A Study of Linguistic Strategies in Irish Dáil Debates with a Focus on Power and Gender

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Brochure: Ireland's Meps 2019-2024 (EN) (Pdf 2341KB)

Clare Daly Deirdre Clune Luke Ming Flanagan Frances Fitzgerald Chris MacManus Seán Kelly Mick Wallace Colm Markey NON-ALIGNED Maria Walsh 27MEPs 40MEPs 18MEPs7 62MEPs 70MEPs5 76MEPs 14MEPs8 67MEPs 97MEPs Ciarán Cuffe Barry Andrews Grace O’Sullivan Billy Kelleher HHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHHH Printed in November 2020 in November Printed MIDLANDS-NORTH-WEST DUBLIN SOUTH Luke Ming Flanagan Chris MacManus Colm Markey Group of the European United Left - Group of the European United Left - Group of the European People’s Nordic Green Left Nordic Green Left Party (Christian Democrats) National party: Sinn Féin National party: Independent Nat ional party: Fine Gael COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: • Budgetary Control • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Agriculture and Rural Development • Economic and Monetary Affairs (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism Midlands - North - West West Midlands - North - • International Trade (substitute member) • Fisheries (substitute member) Barry Andrews Ciarán Cuffe Clare Daly Renew Europe Group Group of the Greens / Group of the European United Left - National party: Fianna Fáil European Free Alliance Nordic Green Left National party: Green Party National party: Independents Dublin COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: COMMITTEES: for change • International Trade • Industry, Research and Energy • Civil Liberties, Justice and Home Affairs • Development (substitute member) • Transport and Tourism • International Trade (substitute member) • Foreign Interference in all Democratic • -

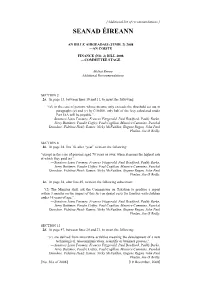

Seanad Éireann

[Additional list of recommendations.] SEANAD ÉIREANN AN BILLE AIRGEADAIS (UIMH. 2) 2008 —AN COISTE FINANCE (NO. 2) BILL 2008 —COMMITTEE STAGE Moltaí Breise Additional Recommendations SECTION 2 2a. In page 13, between lines 10 and 11, to insert the following: “(d) in the case of persons whose income only exceeds the threshold set out in paragraphs (a) and (c) by €10,000, only half of the levy calculated under Part 18A will be payable.”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. SECTION 8 2b. In page 38, line 18, after “year” to insert the following: “except in the case of persons aged 70 years or over, when it means the highest rate at which they paid tax”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. 2c. In page 38, after line 45, to insert the following subsection: “(2) The Minister shall ask the Commission on Taxation to produce a report within 3 months on the impact of this Act on dental costs for families with children under 16 years of age.”. —Senators Liam Twomey, Frances Fitzgerald, Paul Bradford, Paddy Burke, Jerry Buttimer, Paudie Coffey, Paul Coghlan, Maurice Cummins, Paschal Donohoe, Fidelma Healy Eames, Nicky McFadden, Eugene Regan, John Paul Phelan, Joe O’Reilly. SECTION 13 2d. In page 47, between lines 20 and 21, to insert the following: “(c) are derived from innovative activities meaning the development of a new technological, telecommunication, scientific or business process,”. -

