Theodore Tilton at Ohio Wesleyan University, and Bid Him Into Phi Kappa Psi

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hoosier Hard Times - Life Was a Strange, Colorful Kaleidoscopic Welter Then

one Hoosier Hard Times - Life was a strange, colorful kaleidoscopic welter then. It has remained so ever since. A HOOSIER HOLIDAY since her marriage in 1851, Sarah Schänäb Dreiser had given birth al- most every seventeen or eighteen months. Twelve years younger than her husband, this woman of Moravian-German stock had eloped with John Paul Dreiser at the age of seventeen. If the primordial urge to reproduce weren’t enough to keep her regularly enceinte, religious forces were. For Theodore Dreiser’s father, a German immigrant from a walled city near the French border more than ninety percent Catholic, was committed to prop- agating a faith his famous son would grow up to despise. Sarah’s parents were Mennonite farmers near Dayton, Ohio, their Czechoslovakian ances- tors having migrated west through the Dunkard communities of German- town, Bethlehem, and Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania. Sarah’s father disowned his daughter for marrying a Catholic and converting to his faith. At 8:30 in the morning of August 27, 1871, Hermann Theodor Dreiser became her twelfth child. He began in a haze of superstition and summer fog in Terre Haute, Indiana, a soot-darkened industrial town on the banks of the Wabash about seventy-five miles southwest of Indianapolis. His mother, however, seems to have been a somewhat ambivalent par- ent even from the start. After bearing her first three children in as many years, Sarah apparently began to shrink from her maternal responsibilities, as such quick and repeated motherhood sapped her youth. Her restlessness drove her to wish herself single again. -

Boxed out of The

BOXED OUT OF THE NBA REMEMBERING THE EASTERN PROFESSIONAL BASKETBALL LEAGUE BY SYL SOBEL AND JAY ROSENSTEIN “Syl and Jay brought me back to my brief playing days in the Eastern League! The small towns, the tiny gyms, the rabid fans, the colorful owners, and most of all the seriously good players who played with an edge because they fell one step short of the NBA. All the characters, the stories, and the brutally tough competition – it’s all here. About time the Eastern League got some love!”— Charley Rosen, author, basketball commentator, and former Eastern League player and CBA coach In Boxed out of the NBA: Remembering the Eastern Professional Basketball League, Syl Sobel and Jay Rosenstein tell the fascinating story of a league that was a pro basketball institution for over 30 years, showcasing top players from around the country. During the early years of professional basketball, the Eastern League was the next-best professional league in the world after the NBA. It was home to big-name players such as Sherman White, Jack Molinas, and Bill Spivey, who were implicated in college gambling scandals in the 1950s and were barred from the NBA, and top Black players such as Hal “King” Lear, Julius McCoy, and Wally Choice, who could not make the NBA into the early 1960s due to unwritten team quotas on African-American players. Featuring interviews with some 40 former Eastern League coaches, referees, fans, and players—including Syracuse University coach Jim Boeheim, former Temple University coach John Chaney, former Detroit Pistons player and coach Ray Scott, former NBA coach and ESPN analyst Hubie Brown, and former NBA player and coach Bob Weiss—this book provides an intimate, first-hand account of small-town professional basketball at its best. -

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the HBSC Collection

Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Harriet Beecher Stowe Center’s Collections Finding Aid To schedule a research appointment, please call the Collections Manager at 860.522.9258 ext. 313 or email [email protected] Harriet Beecher Stowe Papers in the Stowe Center's Collection Note: See end of document for manuscript type definitions. Manuscript type & Recipient Title Date Place length Collection Summary Other Information [Stowe's first known letter] Ten year-old Harriet Beecher writes to her older brother Edward attending Yale. She would like to see "my little sister Isabella". Foote family news. Talks of spending the Nutplains summer at Nutplains. Asks him to write back. Loose signatures of Beecher, Edward (1803-1895) 1822 March 14 [Guilford, CT] ALS, 1 pp. Acquisitions Lyman Beecher and HBS. Album which belonged to HBS; marbelized paper with red leather spine. First written page inscribed: Your Affectionate Father Lyman At end, 1 1/2-page mss of a 28 verse, seven Beecher Sufficient to the day is the evil thereof. Hartford Aug 24, stanza poem, composed by Mrs. Stowe, 1840". Pages 2 and 3 include a poem. There follow 65 mss entitled " Who shall not fear thee oh Lord". poems, original and quotes, and prose from relatives and friends, This poem seems never to have been Katharine S. including HBS's teacher at Miss Pierece's school in Litchfield, CT, published. [Pub. in The Hartford Courant Autograph Bound mss, 74 Day, Bound John Brace. Also two poems of Mrs. Hemans, copied in HBS's Sunday Magazine, Sept., 1960].Several album 1824-1844 Hartford, CT pp. -

