A Kit Barks in Fright. Turning Gelding up with Consequently Has Lost Tries To

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ffandm Tnr Ctsttina V M O AVBRA4W DAILV Cnocixtion a L W

.:^J\,:. U V l UONDAT. lCAIUaia,.XM( ffandm tnr CtSttina V m O AVBRA4W DAILV CnOCiXTION A l W ................... ................................♦ . ^ f - v fsr Ihs sraalb sf FShrasry, its i SliirCHDRCHCBOIR RAND TARES CHARIZ ford. „ U m Boot Caterere cf New m O T T O W H PRAISES VEIiRAN^’ Y.M.C.A.No7 ^ Haven wUl cater. SELL MANY HCKEIS N. B. Riehaids. Rony N. Roth 5 . 8 7 6 ^ Msmber sf Ihs AafM 2flA ativlTFB ™ ]r Iw U P u in n IS aprclill IN TORD HDSICAL Maseh S> and George R. Waddell ore co-chair GIFTS FOR EASTER TM b« Na. Itai- OFOTADEISRVICES Barsaa sf Ctasalstlsas O r t e t€ Bad U m wm hold HELP IN DISASTERS 4:00—Grade School vs. Alumni men o f the benefit bon. Arthur A . MRS. B LU O TTS j tUa •vmtiiK la Basketball gams. FOR SHRINERS BALL Knolla to choinnoa of the ticket RUG AND mFT SHOP M AN(m STER — A (TTY OF VILLAGE (HARM Prognmi !■ in Keeping With f Ban «t • 0’elBdi ahaip. S:1S—Busineaa Men’s VoDay ball Appropriate Mnrical Proenua committee and Albert Dewey heads tbs uriMn oonunlttes. 997 Bfain Street Holr Wedi; Solm bjr Min lass. Yesterday at Ail Three Sal- VOL. LVL, NO. 147 oa Fage M.) MANCHBStBR, C0NN„ TUESDAY, MARCH 23, 1937 (TWELVE PAGES) rltttbe| Winard and Robert Gordon. 0:SO—Milk Dedlers’ aasodattoa Rsssrvatloos for boxos should be D. A. V. Banquet Speaker upper meeting. vatitei A m y Meetings. mode with Albert icnnoe, td. 4886. ationi AO Proceeds fro n Dance O i I oatranitjr. -

Jockey Records

JOCKEYS, KENTUCKY DERBY (1875-2020) Most Wins Jockey Derby Span Mts. 1st 2nd 3rd Kentucky Derby Wins Eddie Arcaro 1935-1961 21 5 3 2 Lawrin (1938), Whirlaway (’41), Hoop Jr. (’45), Citation (’48) & Hill Gail (’52) Bill Hartack 1956-1974 12 5 1 0 Iron Liege (1957), Venetian Way (’60), Decidedly (’62), Northern Dancer-CAN (’64) & Majestic Prince (’69) Bill Shoemaker 1952-1988 26 4 3 4 Swaps (1955), Tomy Lee-GB (’59), Lucky Debonair (’65) & Ferdinand (’86) Isaac Murphy 1877-1893 11 3 1 2 Buchanan (1884), Riley (’90) & Kingman (’91) Earle Sande 1918-1932 8 3 2 0 Zev (1923), Flying Ebony (’25) & Gallant Fox (’30) Angel Cordero Jr. 1968-1991 17 3 1 0 Cannonade (1974), Bold Forbes (’76) & Spend a Buck (’85) Gary Stevens 1985-2016 22 3 3 1 Winning Colors (1988), Thunder Gulch (’95) & Silver Charm (’98) Kent Desormeaux 1988-2018 22 3 1 4 Real Quiet (1998), Fusaichi Pegasus (2000) & Big Brown (’08) Calvin Borel 1993-2014 12 3 0 1 Street Sense (2007), Mine That Bird (’09) & Super Saver (’10) Victor Espinoza 2001-2018 10 3 0 1 War Emblem (2002), California Chrome (’14) & American Pharoah (’15) John Velazquez 1996-2020 22 3 2 0 Animal Kingdom (2011), Always Dreaming (’17) & Authentic (’20) Willie Simms 1896-1898 2 2 0 0 Ben Brush (1896) & Plaudit (’98) Jimmy Winkfield 1900-1903 4 2 1 1 His Eminence (1901) & Alan-a-Dale (’02) Johnny Loftus 1912-1919 6 2 0 1 George Smith (1916) & Sir Barton (’19) Albert Johnson 1922-1928 7 2 1 0 Morvich (1922) & Bubbling Over (’26) Linus “Pony” McAtee 1920-1929 7 2 0 0 Whiskery (1927) & Clyde Van Dusen (’29) Charlie -

