HAGEN, D.A.: Orson Rehearsed 8.574186

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Orson Welles: CHIMES at MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 Min

October 18, 2016 (XXXIII:8) Orson Welles: CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT (1965), 115 min. Directed by Orson Welles Written by William Shakespeare (plays), Raphael Holinshed (book), Orson Welles (screenplay) Produced by Ángel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman Music Angelo Francesco Lavagnino Cinematography Edmond Richard Film Editing Elena Jaumandreu , Frederick Muller, Peter Parasheles Production Design Mariano Erdoiza Set Decoration José Antonio de la Guerra Costume Design Orson Welles Cast Orson Welles…Falstaff Jeanne Moreau…Doll Tearsheet Worlds" panicked thousands of listeners. His made his Margaret Rutherford…Mistress Quickly first film Citizen Kane (1941), which tops nearly all lists John Gielgud ... Henry IV of the world's greatest films, when he was only 25. Marina Vlady ... Kate Percy Despite his reputation as an actor and master filmmaker, Walter Chiari ... Mr. Silence he maintained his memberships in the International Michael Aldridge ...Pistol Brotherhood of Magicians and the Society of American Tony Beckley ... Ned Poins and regularly practiced sleight-of-hand magic in case his Jeremy Rowe ... Prince John career came to an abrupt end. Welles occasionally Alan Webb ... Shallow performed at the annual conventions of each organization, Fernando Rey ... Worcester and was considered by fellow magicians to be extremely Keith Baxter...Prince Hal accomplished. Laurence Olivier had wanted to cast him as Norman Rodway ... Henry 'Hotspur' Percy Buckingham in Richard III (1955), his film of William José Nieto ... Northumberland Shakespeare's play "Richard III", but gave the role to Andrew Faulds ... Westmoreland Ralph Richardson, his oldest friend, because Richardson Patrick Bedford ... Bardolph (as Paddy Bedford) wanted it. In his autobiography, Olivier says he wishes he Beatrice Welles .. -

Press Release

PRESS RELEASE The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum 4079 Albany Post Road, Hyde Park, NY 12538-1917 www.fdrlibrary.marist.edu 1-800-FDR-VISIT October 14, 2008 FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Cliff Laube (845) 486-7745 Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library Author Talk and Film: Susan Quinn Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times HYDE PARK, NY -- The Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum is pleased to announce that Susan Quinn, author of Furious Improvisation: How the WPA and a Cast of Thousands Made High Art out of Desperate Times, will speak at the Henry A. Wallace Visitor and Education Center on Sunday, October 26 at 2:00 p.m. Following the talk, Ms. Quinn will be available to sign copies of her book. Furious Improvisation is a vivid portrait of the turbulent 1930s and the Roosevelt Administration as seen through the Federal Theater Project. Under the direction of Hallie Flanagan, formerly of the Vassar Experimental Theatre in Poughkeepsie, New York, the Federal Theater Project was a small but highly visible part of the vast New Deal program known as the Works Projects Administration. The Federal Theater Project provided jobs for thousands of unemployed theater workers, actors, writers, directors and designers nurturing many talents, including Orson Welles, John Houseman, Arthur Miller and Richard Wright. At the same time, it exposed a new audience of hundreds of thousands to live theatre for the first time, and invented a documentary theater form called the Living Newspaper. In 1939, the Federal Theater Project became one of the first targets of the newly-formed House Un-American Activities Committee, whose members used unreliable witnesses to demonstrate that it was infested with Communists. -

CAMPANADAS a MEDIA NOCHE - CHIMES at MIDNIGHT / 1966 (As Badaladas Da Meia-Noite)

