Integrating Humanoid Body, Emotions, and Time Perception to Investigate Social Interaction and Human Cognition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Current Advances in Cognitive Robotics Amir Aly, Sascha Griffiths, Francesca Stramandinoli

Towards Intelligent Social Robots: Current Advances in Cognitive Robotics Amir Aly, Sascha Griffiths, Francesca Stramandinoli To cite this version: Amir Aly, Sascha Griffiths, Francesca Stramandinoli. Towards Intelligent Social Robots: Current Advances in Cognitive Robotics . France. 2015. hal-01673866 HAL Id: hal-01673866 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01673866 Submitted on 1 Jan 2018 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Proceedings of the Full Day Workshop Towards Intelligent Social Robots: Current Advances in Cognitive Robotics in Conjunction with Humanoids 2015 South Korea November 3, 2015 Amir Aly1, Sascha Griffiths2, Francesca Stramandinoli3 1- ENSTA ParisTech – France 2- Queen Mary University – England 3- Italian Institute of Technology – Italy Towards Emerging Multimodal Cognitive Representations from Neural Self-Organization German I. Parisi, Cornelius Weber and Stefan Wermter Knowledge Technology Institute, Department of Informatics University of Hamburg, Germany fparisi,weber,[email protected] http://www.informatik.uni-hamburg.de/WTM/ Abstract—The integration of multisensory information plays a processing of a huge amount of visual information to learn crucial role in autonomous robotics. In this work, we investigate inherent spatiotemporal dependencies in the data. To tackle how robust multimodal representations can naturally develop in this issue, learning-based mechanisms have been typically used a self-organized manner from co-occurring multisensory inputs. -

Robotic Pets in Human Lives: Implications for the Human–Animal Bond and for Human Relationships with Personified Technologies ∗ Gail F

Journal of Social Issues, Vol. 65, No. 3, 2009, pp. 545--567 Robotic Pets in Human Lives: Implications for the Human–Animal Bond and for Human Relationships with Personified Technologies ∗ Gail F. Melson Purdue University Peter H. Kahn, Jr. University of Washington Alan Beck Purdue University Batya Friedman University of Washington Robotic “pets” are being marketed as social companions and are used in the emerging field of robot-assisted activities, including robot-assisted therapy (RAA). However,the limits to and potential of robotic analogues of living animals as social and therapeutic partners remain unclear. Do children and adults view robotic pets as “animal-like,” “machine-like,” or some combination of both? How do social behaviors differ toward a robotic versus living dog? To address these issues, we synthesized data from three studies of the robotic dog AIBO: (1) a content analysis of 6,438 Internet postings by 182 adult AIBO owners; (2) observations ∗ Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Gail F. Melson, Depart- ment of CDFS, 101 Gates Road, Purdue University, West Lafayette, IN 47907-20202 [e-mail: [email protected]]. We thank Brian Gill for assistance with statistical analyses. We also thank the following individuals (in alphabetical order) for assistance with data collection, transcript preparation, and coding: Jocelyne Albert, Nathan Freier, Erik Garrett, Oana Georgescu, Brian Gilbert, Jennifer Hagman, Migume Inoue, and Trace Roberts. This material is based on work supported by the National Science Foundation under Grant No. IIS-0102558 and IIS-0325035. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation. -

Lower Body Design of the `Icub' a Human-Baby Like Crawling Robot

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by University of Salford Institutional Repository Lower Body Design of the ‘iCub’ a Human-baby like Crawling Robot N.G.Tsagarakis M. Sinclair F. Becchi Center of Robotics and Automation Center of Robotics and Automation TELEROBOT University of Salford University of Salford Advanced Robotics Salford , M5 4WT, UK Salford , M5 4WT, UK 16128 Genova, Italy [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] G. Metta G. Sandini D.G.Caldwell LIRA-Lab, DIST LIRA-Lab, DIST Center of Robotics and Automation University of Genova University of Genova University of Salford 16145 Genova, Italy 16145 Genova, Italy Salford , M5 4WT, UK [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Abstract – The development of robotic cognition and a human like robots has led to the development of H6 and H7 greater understanding of human cognition form two of the [2]. Within the commercial arena there were also robots of current greatest challenges of science. Within the considerable distinction including those developed by RobotCub project the goal is the development of an HONDA. Their second prototype, P2, was introduced in 1996 embodied robotic child (iCub) with the physical and and provided an important step forward in the development of ultimately cognitive abilities of a 2 ½ year old human full body humanoid systems [3]. P3 introduced in 1997 was a baby. The ultimate goal of this project is to provide the scaled down version of P2 [4]. ASIMO (Advanced Step in cognition research community with an open human like Innovative Mobility) a child sized robot appeared in 2000. -

