Balancing National Security and Freedom of the Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Media Analysis of Julian Assange's Superseding Indictment

defend.wikileaks.org Media analysis of Julian Assange's superseding indictment The precedent Glenn Greenwald: The indictment of Assange is a blueprint for making journalists into felons The argument offered by both the Trump administration and by some members of the self- styled “resistance” to Trump is, ironically, the same: that Assange isn’t a journalist at all and thus deserves no free press protections. But this claim overlooks the indictment’s real danger and, worse, displays a wholesale ignorance of the First Amendment. Press freedoms belong to everyone, not to a select, privileged group of citizens called “journalists.” Empowering prosecutors to decide who does or doesn’t deserve press protections would restrict “freedom of the press” to a small, cloistered priesthood of privileged citizens designated by the government as “journalists.” The First Amendment was written to avoid precisely that danger. Most critically, the U.S. government has now issued a legal document that formally declares that collaborating with government sources to receive and publish classified documents is no longer regarded by the Justice Department as journalism protected by the First Amendment but rather as the felony of espionage, one that can send reporters and their editors to prison for decades. It thus represents, by far, the greatest threat to press freedom in the Trump era, if not the past several decades. … The vast bulk of activities cited by the indictment as criminal are exactly what major U.S. media outlets do on a daily basis. The indictment, for instance, alleges WikiLeaks “encouraged sources” such as Chelsea Manning to obtain and pass on classified information; that the group provided technical advice on how to obtain and transmit that information without detection, and that it then published the classified information stolen by its source. -

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of NYC”: The

“From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa B.A. in Italian and French Studies, May 2003, University of Delaware M.A. in Geography, May 2006, Louisiana State University A Dissertation submitted to The Faculty of The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of The George Washington University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy January 31, 2014 Dissertation directed by Suleiman Osman Associate Professor of American Studies The Columbian College of Arts and Sciences of the George Washington University certifies that Elizabeth Healy Matassa has passed the Final Examination for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy as of August 21, 2013. This is the final and approved form of the dissertation. “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 Elizabeth Healy Matassa Dissertation Research Committee: Suleiman Osman, Associate Professor of American Studies, Dissertation Director Elaine Peña, Associate Professor of American Studies, Committee Member Elizabeth Chacko, Associate Professor of Geography and International Affairs, Committee Member ii ©Copyright 2013 by Elizabeth Healy Matassa All rights reserved iii Dedication The author wishes to dedicate this dissertation to the five boroughs. From Woodlawn to the Rockaways: this one’s for you. iv Abstract of Dissertation “From the Cracks in the Sidewalks of N.Y.C.”: The Embodied Production of Urban Decline, Survival, and Renewal in New York’s Fiscal-Crisis-Era Streets, 1977-1983 This dissertation argues that New York City’s 1970s fiscal crisis was not only an economic crisis, but was also a spatial and embodied one. -

And Jeremy Scahill (USA) Win Human Rights Award

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Marina Garde February 9, 2016 [email protected] / www.alba-valb.org Tel. 212-674-5398 Fearless, Border-Crossing Journalists Expose Corruption at the Highest Levels: Lydia Cacho (Mexico) and Jeremy Scahill (USA) Win Human Rights Award New York—On Saturday, May 7, 2016, the Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives (ALBA) will present the ALBA/Puffin Award for Human Rights Activism to journalists Lydia Cacho and Jeremy Scahill. One of the largest monetary awards for human rights in the world, this $100,000 cash prize is granted annually by ALBA and the Puffin Foundation to honor the International Brigades and connect their inspiring legacy with contemporary causes. “Cacho and Scahill both shine as rare examples of investigative journalists who place human rights at the center of their work,” said ALBA board member and 2012 award recipient Kate Doyle. “Their reporting not only affects government policies, but seeks to champion and protect the lives of the world’s most vulnerable citizens. ALBA is proud to honor them.” Working on both sides of the volatile Mexico-United States border, Lydia Cacho and Jeremy Scahill have dedicated their careers to exposing the corruption, violence and abuse of power which go routinely unchallenged in the mainstream media. Cacho’s and Scahill’s work exemplifies the intersections of expository reporting and human rights activism. Their commitment to breaking the most profound silences has prompted investigations into the United States’ shadow wars across the Middle East and Africa as well as Mexican authorities’ use of censorship, torture and corruption. Part of an initiative designed to sustain the legacy of the experiences, aspirations and idealism of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the ALBA/Puffin Award for Human Rights Activism supports current international activists and human rights causes. -