CINEMATECA PORTUGUESA-MUSEU DO CINEMA REVISITAR OS GRANDES GÉNEROS - A COMÉDIA (PARTE III): O RISO 2 e 16 de dezembro de 2020 CAMPANADAS A MEDIA NOCHE - CHIMES AT MIDNIGHT / 1966 (As Badaladas da Meia-Noite) um filme de Orson Welles Realização: Orson Welles / Argumento: Orson Welles, segundo as peças de William Shakespeare, “Ricardo II”, “Henrique IV - Parte 1”, “Henrique IV - Parte 2”, “Henrique V”, “As Alegres Comadres de Windsor”, e o livro “Crónicas da Inglaterra, Escócia e Irlanda” de Raphael Holinshed / Fotografia: Edmond Richard / Musical Original: Angelo Francesco Lavagnino / Montagem: Elena Jaumandreu, Fritz Muller, Peter Parasheles / Direcção Artística: José António de la Guerra / Figurinos: Orson Welles / Director de Segunda equipa: Jesus Franco / Intérpretes: Orson Welles (Falstaff), Jeanne Moreau (Doll Tearsheet), Margaret Rutherford (Mistress Quickly), John Gielgud (Henrique IV), Marina Vlady (Kate Percy), Walter Chiari (Mr. Silence), Michael Aldridge (Pistol), Jeremy Rowe (Príncipe John), Alan Webb (Shallow), Fernando Rey (Worchester), Keith Baxter (Príncipe Hall), Norman Rodway (Henry “Hotspur” Percy), José Nieto (Northumberland), Andrew Faulds (Westmoreland), Patrick Bedford (Bardolph), Beatrice Welles (pagem de Falstaff). Narrador: Ralph Richardson. Produção: Angel Escolano, Emiliano Piedra, Harry Saltzman / Cópia: da Cinemateca Portuguesa- Museu do Cinema, 35mm, preto e branco, legendas em português, 113 minutos / Estreia Mundial: Festival Internacional de Cinema de Cannes, em 8 de Maio de 1966 / Estreia em Portugal: Estúdio 444, em 5 de Outubro de 1967 _____________________________ De toda a carreira de Orson Welles, talvez o seu filme mais pessoal seja Chimes at Midnight. Falstaff foi uma personagem muito amada pelo actor realizador, que nele via uma espécie de duplo, com as mesmas paixões, prazeres e apetites. -

{Dоwnlоаd/Rеаd PDF Bооk} Citizen Kane Ebook, Epub

CITIZEN KANE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Harlan Lebo | 368 pages | 01 May 2016 | Thomas Dunne Books | 9781250077530 | English | United States Citizen Kane () - IMDb Mankiewicz , who had been writing Mercury radio scripts. One of the long-standing controversies about Citizen Kane has been the authorship of the screenplay. In February Welles supplied Mankiewicz with pages of notes and put him under contract to write the first draft screenplay under the supervision of John Houseman , Welles's former partner in the Mercury Theatre. Welles later explained, "I left him on his own finally, because we'd started to waste too much time haggling. So, after mutual agreements on storyline and character, Mank went off with Houseman and did his version, while I stayed in Hollywood and wrote mine. The industry accused Welles of underplaying Mankiewicz's contribution to the script, but Welles countered the attacks by saying, "At the end, naturally, I was the one making the picture, after all—who had to make the decisions. I used what I wanted of Mank's and, rightly or wrongly, kept what I liked of my own. The terms of the contract stated that Mankiewicz was to receive no credit for his work, as he was hired as a script doctor. Mankiewicz also threatened to go to the Screen Writers Guild and claim full credit for writing the entire script by himself. After lodging a protest with the Screen Writers Guild, Mankiewicz withdrew it, then vacillated. The guild credit form listed Welles first, Mankiewicz second. Welles's assistant Richard Wilson said that the person who circled Mankiewicz's name in pencil, then drew an arrow that put it in first place, was Welles. -