Fun Facts and Activities

Robo Info: Fun Facts and Activities By: J. Jill Rogers & M. Anthony Lewis, PhD Robo Info: Robot Activities and Fun Facts By: J. Jill Rogers & M. Anthony Lewis, PhD. Dedication To those young people who dare to dream about the all possibilities that our future holds. Special Thanks to: Lauren Buttran and Jason Coon for naming this book Ms. Patti Murphy’s and Ms. Debra Landsaw’s 6th grade classes for providing feedback Liudmila Yafremava for her advice and expertise i Iguana Robotics, Inc. PO Box 625 Urbana, IL 61803-0625 www.iguana-robotics.com Copyright 2004 J. Jill Rogers Acknowledgments This book was funded by a research Experience for Teachers (RET) grant from the National Science Foundation. Technical expertise was provided by the research scientists at Iguana Robotics, Inc. Urbana, Illinois. This book’s intended use is strictly for educational purposes. The author would like to thank the following for the use of images. Every care has been taken to trace copyright holders. However, if there have been unintentional omissions or failure to trace copyright holders, we apologize and will, if informed, endeavor to make corrections in future editions. Key: b= bottom m=middle t=top *=new page Photographs: Cover-Iguana Robotics, Inc. technical drawings 2003 t&m; http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html b* i- Iguana Robotics, Inc. technical drawings 2003m* p1- http://www.history.rochester.edu/steam/hero/ *p2- Encyclopedia Mythica t *p3- Museum of Art Neuchatel t* p5- (c) 1999-2001 EagleRidge Technologies, Inc. b* p9- Copyright 1999 Renato M.E. Sabbatini http://www.epub.org.br/cm/n09/historia/greywalter_i.htm t ; http://www.ar2.com/ar2pages/uni1961.htm *p10- http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html /*p11- http://robot.kaist.ac.kr/~songsk/robot/robot.html; Sojourner, http://marsrovers.jpl.nasa.gov/home/ *p12- Sony Aibo, The Sony Corporation of America, 550 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10022 t; Honda Asimo, Copyright, 2003 Honda Motor Co., Ltd. -

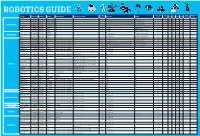

Robotics Section Guide for Web.Indd

ROBOTICS GUIDE Soldering Teachers Notes Early Higher Hobby/Home The Robot Product Code Description The Brand Assembly Required Tools That May Be Helpful Devices Req Software KS1 KS2 KS3 KS4 Required Available Years Education School VEX 123! 70-6250 CLICK HERE VEX No ✘ None No ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dot 70-1101 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Dash 70-1100 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ready to Go Robot Cue 70-1108 CLICK HERE Wonder Workshop No ✘ iOS or Android phones/tablets. Apps are also available for Kindle. Free Apps to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Codey Rocky 75-0516 CLICK HERE Makeblock No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloadb ale Mblock Software ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ozobot 70-8200 CLICK HERE Ozobot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Ohbot 76-0000 CLICK HERE Ohbot No ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ SoftBank NAO 70-8893 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Humanoid Robots SoftBank Pepper 70-8870 CLICK HERE No ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Choregraph - free to download ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ Robotics Ohbot 76-0001 CLICK HERE Ohbot Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop Free downloads for Windows or Pi ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ FABLE 00-0408 CLICK HERE Shape Robotics Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ PC, Laptop or Ipad Free Downloadable ✔ ✔ ✔ ✔ VEX GO! 70-6311 CLICK HERE VEX Assembly is part of the fun & learning! ✘ Windows, Mac, -

Martine Rothblatt

For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] Martine Rothblatt Topics Activism and Social Justice, Diversity and Inclusion, Health and Wellness, LGBTQIA+, Lifestyle, Science and Technology Travels From Maryland Bio Martine Rothblatt, Ph.D., MBA, J.D. is one of the most exciting and innovative voices in the world of business, technology, and medicine. She was named by Forbes as one of the "100 Greatest Living Business Minds of the past 100 years" and one of America's Self-Made Women of 2019. After graduating from UCLA with a law and MBA degree, Martine served as President & CEO of Dr. Gerard K. O’Neill’s satellite navigation company, Geostar. The satellite system she launched in 1986 continues to operate today, providing service to certain government agencies. She also created Sirius Satellite Radio in 1990, serving as its Chairman and CEO. In the years that followed, Martine Rothblatt’s daughter was diagnosed with life-threatening pulmonary hypertension. Determined to find a cure, she left the communications business and entered the world of medical biotechnology. She earned her Ph.D. in medical ethics at the Royal London College of Medicine & Dentistry and founded the United Therapeutics Corporation in 1996. The company focuses on the development and commercialization of page 1 / 4 For more information contact us on: North America 855.414.1034 International +1 646.307.5567 [email protected] biotechnology in order to address the unmet medical needs of patients with chronic and life-threatening conditions. Since then, she has become the highest-paid female CEO in America. -

