Writing Systems and Literacy Methods: Schooling Models in Western Curricula from the Seventeen to the Twentieth Century Anne-Marie Chartier

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Functional Literacy and Numeracy

MUVA: inquérito de literacia e numeracia funcional Conteúdo Motivation: Why did we do this work? Objectives: What did we try to measure and why does it matter? Methodology: Survey set-up, instruments, and levels of functional literacy and numeracy. Results: What are the levels of literacy and numeracy among the youth in Maputo and Beira? How are these related to gender, schooling, and economic activities? Implications Motivation: Why did we do this survey? MUVA Urban Youth Survey gave us data on young people’s “level of education” (highest class completed) However, we know that the level of education does not directly translate into skills and knowledge Highest class completed is not a good proxy for what young people actually can do at the workplace Experience from our projects show that even young people from 10th and 12th grade struggle with basic everyday workplace reading, writing, and numeracy tasks. Objective: What did we try to measure? Hence, we decided to go back to a sample of participants in our original MUVA Youth Survey to measure their ‘workplace literacy and numeracy’ We defined this as “a level of reading, writing and calculation skills sufficient to function in the particular community in which an individual lives and to effectively execute the tasks required at their place of work.” (Borrowed from UNICEF) This means we are interested in skills like: ability to comprehend, use, produce, and record information and calculations needed to get a job done right and on time. These are not the necessarily the same skills that are needed to get good grades in school. -

Literacy in India: the Gender and Age Dimension

OCTOBER 2019 ISSUE NO. 322 Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension TANUSHREE CHANDRA ABSTRACT This brief examines the literacy landscape in India between 1987 and 2017, focusing on the gender gap in four age cohorts: children, youth, working-age adults, and the elderly. It finds that the gender gap in literacy has shrunk substantially for children and youth, but the gap for older adults and the elderly has seen little improvement. A state-level analysis of the gap reveals the same trend for most Indian states. The brief offers recommendations such as launching adult literacy programmes linked with skill development and vocational training, offering incentives such as employment and micro-credit, and leveraging technology such as mobile-learning to bolster adult education, especially for females. It underlines the importance of community participation for the success of these initiatives. Attribution: Tanushree Chandra, “Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension”, ORF Issue Brief No. 322, October 2019, Observer Research Foundation. Observer Research Foundation (ORF) is a public policy think tank that aims to influence the formulation of policies for building a strong and prosperous India. ORF pursues these goals by providing informed analyses and in-depth research, and organising events that serve as platforms for stimulating and productive discussions. ISBN 978-93-89622-04-1 © 2019 Observer Research Foundation. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, copied, archived, retained or transmitted through print, speech or electronic media without prior written approval from ORF. Literacy in India: The Gender and Age Dimension INTRODUCTION “neither in terms of absolute levels of literacy nor distributive justice, i.e., reduction in gender Literacy is one of the most essential indicators and caste disparities, does per capita income of the quality of a country’s human capital. -

A Nation at Risk

A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform A Report to the Nation and the Secretary of Education United States Department of Education by The National Commission on Excellence in Education April 1983 April 26, 1983 Honorable T. H. Bell Secretary of Education U.S. Department of Education Washington, D.C. 20202 Dear Mr. Secretary: On August 26, 1981, you created the National Commission on Excellence in Education and directed it to present a report on the quality of education in America to you and to the American people by April of 1983. It has been my privilege to chair this endeavor and on behalf of the members of the Commission it is my pleasure to transmit this report, A Nation at Risk: The Imperative for Educational Reform. Our purpose has been to help define the problems afflicting American education and to provide solutions, not search for scapegoats. We addressed the main issues as we saw them, but have not attempted to treat the subordinate matters in any detail. We were forthright in our discussions and have been candid in our report regarding both the strengths and weaknesses of American education. The Commission deeply believes that the problems we have discerned in American education can be both understood and corrected if the people of our country, together with those who have public responsibility in the matter, care enough and are courageous enough to do what is required. Each member of the Commission appreciates your leadership in having asked this diverse group of persons to examine one of the central issues which will define our Nation's future. -