Dáil Éireann

DÁIL ÉIREANN AN BILLE OIDHREACHTA, 2016 HERITAGE BILL 2016 LEASUITHE TUARASCÁLA REPORT AMENDMENTS [No. 2c of 2016] [2 July, 2018] DÁIL ÉIREANN AN BILLE OIDHREACHTA, 2016 —AN TUARASCÁIL HERITAGE BILL 2016 —REPORT Leasuithe Amendments 1. In page 4, lines 18 and 19, to delete all words from and including “These” in line 18 down to and including line 19. —An tAire Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta. 2. In page 4, lines 35 to 37, to delete all words from and including ", subject” in line 35 down to and including “for” in line 37. —An tAire Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta. 3. In page 4, line 38, after “canals” to insert the following: “, within agreed procedures on a temporary basis due to an emergency or to facilitate a planned event or maintain and upgrade”. —Éamon Ó Cuív. 4. In page 5, line 3, after “permits” to insert “(for mooring and passage by boats)”. —Éamon Ó Cuív. 5. In page 5, to delete lines 27 to 29 and substitute the following: “(p) the charging and fixing of fees, tolls and charges in respect of the use by boats of the canals (including the use of locks on the canals and mooring on the canals) and the charging and fixing of fees in respect of the use by persons of the canals (including the taking of water from the canals);”. —An tAire Cultúir, Oidhreachta agus Gaeltachta. 6. In page 5, line 40, to delete “and” and substitute the following: “(ii) develop a system whereby interested parties can register electronically with Waterways Ireland and be notified automatically of all bye-laws proposed to be made, and”. -

European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast

Briefing May 2019 European Parliament Elections 2019 - Forecast Austria – 18 MEPs Staff lead: Nick Dornheim PARTIES (EP group) Freedom Party of Austria The Greens – The Green Austrian People’s Party (ÖVP) (EPP) Social Democratic Party of Austria NEOS – The New (FPÖ) (Salvini’s Alliance) – Alternative (Greens/EFA) – 6 seats (SPÖ) (S&D) - 5 seats Austria (ALDE) 1 seat 5 seats 1 seat 1. Othmar Karas* Andreas Schieder Harald Vilimsky* Werner Kogler Claudia Gamon 2. Karoline Edtstadler Evelyn Regner* Georg Mayer* Sarah Wiener Karin Feldinger 3. Angelika Winzig Günther Sidl Petra Steger Monika Vana* Stefan Windberger 4. Simone Schmiedtbauer Bettina Vollath Roman Haider Thomas Waitz* Stefan Zotti 5. Lukas Mandl* Hannes Heide Vesna Schuster Olga Voglauer Nini Tsiklauri 6. Wolfram Pirchner Julia Elisabeth Herr Elisabeth Dieringer-Granza Thomas Schobesberger Johannes Margreiter 7. Christian Sagartz Christian Alexander Dax Josef Graf Teresa Reiter 8. Barbara Thaler Stefanie Mösl Maximilian Kurz Isak Schneider 9. Christian Zoll Luca Peter Marco Kaiser Andrea Kerbleder Peter Berry 10. Claudia Wolf-Schöffmann Theresa Muigg Karin Berger Julia Reichenhauser NB 1: Only the parties reaching the 4% electoral threshold are mentioned in the table. Likely to be elected Unlikely to be elected or *: Incumbent Member of the NB 2: 18 seats are allocated to Austria, same as in the previous election. and/or take seat to take seat, if elected European Parliament ••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••••• www.eurocommerce.eu Belgium – 21 MEPs Staff lead: Stefania Moise PARTIES (EP group) DUTCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY FRENCH SPEAKING CONSITUENCY GERMAN SPEAKING CONSTITUENCY 1. Geert Bourgeois 1. Paul Magnette 1. Pascal Arimont* 2. Assita Kanko 2. Maria Arena* 2. -

Parliamentary Scorecard 2009 – 2010

PARLIAMENTARY SCORECARD 2009 – 2010 ASSESSING THE PERFORMANCE OF UGANDA’S LEGISLATORS Parliamentary Scorecard 2009 – 2010: Assessing the Performance of Uganda’s Legislators A publication of the Africa Leadership Institute with technical support from Projset Uganda, Stanford University and Columbia University. Funding provided by the Royal Netherlands Embassy in Uganda and Deepening Democracy Program. All rights reserved. Published January 2011. Design and Printing by Some Graphics Ltd. Tel: +256 752 648576; +256 776 648576 Africa Leadership Institute For Excellence in Governance, Security and Development P.O. Box 232777 Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256 414 578739 Plot 7a Naguru Summit View Road Email: [email protected] 1 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Acknowledgements 3 II. Abbreviations 6 III. Forward 7 IV. Executive Summary 9 V. Report on the Parliamentary Performance Scorecard 13 1. Purpose 13 2. The Road to the 2009 – 2010 Scorecard 14 2.1 Features of the 2009 – 2010 Scorecard 15 3. Disseminating the Scorecard to Voters through Constituency Workshops 17 4. Data Sources 22 5. Measures 22 A. MP Profile 23 B. Overall Grades for Performance 25 C. Disaggregated Performance Scores 29 Plenary Performance 29 Committee Performance 34 Constituency Performance 37 Non-Graded Measures 37 D. Positional Scores 40 Political Position 40 Areas of Focus 42 MP’s Report 43 6. Performance of Parliament 43 A. Performance of Sub-Sections of Parliament 43 B. How Does MP Performance in 2009 – 2010 Compare to Performance in the Previous Three Years of the 8th Parliament? 51 Plenary Performance 51 Committee Performance 53 Scores Through the Years 54 C. Parliament’s Productivity 55 7. -

