An Exploration of Underplayed Violin Concertos Appropriate for Intermediate and Advanced Students Heather Ann Wolters Hart

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Program Notes by Eric Bromberger

PROGRAM NOTES BY ERIC BROMBERGER Concerto for Four Violins in B Minor, Op. 3, No. 10, RV 580 ANTONIO VIVALDI b. March 4, 1678; Venice, Italy d. July 27 or 28, 1741; Venice, Italy Composed 1711 Performance Time 10 minutes In the early years of the eighteenth century, Vivaldi held the rather modest position of director of a conservatory for homeless girls in Venice, but his compositions were carrying his name throughout Europe. In 1711, he published a collection of twelve violin concertos under the title L’Estro armonico, translated variously as “The Spirit of Harmony” or “Harmonious Inspiration.” Significantly, Vivaldi chose to have this set published in Amsterdam, and for two good reasons: printing techniques there were superior to any available in Italy and, perhaps more important, his music was extremely popular in northern Europe. Each of the concertos of L’Estro armonico is a concerto grosso, in which one or more violin soloists is set against a main body of strings and harpsichord continuo. The intent in these concertos is not so much virtuosic display (though they are difficult enough, certainly) as it is in making contrast between the sound of the solo instruments and the main body of strings. The twelve concertos of L’Estro armonico quickly became popular and influential in northern Europe. Bach knew this music very well, and – if imitation is the sincerest form of flattery – paid Vivaldi the immense compliment of transcribing six of these concertos for different instruments and using them as his own (a practice that would be highly questionable today but which was viewed more generously three centuries ago): the present Concerto for Four Violins in B Minor became Bach’s Concerto for Four Claviers in A Minor, BWV 1065. -

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition

The String Quartets of George Onslow First Edition All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Edition Silvertrust a division of Silvertrust and Company Edition Silvertrust 601 Timber Trail Riverwoods, Illinois 60015 USA Website: www.editionsilvertrust.com For Loren, Skyler and Joyce—Onslow Fans All © 2005 R.H.R. Silvertrust 1 Table of Contents Introduction & Acknowledgements ...................................................................................................................3 The Early Years 1784-1805 ...............................................................................................................................5 String Quartet Nos.1-3 .......................................................................................................................................6 The Years between 1806-1813 ..........................................................................................................................10 String Quartet Nos.4-6 .......................................................................................................................................12 String Quartet Nos. 7-9 ......................................................................................................................................15 String Quartet Nos.10-12 ...................................................................................................................................19 The Years from 1813-1822 ...............................................................................................................................22 -

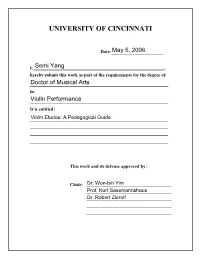

University of Cincinnati

UNIVERSITY OF CINCINNATI Date:___________________ I, _________________________________________________________, hereby submit this work as part of the requirements for the degree of: in: It is entitled: This work and its defense approved by: Chair: _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ _______________________________ VIOLIN ETUDES: A PEDAGOGICAL GUIDE A document submitted to the Division of Research and Advanced Studies of the University of Cincinnati in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS in the Performance Studies Division of the College-Conservatory of Music 2006 by Semi Yang [email protected] B.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1995 M.M., Queensland Conservatorium of Music, Griffith University, Australia, 1999 Advisor: Dr. Won-bin Yim Reader: Prof. Kurt Sassmannshaus Reader: Dr. Robert Zierolf ABSTRACT Studying etudes is one of the most essential parts of learning a specific instrument. A violinist without a strong technical background meets many obstacles performing standard violin literature. This document provides detailed guidelines on how to practice selected etudes effectively from a pedagogical perspective, rather than a historical or analytical view. The criteria for selecting the individual etudes are for the goal of accomplishing certain technical aspects and how widely they are used in teaching; this is based partly on my experience and background. The body of the document is in three parts. The first consists of definitions, historical background, and introduces different of kinds of etudes. The second part describes etudes for strengthening technical aspects of violin playing with etudes by Rodolphe Kreutzer, Pierre Rode, and Jakob Dont. The third part explores concert etudes by Wieniawski and Paganini. -