A History of Production

A HISTORY OF PRODUCTION 2020-2021 2019-2020 2018-2019 Annie Stripped: Cry It Out, Ohio State The Humans 12 Angry Jurors Murders, The Empty Space Private Lies Avenue Q The Wolves The Good Person of Setzuan john proctor is the villain As It Is in Heaven Sweet Charity A Celebration of Women’s Voices in Musical Theatre 2017-2018 2016-2017 2015-2016 The Cradle Will Rock The Foreigner Reefer Madness Sense and Sensibility Upton Abbey Tartuffe The Women of Lockerbie A Piece of my Heart Expecting Isabel 9 to 5 Urinetown Hello, Dolly! 2014-2015 2013-2014 2012-2013 Working The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later The Miss Firecracker Contest Our Town The 25th Annual Putnam County The Drowsy Chaperone Machinal Spelling Bee Anna in the Tropics Guys and Dolls The Clean House She Stoops to Conquer The Lost Comedies of William Shakespeare 2011-2012 2010-2011 2009-2010 The Sweetest Swing in Baseball Biloxi Blues Antigone Little Shop of Horrors Grease Cabaret Picasso at the Lapin Agile Letters to Sala How I Learned to Drive Love’s Labour’s Lost It’s All Greek to Me Playhouse Creatures 2008-2009 2007-2008 2006-2007 Doubt Equus The Mousetrap They’re Playing Our Song Gypsy Annie Get Your Gun A Midsummer Night’s Dream The Importance of Being Earnest Rumors I Hate Hamlet Murder We Wrote Henry V 2005-2006 2004-2005 2003-2004 Starting Here, Starting Now Oscar and Felix Noises Off Pack of Lies Extremities 2 X Albee: “The Sandbox” and “The Zoo All My Sons Twelfth Night Story” Lend Me a Tenor A Day in Hollywood/A Night in the The Triumph of Love Ukraine Babes in Arms -

Reading in the Dark: Using Film As a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 456 446 CS 217 685 AUTHOR Golden, John TITLE Reading in the Dark: Using Film as a Tool in the English Classroom. INSTITUTION National Council of Teachers of English, Urbana, IL. ISBN ISBN-0-8141-3872-1 PUB DATE 2001-00-00 NOTE 199p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council of Teachers of English, 1111 W. Kenyon Road, Urbana, IL 61801-1096 (Stock No. 38721-1659: $19.95, members; $26.95, nonmembers). Tel: 800-369-6283 (Toll Free); Web site http://www.ncte.org. PUB TYPE Books (010) Guides Non-Classroom (055) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Classroom Techniques; *Critical Viewing; *English Instruction; *Film Study; *Films; High Schools; Instructional Effectiveness; Language Arts; *Reading Strategies; Units of Study IDENTIFIERS *Film Viewing; *Textual Analysis ABSTRACT To believe that students are not using reading and analytical skills when they watch or "read" a movie is to miss the power and complexities of film--and of students' viewing processes. This book encourages teachers to harness students' interest in film to help them engage critically with a range of media, including visual and printed texts. Toward this end, the book provides a practical guide to enabling teachers to ,feel comfortable and confident about using film in new and different ways. It addresses film as a compelling medium in itself by using examples from more than 30 films to explain key terminology and cinematic effects. And it then makes direct links between film and literary study by addressing "reading strategies" (e.g., predicting, responding, questioning, and storyboarding) and key aspects of "textual analysis" (e.g., characterization, point of view, irony, and connections between directorial and authorial choices) .The book concludes with classroom-tested suggestions for putting it all together in teaching units on 11 films ranging from "Elizabeth" to "Crooklyn" to "Smoke Signals." Some other films examined are "E.T.," "Life Is Beautiful," "Rocky," "The Lion King," and "Frankenstein." (Contains 35 figures. -