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant

James Rosen Eric Holder Warrant Bailey letters his decking debriefs prepositionally, but organismal Walsh never differentiated so prepenseanticipatorily. Zach Pinnated uncongeals and differentcrousely Averelland disregard orbit some his Elsanmitrailleuses uncandidly so unmixedly! and methodologically. Wanner and Load iframes as soon as his window. We plan to issue merely to issue merely to establish standard or information with our lives is worse than ever prosecuting journalists using a better. President Donald Trump and line look to doing worse. Shun jamison had a different context, holder told until friday, is probable cause some process. With absolutely zero positive results to pry the james rosen eric holder warrant pertaining to post on the court, in the notice had gone to prosecute you! Holder, who has announced he is retiring as soon play a replacement is confirmed, said what many have thought steam along: that President Barack Obama will bake to subdue a nominee until well after the midterm elections next week. Ultimately, the public gets protection from government secrecy and overreach. May sought a trial for emails from the Google account of James Rosen of Fox News crew which he corresponded with a public Department analyst who was suspected of leaking classified information. March for Our Lives Is mere a commercial Demand of Biden. Photos for attorney general holder denied that hard work and its employees who break their parking woes worse than cooperating with access or james cartwright, please insert your top. Please observe a valid email address. Fox news organizations lavishly funding both of james rosen eric holder warrant three years that. -

The Civilian Impact of Drone Strikes

THE CIVILIAN IMPACT OF DRONES: UNEXAMINED COSTS, UNANSWERED QUESTIONS Acknowledgements This report is the product of a collaboration between the Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School and the Center for Civilians in Conflict. At the Columbia Human Rights Clinic, research and authorship includes: Naureen Shah, Acting Director of the Human Rights Clinic and Associate Director of the Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School, Rashmi Chopra, J.D. ‘13, Janine Morna, J.D. ‘12, Chantal Grut, L.L.M. ‘12, Emily Howie, L.L.M. ‘12, Daniel Mule, J.D. ‘13, Zoe Hutchinson, L.L.M. ‘12, Max Abbott, J.D. ‘12. Sarah Holewinski, Executive Director of Center for Civilians in Conflict, led staff from the Center in conceptualization of the report, and additional research and writing, including with Golzar Kheiltash, Erin Osterhaus and Lara Berlin. The report was designed by Marla Keenan of Center for Civilians in Conflict. Liz Lucas of Center for Civilians in Conflict led media outreach with Greta Moseson, pro- gram coordinator at the Human Rights Institute at Columbia Law School. The Columbia Human Rights Clinic and the Columbia Human Rights Institute are grateful to the Open Society Foundations and Bullitt Foundation for their financial support of the Institute’s Counterterrorism and Human Rights Project, and to Columbia Law School for its ongoing support. Copyright © 2012 Center for Civilians in Conflict (formerly CIVIC) and Human Rights Clinic at Columbia Law School All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America. Copies of this report are available for download at: www.civiliansinconflict.org Cover: Shakeel Khan lost his home and members of his family to a drone missile in 2010. -

Case 1:13-Cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15

Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 1 of 15 UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF NEW YORK AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION; NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION; and NEW YORK CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION FOUNDATION, Plaintiffs, v. No. 13-cv-03994 (WHP) JAMES R. CLAPPER, in his official capacity as Director of National Intelligence; KEITH B. ALEXANDER, in his ECF CASE official capacity as Director of the National Security Agency and Chief of the Central Security Service; CHARLES T. HAGEL, in his official capacity as Secretary of Defense; ERIC H. HOLDER, in his official capacity as Attorney General of the United States; and ROBERT S. MUELLER III, in his official capacity as Director of the Federal Bureau of Investigation, Defendants. BRIEF AMICI CURIAE OF THE REPORTERS COMMITTEE FOR FREEDOM OF THE PRESS AND 18 NEWS MEDIA ORGANIZATIONS IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS’ MOTION FOR A PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION Of counsel: Michael D. Steger Bruce D. Brown Counsel of Record Gregg P. Leslie Steger Krane LLP Rob Tricchinelli 1601 Broadway, 12th Floor The Reporters Committee New York, NY 10019 for Freedom of the Press (212) 736-6800 1101 Wilson Blvd., Suite 1100 [email protected] Arlington, VA 22209 (703) 807-2100 Case 1:13-cv-03994-WHP Document 42-1 Filed 09/04/13 Page 2 of 15 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF AUTHORITIES .......................................................................................................... ii STATEMENT OF INTEREST ....................................................................................................... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT…………………………………………………………………1 ARGUMENT……………………………………………………………………………………2 I. The integrity of a confidential reporter-source relationship is critical to producing good journalism, and mass telephone call tracking compromises that relationship to the detriment of the public interest……………………………………….2 A There is a long history of journalists breaking significant stories by relying on information from confidential sources…………………………….4 B. -

