Space Time Continuing Barry Guy Has Spent

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67

Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 Marc Howard Medwin A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music. Chapel Hill 2008 Approved by: David Garcia Allen Anderson Mark Katz Philip Vandermeer Stefan Litwin ©2008 Marc Howard Medwin ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT MARC MEDWIN: Listening in Double Time: Temporal Disunity and Structural Unity in the Music of John Coltrane 1965-67 (Under the direction of David F. Garcia). The music of John Coltrane’s last group—his 1965-67 quintet—has been misrepresented, ignored and reviled by critics, scholars and fans, primarily because it is a music built on a fundamental and very audible disunity that renders a new kind of structural unity. Many of those who study Coltrane’s music have thus far attempted to approach all elements in his last works comparatively, using harmonic and melodic models as is customary regarding more conventional jazz structures. This approach is incomplete and misleading, given the music’s conceptual underpinnings. The present study is meant to provide an analytical model with which listeners and scholars might come to terms with this music’s more radical elements. I use Coltrane’s own observations concerning his final music, Jonathan Kramer’s temporal perception theory, and Evan Parker’s perspectives on atomism and laminarity in mid 1960s British improvised music to analyze and contextualize the symbiotically related temporal disunity and resultant structural unity that typify Coltrane’s 1965-67 works. -

TOTAL MUSIC MEETING 2000 - 2008 International Artists Festival of Improvised Music

TOTAL MUSIC MEETING 2000 - 2008 International Artists Festival of Improvised Music CONCERTS of Artists contributing (in alphabetical order) Name Instrument Country TMM-Year of Performance Sophie Agnel piano France TMM 2007 Boris Aljinovic actor/speaker w/ KÜÖ Germany TMM 2003 Armand Angster cl, bcl, cbcl France TMM 2001, 2004, 2006 Serge Baghdassarians e-g, live electronics Germany TMM 2000, 2002 Boris Baltschun e-g, live electronics Germany TMM 2000, 2002 Richard Barrett sampl. keyboard, electr England/Germany TMM 2005, 2008 Irena Bart-Greiner soprano Germany TMM 2003, 2004 Johannes Bauer trombone Germany TMM 2000, 2002, 2004 Konrad Bauer trombone Germany TMM 2001, 2002 Matthias Bauer double-bass Germany TMM 2007 Carlos Bechegas picc fl, alto-, C-soprano Portugal TMM 2002 Han Bennink dr, perc The Netherlands TMM 2004 Tiziana Bertoncini violin Italy TMM 2002 Lucas Böttcher digital media Germany TMM 2007 Gerard Bouwhuis p, keyboard The Netherlands TMM 2005 Alberto Braida piano Italy TMM 2001, 2004 Peter Brötzmann reeds Germany TMM 2000 Jerome Bryerton dr, perc USA TMM 2002 Tony Buck dr, live electronics Australia/Germany TMM 2000 John Butcher reeds England TMM 2005 Jesus Canneloni reeds Germany TMM 2005 Rüdiger Carl cl, acc Germany TMM 2000, 2001 Carlo Caratelli harpsichord Italy TMM 2004 Andrea Carlon double-bass Italy TMM 2004 Lawrence Casserley computer processing England TMM 2007 Thomas Castro visuals/design image The Netherlands TMM 2005 Tomek Choloniewski perc Poland TMM 2008 Günter Christmann cello, tb Germany TMM 2002, 2003 Melissa -

Kenny Wheeler Gnu High Mp3, Flac, Wma

Kenny Wheeler Gnu High mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Jazz Album: Gnu High Country: Germany Released: 1976 Style: Contemporary Jazz MP3 version RAR size: 1354 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1292 mb WMA version RAR size: 1647 mb Rating: 4.7 Votes: 634 Other Formats: MPC APE AA TTA MP3 MMF AAC Tracklist A Heyoke 21:47 B1 'Smatter 5:56 B2 Gnu Suite 12:47 Companies, etc. Phonographic Copyright (p) – ECM Records GmbH Published By – ECM Verlag Recorded At – Generation Sound Studios Credits Bass – Dave Holland Composed By – Kenny Wheeler Drums – Jack DeJohnette Engineer – Tony May Flugelhorn – Kenny Wheeler Layout – B. Wojirsch* Mixed By – Martin Wieland Photography By [Cover] – Tadayuki Naito* Piano – Keith Jarrett Producer – Manfred Eicher Notes Recorded June 1975, Generation Sound Studios, New York City. An ECM Production ℗ 1976 ECM Records GmbH Printed in W. Germany Barcode and Other Identifiers Matrix / Runout (Side A runout, stamped): ST-ECM 1069-A Matrix / Runout (Side B runout, stamped): ST-ECM 1069-B Rights Society: GEMA Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year ECM ECM 1069, 825 Kenny Gnu High (CD, ECM 1069, 825 Records, Germany Unknown 591-2 Wheeler Album, RE) 591-2 ECM Records Kenny Gnu High (LP, 25MJ 3327 ECM Records 25MJ 3327 Japan 1976 Wheeler Album) ECM ECM 1069, ECM Kenny Gnu High (LP, ECM 1069, ECM Records, Germany Unknown 1069 ST Wheeler Album, RE) 1069 ST ECM Records ECM ECM 1069, Kenny Gnu High (CD, ECM 1069, Records, US 2008 B0011628-02 Wheeler Album, RE, Dig) B0011628-02 ECM -