A Review About Functional Illiteracy: Definition, Cognitive, Linguistic, And

fpsyg-07-01617 November 8, 2016 Time: 17:17 # 1 View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Frontiers - Publisher Connector REVIEW published: 10 November 2016 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01617 A Review about Functional Illiteracy: Definition, Cognitive, Linguistic, and Numerical Aspects Réka Vágvölgyi1*, Andra Coldea2, Thomas Dresler1,3, Josef Schrader1,4 and Hans-Christoph Nuerk1,5,6* 1 LEAD Graduate School & Research Network, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 2 School of Psychology, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland, 3 Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 4 German Institute for Adult Education – Leibniz Centre for Lifelong Learning, Bonn, Germany, 5 Department of Psychology, University of Tuebingen, Tuebingen, Germany, 6 Knowledge Media Research Center – Leibniz Institut für Wissensmedien, Tuebingen, Germany Formally, availability of education for children has increased around the world over the last decades. However, despite having a successful formal education career, adults can become functional illiterates. Functional illiteracy means that a person cannot use Edited by: reading, writing, and calculation skills for his/her own and the community’s development. Bert De Smedt, KU Leuven, Belgium Functional illiteracy has considerable negative effects not only on personal development, Reviewed by: but also in economic and social terms. Although functional illiteracy has been highly Jascha Ruesseler, publicized in mass media in the recent years, there is limited scientific knowledge University of Bamberg, Germany Sarit Ashkenazi, about the people termed functional illiterates; definition, assessment, and differential Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Israel diagnoses with respect to related numerical and linguistic impairments are rarely *Correspondence: studied and controversial. -

Literacy UN Acked: What DO WE MEAN by Literacy?

Memo 4 | Fall 2012 LEAD FOR LITERACY MEMO Providing guidance for leaders dedicated to children's literacy development, birth to age 9 L U: W D W M L? The Issue: To make decisions that have a positive What Competencies Does a Reader Need to impact on children’s literacy outcomes, leaders need a Make Sense of This Passage? keen understanding of literacy itself. But literacy is a complex concept and there are many key HIGH-SPEED TRAINS* service that moved at misunderstandings about what, exactly, literacy is. A type of high-speed a speed of one train was first hundred miles per Unpacking Literacy Competencies hour. Today, similar In this memo we focus specifically on two broad introduced in Japan about forty years ago. Japanese trains are categories of literacy competencies: skills‐based even faster, traveling The train was low to competencies and knowledge‐based competencies. at speeds of almost the ground, and its two hundred miles nose looked somewhat per hour. There are like the nose of a jet. Literacy many reasons that These trains provided high-speed trains are Reading, Wring, Listening & Speaking the first passenger popular. * Passage adapted from Good & Kaminski (2007) Skills Knowledge Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, 6th ed. ‐ Concepts about print ‐ Concepts about the ‐ The ability to hear & world Map sounds onto letters (e.g., /s/ /p/ /ee/ /d/) work with spoken sounds ‐ The ability to and blend these to form a word (speed) ‐ Alphabet knowledge understand & express Based ‐ Word reading complex ideas ‐ Recognize -

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet

Dyslexia and Structured Literacy Fact Sheet Written by Belinda Dekker Dyslexia Support Australia https://dekkerdyslexia.wordpress.com/ Structured Literacy • Structured literacy is a scientifically researched based approach to the teaching of reading. Structured literacy can be in the form of teachers trained in the use of structured literacy methodologies and programs that adhere to the fundamental and essential components of structured literacy. • Structure means that there is a step by step clearly defined systematic process to the teaching of reading. Including a set procedure for introducing, reviewing and practicing essential concepts. Concepts have a clearly defined sequence from simple to more complex. Each new concept builds upon previously introduced concepts. • Knowledge is cumulative and the program or teacher will use continuous assessment to guide a student’s progression to the next clearly defined step in the program. An important fundamental component is the automaticity of a concept before progression. • Skills are explicitly or directly taught to the student with clear explanations, examples and modelling of concepts. ‘The term “Structured Literacy” is not designed to replace Orton Gillingham, Multi-Sensory or other terms in common use. It is an umbrella term designed to describe all of the programs that teach reading in essentially the same way'. Hal Malchow. President, International Dyslexia Association A Position Statement on Approaches to Reading Instruction Supported by Learning Difficulties Australia "LDA supports approaches to reading instruction that adopt an explicit structured approach to the teaching of reading and are consistent with the scientific evidence as to how children learn to read and how best to teach them. -