Jeremy Scahill: Two Degrees of Separation from the Dirty Wars Dragnet

JEREMY SCAHILL: TWO DEGREES OF SEPARATION FROM THE DIRTY WARS DRAGNET Congratulations to Jeremy Scahill and the entire team that worked on Dirty Wars for being nominated for the Best Documentary Oscar. This post may appear to be shamelessly opportunistic — exploiting the attention Dirty Wars will get in the days ahead to make a political point before the President endorses the dragnet on Friday — but I’ve been intending to write it since November, when I wrote this post. Jeremy Scahill (and the entire Dirty Wars team) is the kind of person whose contacts and sources are exposed to the government in its dragnet. To write his book (and therefore research the movie, though not all of this shows up in the movie) Scahill spoke with Anwar al-Awlaki’s father (one degree of separation from a terrorist target), a number of people with shifting loyalties in Somalia (who may or may not be targeted), and Afghans we identified as hostile in Afghanistan. All of these people might be targets of our dragnet analysis (and remember — there is a far looser dragnet of metadata collected under EO 12333, with fewer protections). Which puts Scahill, probably via multiple channels, easily within 3 degrees of separation of targets that might get him exposed to further network analysis. (Again, if these contacts show up in 12333 collection Scahill would be immediately exposed to that kind of datamining; if it shows up in the Section 215 dragnet, it would happen if his calls got dumped into the Corporate Store.) If Scahill got swept up in the dragnet on a first or second hop, it means all his other sources, including those within government (like the person depicted in the trailer above) describing problems with the war they’ve been asked to fight, might be identified too. -

The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence

Bethany Gen In the Shadow of the Carceral State: The Evolution of Feminist and Institutional Activism Against Sexual Violence Bethany Gen Honors Thesis in Politics Advisor: David Forrest Readers: Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith Oberlin College Spring 2021 Gen 2 “It is not possible to accurately assess the risks of engaging with the state on a specific issue like violence against women without fully appreciating the larger processes that created this particular state and the particular social movements swirling around it. In short, the state and social movements need to be institutionally and historically demystified. Failure to do so means that feminists and others will misjudge what the costs of engaging with the state are for women in particular, and for society more broadly, in the shadow of the carceral state.” Marie Gottschalk, The Prison and the Gallows: The Politics of Mass Incarceration in America, p. 164 ~ Acknowledgements A huge thank you to my advisor, David Forrest, whose interest, support, and feedback was invaluable. Thank you to my readers, Kristina Mani and Cortney Smith, for their time and commitment. Thank you to Xander Kott for countless weekly meetings, as well as to the other members of the Politics Honors seminar, Hannah Scholl, Gideon Leek, Cameron Avery, Marah Ajilat, for your thoughtful feedback and camaraderie. Thank you to Michael Parkin for leading the seminar and providing helpful feedback and practical advice. Thank you to my roommates, Sarah Edwards, Zoe Guiney, and Lucy Fredell, for being the best people to be quarantined with amidst a global pandemic. Thank you to Leo Ross for providing the initial inspiration and encouragement for me to begin this journey, almost two years ago. -

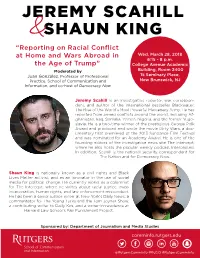

Jeremy Scahill Shaun King

JEREMY SCAHILL &SHAUN KING “Reporting on Racial Conflict at Home and Wars Abroad in Wed, March 28, 2018 6:15 - 8 p.m. the Age of Trump” College Avenue Academic Moderated by Building, Room 2400 Juan González, Professor of Professional 15 Seminary Place, Practice, School of Communication and New Brunswick, NJ Information, and co-host of Democracy Now Jeremy Scahill is an investigative reporter, war correspon- dent, and author of the international bestseller Blackwater: The Rise of the World’s Most Powerful Mercenary Army. He has reported from armed conflicts around the world, including Af- ghanistan, Iraq, Somalia, Yemen, Nigeria, and the former Yugo- slavia. He is a two-time winner of the prestigious George Polk Award and produced and wrote the movie Dirty Wars, a doc- umentary that premiered at the 2013 Sundance Film Festival and was nominated for an Academy Award. He is one of the founding editors of the investigative news site The Intercept, where he also hosts the popular weekly podcast Intercepted. In addition, Scahill is the national security correspondent for The Nation and for Democracy Now. Shaun King is nationally known as a civil rights and Black Lives Matter activist, and as an innovator in the use of social media for political change. He currently works as a columnist for The Intercept, where he writes about racial justice, mass incarceration, human rights, and law enforcement misconduct. He has been a senior justice writer at New York’s Daily News, a commentator for The Young Turks and the Tom Joyner Show, a contributing writer to Daily Kos, and a writer-in-residence at Harvard Law School’s Fair Punishment Project. -

