Using Epidata & Epi Info for Windows

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patient Safety Culture and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia: an Institutional Based Cross-Sectional Study

Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety Dovepress open access to scientific and medical research Open Access Full Text Article ORIGINAL RESEARCH Patient Safety Culture and Associated Factors Among Health Care Providers in Bale Zone Hospitals, Southeast Ethiopia: An Institutional Based Cross-Sectional Study This article was published in the following Dove Press journal: Drug, Healthcare and Patient Safety Musa Kumbi1 Introduction: Patient safety is a serious global public health issue and a critical component of Abduljewad Hussen 1 health care quality. Unsafe patient care is associated with significant morbidity and mortality Abate Lette1 throughout the world. In Ethiopia health system delivery, there is little practical evidence of Shemsu Nuriye2 patient safety culture and associated factors. Therefore, this study aims to assess patient safety Geroma Morka3 culture and associated factors among health care providers in Bale Zone hospitals. Methods: A facility-based cross-sectional study was undertaken using the “Hospital Survey 1 Department of Public Health, Goba on Patient Safety Culture (HSOPSC)” questionnaire. A total of 518 health care providers Referral Hospital, Madda Walabu University, Goba, Ethiopia; 2Department were interviewed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was employed to examine statistical of Public Health, College of Health differences between hospitals and patient safety culture dimensions. We also computed Science and Medicine, Wolayta Sodo internal consistency coefficients and exploratory factor analysis. Bivariate and multivariate University, Sodo, Ethiopia; 3Department of Nursing, Goba Referral Hospital, linear regression analyses were performed using SPSS version 20. The level of significance Madda Walabu University, Goba, Ethiopia was established using 95% confidence intervals and a p-value of <0.05. Results: The overall level of patient safety culture was 44% (95% CI: 43.3–44.6) with a response rate of 93.2%. -

Association Between Indoor Air Pollution and Cognitive Impairment Among Adults in Rural Puducherry, South India Yuvaraj Krishnamoorthy, Gokul Sarveswaran, K

Published online: 2019-09-02 Original Article Association between Indoor Air Pollution and Cognitive Impairment among Adults in Rural Puducherry, South India Yuvaraj Krishnamoorthy, Gokul Sarveswaran, K. Sivaranjini, Manikandanesan Sakthivel, Marie Gilbert Majella, S. Ganesh Kumar Department of Preventive and Background: Recent evidences showed that outdoor air pollution had significant Social Medicine, Jawaharlal influence on cognitive functioning of adults. However, little is known regarding the Institute of Postgraduate Medical Education and association of indoor air pollution with cognitive dysfunction. Hence, the current study was done to assess the association between indoor air pollution and cognitive Research, Puducherry, India Abstract impairment among adults in rural Puducherry. Methodology: A community‑based cross‑sectional study was done among 295 adults residing in rural field practice area of tertiary care institute in Puducherry during February and March 2018. Information regarding sociodemographic profile and household was collected using pretested semi‑structured questionnaire. Mini‑Mental State Examination was done to assess cognitive function. We calculated adjusted prevalence ratios (aPR) to identify the factors associated with cognitive impairment. Results: Among 295 participants, 173 (58.6) were in 30–59 years; 154 (52.2%) were female; and 59 (20.0%) were exposed to indoor air pollution. Prevalence of cognitive impairment in the general population was 11.9% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 8.7–16.1). Prevalence of cognitive impairment among those who were exposed to indoor air pollution was 27.1% (95% CI: 17.4–39.6). Individuals exposed to indoor air pollution (aPR = 2.18, P = 0.003) were found to have two times more chance of having cognitive impairment. -

Eric Brenner, MD – Brief Biosketch: (Update of December 2018) *** Email Contact: [email protected]

Eric Brenner, MD – Brief Biosketch: (Update of December 2018) *** Email contact: [email protected] Eric Brenner is a medical epidemiologist and public health physician who currently resides in Columbia, South Carolina (USA). He attended the University of California at Berkeley where he majored in French Literature. After graduation he joined the Peace Corps and worked as a secondary school teacher in the Ivory Coast (West Africa) for two years. He then attended Dartmouth Medical School and completed subsequent clinical training both in San Francisco and in South Carolina (SC) which led to Board Certification in Internal Medicine and Infectious Disease. He has over 35 years experience with communicable disease control programs having worked at different times at the state level with the SC Department of Health and Environmental Control (SC-DHEC), at the national level with the US Centers for Disease Control (CDC), and internationally with the World Health Organization (WHO) where he worked for a year in Geneva with the Expanded Programme on Immunization (EPI) as well as on short- term assignments in a number of other countries. He has also worked as a consultant with other international agencies including UNICEF, PAHO and USAID. In 2015 he worked for six weeks with a CDC team in the Ivory Coast focusing on that W. African country’s preparedness for possible introduction of Ebola Virus Disease (EVD), and in 2018, again as a CDC consultant, worked for a month in Guinea on a project to help that country strengthen its Integrated Disease -