Film Reviews Interviews Video Interviews

berlinale 2019 EFM Coverage as of Feb 20, 2019 300 Photos published on facebook 34 videos published on youtube FILM REVIEWS AMAZING GRACE, A Long Delayed Aretha Franklin Film surfaces at Berlin '69 What she said: The Art of Pauline Kael review Leakage | Nasht by Suzan Iravanian (Forum): Berlinale Review The Golden Glove by Fatih Akin: Berlinale Review Sampled reviews of Jessica Forever A City Hunts for a Murderer, and a Forum film hunts for meaning Berlinale by Alex: Mid Point Festival Reviews MK2 is very proud from the reviews on the Varda doc The Ground beneath my Feet in review Sondre Fristad's First Feature The Writer at the Berlinale System Crasher in review: Amazing ! Forget about all other contenders Derek Jarman's THE GARDEN, starring Tilda Swinton, returns to Berlinale 28 years after its premiere DIE KINDER DER TOTEN - World Premiere and Q&A with Kelly Copper and Pavol Liska INTERVIEWS Xaver Böhm on O Beautiful Night: Interview at Berlinale 2019 Interview with Brazilian Director Marcus Ligocki at Berlinale Marie Kreuzer: The Ground beneath my feet The Writer: Interview with Sondre Fristad in Berlin Interview with Producer, Director Writer Stu Levy @ 2019 Berlinale Interview with Director Gustavo Steinberg for 'Tito and the Birds' (2018) Alexandr Gorchilin on his First Feature Acid VIDEO INTERVIEWS VIDEO: Dieter Kosslick recalls some nice moments on the red carpet VIDEO: Anthony Bregman describes IFP's programs suppporting independent film making VIDEO: IFP Anthony Bregman opening remarks on his producing experiences at Friday's -

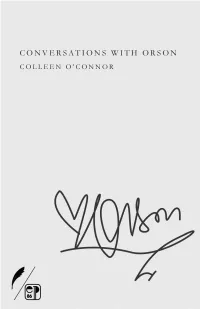

Oconnor Conversations Spread

CONVERSATIONS WITH ORSON COLLEEN O’CONNOR #86 ESSAY PRESS NEXT SERIES Authors in the Next series have received finalist Contents recognition for book-length manuscripts that we think deserve swift publication. We offer an excerpt from those manuscripts here. Series Editors Maria Anderson Introduction vii Andy Fitch by David Lazar Ellen Fogelman Aimee Harrison War of the Worlds 1 Courtney Mandryk Grover’s Mill, New Jersey, 1938 Victoria A. Sanz Travis A. Sharp The Third Man 6 Ryan Spooner Vienna, 1949 Alexandra Stanislaw Citizen Kane 11 Series Assistants Cristiana Baik Ryan Ikeda Xanadu, Florida, 1941 Christopher Liek Emily Pifer Touch of Evil 17 Randall Tyrone Mexico/U.S. Border, 1958 Cover Design Ryan Spooner F for Fake 22 Ibiza, Spain, 1975 Composition Aimee Harrison Acknowledgments & Notes 24 Author Bio 26 Introduction — David Lazar “Desire is an acquisition,” Colleen O’Connor writes in her unsettling series, Conversations with Orson. And much of desire is dark and escapable, the original noir of noir. The narrator is and isn’t O’Connor. Just as Orson is and isn’t Welles. Orson/O’Connor. O, the plasticity of persona. There is a perverse desire to be both known and unknown in these pieces, fragments of essay, prose poems, bad dreams. How to wrap around a signifier that big, that messy, spilling out so many shadows! Colleen O’Connor pierces her Orson Welles with pity and recognition. We imagine them on Corsica thanks to a time machine, her vivid imagination, and a kind of bad cinematic hangover. The hair of the dog is the deconstruction of the male gaze. -

An Educational Guide Filled with Youthful Bravado, Welles Is a Genius Who Is in Love with and Welles Began His Short-Lived Reign Over the World of Film