Keys MHS Girls in Humanitarian Circumstan by ALEXGIRELLI Managers, to Improve Delivery of Ces

MONDAY LOCAL NEWS INSIDE iianrhpHtpr ■Nike house purchase before board. ■Special Focus program off to good start. ■SNET moves more to Coventry exchange. What’s ■ Route 6 plan to be presented shortly. News Local/Regional Section, Page 7. Sept. 10,1990 Gulf at a glance (AP) Here, at a glance, are the Vbur Hometown Newspaper Voted 1990 New England Newspaper of the Year Newsstand Price: 35 Cents latest developments in the Per sian Gulf crisis: ■ President Bush said die iHanrliPstrr HrralJi Red Sox triumph Helsinki summit with Soviet President Mikhail S. Gorbachev resulted m a “loud and clear” condemnation of Iraq’s Saddam over Mariners Morrison set on Hussein. Bush played down Gorbachev s reluctance to go — along with the U.S. threat of see page 45 force if sanctions fail to force SPORTS Iraq to wiUidraw from Kuwait reorganizing and unwillingness to remove the remaining 150 Soviet military advisers from Iraq. government ■ Food shipments to Iraq and occupied Kuwait will be allowed keys MHS girls in humanitarian circumstan By ALEXGIRELLI managers, to improve delivery of ces. Bush and Gorbachev Manchester Herald services. agreed. They said the United He said the objectives of state Nations, whose Security Council Indians looking MANCHESTER —Bruce Mor voted Aug. 6 to embargo all Please see MORRISON, page 6. rison, the convention-endorsed trade with Iraq because it had in o Democratic candidate for governor, vaded Kuwait four days earlier, 33 TI to advance further says the state needs to reorder its would define the special cir 2 F priorities and he says he is the best Herald support cumstances. -

Cromwelliana 2012

CROMWELLIANA 2012 Series III No 1 Editor: Dr Maxine Forshaw CONTENTS Editor’s Note 2 Cromwell Day 2011: Oliver Cromwell – A Scottish Perspective 3 By Dr Laura A M Stewart Farmer Oliver? The Cultivation of Cromwell’s Image During 18 the Protectorate By Dr Patrick Little Oliver Cromwell and the Underground Opposition to Bishop 32 Wren of Ely By Dr Andrew Barclay From Civilian to Soldier: Recalling Cromwell in Cambridge, 44 1642 By Dr Sue L Sadler ‘Dear Robin’: The Correspondence of Oliver Cromwell and 61 Robert Hammond By Dr Miranda Malins Mrs S C Lomas: Cromwellian Editor 79 By Dr David L Smith Cromwellian Britain XXIV : Frome, Somerset 95 By Jane A Mills Book Reviews 104 By Dr Patrick Little and Prof Ivan Roots Bibliography of Books 110 By Dr Patrick Little Bibliography of Journals 111 By Prof Peter Gaunt ISBN 0-905729-24-2 EDITOR’S NOTE 2011 was the 360th anniversary of the Battle of Worcester and was marked by Laura Stewart’s address to the Association on Cromwell Day with her paper on ‘Oliver Cromwell: a Scottish Perspective’. ‘Risen from Obscurity – Cromwell’s Early Life’ was the subject of the study day in Huntingdon in October 2011 and three papers connected with the day are included here. Reflecting this subject, the cover illustration is the picture ‘Cromwell on his Farm’ by Ford Madox Brown (1821–1893), painted in 1874, and reproduced here courtesy of National Museums Liverpool. The painting can be found in the Lady Lever Art Gallery in Port Sunlight Village, Wirral, Cheshire. In this edition of Cromwelliana, it should be noted that the bibliography of journal articles covers the period spring 2009 to spring 2012, addressing gaps in the past couple of years. -

Schuyler Colfax Collection L036

Schuyler Colfax collection L036 This finding aid was produced using the Archivists' Toolkit August 03, 2015 Describing Archives: A Content Standard Rare Books and Manuscripts 140 North Senate Avenue Indianapolis, Indiana, 46204 317-232-3671 Schuyler Colfax collection L036 Table of Contents Summary Information ................................................................................................................................. 3 Biographical Note.......................................................................................................................................... 4 Scope and Contents....................................................................................................................................... 4 Arrangement...................................................................................................................................................5 Administrative Information .........................................................................................................................6 Controlled Access Headings..........................................................................................................................7 Collection Inventory...................................................................................................................................... 9 Series 1: Correspondence, 1782-1927.....................................................................................................9 Series 2: Subject files, 1875-1970.........................................................................................................32 -