Antiretroviral Adverse Drug Reactions Pharmacovigilance in Harare City

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/358069; this version posted June 28, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 1 Original Manuscript 2 Title: Antiretroviral Adverse Drug Reactions Pharmacovigilance in Harare City, 3 Zimbabwe, 2017 4 Hamufare Mugauri1, Owen Mugurungi2, Tsitsi Juru1, Notion Gombe1, Gerald 5 Shambira1 ,Mufuta Tshimanga1 6 7 1. Department of Community Medicine, University of Zimbabwe 8 2. Ministry of Health and Child Care, Zimbabwe 9 10 Corresponding author: 11 Tsitsi Juru [email protected] 12 Office 3-66 Kaguvi Building, Cnr 4th/Central Avenue 13 University of Zimbabwe, Harare, Zimbabwe 14 Phone: +263 4 792157, Mobile: +263 772 647 465 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/358069; this version posted June 28, 2018. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. 15 Abstract 16 Introduction: Key to pharmacovigilance is spontaneously reporting all Adverse Drug 17 Reactions (ADR) during post-market surveillance. This facilitates identification and 18 evaluation of previously unreported ADR’s, acknowledging the trade-off between 19 benefits and potential harm of medications. Only 41% ADR’s documented in Harare 20 city clinical records for January to December 2016 were reported to Medicines 21 Control Authority of Zimbabwe (MCAZ). -

Communicable Disease Control in Emergencies: a Field Manual Edited by M

Communicable disease control in emergencies A field manual Communicable disease control in emergencies A field manual Edited by M.A. Connolly WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Communicable disease control in emergencies: a field manual edited by M. A. Connolly. 1.Communicable disease control–methods 2.Emergencies 3.Disease outbreaks–prevention and control 4.Manuals I.Connolly, Máire A. ISBN 92 4 154616 6 (NLM Classification: WA 110) WHO/CDS/2005.27 © World Health Organization, 2005 All rights reserved. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the pert of the World Health Organization concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted lines on map represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. All reasonable precautions have been taken by WHO to verify he information contained in this publication. However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either express or implied. The responsibility for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages arising in its use. -

CDC CSELS Division of Public Health

Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS) Division of Public Health Information Dissemination (DPHID) The primary mission for the Center for Surveillance, Epidemiology and Laboratory Services (CSELS) is to provide scientific service, expertise, skills, and tools in support of CDC's national efforts to promote health; prevent disease, injury and disability; and prepare for emerging health threats. CSELS has four divisions which represent the tactical arm of CSELS, executing upon CSELS strategic objectives. They are critical to CSELS ability to deliver public health value to CDC in areas such as science, public health practice, education, and data. The four Divisions are: Division of Health Informatics and Surveillance Division of Laboratory Systems Division of Public Health Information Dissemination Division of Scientific Education and Professional Development Applied Public Health Advanced Laboratory Epidemiology The mission of the Division of Public Health Information Dissemination (DPHID) is to serve as a hub for scientific publications, information and library sciences, systematic reviews and recommendations, and public health genomics, thereby collaborating with CDC CIOs and the public health community in producing, disseminating, and implementing evidence-based and actionable information to strengthen public health science and improve public health decision- making. Major Products or Services provided by DEALS include: The American Hospital Association (AHA): AHA Annual Survey and AHA Healthcare IT Survey Data. Contact [email protected] Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) health data coordination - The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Virtual Research Data Center (VRDC) is CDC’s Gateway to CMS Data. CMS has developed a new data access model as an option for requesting Medicare and Medicaid data for a broad range of analytic studies. -