AI, Robots, and Swarms: Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies

AI, Robots, and Swarms Issues, Questions, and Recommended Studies Andrew Ilachinski January 2017 Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. This document contains the best opinion of CNA at the time of issue. It does not necessarily represent the opinion of the sponsor. Distribution Approved for Public Release; Distribution Unlimited. Specific authority: N00014-11-D-0323. Copies of this document can be obtained through the Defense Technical Information Center at www.dtic.mil or contact CNA Document Control and Distribution Section at 703-824-2123. Photography Credits: http://www.darpa.mil/DDM_Gallery/Small_Gremlins_Web.jpg; http://4810-presscdn-0-38.pagely.netdna-cdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/ Robotics.jpg; http://i.kinja-img.com/gawker-edia/image/upload/18kxb5jw3e01ujpg.jpg Approved by: January 2017 Dr. David A. Broyles Special Activities and Innovation Operations Evaluation Group Copyright © 2017 CNA Abstract The military is on the cusp of a major technological revolution, in which warfare is conducted by unmanned and increasingly autonomous weapon systems. However, unlike the last “sea change,” during the Cold War, when advanced technologies were developed primarily by the Department of Defense (DoD), the key technology enablers today are being developed mostly in the commercial world. This study looks at the state-of-the-art of AI, machine-learning, and robot technologies, and their potential future military implications for autonomous (and semi-autonomous) weapon systems. While no one can predict how AI will evolve or predict its impact on the development of military autonomous systems, it is possible to anticipate many of the conceptual, technical, and operational challenges that DoD will face as it increasingly turns to AI-based technologies. -

The Last of the Dinosaurs

020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 1 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 2 This book is your passport into time. Can you survive in the Age of Dinosaurs? Turn the page to find out. 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 3 The Last of the Dinosaurs by Peter Lerangis illustrated by Doug Henderson A Byron Preiss Book 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 4 To Peter G. Hayes, for his friendship, interest, and help Copyright @ 1988, 2001 by Byron Preiss Visual Publications “Time Machine” is a registered trademark of Byron Preiss Visual Publications, Inc. Registered in the U.S. Patent and Trademark office. Cover painting by Mark Hallett Cover design by Alex Jay An ipicturebooks.com ebook ipicturebooks.com 24 West 25th St., 11th fl. NY, NY 10010 The ipicturebooks World Wide Web Site Address is: http://www.ipicturebooks.com Original ISBN: 0-553-27007-9 eISBN: 1-59019-087-4 This Text Converted to eBook Format for the Microsoft® Reader. 020063_TimeMachine22.qxd 8/7/01 3:26 PM Page 5 ATTENTION TIME TRAVELER! This book is your time machine. Do not read it through from beginning to end. In a moment you will receive a mission, a special task that will take you to another time period. As you face the dan- gers of history, the Time Machine often will give you options of where to go or what to do. This book also contains a Data Bank to tell you about the age you are going to visit. -

From Human-Computer Interaction to Human-Robot Social Interaction

From Human-Computer Interaction to Human-Robot Social Interaction Tarek Toumi and Abdelmadjid Zidani LaSTIC Laboratory, Computer Science Department University of Batna, 05000 Algeria Abstract also called OCC model. Those models are based on Human-Robot Social Interaction became one of active research theories of evaluations that allow specifying properties of fields in which researchers from different areas propose solutions critical events that can cause particular emotions [6], [7], and directives leading robots to improve their interactions with [8]. humans. In this paper we propose to introduce works in both human robot interaction and human computer interaction and to Concerning Works in robotics Bartneck [9] proposed a make a bridge between them, i.e. to integrate emotions and capabilities concepts of the robot in human computer model to definition and design guidelines of social robots. Several become adequate for human robot interaction and discuss architectures and theories have been proposed [5], [4], and challenges related to the proposed model. Finally an illustration some of them have been used in the design step. Many through real case of this model will be presented. others works could be find in [1], [2], [3]. Keywords: Human-Computer Interaction, Human-robot social In which concern the works in human computer interaction, social robot. interaction, Norman [10] by his action theory, describes how humans doing their actions by modeling cognitive steps used in accomplishment a task. Jean Scholtz [11] 1. Introduction used Norman’s action theory and described an evaluation methodology based on situational awareness. Building robots that can interact socially and in a robust way with humans is the main goal of Human-robot social From typical models used in human computer interaction, interaction researchers, a survey of previous works could this paper proposes some modifications to be used in be found in [1], [2], [3]. -