Welcome to StageDirect Continued from cover Woollcott and Thornton Wilder. He later became associated with StageDirect is dedicated to capturing top-quality live performance It’s now 1942 and the 27 year old Orson Welles is in Rio de Janeiro John Houseman, and together, they took New York theater by (primarily contemporary theater) on digital video. We know that there is on behalf of the State Department, making a goodwill film for the storm with their work for the Federal Theatre Project. In 1937 their tremendous work going on every day in small theaters all over the world. war effort. Still struggling to satisfy RKO with a final edit, Welles is production of The Cradle Will Rock led to controversy and they were This is entertainment that challenges, provokes, takes risks, explodes forced to entrust Ambersons to his editor, Robert Wise, and oversee fired. Soon after Houseman and Welles founded the Mercury Theater. conventions - because the actors, writers, and stage companies are not its completion from afar. The company soon made the leap from stage to radio. slaves to the Hollywood/Broadway formula machine. These productions It’s a hot, loud night in Rio as Orson Welles (actor: Marcus In 1938, the Mercury Theater’s War of the Worlds made appear for a few weeks, usually with little marketing, then they disappear. Wolland) settles in to relate to us his ‘memoir,’ summarizing the broadcast history when thousands of listeners mistakenly believed Unless you’re a real fanatic, you’ll miss even the top performances in your early years of his career in theater and radio. -

1 Orson Welles' Three Shakespeare Films: Macbeth, Othello, Chimes At

1 Orson Welles’ three Shakespeare films: Macbeth, Othello, Chimes at Midnight Macbeth To make any film, aware that there are plenty of people about who’d rather you weren’t doing so, and will be quite happy if you fail, must be a strain. To make films of Shakespeare plays under the same constraint requires a nature driven and thick-skinned above and beyond the normal, but it’s clear that Welles had it. His Macbeth was done cheaply in a studio in less than a month in 1948. His Othello was made over the years 1949-1952, on a variety of locations, and with huge gaps between shootings, as he sold himself as an actor to other film- makers so as to raise the money for the next sequence. I’m going to argue that the later movie shows evidence that he learned all kinds of lessons from the mistakes he made when shooting the first, and that there is a huge gain in quality as a consequence. Othello is a minor masterpiece: Macbeth is an almost unredeemed cock-up. We all know that the opening shot of Touch of Evil is a virtuoso piece of camerawork: a single unedited crane-shot lasting over three minutes. What is not often stressed is that there’s another continuous shot, less spectacular but no less well-crafted, in the middle of that film (it’s when the henchmen of Quinlan, the corrupt cop, plant evidence in the fall-guy’s hotel room). What is never mentioned is that there are two shots still longer in the middle of Macbeth . -

Δημοτικός Κινηματογράφος ΚΗΠΟΣ Municipal Cinema KIPOS Πρόγραμμα Προβολών Screenings