THE NCAA NEWS/March A,1988 Two Attendance Records Set at ‘88 Convention in Nashville Two NCAA Convention Attend- Percent

Official Publication of the National Collegiate Athletic Association March 9,1988, Volume 25 Number 10 House overwhelmingly passes bill to broaden Title IX scope The House overwhelmingly discrimination in Federally funded rent law to provide that entire insti- passed a landmark civil-rights bill education programs applies only tutions and government agencies March 3 that would broaden the to specific programs or activities are covered if any program or activ- scope of Title IX and three other receiving Federal assistanceand not ity within them receivesFederal aid. statutes, but President Reagan has to the entire institutions of which The broad coverage also applies to vowed to veto the measure. they are part. the private sector if the aid goes to a The Civil Rights Restoration Act Supporters of the act said corporation as a whole or if the was sent to the White House on a hundreds of discrimination corn- recipient principally provides cdu- 3 15-98vote. The Senate passedit by plaints had been dropped or rcs- cation, health care, housing, social an equally lopsided 75-14 vote in tricted since the decision, the services or parks and recreation. January. Associated Press reported. In addition to Title IX ofthe 1972 In letters delivered to several Education Amendments, the act Both chambers passed the bill by amends three other civil-rights laws House Republicans, Reagan said the two-thirds margin needed to potentially affected by the Supreme override a presidential veto, but it flatly he will veto the measure “if it is presented to me in its current Court ruling: the 1964 Civil Rights was unclear whether the margins Act, barring racial discrimination in form.” would hold up following Reagan’s Federally assisted programs; the vow to reject the measure. -

The National Archives Prob 11/156/285 1 ______

THE NATIONAL ARCHIVES PROB 11/156/285 1 ________________________________________________________________________ SUMMARY: The document below is the Prerogative Court of Canterbury copy of the will, dated 15 August 1629 and proved 8 October 1629, of Robert Radcliffe (1573 – 22 September 1629), 5th Earl of Sussex, to whom Robert Greene dedicated Thomas Lodge’s Euphues’ Shadow (1592). The testator was the son of Henry Radcliffe (1533 – 14 December 1593), 4th Earl of Sussex, and Honor Pounde (d.1593), the daughter of Anthony Pounde (d.1547) of Farlington, Hampshire, and Anne Wingfield (d. 13 November 1557). For Anthony Pounde (d.1547), see the will of his father, William Pounde (d. 5 July 1525), TNA PROB 11/21/561. Anthony Pounde’s half brother, William Pounde (died c.1564?), married Ellen Wriothesley (d.1589), great-aunt of Henry Wriothesley (1573-1624), 3rd Earl of Southampton. The testator’s father, Henry Radcliffe (1533-1593), 4th Earl of Sussex, and his elder brother, Thomas Radcliffe (1527-1583), 3rd Earl of Sussex, were the sons of Henry Radcliffe (d.1557), 2nd Earl of Sussex, and his first wife, Elizabeth Howard (d.1534), daughter of Thomas Howard (1443-1524), 2nd Duke of Norfolk. Elizabeth Howard’s nephew, Henry Howard (1517-1547), married Oxford’s aunt, Frances de Vere (d.1577). The testator married Bridget Morison (baptized 1575, d.1623), the daughter of Sir Charles Morison (1549 – 31 March 1599), by whom he had two sons and two daughters, all of whom predeceased the testator. For the will of Sir Charles Morison, see TNA PROB 11/94/168. Bridget Morison’s grandmother, Bridget Hussey Morrison Manners Russell (1525/6–1601), Countess of Bedford, had the care of Oxford's daughters, Bridget and Susan Vere after the death of their grandfather, Lord Burghley, and was the grandmother of Francis Norris (1579-1622), Earl of Berkshire, who married Oxford's daughter, Bridget de Vere (1584–1630/31?). -