Exposure and Body Burden of Environmental Pollution and Risk Of

Ingela Helmfrid Ingela Linköping University medical dissertations, No. 1699 Exposure and body burden of environmental pollutants and risk of cancer in historically contaminated areas Ingela Helmfrid Exposure and body burden of FACULTY OF MEDICINE AND HEALTH SCIENCES environmental pollutants and risk Linköping University medical dissertations, No. 1699, 2019 of cancer in historically Occupational and Environmental Medicine Center and Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine contaminated areas Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden www.liu.se 2019 Linköping University Medical Dissertation No. 1699 Exposure and body burden of environmental pollutants and risk of cancer in historically contaminated areas Ingela Helmfrid Occupational and Environmental Medicine Center, and Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine Linköpings universitet, SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Linköping 2019 © Ingela Helmfrid, 2019 Printed in Sweden by LiU-Tryck, Linköping University, 2019 Linköping University medical dissertations, No. 1699 ISSN 0345-0082 ISBN 978-91-7685-006-0 Exposure and body burden of environmental pollutants and risk of cancer in historically contaminated areas By Ingela Helmfrid November 2019 ISBN 978-91-7685-006-0 Linköping University medical dissertations, No. 1699 ISSN 0345-0082 Keywords: Contaminated area, cancer, exposure, metals, POPs, Consumption of local food Occupational and Environmental Medicine Center, and Department of Clinical and Experimental Medicine Linköping University SE-581 83 Linköping, Sweden Preface This thesis is transdisciplinary, integrating toxicology, epidemiology and risk assessment, and involving academic institutions as well as national, regional and local authorities. Systematic and transparent methods for the characterization of human environmental exposure to site-specific pollutants in populations living in historically contaminated areas were used. -

The First Line in the Above Code Defines a New Variable Called “Anemic”; the Second Line Assigns Everyone a Value of (-) Or No Meaning They Are Not Anemic

The first line in the above code Defines a new variable called “anemic”; the second line assigns everyone a value of (-) or No meaning they are not anemic. The first and second If commands recodes the “anemic” variable to (+) or Yes if they meet the specified criteria for hemoglobin level and sex. A Note to Epi Info DOS users: Using the DOS version of Epi you had to be very careful about using the Recode and If/Then commands to avoid recoding a missing value in the original variable to a code in the new variable. In the Windows version, if the original value is missing, then the new variable will also usually be missing, but always verify this. Always Verify Coding It is recommended that you List the original variable(s) and newly defined variables to make sure the coding worked as you expected. You can also use the Tables and Means command for double-checking the accuracy of the new coding. Use of Else … The Else part of the If command is usually used for categorizing into two groups. An example of the code is below which separates the individuals in the viewEvansCounty data into “younger” and “older” age categories: DEFINE agegroup3 IF AGE<50 THEN agegroup3="Younger" ELSE agegroup3="Older" END Use of Parentheses ( ) For the Assign and If/Then/Else commands, for multiple mathematical signs, you may need to use parentheses. In a command, the order of mathematical operations performed is as follows: Exponentiation (“^”), multiplication (“*”), division (“/”), addition (“+”), and subtraction (“-“). For example, the following command ASSIGNs a value to a new variable called calc_age based on an original variable AGE (in years): ASSIGN calc_age = AGE * 10 / 2 + 20 For example, a 14 year old would have the following calculation: 14 * 10 / 2 + 20 = 90 First, the multiplication is performed (14 * 10 = 140), followed by the division (140 / 2 = 70), and then the addition (70 + 20 = 90). -

The One Health Approach in Public Health Surveillance and Disease Outbreak Response: Precepts & Collaborations from Sub Saharan Africa

The One Health Approach in Public Health Surveillance and Disease Outbreak Response: Precepts & Collaborations from Sub Saharan Africa Chima J. Ohuabunwo MD, MPH, FWACP Medical Epidemiologist/Assoc. Prof, MSM Department of Medicine & Adjunct Professor, Hubert’s Department of Global Health, Rollins School of Public Health, Emory University, Atlanta GA Learning Objectives: At end of the lecture, participants will be able to; •Define the One Health (OH) concept & approach • State the rationale and priorities of OH Approach • List key historical OH milestones & personalities •Mention core OH principles and stakeholders •Outline some OH precepts & collaborations • Illustrate OH application in public health surveillance and outbreak response 2 Presentation Outline • Definition of the One Health (OH) Concept & Approach • Rationale and Priorities of OH Approach •OH Historical Perspectives •OH approach in Public Health Surveillance & Outbreak Response •One Health Precepts & Collaborations in Africa –West Africa OH Technical Report Recommendations • Conclusion and Next Steps 3 One Health Concept: The What? •The collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines, working locally, nationally and globally, to attain optimal health for people, animals and the environment (AVMA, 2008) •A global strategy for expanding interdisciplinary collaborations and communications in all aspects of health care for humans, animals and the environment 4 One Health Approach: The How? • Innovative strategy to promote multi‐sectoral and interdisciplinary application of knowledge -

