Cunard Building, First Floor Interior

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enquiries To: Information Team Our Ref: FOI608454 Request-496130

Enquiries to: Information Team Our Ref: FOI608454 [email protected] Dear Mr Grant Freedom of Information Request 608454 Thank you for your recent request received 9 July 2018. Your request was actioned under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 in which you requested the following information – Can you please provide the following information under the Freedom of Information Act: - address of residential properties where the owner does not live in Liverpool - the names of the owners of these properties - the contact address for these owners - the listed number of bedrooms and reception rooms for these properties. Response: Liverpool City Council would advise as follows – 1. Please refer to the appended document. 2. This information is considered to constitute personal data and as such is being withheld from disclosure under the provisions of the Exemption set out at Section 40(2) Freedom of Information Act 2000. 3. This information is considered to constitute personal data and as such is being withheld from disclosure under the provisions of the Exemption set out at Section 40(2) Freedom of Information Act 2000. 4. This information is not recorded as there is no operational or legislative requirement for us to do so. To extract this information would require a manual review of all applications (in excess of 20,000 applications and, allowing for 1 minute to review each application, would require substantially in excess of 18 hours to complete. In accordance with the provisions of Section 12 FOIA the City Council therefore declines to provide this information on the basis that substantially more time than the 18 hours prescribed by legislation would be required to fulfil your request. -

BOROUGH BUILDINGS, WATER ST (1859 – Ca. 1970)

Water Street in the 1880s with Borough Buildings in the centre. Photo courtesy of Colin Wilkinson. WALKING ON WATER STREET Graham Jones explores the histories of various buildings in the Water Street area. Part 3 – BOROUGH BUILDINGS, WATER ST (1859 – ca . 1970) 1 In its early years Borough Buildings lived gracefully between two buildings which captured greater attention: Oriel Chambers (1864) at 14 Water Street, for which Peter Ellis was so rudely criticised when the building was originally constructed, and Middleton Buildings (ca. 1859) at 8 Water Street which, until 1916, was the home of the Cunard Line. The comment in Charles Reilly's 1921 tour of Water Street, 2 – “After the empty site, where the old Cunard Building was, comes the oddest building in Liverpool – Oriel Chambers,...” gives the impression that Borough Buildings did not exist. But it did, and during the century of its existence it provided office accommodation for The Liverpool Steam Ship Owners' Association, the American Chamber of Commerce and a variety of important businesses and shipping lines. Trade between America and the U.K.'s premier port had become so important by the end of the 18th century that an American Chamber of Commerce was formed in 1801. The first three attempts at laying a transatlantic cable between 1857 and 1865 had ended in failure when the cables broke or developed faults, but success was finally achieved in 1866, with the Great Eastern being one of the ships involved in cable laying. On September 20th of that year, following a letter from the Liverpool Chamber of Commerce regarding their proposal for a public dinner to celebrate the laying of the cable, the American Chamber met at Borough Buildings (to which they had moved their offices in 1864 from Exchange Street West). -

Heritage Month Low Res 670173165.Pdf

£1 Welcome to Liverpool Heritage Open Month! Determined Heritage Open Days are managed nationally by to build on the Heritage Open Days National Partnership the success and funded by English Heritage. of Heritage Heritage Open Month could never happen Open Days, without the enthusiasm and expertise of local celebrating people. Across England thousands of volunteers England’s will open their properties, organise activities fantastic and events and share their knowledge. To architecture everyone in Liverpool who has contributed and heritage, Liverpool is once to the fantastic 2013 Heritage Open Month again extending its cultural heritage programme we would like to say thank you. programme throughout September. The information contained in this booklet was In 2013 over 100 venues and correct at the time of print but may be subject organisations across the city are to change. involved in this year’s programme and buildings of a variety of architectural Further events may have also been added style and function will open their to the programme. Full details of the doors offering a once-a-year chance to Heritage Open Month programme and discover hidden treasures and enjoy a up to date information can be viewed on wide range of tours, and participate in VisitLiverpool.com/heritageopenmonth events bringing history alive. or call 0151 233 2008. For the national One of the attractions new to 2013 Heritage Open Days programme please is the Albany Building, former cotton go to broker’s meeting place with its stunning www.heritageopendays.org.uk cast iron work, open air staircase. or call 0207 553 9290 There is something to delight everyone during Heritage Open Month with new ways to experience the heritage of Liverpool for all the family. -