2020-08-09 Edition

HAMILTON COUNTY Hamilton County’s Hometown Newspaper www.ReadTheReporter.com REPORTER Facebook.com/HamiltonCountyReporter TodAy’S Weather Sunday, Aug. 9, 2020 Today: Partly sunny. Isolated shower or storm possible. Arcadia | Atlanta | Cicero | Sheridan Tonight: Partly cloudy. Spotty showers and storms. Carmel | Fishers | Noblesville | Westfield NEWS GATHERING Like & PARTNER Follow us! HIGH: 86 LOW: 69 Just my opinion Community First Bank gives "I hope you don't COLUMNIST take this personally." Well how else am I supposed to take it? $2,500 check to Noblesville Elks Most people do not The REPORTER intend to hurt us. The 35th annual Steve Renner Golf With that being Outing for Cancer Research could not be said, there are those held due to current public safety guide- who seem to have a lines and health concerns of members and knack for telling us JANET HART LEONARD participants. what they think and From the Heart However, Community First Bank of not in a good way. Indiana still remained committed to the It's like they should be saying, "I'm not Noblesville Elks Lodge by presenting a sorry for telling you this. You need to know $2,500 check on Thursday in support of the ... blah blah blah." Then they proceed to Elks and its dedication to the Noblesville leave a not-so-nice plate of doo doo in our community for cancer research. lap. They then walk away feeling like they The Elks' State Major Project fights the have done their duty. Malarky. various dreaded cancer diseases. Indiana How do we deal with it? has two major cancer research facilities, In the past I would mostly smile and with one located at Purdue University's Photo provided say, "Oh it's OK." But it wasn't. -

Orton-Gillingham Or Multisensory Structured Language Approaches

JUST THE FACTS... Information provided by The International Dyslexia Association® ORTON-GILLINGHAM-BASED AND/OR MULTISENSORY STRUCTURED LANGUAGE APPROACHES The principles of instruction and content of a Syntax: Syntax is the set of principles that dictate the multisensory structured language program are essential sequence and function of words in a sentence in order for effective teaching methodologies. The International to convey meaning. This includes grammar, sentence Dyslexia Association (IDA) actively promotes effective variation, and the mechanics of language. teaching approaches and related clinical educational Semantics: Semantics is that aspect of language intervention strategies for dyslexics. concerned with meaning. The curriculum (from the beginning) must include instruction in the CONTENT: What Is Taught comprehension of written language. Phonology and Phonological Awareness: Phonology is the study of sounds and how they work within their environment. A phoneme is the smallest unit of sound PRINCIPLES OF INSTRUCTION: How It Is Taught in a given language that can be recognized as being Simultaneous, Multisensory (VAKT): Teaching is distinct from other sounds in the language. done using all learning pathways in the brain Phonological awareness is the understanding of the (visual/auditory, kinesthetic-tactile) simultaneously in internal linguistic structure of words. An important order to enhance memory and learning. aspect of phonological awareness is phonemic awareness or the ability to segment words into their Systematic and Cumulative: Multisensory language component sounds. instruction requires that the organization of material follows the logical order of the language. The Sound-Symbol Association: This is the knowledge of sequence must begin with the easiest and most basic the various sounds in the English language and their elements and progress methodically to more difficult correspondence to the letters and combinations of material. -

About Fforum

Contents About fforum ..................... 102 Television Viewing Experience : Text and Context in the Development of About fforum: Essays on Theory and Writing Skills Practice in the Teaching of Writing .. 103 Jean Long....................... 165 About this IsSue .................. 104 Evaluating Writing in an Academic Setting The Social Context of Literacy Michael Clark................... 170 Jay L. Robinson................... 105 Practicing Research by Researching The Literacy Crisis: A Challenge How? Practice William E. Coles, Jr.............. 114 Loren S. Barritt................ 187 Why We Teach Writing in the First Place A Comprehensive Literacy Program: Toby Fulwiler..................... 122 The English Composition Board patricia L. Stock............... 192 Metatheories of Rhetoric: Past Pipers Janice Lauer...................... 134 Select Bibliography Robert L. Root.................. 201 Rhetoric and the Teaching of Writing Cy ~noblauch...................... 137 Resources in the Teaching of Composition Science Writing and Literacy Robert L. Root.................. 216 Grace Rueter and Thomas M. Dunn... 141 d Language, Literature,and the Humanistic Tradition: Necessities in the Education of the Physician About fforum John H. Siegel, M.D............... 148 This issue of fforum is the last reqularly ~irstSilence, Then Paper scheduled number of the newsletter which - the English Composition Board will pub- Donald M. Murray.................. 155 lish. As you may imagine, 1 write this news to you with mixed feelings. On the Quiet, Paper, Madness: Place for A one hand, the newsletter has served the Writing to Reach To John Warnock...................... 161 purpose for which it was conceived at the first in a series of annual workshops for teachers in schools, colleges, and universities in the state of Michigan: Published twice annually by Winter, 1983 It has provided a vehicle for continuing The English Composition Board Vol. -