Dáil Éireann: the First 100 Years, 1919–2019

Dáil Éireann: the first 100 years, 1919–2019 A commemoration of the first 100 years of Dáil Éireann 11 December 2018 at the Royal Irish Academy 08:30 Registration 09:00 Welcome: Michael Peter Kennedy, President, Royal Irish Academy Introduction: Seán Ó Fearghaíl, TD, Ceann Comhairle 09:30 Panel one—Origins and Consolidation: 1919–45 Chair: Stephen Collins, journalist and author Panellists: Marie Coleman, School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen’s University Belfast Bill Kissane, Department of Government, London School of Economics Michael Laffan, School of History, University College Dublin Ciara Meehan, School of Humanities, University of Hertfordshire 11:00 Tea/Coffee 11:30 Panel two—Evolution and Developments: 1945–present Chair: Olivia O’Leary, journalist and broadcaster Panellists: Brigid Laffan, MRIA, Robert Schuman Centre, European University Institute, Florence Martin Mansergh, MRIA, Vice-Chair, Decade of Centenaries Expert Group Fearghal McGarry, School of History, Anthropology, Philosophy and Politics, Queen’s University Belfast Theresa Reidy, Department of Government and Politics, University College Cork 13:00 Lunch 14:00 Panel three—Staying Relevant: the Dáil in its second century Chair: tbc Introductory comments by David Farrell, MRIA, School of Politics and International Relations, UCD on ‘Recent changes and innovations in Irish parliamentary processes’ Panellists: Richard Boyd Barrett, TD Lisa Chambers, TD Frances Fitzgerald, TD Aengus Ó Snodaigh, TD Jan O'Sullivan, TD Eamon Ryan, TD 15:30 Tea/Coffee 16:00 Panel four—Public Perceptions of Dáil Éireann: 100 years later Chair: Pat Rabbitte, Former Minister and Labour Party Leader Panellists: Katie Hannon, RTE Current Affairs Alison O’Connor, Irish Examiner Fionnán Sheahan, Irish Independent Mary C. -

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party

James Connolly and the Irish Labour Party Donal Mac Fhearraigh 100 years of celebration? to which White replied, `Put that furthest of all1' . White was joking but only just, 2012 marks the centenary of the founding and if Labour was regarded as conservative of the Irish Labour Party. Like most politi- at home it was it was even more so when cal parties in Ireland, Labour likes to trade compared with her sister parties. on its radical heritage by drawing a link to One historian described it as `the most Connolly. opportunistically conservative party in the On the history section of the Labour known world2.' It was not until the late Party's website it says, 1960s that the party professed an adher- ence to socialism, a word which had been `The Labour Party was completely taboo until that point. Ar- founded in 1912 in Clonmel, guably the least successful social demo- County Tipperary, by James cratic or Labour Party in Western Europe, Connolly, James Larkin and the Irish Labour Party has never held office William O'Brien as the polit- alone and has only been the minority party ical wing of the Irish Trade in coalition. Labour has continued this tra- Union Congress(ITUC). It dition in the current government with Fine is the oldest political party Gael. Far from being `the party of social- in Ireland and the only one ism' it has been the party of austerity. which pre-dates independence. The founders of the Labour The Labour Party got elected a year Party believed that for ordi- ago on promises of burning the bondhold- nary working people to shape ers and defending ordinary people against society they needed a political cutbacks. -

