Harrowing Journeys

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Democracy Not for Sale: the Struggle for Food Sovereignty in the Age of Austerity in Greece | 3 Glossary

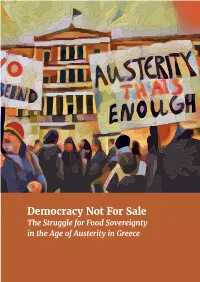

Democracy Not For Sale The Struggle for Food Sovereignty in the Age of Austerity in Greece o AUTHORS: (in alphabetical order) Stephan Backes, Jenny Gkiougki, Sylvia Kay, Charalampos Konstantinidis, Emily Mattheisen, Christina Sakali, Eirini-Erifyli Tzekou, Leonidas Vatikiotis, Pietje Vervest. COPYEDITOR: Deborah Eade DESIGN: Brigitte Vos www.vosviscom.nl PRINT: Jubels Amsterdam, Heidelberg, Athens/Thessaloniki, November, 2018. Published by Transnational Institute, FIAN International and Agroecopolis. ABOUT THE RESEARCH COLLECTIVE: This report is the result of a collective research process undertaken by the abovementioned authors between October 2017 and September 2018. The research relies on original fieldwork and interviews with persons throughout Greece, macro-economic statistical analysis, and literature reviews of key texts. For a more detailed description of our research locations and persons interviewed, refer to the methodological note in the Annex. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The authors wish to thank the following persons (in alphabetical order) for their contributions to the production of this report: Ilias Bantekas, Felipe Bley-Folly, Nick Buxton, Christos Giovanopoulos, Raphaël Gonçalves Alves, Rolf Künnemann, Andrea Nuila, Emma Luce Scali, Yifang Slot-Tang, Ana Maria Suárez Franco, Yiorgos Vassalos, Renaud Vivien. Table of Contents Glossary 4 Executive summary 5 Foreword 11 Introduction 19 Chapter 1. Austerity and the agri-food system 24 1.1 The Greek agri-food system from 1981 to 2010 24 1.1 (a) Undermining food sovereignty: the role -

Ηεllenic Ministry of Labour Social Security And

ΗΕLLENIC MINISTRY OF LABOUR SOCIAL SECURITY AND SOCIAL SOLIDARITY 1. CLOSE CARE i. 12 Social Welfare Centers [Law n. 4109/2013, (GG 16, A, 23.01.2013)], as well as the Papafio Center for Male Children Welfare of Thessaloniki (Law n 4199/2013, GG 216, A, 11.10.2013) The problems of child protection are addressed through the Child Protection Departments, the 12 Social Welfare Centers established by Article 9 (1) of Law n. 4109/2013 (GG 16, A, 23.01.2013) and the Papafio Center for Male Child Welfare of Thessaloniki established by the Law n. 4199/2013 (GG 216, A, 11.10.2013). These Centers function under the auspices of the Ministry of Labor, Social Security and Social Solidarity, are based principally on the respective Region and their purpose has been broadened so that they can now intervene in matters of family protection, childhood, youth, elderly, people with disabilities and vulnerable groups of the population. The Child Protection Departments of the above-mentioned Centers aim to provide care, psycho-social development and, in general, care for the education and employment of children who are proven to be unprotected and lacking family care until their adaptation to an environment that guarantees their best development (foster care families or adoption). Also, in the above-mentioned Centers are provided services of treatment and rehabilitation (psycho-social support, physiotherapy, speech therapy, occupational therapy, nursing care) by the relevant scientific and specialized personnel (psychologists, social workers, carers, etc.) through programs for children and adults. In addition, through open-care programs, services are provide in order to diagnose and evaluate of problems, give opinions and treatment to children with physical, mental- cognitive and psycho-emotional disorders, speech and communication disorders, learning difficulties, dyslexia, difficulties in attention and concentration and/or behavioral problems. -

EUR/RC68/5 Rev.1: Leaving No One Behind

Regional Committee for Europe EUR/RC68/5 Rev.1 68th session + EUR/RC68/Conf.Doc./1 Rev.1 Rome, Italy, 17–20 September 2018 31 August 2018 180470 Provisional agenda item 2(a) ORIGINAL: ENGLISH Leaving no one behind: report of the Regional Director on the work of WHO in the European Region in 2016–2017 This report highlights some of the most important work of the WHO Regional Office for Europe in 2016–2017 for better health in the WHO European Region. In 2016–2017, the WHO Regional Office for Europe responded to current political and social challenges, while carrying out its activities within the new global framework of the United Nations 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. This required the Regional Office to continue and intensify the approach and strategic directions it had pursued since 2010, when the WHO European Region adopted the WHO Regional Director for Europe’s new vision for health in response to changing circumstances and new challenges, and 2012, when it adopted Health 2020. WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE FOR EUROPE UN City, Marmorvej 51, DK-2100 Copenhagen Ø, Denmark Telephone: +45 45 33 70 00 Fax: +45 45 33 70 01 Email: [email protected] Web: http://www.euro.who.int/en/who-we-are/governance EUR/RC68/5 Rev.1 page 2 Contents Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................. 4 1. Better health for Europe: more equitable and sustainable ...................................................... 6 Introduction ......................................................................................................................