Kit-Cat Related Poetry

‘IN AND OUT’: AN ANALYSIS OF KIT-CAT CLUB MEMBERSHIP (Web Appendix to The Kit-Cat Club by Ophelia Field, 2008) There are four main primary sources with regard to the membership of the Kit-Cat Club – Abel Boyer’s 1722 list,1 John Oldmixon’s 1735 list,2 a Club subscription list dated 1702,3 and finally the portraits painted by Sir Godfrey Kneller between 1697 and 1721 (as well as the 1735 Faber engravings of these paintings). None of the sources agree. Indeed, only the membership of four men (Dr Garth, Lord Cornwallis, Spencer Compton and Abraham Stanyan) is confirmed by all four of these sources. John Macky, a Whig journalist and spy, was the first source for the statement that the Club could have no more than thirty-nine members at any one time,4 and Malone and Spence followed suit.5 It is highly unlikely that there were so many members at the Kit-Cat’s inception, however, and membership probably expanded with changes of venue, especially around 1702–3. By 1712–14, all surviving manuscript lists of toasted ladies total thirty-nine, suggesting that there was one lady toasted by each member and therefore that Macky was correct.6 The rough correlation between the dates of expulsions/deaths and the dates of new admissions (such as the expulsion of Prior followed by the admission of Steele in 1705) also supports the hypothesis that at some stage a cap was set on the size of the Club. Allowing that all members were not concurrent, most sources estimate between forty- six and fifty-five members during the Club’s total period of activity.7 There are forty- four Kit-Cat paintings, but Oldmixon, who got his information primarily from his friend Arthur Maynwaring, lists forty-six members. -

Download This Issue As A

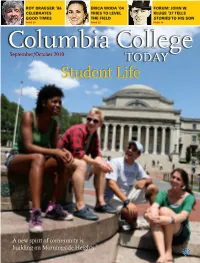

ROY BRAEGER ‘86 Erica Woda ’04 FORUM: JOHN W. CELEBRATES Tries TO LEVel KLUGE ’37 TELLS GOOD TIMES THE FIELD STORIES TO HIS SON Page 59 Page 22 Page 24 Columbia College September/October 2010 TODAY Student Life A new spirit of community is building on Morningside Heights ’ll meet you for a I drink at the club...” Meet. Dine. Play. Take a seat at the newly renovated bar grill or fine dining room. See how membership in the Columbia Club could fit into your life. For more information or to apply, visit www.columbiaclub.org or call (212) 719-0380. The Columbia University Club of New York 15 West 43 St. New York, N Y 10036 Columbia’s SocialIntellectualCulturalRecreationalProfessional Resource in Midtown. Columbia College Today Contents 24 14 68 31 12 22 COVER STORY ALUMNI NEWS DEPARTMENTS 30 2 S TUDENT LIFE : A NEW B OOK sh E L F LETTER S TO T H E 14 Featured: David Rakoff ’86 EDITOR S PIRIT OF COMMUNITY ON defends pessimism but avoids 3 WIT H IN T H E FA MI L Y M ORNING S IDE HEIG H T S memoirism in his new collec- tion of humorous short stories, 4 AROUND T H E QU A D S Satisfaction with campus life is on the rise, and here Half Empty: WARNING!!! No 4 are some of the reasons why. Inspirational Life Lessons Will Be Homecoming 2010 Found In These Pages. 5 By David McKay Wilson Michael B. Rothfeld ’69 To Receive 32 O BITU A RIE S Hamilton Medal 34 Dr. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

Brian Knight

STRATEGY, MISSION AND PEOPLE IN A RURAL DIOCESE A CRITICAL EXAMINATION OF THE DIOCESE OF GLOUCESTER 1863-1923 BRIAN KNIGHT A thesis submitted to the University of Gloucestershire in accordance with the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts and Humanities August, 2002 11 Strategy, Mission and People in a Rural Diocese A critical examination of the Diocese of Gloucester 1863-1923 Abstract A study of the relationship between the people of Gloucestershire and the Church of England diocese of Gloucester under two bishops, Charles John Ellicott and Edgar Charles Sumner Gibson who presided over a mainly rural diocese, predominantly of small parishes with populations under 2,000. Drawing largely on reports and statistics from individual parishes, the study recalls an era in which the class structure was a dominant factor. The framework of the diocese, with its small villages, many of them presided over by a squire, helped to perpetuate a quasi-feudal system which made sharp distinctions between leaders and led. It is shown how for most of this period Church leaders deliberately chose to ally themselves with the power and influence of the wealthy and cultured levels of society and ostensibly to further their interests. The consequence was that they failed to understand and alienated a large proportion of the lower orders, who were effectively excluded from any involvement in the Church's affairs. Both bishops over-estimated the influence of the Church on the general population but with the twentieth century came the realisation that the working man and women of all classes had qualities which could be adapted to the Church's service and a wider lay involvement was strongly encouraged.