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: a Humanoid Robot with Human-Like Proportions

Cybernetic Human HRP-4C: A humanoid robot with human-like proportions Shuuji KAJITA, Kenji KANEKO, Fumio KANEIRO, Kensuke HARADA, Mitsuharu MORISAWA, Shin’ichiro NAKAOKA, Kanako MIURA, Kiyoshi FUJIWARA, Ee Sian NEO, Isao HARA, Kazuhito YOKOI, Hirohisa HIRUKAWA Abstract Cybernetic human HRP-4C is a humanoid robot whose body dimensions were designed to match the average Japanese young female. In this paper, we ex- plain the aim of the development, realization of human-like shape and dimensions, research to realize human-like motion and interactions using speech recognition. 1 Introduction Cybernetics studies the dynamics of information as a common principle of com- plex systems which have goals or purposes. The systems can be machines, animals or a social systems, therefore, cybernetics is multidiciplinary from its nature. Since Norbert Wiener advocated the concept in his book in 1948[1], the term has widely spreaded into academic and pop culture. At present, cybernetics has diverged into robotics, control theory, artificial intelligence and many other research fields, how- ever, the original unified concept has not yet lost its glory. Robotics is one of the biggest streams that branched out from cybernetics, and its goal is to create a useful system by combining mechanical devices with information technology. From a practical point of view, a robot does not have to be humanoid; nevertheless we believe the concept of cybernetics can justify the research of hu- manoid robots for it can be an effective hub of multidiciplinary research. WABOT-1, -

Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile

FETISHISM AND THE CULTURE OF THE AUTOMOBILE James Duncan Mackintosh B.A.(hons.), Simon Fraser University, 1985 THESIS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of Communication Q~amesMackintosh 1990 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY August 1990 All rights reserved. This work may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by photocopy or other means, without permission of the author. APPROVAL NAME : James Duncan Mackintosh DEGREE : Master of Arts (Communication) TITLE OF THESIS: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile EXAMINING COMMITTEE: Chairman : Dr. William D. Richards, Jr. \ -1 Dr. Martih Labbu Associate Professor Senior Supervisor Dr. Alison C.M. Beale Assistant Professor \I I Dr. - Jerry Zqlove, Associate Professor, Department of ~n~lish, External Examiner DATE APPROVED : 20 August 1990 PARTIAL COPYRIGHT LICENCE I hereby grant to Simon Fraser University the right to lend my thesis or dissertation (the title of which is shown below) to users of the Simon Fraser University Library, and to make partial or single copies only for such users or in response to a request from the library of any other university, or other educational institution, on its own behalf or for one of its users. I further agree that permission for multiple copying of this thesis for scholarly purposes may be granted by me or the Dean of Graduate Studies. It is understood that copying or publication of this thesis for financial gain shall not be allowed without my written permission. Title of Thesis/Dissertation: Fetishism and the Culture of the Automobile. Author : -re James Duncan Mackintosh name 20 August 1990 date ABSTRACT This thesis explores the notion of fetishism as an appropriate instrument of cultural criticism to investigate the rites and rituals surrounding the automobile. -

Exploring the Social, Moral, and Temporal Qualities of Pre-Service

Exploring the Social, Moral, and Temporal Qualities of Pre-Service Teachers’ Narratives of Evolution Deirdre Hahn Division of Psychology in Education, College of Education, Arizona State University, PO Box 878409, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] Sarah K Brem Division of Psychology in Education, College of Education, Arizona State University, PO Box 870611, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] Steven Semken Department of Geological Sciences, Arizona State University, PO Box 871404, Tempe, Arizona 85287 [email protected] ABSTRACT consequences of accepting evolutionary theory. That is, both evolutionists and creationists tend to believe that Elementary, middle, and secondary school teachers may accepting evolutionary theory will result in a greater experience considerable unease when teaching evolution ability to justify or engage in racist or selfish behavior, in the context of the Earth or life sciences (Griffith and and will reduce people's sense of purpose and Brem, in press). Many factors may contribute to their self-determination. Further, Griffith and Brem (in press) discomfort, including personal conceptualizations of the found that in-service science teachers frequently share evolutionary process - especially human evolution, the these same beliefs and to avoid controversy in the most controversial aspect of evolutionary theory. classroom, the teachers created their own boundaries in Knowing more about the mental representations of an curriculum and teaching practices. evolutionary process could help researchers to There is a historical precedent for uneasiness around understand the challenges educators face in addressing evolutionary theory, particularly given its use to explain scientific principles. These insights could inform and justify actions performed in the name of science.