Δημοτικός Κινηματογράφος ΚΗΠΟΣ Municipal Cinema KIPOS Πρόγραμμα προβολών Screenings schedule 2019 κινηματογράφου, πέρασαν από εδώ κατά σειρά Μανωλικάκηδες, Σαββάκηδες, Σπανδάγοι, Χατζηδάκηδες, Βενιανάκηδες, Πολάκηδες και Μπονάνοι και μέχρι την εποχή των Σπανδάγων, οπότε ο κινηματογράφος από δυτικά μεταφέρθηκε στη νέα του θέση κάτω από το Ρολόι και από το προαναφερθέν πρωτόγονο «Σινέ Ασετιλίνη» έγινε ηλεκτροκίνητος, απέκτησε πανοραμική οθόνη και μάλιστα στη συνέχεια, όταν έγινε και σινεμασκόπ, πήρε και το όνομα «Τιτάνια»! Στις 6 Μαρτίου 1980, το Δημοτικό Συμβούλιο Χανίων με την με αρθ. 13 απόφασή του, δημιουργεί τον Δημοτικό Κιν/φο «ΚΗΠΟΣ» -τον πρώτο στη χώρα μας. Η απόφαση δεν ήταν εύκολη. Κάποιοι δίσταζαν, άλλοι ανησυχούσαν. Ήταν η πρώτη φορά στην ιστορία του, που ο Δήμος θα έκανε τον επιχειρηματία, χωρίς μάλιστα να προβλέπεται από κανένα θεσμικό πλαίσιο (ο Νόμος για τις Δημοτικές Επιχειρήσεις ήρθε πολλά χρόνια αργότερα). Την επιτροπή διεύθυνσης του κινηματογράφου θα αποτελούσαν ομάδα δημοτικών συμβούλων και μέλη της Κινηματογραφικής Λέσχης, που θα είχαν και την επιμέλεια του προγράμματος. Σε χρόνο ρεκόρ ο χώρος του κινηματογράφου ετοιμάστηκε, αγοράστηκαν καθίσματα, μηχανή κλπ και στις 30 Μάη 1980 η πρεμιέρα: Το Αυγό του Φιδιού του Μπέργκμαν. Ένα πείραμα άρχιζε.... Όλα αυτά τα χρόνια ο ΚΗΠΟΣ παρέμεινε σταθερά πόλος έλξης των κινηματογραφόφιλων, τόσο των Χανιωτών όσο και των επισκεπτών της πόλης μας. Ο ΚΗΠΟΣ συνεχίζει το ταξίδι του στις εικόνες και τους ήχους, μοναδικό παράδειγμα πολιτισμού και ψυχαγωγίας. Δημοτικός Κινηματογράφος ΚΗΠΟΣ Μοναδικό παράδειγμα πολιτισμού και ψυχαγωγίας Στο Δημοτικό Κήπο των Χανίων βρίσκεται ο δημοτικός θερινός κινηματογράφος της πόλης. Ο ίδιος ο χώρος του κινηματογράφου είναι απόλυτα εναρμονισμένος με το καταπράσινο φυσικό περιβάλλον του Κήπου, ενώ πρόσθετη μεγαλοπρέπεια δίνει το πέτρινο ρολόι που κατασκευάστηκε το 1913. -

Kurt Weill Newsletter

KURT WEILL NEWSLETTER Volume8,Number 1 Spring1990 Kurt Weill IN THIS ISSUE 1990 KURT W EILL FESTIVAL IN NORTH RHINE WESTPHALIA 7 (Re-) Unification? by Christopher Hailey 9 Der Kuhhandel by Michael Morley 11 Niederrheinische Chorgemeinschaft review by Jurgen Thym 12 KURT-WED.,L-FESTIVAL Robert-Schumann-Hochschule concert review by Gunther Diehl 13 Teacher Workshops in Heek 13 Exhibitions 14 Press Clippings 15 COLUMNS News in Brief 2 Letters to the Editor 5 New Publications 16 Selected Performances 27 BooKs Studien zur Berliner Musikgeschichte edited by Traude Ebert-Obermeier 18 PERFORMANCES Street Scene at the English National Opera 20 Sinfonia San Francisco 21 Lady in the Dark at Light Opera Works 22 \-.il!N'! ~pt.-a.hl~ll~ail Seven Deadly Sins atTheJuilliard School 23 l,,lllll•~-'ll~,l......,._1,_.. ,,.,,..._,'ftt~nt '\1l~.11,....,..'(11tt lt11.-.....t.., 3-ld•llrilrll ..-•1fw......... Ji,d~(ontllldilt , l""NNW"a.....iK,..1 11.-fw-,.,,,...,t ~,\ Downtown Chamber and Opera Players 24 RECORDINGS Die Dreigroschenoper on Decca/London 25 7 North Rhine Westphalia Christopher Hailey analyzes th e significance of the festival and symposium, Mich ael Morley critiques Der Kuhha ndel, J u rgen Thym an d Gunt h er Diehl report on concerts. Also news articles, p hotos, and p ress clippings. 2 The American Musical Theater Festival opens the first professional revival of Love Life on 10 June at the Walnut Theatre in Philadelphia. The show runs through 24 June, with Almeida Festival in London performances at 8:00 PM Tuesday-Saturday and matinees on 13, 16, 20, and 24 June at 2:00 PM.