103 the Music Library of the Warsaw Theatre in The

A. ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA, MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW..., ARMUD6 47/1-2 (2016) 103-116 103 THE MUSIC LIBRARY OF THE WARSAW THEATRE IN THE YEARS 1788 AND 1797: AN EXPRESSION OF THE MIGRATION OF EUROPEAN REPERTOIRE ALINA ŻÓRAWSKA-WITKOWSKA UDK / UDC: 78.089.62”17”WARSAW University of Warsaw, Institute of Musicology, Izvorni znanstveni rad / Research Paper ul. Krakowskie Przedmieście 32, Primljeno / Received: 31. 8. 2016. 00-325 WARSAW, Poland Prihvaćeno / Accepted: 29. 9. 2016. Abstract In the Polish–Lithuanian Common- number of works is impressive: it included 245 wealth’s fi rst public theatre, operating in War- staged Italian, French, German, and Polish saw during the reign of Stanislaus Augustus operas and a further 61 operas listed in the cata- Poniatowski, numerous stage works were logues, as well as 106 documented ballets and perform ed in the years 1765-1767 and 1774-1794: another 47 catalogued ones. Amongst operas, Italian, French, German, and Polish operas as Italian ones were most popular with 102 docu- well ballets, while public concerts, organised at mented and 20 archived titles (totalling 122 the Warsaw theatre from the mid-1770s, featured works), followed by Polish (including transla- dozens of instrumental works including sym- tions of foreign works) with 58 and 1 titles phonies, overtures, concertos, variations as well respectively; French with 44 and 34 (totalling 78 as vocal-instrumental works - oratorios, opera compositions), and German operas with 41 and arias and ensembles, cantatas, and so forth. The 6 works, respectively. author analyses the manuscript catalogues of those scores (sheet music did not survive) held Keywords: music library, Warsaw, 18th at the Archiwum Główne Akt Dawnych in War- century, Stanislaus Augustus Poniatowski, saw (Pl-Wagad), in the Archive of Prince Joseph musical repertoire, musical theatre, music mi- Poniatowski and Maria Teresa Tyszkiewicz- gration Poniatowska. -

Franco-Belgian Violin School: on the Rela- Tionship Between Violin Pedagogy and Compositional Practice Convegno Festival Paganiniano Di Carro 2012

5 il convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Convegno Società dei Concerti onlus 6 La Spezia Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini Lucca in collaborazione con Palazzetto Bru Zane Centre de Musique Romantique Française Venezia Musicalword.it CAMeC Centro Arte Moderna e Contemporanea Piazza Cesare Battisti 1 Comitato scientifico: Andrea Barizza, La Spezia Alexandre Dratwicki, Venezia Lorenzo Frassà, Lucca Roberto Illiano, Lucca / La Spezia Fulvia Morabito, Lucca Renato Ricco, Salerno Massimiliano Sala, Pistoia Renata Suchowiejko, Cracovia Convegno Festival Paganiniano di Carro 2012 Programma Lunedì 9 LUGLIO 10.00-10.30: Registrazione e accoglienza 10.30-11.00: Apertura dei lavori • Roberto Illiano (Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini / Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Francesco Masinelli (Presidente Società dei Concerti della Spezia) • Massimiliano Sala (Presidente Centro Studi Opera Omnia Luigi Boccherini, Lucca) • Étienne Jardin (Coordinatore scientifico Palazzetto Bru Zane, Venezia) • Cinzia Aloisini (Presidente Istituzione Servizi Culturali, Comune della Spezia) • Paola Sisti (Assessore alla Cultura, Provincia della Spezia) 10.30-11.30 Session 1 Nicolò Paganini e la scuola franco-belga presiede: Roberto Illiano 7 • Renato Ricco (Salerno): Virtuosismo e rivoluzione: Alexandre Boucher • Rohan H. Stewart-MacDonald (Leominster, UK): Approaches to the Orchestra in Paganini’s Violin Concertos • Danilo Prefumo (Milano): L’infuenza dei Concerti di Viotti, Rode e Kreutzer sui Con- certi per violino e orchestra di Nicolò Paganini -