Peter Johnston 2011

The London School Of Improvised Economics - Peter Johnston 2011 This excerpt from my dissertation was included in the reader for the course MUS 211: Music Cultures of the City at Ryerson University. Introduction The following reading is a reduction of a chapter from my dissertation, which is titled Fields of Production and Streams of Conscious: Negotiating the Musical and Social Practices of Improvised Music in London, England. The object of my research for this work was a group of musicians living in London who self-identified as improvisers, and who are part of a distinct music scene that emerged in the mid-1960s based on the idea of free improvisation. Most of this research was conducted between Sept 2006 and June 2007, during which time I lived in London and conducted interviews with both older individuals who were involved in the creation of this scene, and with younger improvisers who are building on the formative work of the previous generation. This chapter addresses the practical aspects of how improvised music is produced in London, and follows a more theoretical analysis in the previous chapters of why the music sounds like it does. Before moving on to the main content, it will be helpful to give a brief explanation of two of the key terms that occur throughout this chapter: “free improvisation” and the “improvised music field.” “Free improvisation” refers to the creation of musical performances without any pre- determined materials, such as form, tonality, melody, or rhythmic feel. This practice emerged out of developments in jazz in the late 1950s and early 1960s, particularly in the work of Ornette Coleman and Cecil Taylor, who began performing music without using the song-forms, harmonic progressions, and steady rhythms that characterized jazz until that time. -

3H3b &Eotercammemc

teptexber 13, 197G n mcry, 3h3b & eotercammemc ' ; i i -- JG2Z5 G3JJ Vy OTil 1 1 If I ( nil if f i If tI HI- ..I 11 v "l( II II k I..V J L" J I i V uvu Lauy M Xiw the material bi isvzzs there is never doubt whose album it really releasing psckr. Yet, any Siice there have been over 20 albums of this type mar- If yca're fcto are more 251 ca is. Tens and ttzs it is Wheeler's comrnasdsig pre- jzn, tlre jped tin, keted ia the last four months, a complete review is im- fa lisccla this astena thaa ever before. tence ca the Ihil horn that drives this music into new fre-qaen- and possible. Local dubs sre bcd? sets triS cy. territories, bis horn Caching with dramatic purpose Arista com- jrrz fccreas Spontaneous Combustion from Savoy Area jazz mtr.scfcrrs arc a ? to show- warmth. grtrj bines the first two sessions ever recorded by the great case their tslssti st the Zoo Car's masiSLIy KFlfQ Add l!asfred Eicfcers flawless production and you psa. Cannonba3 Adderiey. These 1955 recordings find Adder-ley-'s deovies two hours jazz-orient- ed one the best acoustic efforts. every to come wi& cf year's Bird-inspir- Ssnday cht cp JCSHhenched and ed sax wiA such mon- musie, and the word is that the soca wi3 be ex- Kcfc!e &bzt Gcsdea prcsram by Horace Silver and, of course, tended another hour. - John Gordon makes a notable debut. Step by Step, sters as Kenny Clarke, Nat. -

Malcolm Braff's Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation

Malcolm Braff’s Approach to Rhythm for Improvisation: Definition, Analysis and Aesthetic Daniel Jacobus Steyn de Wet A dissertation submitted to the faculty of humanities, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of MMUS. Johannesburg 2017 Plagiarism Declaration 1. I know that plagiarism is wrong. Plagiarism is to use another’s work and to pretend that it is one’s own. 2. I have used the author date convention for citation and referencing. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this thesis from the work or works of other people has been acknowledged through citation and reference. 3. The essay is my own work. 4. I have not allowed and will not allow anyone to copy my work with the intention of passing it off as his or her own work. _______________________ _________________________ Signature Date Human Research Ethics Clearance (non-medical) Certificate Number: 2 Acknowledgements I would like to thank my friends and family for the support they have shown through this time. I further thank the various supervisors and co-supervisors who have at some point had some level of input into this study. On the practical side of my study I thank Malcolm Ney for the high level of classical training that I have received. I thank Andre Petersen for his input into the jazz specific aspects of my performance training. Special thanks to Dr. Carlo Mombelli for the training I received in his ensembles and at his home with regard to beautiful and improvised music. Thanks also go to the supervisors for the majority of my proposal phase Dr. -