A Diachronic Study of Unparliamentary Language in the New Zealand Parliament, 1890-1950

WITHDRAW AND APOLOGISE: A DIACHRONIC STUDY OF UNPARLIAMENTARY LANGUAGE IN THE NEW ZEALAND PARLIAMENT, 1890-1950 BY RUTH GRAHAM A thesis submitted to the Victoria University of Wellington in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Applied Linguistics Victoria University of Wellington 2016 ii “Parliament, after all, is not a Sunday school; it is a talking-shop; a place of debate”. (Barnard, 1943) iii Abstract This study presents a diachronic analysis of the language ruled to be unparliamentary in the New Zealand Parliament from 1890 to 1950. While unparliamentary language is sometimes referred to as ‘parliamentary insults’ (Ilie, 2001), this study has a wider definition: the language used in a legislative chamber is unparliamentary when it is ruled or signalled by the Speaker as out of order or likely to cause disorder. The user is required to articulate a statement of withdrawal and apology or risk further censure. The analysis uses the Communities of Practice theoretical framework, developed by Wenger (1998) and enhanced with linguistic impoliteness, as defined by Mills (2005) in order to contextualise the use of unparliamentary language within a highly regulated institutional setting. The study identifies and categorises the lexis of unparliamentary language, including a focus on examples that use New Zealand English or te reo Māori. Approximately 2600 examples of unparliamentary language, along with bibliographic, lexical, descriptive and contextual information, were entered into a custom designed relational database. The examples were categorised into three: ‘core concepts’, ‘personal reflections’ and the ‘political environment’, with a number of sub-categories. This revealed a previously unknown category of ‘situation dependent’ unparliamentary language and a creative use of ‘animal reflections’. -

Dáil Éireann

Vol. 1006 Wednesday, No. 7 12 May 2021 DÍOSPÓIREACHTAÍ PARLAIMINTE PARLIAMENTARY DEBATES DÁIL ÉIREANN TUAIRISC OIFIGIÚIL—Neamhcheartaithe (OFFICIAL REPORT—Unrevised) Insert Date Here 12/05/2021A00100Ábhair Shaincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Matters 884 12/05/2021A00175Saincheisteanna Tráthúla - Topical Issue Debate 885 12/05/2021A00200Digital Hubs ����������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������������885 12/05/2021B00350Hospital Waiting Lists 887 12/05/2021C00400Special Educational Needs 891 12/05/2021E00300Harbours and Piers 894 12/05/2021F00600Companies (Protection of Employees’ Rights in Liquidations) Bill 2021: Second Stage [Private Members] 897 12/05/2021S00500Ceisteanna ó Cheannairí - Leaders’ Questions 925 12/05/2021W00500Ceisteanna ar Reachtaíocht a Gealladh - Questions on Promised Legislation 935 12/05/2021AA00800Pensions (Amendment) (Transparency in Charges) Bill 2021: First Stage 945 12/05/2021AA01700Health (Regulation of Termination of Pregnancy) (Foetal Pain Relief) Bill 2021: First Stage 946 12/05/2021BB00900Ministerial Rota for Parliamentary Questions: Motion -

ALAN KELLY TD DELIVERING for the PEOPLE of NENAGH Summer 2015

ALAN KELLY TD DELIVERING FOR THE PEOPLE OF NENAGH Summer 2015 Dear Constituent, I am honoured to serve the people of Nenagh along with Cllr Fiona Bonfield. I am delighted to take this opportunity to update you on some of the local matters that have arisen and show the progress that is being made in all areas for the benefit of the town as a whole. You will find here details of some of the work I have been doing and the funding that I have secured for the local area. As your public representative I am committed to working for all of Tipperary and ensuring that it is treated as a priority by the Government. I am very proud of all that I have delivered for Nenagh to date and that the town has changed for the better over the last four years. It is now very important for me to continue working for the area and my biggest aim is to continue promoting Nenagh as an attractive location for firms to start up or expand and in turn to boost job creation in the town. Please feel free to contact me or Cllr Bonfield at any time. ST. MARY’S MASTERCHEFS Congratulations to Mary’s Masterchefs from St Mary’s Secondary School, Nenagh – Aisling Sheedy, Sorcha Nagle , Jade Corcoran, Roisin Taplin and Niamh Dolan. They were the winners of the Senior Category in the Tipperary Student Enterprise Awards. This book was dedicated to the late Mr Brian McDermott. Brian was a fantastic person. It was always a pleasure to meet him and he was a very kind and funny person. -