MJC Media Guide

2021 MEDIA GUIDE 2021 PIMLICO/LAUREL MEDIA GUIDE Table of Contents Staff Directory & Bios . 2-4 Maryland Jockey Club History . 5-22 2020 In Review . 23-27 Trainers . 28-54 Jockeys . 55-74 Graded Stakes Races . 75-92 Maryland Million . 91-92 Credits Racing Dates Editor LAUREL PARK . January 1 - March 21 David Joseph LAUREL PARK . April 8 - May 2 Phil Janack PIMLICO . May 6 - May 31 LAUREL PARK . .. June 4 - August 22 Contributors Clayton Beck LAUREL PARK . .. September 10 - December 31 Photographs Jim McCue Special Events Jim Duley BLACK-EYED SUSAN DAY . Friday, May 14, 2021 Matt Ryb PREAKNESS DAY . Saturday, May 15, 2021 (Cover photo) MARYLAND MILLION DAY . Saturday, October 23, 2021 Racing dates are subject to change . Media Relations Contacts 301-725-0400 Statistics and charts provided by Equibase and The Daily David Joseph, x5461 Racing Form . Copyright © 2017 Vice President of Communications/Media reproduced with permission of copyright owners . Dave Rodman, Track Announcer x5530 Keith Feustle, Handicapper x5541 Jim McCue, Track Photographer x5529 Mission Statement The Maryland Jockey Club is dedicated to presenting the great sport of Thoroughbred racing as the centerpiece of a high-quality entertainment experience providing fun and excitement in an inviting and friendly atmosphere for people of all ages . 1 THE MARYLAND JOCKEY CLUB Laurel Racing Assoc. Inc. • P.O. Box 130 •Laurel, Maryland 20725 301-725-0400 • www.laurelpark.com EXECUTIVE OFFICIALS STATE OF MARYLAND Sal Sinatra President and General Manager Lawrence J. Hogan, Jr., Governor Douglas J. Illig Senior Vice President and Chief Financial Officer Tim Luzius Senior Vice President and Assistant General Manager Boyd K. -

Santa Anita Derby Santa Anita Derby

Saturday, April 8, 2017 $1,000,000$750,000 SANTA ANITA DERBY SANTA ANITA DERBY EXAGGERATOR Dear Member of the Media: Now in its 82nd year of Thoroughbred racing, Santa Anita is proud to have hosted many of the sport’s greatest moments. Although the names of its historic human and horse heroes may have changed in SANTA ANITA DERBY $1,000,000 Guaranteed (Grade I) the past seven decades of racing, Santa Anita’s prominence in the sport Saturday, April 8, 2017 • Eightieth Running remains constant. Gross Purse: $1,000,000 Winner’s Share: $600,000 This year, Santa Anita will present the 80th edition of the Gr. I, Other Awards: $200,000 second; 120,000 third; $50,000 fourth; $20,000 fifth; $1,000,000 Santa Anita Derby on Saturday, April 8. $10,000 sixth Distance: One and one-eighth miles on the main track The Santa Anita Derby is the premier West Coast steppingstone to Nominations: Early Bird nominations at $500 closed December 26, 2016; the Triple Crown, with 34 Santa Anita Derby starters having won a total Regular nominations close March 25, 2017 by payment of of 40 Triple Crown races. $2,500; Supplementary nominations at $20,000 due at time of entry Track Record: 1:45 4/5, Star Spangled, 5 (Laffit Pincay, Jr., 117, March 24, If you have questions regarding the 2017 Santa Anita Derby, or if 1979, San Bernardino Handicap) you are interested in obtaining credentials, please contact the Publicity Stakes Record: 1:47, Lucky Debonair (Bill Shoemaker, 118, March 6, 1965); Department at your convenience. -

$400,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU

$400,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU (Grade III) 95th Running – Saturday, May 4, 2019 (Kentucky Derby Day) 3-Year-Olds at One Mile on Dirt at Churchill Downs Stakes Record – 1:34.18, Competitive Edge (2015) Track Record – 1:33.26, Fruit Ludt (2014) Name Origin: Formerly known as the Derby Trial, the one-mile race for 3-year-olds was moved from Opening Night to Kentucky Derby Day and renamed the Pat Day Mile in 2015 to honor Churchill Downs’ all-time leading jockey Pat Day. Day, enshrined in the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame in 2005, won a record 2,482 races at Churchill Downs, including 156 stakes, from 1980-2005. None was more memorable than his triumph aboard W.C. Partee’s Lil E. Tee in the 1992 Kentucky Derby. He rode in a record 21 consecutive renewals of the Kentucky Derby, a streak that ended when hip surgery forced him to miss the 2005 “Run for the Roses.” Day’s Triple Crown résumé also included five wins in the Preakness Stakes – one short of Eddie Arcaro’s record – and three victories in the Belmont Stakes. His 8,803 career wins rank fourth all-time and his mounts that earned $297,914,839 rank second. During his career Day lead the nation in wins six times (1982-84, ’86, and ’90-91). His most prolific single day came on Sept. 13, 1989, when Day set a North American record by winning eight races from nine mounts at Arlington Park. -