Printcatalog Realdeal 3 DO

DISCAHOLIC auction #3 2021 OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! This is the 3rd list of Discaholic Auctions. Free Jazz, improvised music, jazz, experimental music, sound poetry and much more. CREATIVE MUSIC the way we need it. The way we want it! Thank you all for making the previous auctions great! The network of discaholics, collectors and related is getting extended and we are happy about that and hoping for it to be spreading even more. Let´s share, let´s make the connections, let´s collect, let´s trim our (vinyl)gardens! This specific auction is named: OLD SCHOOL: NO JOKE! Rare vinyls and more. Carefully chosen vinyls, put together by Discaholic and Ayler- completist Mats Gustafsson in collaboration with fellow Discaholic and Sun Ra- completist Björn Thorstensson. After over 33 years of trading rare records with each other, we will be offering some of the rarest and most unusual records available. For this auction we have invited electronic and conceptual-music-wizard – and Ornette Coleman-completist – Christof Kurzmann to contribute with some great objects! Our auction-lists are inspired by the great auctioneer and jazz enthusiast Roberto Castelli and his amazing auction catalogues “Jazz and Improvised Music Auction List” from waaaaay back! And most definitely inspired by our discaholic friends Johan at Tiliqua-records and Brad at Vinylvault. The Discaholic network is expanding – outer space is no limit. http://www.tiliqua-records.com/ https://vinylvault.online/ We have also invited some musicians, presenters and collectors to contribute with some records and printed materials. Among others we have Joe Mcphee who has contributed with unique posters and records directly from his archive. -

Music Outside? the Making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde 1968-1973

Banks, M. and Toynbee, J. (2014) Race, consecration and the music outside? The making of the British jazz avant-garde 1968-1973. In: Toynbee, J., Tackley, C. and Doffman, M. (eds.) Black British Jazz. Ashgate: Farnham, pp. 91-110. ISBN 9781472417565 There may be differences between this version and the published version. You are advised to consult the publisher’s version if you wish to cite from it. http://eprints.gla.ac.uk/222646/ Deposited on 28 August 2020 Enlighten – Research publications by members of the University of Glasgow http://eprints.gla.ac.uk Race, Consecration and the ‘Music Outside’? The making of the British Jazz Avant-Garde: 1968-1973 Introduction: Making British Jazz ... and Race In 1968 the Arts Council of Great Britain (ACGB), the quasi-governmental agency responsible for providing public support for the arts, formed its first ‘Jazz Sub-Committee’. Its main business was to allocate bursaries usually consisting of no more than a few hundred pounds to jazz composers and musicians. The principal stipulation was that awards be used to develop creative activity that might not otherwise attract commercial support. Bassist, composer and bandleader Graham Collier was the first recipient – he received £500 to support his work on what became the Workpoints composition. In the early years of the scheme, further beneficiaries included Ian Carr, Mike Gibbs, Tony Oxley, Keith Tippett, Mike Taylor, Evan Parker and Mike Westbrook – all prominent members of what was seen as a new, emergent and distinctively British avant-garde jazz scene. Our point of departure in this chapter is that what might otherwise be regarded as a bureaucratic footnote in the annals of the ACGB was actually a crucial moment in the history of British jazz. -

How to Play in a Band with 2 Chordal Instruments

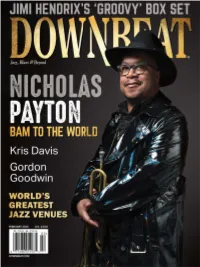

FEBRUARY 2020 VOLUME 87 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

The Creative Application of Extended Techniques for Double Bass in Improvisation and Composition