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program

Structured Literacy and the SIPPS® Program The International Dyslexia Association identifies Structured Literacy as an effective instructional approach for meeting the needs of students who struggle with learning to read. Structured Literacy utilizes systematic, explicit instruction to teach decoding skills including phonology, sound-symbol association, syllable types, morphology, syntax, and semantics. Structured Literacy instruction has been around for over a century and is sometimes referred to as systematic reading instruction, phonics-based reading instruction, the Orton-Gillingham Approach, or synthetic phonics, among other names. The SIPPS (Systematic Instruction in Phonological Awareness, Phonics, and Sight Words) program, developed by Dr. John Shefelbine, is a multilevel program that develops the word-recognition strategies and skills that enable students to become independent and confident readers and writers. Dr. Shefelbine’s research emphasizes systematic instruction, and in many ways parallels the Orton-Gillingham Approach. Structured Literacy The table below notes the elements of Structured Literacy aligned to the SIPPS program. Elements of Structured Literacy SIPPS Phonology Defined as the study of sound structure of spoken Phonological awareness activities appear in every words; includes rhyming, counting words in lesson in SIPPS Beginning, Extension, and Plus. spoken sentences, clapping syllables in spoken These activities begin with segmenting and words, and phonemic awareness (manipulation of blending, include rhyme, and increase in complexity sounds). to dropping and substituting phonemes. Sound-Symbol Association Defined as connecting sounds to print, including Spelling-sounds are explicitly taught throughout the blending and segmenting. This should occur two program. Sounds are taught in order of utility, which ways: visual to auditory (reading) and auditory to allows students to quickly begin to read connected visual (spelling). -

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: the Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C

Evidence Based Practice: Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy Francis, T., & Beck, C. (2018). Visual Motor Integration for Building Literacy: The Role of Occupational Therapy. OT Practice 23(15), 14–18. The Research: Occupational therapy interventions for visual processing skills were found to positively affect academic achievement and social participation. Key elements of intervention activities needed for progress include: fine motor activities, copying skills, gross motor activities, and a high level of cognitive interaction with completing activities. What is it? Visual information processing skills refers to “a group of visual cognitive skills used for extracting and organizing visual information from the environment and integrating this information with other sensory modalities and higher cognitive functions”. Visual information processing skills are divided into three components: visual spatial, visual analysis, and visual motor. Visual motor integration skills (i.e. eye-hand coordination) are related to an individual’s ability to combine visual information processing skills with fine motor or gross motor movement. Studies have found that visual motor integration is a component of reading skills in children in elementary school Specific Combination of Intervention Strategies Found to be Successful Fine motor activities ● Intervention activities: Manipulating small items (e.g., beads, coins); opening the thumb web space, separating the two sides of the hand; practicing finger isolation; -

Phonological Awareness Visual Perception Sequencing Memory

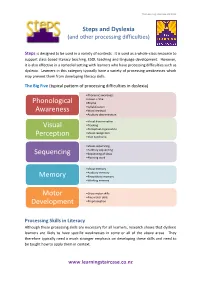

The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 Steps and Dyslexia (and other processing difficulties) Steps is designed to be used in a variety of contexts. It is used as a whole-class resource to support class-based literacy teaching, ESOL teaching and language development. However, it is also effective in a remedial setting with learners who have processing difficulties such as dyslexia. Learners in this category typically have a variety of processing weaknesses which may prevent them from developing literacy skills. The Big Five (typical pattern of processing difficulties in dyslexia) •Phonemic awareness •Onset + rime Phonological •Rhyme •Syllabification Awareness •Word retrieval •Auditory discrimination •Visual discrimination Visual •Tracking •Perceptual organisation •Visual recognition Perception •Irlen Syndrome •Visual sequencing •Auditory sequencing Sequencing •Sequencing of ideas •Planning work •Visual memory •Auditory memory Memory •Kinaesthetic memory •Working memory Motor •Gross motor skills •Fine motor skills Development •Proprioception Processing Skills in Literacy Although these processing skills are necessary for all learners, research shows that dyslexic learners are likely to have specific weaknesses in some or all of the above areas. They therefore typically need a much stronger emphasis on developing these skills and need to be taught how to apply them in context. www.learningstaircase.co.nz The Learning Staircase Ltd 2012 However, there are further aspects which are important, particularly for learners with literacy difficulties, such as dyslexia. These learners often need significantly more reinforcement. Research shows that a non-dyslexic learner needs typically between 4 – 10 exposures to a word to fix it in long-term memory. A dyslexic learner, on the other hand, can need 500 – 1300 exposures to the same word.