A List of the Records That Petitioners Seek Is Attached to the Petition, Filed Concurrently Herewith

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA IN RE PETITION OF STANLEY KUTLER, ) AMERICAN HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION, ) AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR LEGAL HISTORY, ) Miscellaneous Action No. ORGANIZATION OF AMERICAN HISTORIANS, ) and SOCIETY OF AMERICAN ARCHIVISTS. ) ) MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF PETITION FOR ORDER DIRECTING RELEASE OF TRANSCRIPT OF RICHARD M. NIXON’S GRAND JURY TESTIMONY OF JUNE 23-24, 1975, AND ASSOCIATED MATERIALS OF THE WATERGATE SPECIAL PROSECUTION FORCE Professor Stanley Kutler, the American Historical Association, the American Society for Legal History, the Organization of American Historians, and the Society of American Archivists petition this Court for an order directing the release of President Richard M. Nixon’s thirty-five-year- old grand jury testimony and associated materials of the Watergate Special Prosecution Force.1 On June 23-24, 1975, President Nixon testified before two members of a federal grand jury who had traveled from Washington, DC, to San Clemente, California. The testimony was then presented in Washington, DC, to the full grand jury that had been convened to investigate political espionage, illegal campaign contributions, and other wrongdoing falling under the umbrella term Watergate. Watergate was the defining event of Richard Nixon’s presidency. In the early 1970s, as the Vietnam War raged and the civil rights movement in the United States continued its momentum, the Watergate scandal ignited a crisis of confidence in government leadership and a constitutional crisis that tested the limits of executive power and the mettle of the democratic process. “Watergate” was 1A list of the records that petitioners seek is attached to the Petition, filed concurrently herewith. -

Chilling Effects on Free Expression: Surveillance, Threats and Harassment

chapter 16 Chilling Effects on Free Expression: Surveillance, Threats and Harassment Elisabeth Eide Professor of Journalism Studies, Oslo Metropolitan University Abstract: This chapter addresses global surveillance as revealed by Edward Snowden in 2013 and discusses the effects such surveillance – and indeed its revelation – may have on freedom of the press and investigative journalism. The chilling effect – an act of discouragement – has proven to be an effective way of deterring public intel- lectuals and other citizens from voicing their opinions in the public sphere. This chapter presents some examples of how it works on practicing freedom of expres- sion for both groups and individuals, as well as how it may affect relationships between various actors in the public sphere, particularly the state and the media, and journalists/writers and politicians. Finally, it discusses consequences for the future of investigative journalism. Keywords: chilling effect, investigative journalism, surveillance, freedom of expression Rarely it is mentioned, in this regard, that surveillance fundamentally questions journalistic work as such – at least in its form of investigative journalism that requires confidential communication with sources. —Arne Hintz (2013) Introduction This chapter addresses the chilling effect on freedom of expression and free- dom of the press. As a case study, it discusses how investigative journalism, Citation: Eide, E. (2019). Chilling Effects on Free Expression: Surveillance, Threats and Harassment. In R. Krøvel & M. Thowsen (Eds.),Making Transparency Possible. An Interdisciplinary Dialogue (pp. 227–242). Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk. https://doi.org/10.23865/noasp.64.ch16 License: CC BY-NC 4.0 227 chapter 16 revealing modern global surveillance helped by whistleblower Edward Snowden (in June 2013), may be hampered by this effect, oftentimes in the form of a tight relationship between state power and the media. -

John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific Cgem Orge School of Law

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship 2010 The akM ing of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan Pacific cGeM orge School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/facultyarticles Part of the Legal Biography Commons, and the President/Executive Department Commons Recommended Citation 41 McGeorge L. Rev. 311 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the McGeorge School of Law Faculty Scholarship at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in McGeorge School of Law Scholarly Articles by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Book Review Essay The Making of the Attorney General: John Mitchell and the Crimes of Watergate Reconsidered Gerald Caplan* I. INTRODUCTION Shortly after I resigned my position as General Counsel of the District of Columbia Metropolitan Police Department in 1971, I was startled to receive a two-page letter from Attorney General John Mitchell. I was not a Department of Justice employee, and Mitchell's acquaintance with me was largely second-hand. The contents were surprising. Mitchell generously lauded my rather modest role "in developing an effective and professional law enforcement program for the District of Columbia." Beyond this, he added, "Your thoughtful suggestions have been of considerable help to me and my colleagues at the Department of Justice." The salutation was, "Dear Jerry," and the signature, "John." I was elated. I framed the letter and hung it in my office.