The creative application of extended techniques for double bass in improvisation and composition Presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Music) Volume Number 1 of 2 Ashley John Long 2020 Contents List of musical examples iii List of tables and figures vi Abstract vii Acknowledgements viii Introduction 1 Chapter 1: Historical Precedents: Classical Virtuosi and the Viennese Bass 13 Chapter 2: Jazz Bass and the Development of Pizzicato i) Jazz 24 ii) Free improvisation 32 Chapter 3: Barry Guy i) Introduction 40 ii) Instrumental technique 45 iii) Musical choices 49 iv) Compositional technique 52 Chapter 4: Barry Guy: Bass Music i) Statements II – Introduction 58 ii) Statements II – Interpretation 60 iii) Statements II – A brief analysis 62 iv) Anna 81 v) Eos 96 Chapter 5: Bernard Rands: Memo I 105 i) Memo I/Statements II – Shared traits 110 ii) Shared techniques 112 iii) Shared notation of techniques 115 iv) Structure 116 v) Motivic similarities 118 vi) Wider concerns 122 i Chapter 6: Contextual Approaches to Performance and Composition within My Own Practice 130 Chapter 7: A Portfolio of Compositions: A Commentary 146 i) Ariel 147 ii) Courant 155 iii) Polynya 163 iv) Lento (i) 169 v) Lento (ii) 175 vi) Ontsindn 177 Conclusion 182 Bibliography 191 ii List of Examples Ex. 0.1 Polynya, Letter A, opening phrase 7 Ex. 1.1 Dragonetti, Twelve Waltzes No.1 (bb. 31–39) 19 Ex. 1.2 Bottesini, Concerto No.2 (bb. 1–8, 1st subject) 20 Ex.1.3 VerDi, Otello (Act 4 opening, double bass) 20 Ex. -

Contact: a Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) Citation

Contact: A Journal for Contemporary Music (1971-1988) http://contactjournal.gold.ac.uk Citation Barry. Malcolm. 1977-1978. ‘Review of Company 1 (Maarten van Regteren Altena, Derek Bailey, Tristan Honsinger, Evan Parker) and Company 2 (Derek Bailey, Anthony Braxton, Evan Parker)’. Contact, 18. pp. 36-39. ISSN 0308-5066. ! Director Professor Frederick Rimmer MA B M us FRco Secretary and Librarian James. L McAdam BM us FRco Scottish R Music Archive with the support of the Scottish Arts Council for the documentation and study of Scottish music information on all matters relating to Scottish composers and Scottish music printed and manuscript scores listening facilities: tape and disc recordings Enquiries and visits welcomed: full-time staff- Mr Paul Hindmarsh (Assistant Librarian) and Miss Elizabeth Wilson (Assistant Secretary) Opening Hours: Monday to Friday 9.30 am- 5.30 pm Monday & Wednesday 6.00-9.00 pm Saturday 9.30 am- 12.30 pm .. cl o University of Glasgow 7 Lily bank Gdns. Glasgow G 12 8RZ Telephone 041-334 6393 37 INCUS it RECORDS INCUS RECORDS/ COMPATIBLE RECORDING AND PUBLISHING LTD. is a self-managed company owned and operated by musicians. The company was founded in 1970, motivated partly by the ideology of self-determination and partly by the absence of an acceptable alternative. The spectrum of music issued has been broad, but the musical policy of the company is centred on improvisation. Prior to 1970 the innovative musician had a relationship with the British record industry that could only be improved on. To be offered any chance to make a record at all was already a great favour and somehow to question the economics (fees, royalties, publishing) would certainly have been deemed ungrateful. -

A More Attractive ‘Way of Getting Things Done’ Freedom, Collaboration and Compositional Paradox in British Improvised and Experimental Music 1965-75

A more attractive ‘way of getting things done’ freedom, collaboration and compositional paradox in British improvised and experimental music 1965-75 Simon H. Fell A thesis submitted to the University of Huddersfield in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Huddersfield September 2017 copyright statement i. The author of this thesis (including any appendices and/or schedules to this thesis) owns any copyright in it (the “Copyright”) and he has given The University of Huddersfield the right to use such Copyright for any administrative, promotional, educational and/or teaching purposes. ii. Copies of this thesis, either in full or in extracts, may be made only in accordance with the regulations of the University Library. Details of these regulations may be obtained from the Librarian. This page must form part of any such copies made. iii. The ownership of any patents, designs, trade marks and any and all other intellectual property rights except for the Copyright (the “Intellectual Property Rights”) and any reproductions of copyright works, for example graphs and tables (“Reproductions”), which may be described in this thesis, may not be owned by the author and may be owned by third parties. Such Intellectual Property Rights and Reproductions cannot and must not be made available for use without the prior written permission of the owner(s) of the relevant Intellectual Property Rights and/or Reproductions. 2 abstract This thesis examines the activity of the British musicians developing a practice of freely improvised music in the mid- to late-1960s, in conjunction with that of a group of British composers and performers contemporaneously exploring experimental possibilities within composed music; it investigates how these practices overlapped and interpenetrated for a period.