Geographic Tools for Global Public Health

GEOGRAPHIC TOOLS FOR GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH AN ASSESSMENT OF AVAILABLE SOFTWARE MEASURE Evaluation www.cpc.unc.edu/measure MEASURE Evaluation is funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) through Cooperative Agreement GHA-A-00-08-00003-00 and is implemented by the Carolina Population Center at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, in partnership with Futures Group, ICF International, John Snow, Inc., Management Sciences for Health, and Tulane University. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States government. November 2013 MS-13-80 Acknowledgements This guide was prepared as a collaborative effort by the MEASURE Evaluation Geospatial Team, following a suggestion from the MEASURE GIS Working Group. We are grateful for the helpful comments and reviews provided by Covington Brown, consultant; Clara Burgert of MEASURE DHS; and by Marc Cunningham, Jen Curran, Andrew Inglis, John Spencer, James Stewart, and Becky Wilkes of MEASURE Evaluation. Carrie Dolan of AidData at the College of William and Mary and Jim Wilson in the Department of Geography at Northern Illinois University also reviewed the paper and provided insightful comments. We are grateful for general support from the Population Research Infrastructure Program awarded to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s Carolina Population Center (R24 HD050924) by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (NICHD). The inclusion of a software program in this document does not imply endorsement by the MEASURE GIS Working Group or its members; or by MEASURE Evaluation, the U.S. -

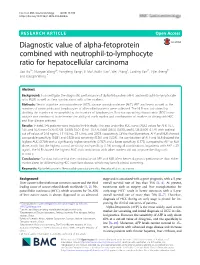

Diagnostic Value of Alpha-Fetoprotein Combined with Neutrophil-To

Hu et al. BMC Gastroenterology (2018) 18:186 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-018-0908-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Diagnostic value of alpha-fetoprotein combined with neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio for hepatocellular carcinoma Jian Hu1†, Nianyue Wang2†, Yongfeng Yang2,LiMa2, Ruilin Han3, Wei Zhang4, Cunling Yan3*, Yijie Zheng5* and Xiaoqin Wang1* Abstract Background: To investigate the diagnostic performance of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) as well as their combinations with other markers. Methods: Serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST), alanine aminotransferase (ALT), AFP and levels as well as the numbers of neutrophils and lymphocytes of all enrolled patients were collected. The NLR was calculated by dividing the number of neutrophils by the number of lymphocytes. Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis was conducted to determine the ability of each marker and combination of markers to distinguish HCC and liver disease patients. Results: In total, 545 patients were included in this study. The area under the ROC curve (AUC) values for AFP, ALT, AST, and NLR were 0.775 (0.738–0.810), 0.504 (0.461–0.547), 0.660 (0.618–0.699), and 0.738 (0.699–0.774) with optimal cut-off values of 24.6 ng/mL, 111 IU/mL, 27 IU/mL, and 2.979, respectively. Of the four biomarkers, AFP and NLR showed comparable specificity (0.881 and 0.858) and sensitivity (0.561 and 0.539). The combination of AFP and NLR showed the highest AUC (0.769) with a significantly higher sensitivity (0.767) and a lower specificity (0.773) compared to AFP or NLR alone, and it had the highest sum of sensitivity and specificity (1.54) among all combinations. -

Redalyc.Estado Actual De La Informatización De Los Procesos De

MEDISAN E-ISSN: 1029-3019 [email protected] Centro Provincial de Información de Ciencias Médicas de Santiago de Cuba Cuba Sagaró del Campo, Nelsa María; Jiménez Paneque, Rosa Estado actual de la informatización de los procesos de evaluación de medios de diagnóstico y análisis de decisión clínica MEDISAN, vol. 13, núm. 1, 2009 Centro Provincial de Información de Ciencias Médicas de Santiago de Cuba Santiago de Cuba, Cuba Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=368448451012 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Estado actual de la informatización de los procesos de evaluación de medios de diagnóstico y análisis de decisión clínica MEDISAN 2009;13(1) Facultad de Medicina No. 2, Santiago de Cuba, Cuba Estado actual de la informatización de los procesos de evaluación de medios de diagnóstico y análisis de decisión clínica Current state of the informatization of the evaluation processes of diagnostic means and analysis of clinical decision Dra. Nelsa María Sagaró del Campo 1 y Dra. C. Rosa Jiménez Paneque 2 Resumen La creación de un programa informático para la evaluación de medios de diagnóstico y el análisis de decisión clínica demandó indagar detenidamente acerca de la situación actual con respecto a la automatización de ambos procesos, todo lo cual se expone sintetizadamente en este artículo, donde se plantea que el tratamiento computacional de estos métodos y procedimientos puede calificarse hoy como disperso e incompleto.