Edgar De Leon, Esq. the De Leon Firm, PLLC 26 Broadway, Suite 1700 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] (212) 747-0200

Edgar De Leon, Esq. The De Leon Firm, PLLC 26 Broadway, Suite 1700 New York, NY 10004 [email protected] (212) 747-0200 Edgar De Leon is a graduate of the Fordham University School of Law (J.D.) and Hunter College (M.S. & B.A.). He has worked as a Detective-Sergeant and an attorney for the New York City Police Department (NYPD). His assignments included investigating hate-motivated crimes for the Chief of Department and allegations of corruption and serious misconduct for the Deputy Commissioner of Internal Affairs and the Chief of Detectives. While assigned to the NYPD Legal Bureau, Mr. De Leon litigated both criminal and civil matters on behalf of the Police Department. He conducted legal research on matters concerning police litigation and initiatives and advised members of the department on matters relating to the performance of their official duties. Mr. De Leon has counseled NYPD executives and law enforcement and community-based organizations domestically and internationally concerning policy and procedure development in police-related subjects, including cultural diversity. In 2005, Mr. De Leon was part of an international team that traveled to Spain and Hungary. Working under the auspices of the Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights (ODIHR), a subdivision of the Organization for Cooperation and Strategy in Europe (OCSE), the team drafted a curriculum and implemented the first-ever training program for police officers in the European Union concerning the handling and investigation of hate crimes. In January 1999, Mr. De Leon retired from the NYPD with the rank of Sergeant S.A. -

Guide to Liverpool Waterfront

Guide to Liverpool Waterfront “Three Graces” – Together the Royal Liver Building, Cunard Building and the Port of Liverpool Building make up the Mersey’s ‘Three Graces’ and are at the architectural centre of Liverpool’s iconic waterfront. A massive engineering project has recently extended the canal in front of these three buildings, adding beautifully landscaped seating areas and viewpoints along the canal and the river. Museum of Liverpool – this brand new museum, opened in 2011 is a magnificent addition to Liverpool’s waterfront. Celebrating the origins and heritage of the city, it features collections from National Museums Liverpool that have never been seen before. Otterspool Promenade – The construction of Otterspool Promenade (1950) provided both a new amenity for Liverpool and an open space dividend from the disposal of Mersey Tunnel spoil and household waste; a project repeated three decades later to reclaim the future International Garden Festival site. A favourite with kite fliers this often overlooked wide open space is perfect for views of the river and picnics Antony Gormley’s “Another Place” - These spectacular sculptures by Antony Gormley are on Crosby beach, about 10 minutes out of Liverpool. Another Place consists of 100 cast-iron, life-size figures spread out along three kilometres of the foreshore, stretching almost one kilometre out to sea. The Another Place figures - each one weighing 650 kilos - are made from casts of the artist's own body standing on the beach, all of them looking out to sea, staring at the horizon in silent expectation. Mersey Ferry - There's no better way to experience Liverpool and Merseyside than from the deck of the world famous Mersey Ferry listening to the commentary. -

Dover Society Trip to Liverpool

16 Dover Society Trip to Liverpool Friday 14th to Monday 17th September 2018 Introduction Sheila Cope he fact that this trip took place at Tall is due to Patricia's sheer determination and perseverance as, together with Patrick's support, she gradually found more participants, even beyond the deadline, so that the event could go ahead without incurring a loss to The Society. I trust that the great success of the venture justified Pat's efforts in the end and those of us who were able to go owe her a real debt of gratitude for providing such an interesting and enjoyable experience. Albert Dock Liverpool We have found the coach firm of Leo's Pride was a little tedious due to heavy traffic and reliable and efficient on previous occasions. the homeward journey was delayed by an Janet was our driver this time. One would accident on the M25, but these were mere never have guessed that she had not driven blips which only served to emphasise how on this particular trip before, yet we were trouble-free and pleasurable the whole trip able to relax, feeling assured that we were had been. And what excellent value for in safe hands. Janet's skill in manoeuvring money! There was even an extra bonus for such a large coach around Liverpool and four members who were able to meet up Chester at the bidding of the City Guides on with their grandchildren. board was most admirable. National Memorial Arboretum Our hotel was comfortable with helpful staff Friday 14th who remedied our minor problems. -

