (plastic or metal). Shipping: Heavy item, US Media Mail shipping charges based on weight. Free US Media Mail shipping on this item if ordered with another item with paid shipping. Price and Availability Subject to Change. Table of Contents S995. Londeix Guide to the Saxophone Repertoire Saxophone Books .................................................................. 1 1844-2012 edited by Bruce Ronkin. Roncorp Publica- tions, 2012, HB, 776 pages. The latest version of this book Saxophone Jazz Books........................................................... 3 is 130 pages longer than the previous edition. It is in French Saxophone Music .................................................................. 3 and English. More than 29,000 works for saxophone from Excerpts ....................................................................... 3 1844 to 2012–the entire lifespan of the saxophone–are -

Department of Music Programs 1999 - 2000 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University

Olivet Nazarene University Digital Commons @ Olivet School of Music: Performance Programs Music 2000 Department of Music Programs 1999 - 2000 Department of Music Olivet Nazarene University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog Part of the Fine Arts Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Department of Music, "Department of Music Programs 1999 - 2000" (2000). School of Music: Performance Programs. 33. https://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/musi_prog/33 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Music at Digital Commons @ Olivet. It has been accepted for inclusion in School of Music: Performance Programs by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Olivet. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Department of Music Music Programs 1999-2000 Olivet Nazarene University Olivet Nazarene University Department of Music presen ts O PUS 3 Faculty Piano Trio Gerald Anderson, piano Sarah Morris, violin Daniel Gasse, cello Thursday, September 2, 1999 Kresge Auditorium 7:30 p.m. PROGRAM Trio Sonata in B minor J. B. Loeillet Largo (1653-1728) Allegro Adagio Allegro con spirito Trio #2 in B minor, op. 76 J. Turina Lento-Allegro molto moderato (1882-1949) Molto vivace Lento-Andante mosso INTERMISSION Trio #1 in B minor, op. 49 F. Mendelssohn Molto allegro ed agitato (1809-1847) Andante con moto tranquillo Leggiero e vivace Allegro assai appassionato OPUS 3 is a piano trio composed of faculty members at Olivet Nazarene University. It includes Dr. Gerald Anderson playing the piano, Dr. Daniel Gasse performing on the cello, and Ms. Sarah Morris playing the violin. ------------------ Dr.