My Musical Lineage Since the 1600S

Paris Smaragdis My musical lineage Richard Boulanger since the 1600s Barry Vercoe Names in bold are people you should recognize from music history class if you were not asleep. Malcolm Peyton Hugo Norden Joji Yuasa Alan Black Bernard Rands Jack Jarrett Roger Reynolds Irving Fine Edward Cone Edward Steuerman Wolfgang Fortner Felix Winternitz Sebastian Matthews Howard Thatcher Hugo Kontschak Michael Czajkowski Pierre Boulez Luciano Berio Bruno Maderna Boris Blacher Erich Peter Tibor Kozma Bernhard Heiden Aaron Copland Walter Piston Ross Lee Finney Jr Leo Sowerby Bernard Wagenaar René Leibowitz Vincent Persichetti Andrée Vaurabourg Olivier Messiaen Giulio Cesare Paribeni Giorgio Federico Ghedini Luigi Dallapiccola Hermann Scherchen Alessandro Bustini Antonio Guarnieri Gian Francesco Malipiero Friedrich Ernst Koch Paul Hindemith Sergei Koussevitzky Circa 20th century Leopold Wolfsohn Rubin Goldmark Archibald Davinson Clifford Heilman Edward Ballantine George Enescu Harris Shaw Edward Burlingame Hill Roger Sessions Nadia Boulanger Johan Wagenaar Maurice Ravel Anton Webern Paul Dukas Alban Berg Fritz Reiner Darius Milhaud Olga Samaroff Marcel Dupré Ernesto Consolo Vito Frazzi Marco Enrico Bossi Antonio Smareglia Arnold Mendelssohn Bernhard Sekles Maurice Emmanuel Antonín Dvořák Arthur Nikisch Robert Fuchs Sigismond Bachrich Jules Massenet Margaret Ruthven Lang Frederick Field Bullard George Elbridge Whiting Horatio Parker Ernest Bloch Raissa Myshetskaya Paul Vidal Gabriel Fauré André Gédalge Arnold Schoenberg Théodore Dubois Béla Bartók Vincent -

Violin Repertoire List

Violin Repertoire List In reverse order of difficulty (beginner books at top). Please send suggestions / additions to [email protected]. Version 1.1, updated 27 Aug 2015 List A: (Pieces in 1st position & basic notation) Fiddle Time Starters Fiddle Time Joggers Fiddle Time Runners Fiddle Time Sprinters The ABCs of Violin Musicland Violin Books Musicland Lollipop Man (Violin Duets) Abracadabra - Book 1 Suzuki Book 1 ABRSM Grade Book 1 VIolinSchool Editions: Popular Tunes in First Position ● Twinkle Twinkle Little Star ● London Bridge is Falling Down ● Frère Jacques ● When the Saints Go Marching In ● Happy Birthday to You ● What Shall We Do With the Drunken Sailor ● Ode to Joy ● Largo from The New World ● Long Long Ago ● Old MacDonald Had a Farm ● Pop! Goes the Weasel ● Row Row Row Your Boat ● Greensleeves ● The Irish Washerwoman ● Yankee Doodle Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 1 2 Step by Step Violin Play Violin Today String Builder Violin Book One (Samuel Applebaum) A Tune a Day I Can Read Music Easy Classical Violin Solos Violin for Dummies The Essential String Method (Sheila Nelson) Robert Pracht, Album of Easy Pieces, Op. 12 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 1 Waggon Wheels Superstudies (Mary Cohen) The Classical Experience Suzuki Book 2 Stanley Fletcher, New Tunes for Strings, Book 2 Doflein, Violin Method, Book 2 Alfred Moffat, Old Masters for Young Players D. Kabalevsky, Album Pieces for 1 and 2 Violins and Piano *************************************** List B: (Pieces in multiple positions and varieties of bow strokes) Level 1: Tomaso Albinoni Adagio in G minor Johann Sebastian Bach: Air on the G string Bach Gavotte in D (Suzuki Book 3) Bach Gavotte in G minor (Suzuki Book 3) Béla Bartók: 44 Duos for two violins Karl Bohm www.ViolinSchool.org | [email protected] | +44 (0) 20 3051 0080 3 Perpetual Motion Frédéric Chopin Nocturne in C sharp minor (arranged) Charles Dancla 12 Easy Fantasies, Op.86 Antonín Dvořák Humoresque King Henry VIII Pastime with Good Company (ABRSM, Grade 3) Fritz Kreisler: Berceuse Romantique, Op. -