TM 3.1 Inventory of Affected Businesses

N E W Y O R K M E T R O P O L I T A N T R A N S P O R T A T I O N C O U N C I L D E M O G R A P H I C A N D S O C I O E C O N O M I C F O R E C A S T I N G POST SEPTEMBER 11TH IMPACTS T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. 3.1 INVENTORY OF AFFECTED BUSINESSES: THEIR CHARACTERISTICS AND AFTERMATH This study is funded by a matching grant from the Federal Highway Administration, under NYSDOT PIN PT 1949911. PRIME CONSULTANT: URBANOMICS 115 5TH AVENUE 3RD FLOOR NEW YORK, NEW YORK 10003 The preparation of this report was financed in part through funds from the Federal Highway Administration and FTA. This document is disseminated under the sponsorship of the U.S. Department of Transportation in the interest of information exchange. The contents of this report reflect the views of the author who is responsible for the facts and the accuracy of the data presented herein. The contents do no necessarily reflect the official views or policies of the Federal Highway Administration, FTA, nor of the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council. This report does not constitute a standard, specification or regulation. T E C H N I C A L M E M O R A N D U M NO. -

Cunard Line · Reisebureau G

LIST OF PASSENGERS :m .~ ~ " 1l •t . '' c'"'~· c"' '· ;;s. c- ~qut anta QUADRUPLE SCREW- GROSS TONNAGE, 45,647 FROM NEW YORK TUESDAY, MARCH 20th, 1923 TO CHERBOURG AND SOUTHAMPTON Information for Passensers (Subject to ChanE,e) Public Telephone-The steamer is equipped with a telephone, conveniently located, which may be used by passengers until discon nection (without notice) a few minutes before departure. Telephones with booths and Operators are also provided on the New York piers. Meals will be served at the following times in the First-Class Dining Saloon: Breakfast from 8 to 10 a.m. Luncheon from 1 to 2 p.m. Dinner . from 7 to 9 p.m. and in Second-Class Dining Saloon: Breakfast from 7:30 to 8:30 a.m. Luncheon from 12 :30 to 1 :30 p.m. Dinner from 6 to 7 p.m .. The Bars in the First-Class will not be open later than 11 :30 p.m. and in the Second-Class not later than 11 p.m., but it is within the discretion of the Commander to close them during the voyage at any time should he consider this course desirable. Seats at Table-Application may be made at any of the Chief Offices in advance or to the Se.__·ond Steward on board the steamer on day of sailing. Chairs and Rugs may be hired at a cost of $1.50 each, on .application to the Deck Steward. Each rug is contained in a sealed cardboard box, and bears a serial number worked into the material so that passengers will have no difficulty in identifying their rugs. -

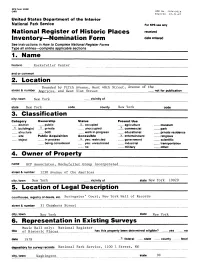

National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination

NPS Form 10-900 (3-82) OMB No. 1024-0018 Expires 10-31-87 United States Department off the Interior National Park Service For NPS use only National Register of Historic Places received Inventory Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries complete applicable sections____________ 1. Name historic Rockefeller Center and or common 2. Location Bounded by Fifth Avenue, West 48th Street, Avenue of the street & number Americas, and West 51st Street____________________ __ not for publication city, town New York ___ vicinity of state New York code county New York code 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public x occupied agriculture museum x building(s) x private unoccupied x commercial park structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible _ x entertainment religious object in process x yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no military other: 4. Owner of Property name RCP Associates, Rockefeller Group Incorporated street & number 1230 Avenue of the Americas city, town New York __ vicinity of state New York 10020 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Surrogates' Court, New York Hall of Records street & number 31 Chambers Street city, town New York state New York 6. Representation in Existing Surveys Music Hall only: National Register title of Historic Places has this property been determined eligible? yes no date 1978 federal state county local depository for survey records National Park Service, 1100 L Street, NW ^^ city, town Washington_________________ __________ _ _ state____DC 7. Description Condition Check one Check one x excellent deteriorated unaltered x original s ite good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed Describe the present and original (iff known) physical appearance The Rockefeller Center complex was the final result of an ill-fated plan to build a new Metropolitan Opera House in mid-town Manhattan. -