New Year Update 2019 Sean Kelly

Update from your MEP for Ireland-South SEÁN KELLY MEP MEMBER OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT Hello and welcome to my New Year’s update MY ROLES after what has been another busy, exciting and > As Leader of Fine Gael in EP I am on the European People’s challenging year as your MEP for Ireland South. Party (EPP) front bench and attend important EPP With this newsletter, I want to update you on some of the Bureau meetings important work that I have been involved in on your behalf > I am a member of the over the past year. The work done at EU level impacts us Parliament’s Committees on all on a daily basis and with Brexit on the horizon, it is more Industry, Research and Energy important now than ever that we have strong and influential (ITRE), International Trade Irish representation in Brussels. As Leader of Fine Gael in (INTA), Fisheries (PECH) and the European Parliament, and senior EPP Group MEP, I work Pesticides (PEST) hard daily to ensure this is the case. I hope you enjoy this > I sit on the Delegations for newsletter and find it useful, and I wish you all a happy and relations with Iran, the United prosperous 2019! States, and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) 5 KEY ACHIEVEMENTS IN 2018 Worked closely with Delivered the 32% As EPP lead negotiator on 1 Brexit negotiator 2 Renewable Energy target 4 South-East Asia, oversaw Michel Barnier and EPP leader for 2030 following tough the signing of the new EU- Manfred Weber negotiations with the EU Council Singapore Free Trade Agreement to help maintain unwavering 3 Appointed ITRE 5 After a long campaign, EU support for Committee rapporteur finally ensured European Irish position on for €650 billion InvestEU Commission action to end the border programme and secured backing biannual clock change for my proposals www.seankelly.eu RENEWABLE 32% of our energy in ENERGY Europe will This past year brought one of the proudest be renewable achievements of my political career. -

Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians

Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Background Study: Professional and Ethical Standards for Parliamentarians Warsaw, 2012 Published by the OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR) Ul. Miodowa 10, 00–251 Warsaw, Poland http://www.osce.org/odihr © OSCE/ODIHR 2012, ISBN 978–92–9234–844–1 All rights reserved. The contents of this publication may be freely used and copied for educational and other non-commercial purposes, provided that any such reproduction is accompanied by an acknowledgement of the OSCE/ODIHR as the source. Designed by Homework Cover photo of the Hungarian Parliament Building by www.heatheronhertravels.com. Printed by AGENCJA KARO Table of contents Foreword 5 Executive Summary 8 Part One: Preparing to Reform Parliamentary Ethical Standards 13 1.1 Reasons to Regulate Conduct 13 1.2 The Limits of Regulation: Private Life 19 1.3 Immunity for Parliamentarians 20 1.4 The Context for Reform 25 Part Two: Tools for Reforming Ethical Standards 31 2.1 A Code of Conduct 34 2.2 Drafting a Code 38 2.3 Assets and Interests 43 2.4 Allowances, Expenses and Parliamentary Resources 49 2.5 Relations with Lobbyists 51 2.6 Other Areas that may Require Regulation 53 Part Three: Monitoring and Enforcement 60 3.1 Making a Complaint 62 3.2 Investigating Complaints 62 3.3 Penalties for Misconduct 69 3.4 Administrative Costs 71 3.5 Encouraging Compliance 72 3.6 Updating and Reviewing Standards 75 Conclusions 76 Glossary 79 Select Bibliography 81 Foreword The public accountability and political credibility of Parliaments are cornerstone principles, to which all OSCE participating States have subscribed.