Locatelli, Campagnoli, Ernst: Three Composers Under Paganini's Shadow

Fine Arts International Journal Srinakharinwirot University Vol. 15 No. 1 January - June 2011 Violin Recital The Unknown Violin Virtuoso - Locatelli, Campagnoli, Ernst: three composers under Paganini’s shadow. Mathias Boegner Department of Western Music Faculty of Fine Arts, Srinakharinwirot University, Thailand Corresponding author: [email protected], [email protected] Introduction In modern violin pedagogy we are aware Recently I followed two recommendations of skills and achievements from a few hundred from teachers and colleagues: From the famous years – nevertheless, various features are more pedagogue Prof. Max Rostal in Switzerland, well-known or famous than others, regardless to practice the Divertimenti by Campagnoli, their actual importance and impact. With all to improve safer intonation; and from my Italian respect to our great and unique icon Paganini, colleague Prof. Enzo Porta, to look for the some insight has been ascribed to his personality Caprices by Locatelli, in search for the so-called while in fact some of his colleagues found those “Labyrinth” in David Oistrakh’s performance. roots: Pietro Locatelli, one of the three violinist- My third third issue is the practicing of the works composers focused on here, has included the by Ernst, for climbing and challenging the violin complete demands of Paganini’s Caprices op.1 skills. in his own Caprices op. 3, long before Paganini 2 Fine Arts International Journal, Srinakharinwirot University was born. This concludes that the modernization II) His works and style of the violin building and the Tourte bow at III) The “Art of the Violin”, 24 Caprices Paganini’s time basically did not have to do with op. -

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED the CRITICAL RECEPTION of INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY in EUROPE, C. 1815 A

THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 A Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Cornell University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy by Zarko Cvejic August 2011 © 2011 Zarko Cvejic THE VIRTUOSO UNDER SUBJECTION: HOW GERMAN IDEALISM SHAPED THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF INSTRUMENTAL VIRTUOSITY IN EUROPE, c. 1815–1850 Zarko Cvejic, Ph. D. Cornell University 2011 The purpose of this dissertation is to offer a novel reading of the steady decline that instrumental virtuosity underwent in its critical reception between c. 1815 and c. 1850, represented here by a selection of the most influential music periodicals edited in Europe at that time. In contemporary philosophy, the same period saw, on the one hand, the reconceptualization of music (especially of instrumental music) from ―pleasant nonsense‖ (Sulzer) and a merely ―agreeable art‖ (Kant) into the ―most romantic of the arts‖ (E. T. A. Hoffmann), a radically disembodied, aesthetically autonomous, and transcendent art and on the other, the growing suspicion about the tenability of the free subject of the Enlightenment. This dissertation‘s main claim is that those three developments did not merely coincide but, rather, that the changes in the aesthetics of music and the philosophy of subjectivity around 1800 made a deep impact on the contemporary critical reception of instrumental virtuosity. More precisely, it seems that instrumental virtuosity was increasingly regarded with suspicion because it was deemed incompatible with, and even threatening to, the new philosophic conception of music and via it, to the increasingly beleaguered notion of subjective freedom that music thus reconceived was meant to symbolize. -