26 Broadway Educational Campus

The landmarked building in Lower Manhattan gets a second life as a 26 Broadway school thanks to its steel structure and an innovative adaptive reuse plan. Educational FOR THE PAST SEVERAL YEARS, the landmarked transformed from the oil giant’s Carrère and Hast- ings-designed headquarters into a lively academic Campus complex for secondary students in Lower Manhat- tan. The third academic institution to be located in the building, it occupies 104,000 square feet of and adds nearly 700 high school seats to what SCA complex, which also includes the Urban Assembly - Ciardullo Associates, who has worked extensively this longstanding relationship is why Ciardullo was allowed to have a bit of fun with the campus, trans- forming an underused mechanical courtyard into a dramatic double-height, steel-framed gymnasium. most of the building’s existing structure is steel, for a gymnasium into the columns already in place. literally put the beams anywhere within the steel structure. If you had a concrete structure, you’d have a problem analyzing it structurally because you don’t know what reinforcing steel is in the concrete frame. You would have to drill into the concrete to the building, we could create a large space that could function as a gym and we could bring in light through a skylight,” says Ciardullo. Though the idea of giving Manhattan students an indoor gym was a novel one, the execution of it proved relatively window openings two stories above street level, the open courtyard space. There, the beams were welded at one end to existing steel columns on the portion of the building built in 1921. -

J. & W. Seligman & Company Building

Landmarks Preservation Commission February 13, 1996, Designation List 271 LP-1943 J. & W. SELIGMAN & COMPANY BUILDING (later LEHMAN BROTHERS BUILDING; now Banca Commerciale Italiana Building), 1 William Street (aka 1-9 William Street, 1-7 South William Street, and 63-67 Stone Street), Borough of Manhattan. Built 1906-07; Francis H. Kimball and Julian C. Levi, architects; George A. Fuller Co., builders; South William Street facade alteration 1929, Harry R. Allen, architect; addition 1982-86, Gino Valle, architect. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 29, Lot 36. On December 12, 1995, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the J. & W. Seligman & Company Building (later Lehman Brothers Building; now Banca Commerciale Italiana Building) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 5). The hearing was continued to January 30, 1996 (Item No. 4). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Nine witnesses spoke in favor of designation, including representatives of Manhattan Borough President Ruth Messinger, Council Member Kathryn Freed, Municipal Art Society, New York Landmarks Conservancy, Historic Districts Council, and New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects. In addition, the Commission has received a resolution from Community Board 1 in support of designation. Summary The rusticated, richly sculptural, neo-Renaissance style J. & W. Seligman & Company Building, designed by Francis Hatch Kimball in association with Julian C. Levi and built in 1906-07 by the George A. Fuller Co. , is located at the intersection of William and South William Streets, two blocks off Wall Street. -

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York

Rockefeller Center Complex Master Plan and Exterior Rehabilitations New York, New York Developed for the purpose of planning maintenance and capital improvement projects, Hoffmann National Trust for Architects’ Exterior Rehabilitation Master Plan for Rockefeller Center encompassed the nineteen Historic Preservation buildings of John D. Rockefeller Jr.’s 22-acre “city within a city.” The buildings are subject not only to Honor Award New York City Department of Buildings regulations, including New York City Local Law 10 of 1980 GE Building at Rockefeller and Local Law 11 of 1998 (LL10/LL11), but also to Landmark Commission restrictions, making Center - Restoration rehabilitation planning particularly challenging. Hoffmann Architects’ Master Plan addressed these considerations, while achieving even budgeting across the years. The award-winning rehabilitation program included facade and curtain wall restoration, roof replacements, waterproofing, and historic preservation for this National Historic Landmark and centerpiece of New York City. In conjunction with the Master Plan, Hoffmann Architects developed specific rehabilitation solutions for the Center’s structures, including: GE Building, Sculpture Restoration and Building Envelope Rehabilitation Radio City Music Hall, Roof Replacement and Facade Restoration La Maison Francaise and The British Empire Building, Facade Evaluations and Cleaning Channel Gardens and Lower Plaza/Skating Rink, Survey and Rehabilitation Design International Building, Facade Restoration and Roof Replacement Simon