Dissertation FINAL 5 22

ABSTRACT Title: BEETHOVEN’S VIOLINISTS: THE INFLUENCE OF CLEMENT, VIOTTI, AND THE FRENCH SCHOOL ON BEETHOVEN’S VIOLIN COMPOSITIONS Jamie M Chimchirian, Doctor of Musical Arts, 2016 Dissertation directed by: Dr. James Stern Department of Music Over the course of his career, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827) admired and befriended many violin virtuosos. In addition to being renowned performers, many of these virtuosos were prolific composers in their own right. Through their own compositions, interpretive style and new technical contributions, they inspired some of Beethoven’s most beloved violin works. This dissertation places a selection of Beethoven’s violin compositions in historical and stylistic context through an examination of related compositions by Giovanni Battista Viotti (1755–1824), Pierre Rode (1774–1830) and Franz Clement (1780–1842). The works of these violin virtuosos have been presented along with those of Beethoven in a three-part recital series designed to reveal the compositional, technical and artistic influences of each virtuoso. Viotti’s Violin Concerto No. 2 in E major and Rode’s Violin Concerto No. 10 in B minor serve as examples from the French violin concerto genre, and demonstrate compositional and stylistic idioms that affected Beethoven’s own compositions. Through their official dedications, Beethoven’s last two violin sonatas, the Op. 47, or Kreutzer, in A major, dedicated to Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Op. 96 in G major, dedicated to Pierre Rode, show the composer’s reverence for these great artistic personalities. Beethoven originally dedicated his Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 61, to Franz Clement. This work displays striking similarities to Clement’s own Violin Concerto in D major, which suggests that the two men had a close working relationship and great respect for one another. -

An Exploration of Violin Repertoire from the Baroque Era to Present Day by Christina M. Adams a Dissertation

Versatile Violin: An Exploration of Violin Repertoire from the Baroque Era to Present Day by Christina M. Adams A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts (Music: Performance) in the University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Aaron Berofsky, Chair Professor Richard Aaron Professor Evan Chambers Professor Colleen Conway Assistant Professor Kathryn Votapek Professor Terry Wilfong Christina M. Adams [email protected] ORCID ID: 0000-0002-1470-9921 © Christina M. Adams 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to acknowledge my professors for their wisdom and guidance, as this project would not have been possible without them; My parents, Liz and John, for their endless support; And my husband, Sungho, for his constant encouragement. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ii LIST OF FIGURES iv ABSTRACT v RECITAL 1 1 Recital 1 Program 1 Recital 1 Program Notes 2 RECITAL 2 Recital 2 Program 11 Recital 2 Program Notes 12 RECITAL 3 Recital 3 Program 20 Recital 3 Program Notes 21 BIBLIOGRAPHY 30 iii LIST OF FIGURES Figure Page 1.1 String Quartet (1931)- Andante 8 2.1 “The Later Folia” 13 2.2 “Staccato-Legato” 14 2.3 “The Devil’s Trill” 19 3.1 Sonata no. 2- “Blues” 25 3.2 The Fire Hose Reel- “Siren” 26 3.3 “Shuffle Step” from String Circle 28 iv ABSTRACT Three violin recitals were given in lieu of a written dissertation. The selections in these recitals explore the violin’s versatility. The first recital Wonder Women: Works by Female Composers was comprised of works by Louise Farrenc, Lili Boulanger, Augusta Read Thomas, Chihchun Chi-sun Lee, and Ruth Crawford Seeger. -

City Research Online

City Research Online City, University of London Institutional Repository Citation: Pace, I. (2012). Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century. In: Lawson, C. and Stowell, R. (Eds.), The Cambridge History of Musical Performance. (pp. 643-695). Cambridge University Press. This is the accepted version of the paper. This version of the publication may differ from the final published version. Permanent repository link: https://openaccess.city.ac.uk/id/eprint/6305/ Link to published version: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/CHOL9780521896115.027 Copyright: City Research Online aims to make research outputs of City, University of London available to a wider audience. Copyright and Moral Rights remain with the author(s) and/or copyright holders. URLs from City Research Online may be freely distributed and linked to. Reuse: Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. City Research Online: http://openaccess.city.ac.uk/ [email protected] C:/ITOOLS/WMS/CUP-NEW/2654833/WORKINGFOLDER/LASL/9780521896115C26.3D 643 [643–695] 5.9.2011 7:13PM . 26 . Instrumental performance in the nineteenth century IAN PACE 1815–1848 Beethoven, Schubert and musical performance in Vienna from the Congress until 1830 As a major centre with a long tradition of performance, Vienna richly reflects