Bob Baffert, Five Others Enter Hall of Fame

FREE SUBSCR ER IPT IN IO A N R S T COMPLIMENTS OF T !2!4/'! O L T IA H C E E 4HE S SP ARATOGA Year 9 • No. 15 SARATOGA’S DAILY NEWSPAPER ON THOROUGHBRED RACING Friday, August 14, 2009 Head of the Class Bob Baffert, five others enter Hall of Fame Inside F Hall of Famer profiles Racing UK F Today’s entries and handicapping PPs Inside F Dynaski, Mother Russia win stakes DON’T BOTHER CHECKING THE PHOTO, THE WINNER IS ALWAYS THE SAME. YOU WIN. You win because that it generates maximum you love explosive excitement. revenue for all stakeholders— You win because AEG’s proposal including you. AEG’s proposal to upgrade Aqueduct into a puts money in your pocket world-class destination ensuress faster than any other bidder, tremendous benefits for you, thee ensuring the future of thorough- New York Racing Associationn bred racing right here at home. (NYRA), and New York Horsemen, Breeders, and racing fans. THOROUGHBRED RACING MUSEUM. AEG’s Aqueduct Gaming and Entertainment Facility will have AEG’s proposal includes a Thoroughbred Horse Racing a dazzling array Museum that will highlight and inform patrons of the of activities for VLT REVENUE wonderful history of gaming, dining, VLT OPERATION the sport here in % retail, and enter- 30 New York. tainment which LOTTERY % AEG The proposed Aqueduct complex will serve as a 10 will bring New world-class gaming and entertainment destination. DELIVERS. Yorkers and visitors from the Tri-State area and beyond back RACING % % AEG is well- SUPPORT 16 44 time and time again for more fun and excitement. -

250000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU

$250,000 Pat Day Mile Presented by LG&E and KU (Grade III) 92nd Running – Saturday, May 7, 2016 (Kentucky Derby Day) 3-Year-Olds at One Mile on Dirt at Churchill Downs Stakes Record – 1:34.18, Competitive Edge (2015) Top Beyer Speed Figure – 112, Richter Scale (1997) Average Winning Beyer Speed Figure (since 1992) – 99.9 (2,398/24) Name Origin: Formerly known as the Derby Trial, the one-mile race for 3-year-olds was moved from Opening Night to Kentucky Derby Day and renamed the Pat Day Mile in 2015 to honor Churchill Downs’ all-time leading jockey Pat Day. Day, enshrined in the National Museum of Racing’s Hall of Fame in 2005, won a record 2,482 races at Churchill Downs, including 156 stakes, from 1980-2005. None was more memorable than his triumph aboard W.C. Partee’s Lil E. Tee in the 1992 Kentucky Derby. He rode in a record 21 consecutive renewals of the Kentucky Derby, a streak that ended when hip surgery forced him to miss the 2005 “Run for the Roses.” Day’s Triple Crown résumé also included five wins in the Preakness Stakes – one short of Eddie Arcaro’s record – and three victories in the Belmont Stakes. His 8,803 career wins rank fourth all-time and his mounts that earned $297,914,839 rank second. During his career Day lead the nation in wins six times (1982-84, ’86, and ’90-91). His most prolific single day came on Sept. 13, 1989, when Day set a North American record by winning eight races from nine mounts at Arlington Park. -

Run for the Roses May 1 Marks the 136Th Running of the Kentucky Derby — One of the World’S Largest and Richest Sporting Events

Vol. 30 • No. 4 ComplimeNtary Copy april 2010 Florida’s Leading Newspaper For Active, Mature Adults Run for the Roses May 1 marks the 136th running of the Kentucky Derby — one of the world’s largest and richest sporting events. Whether you visit Churchill Downs in person, host your own Derby Day party or catch the action at our own Tampa Bay Downs, this issue of Senior Voice will guide you. For more than 135 years, the Kentucky From the time Kentucky was settled, Derby has been everyone’s race. From the fields of the Bluegrass region were dapper men and beautiful women in noted for producing superior race hats sipping on frosty mint juleps to the horses. laid-back infield crowd who picnic on In 1872, Col. Meriwether Lewis Clark, fried chicken and toss Frisbees, Churchill Jr., grandson of William Clark of the Downs, near Louisville, welcomes more Lewis and Clark expedition, traveled than 150,000 spectators to witness the to England, visiting the Epsom Derby, most thrilling two minutes in sports. a famous race that had been running “Riders up” booms the paddock annually since 1780. judge… From there, Clark went on to Paris, Trainers give a leg up to the riders; where in 1863, a group of racing enthusi- and send them out through the tunnel asts had formed the French Jockey Club and onto the world’s most famous track and had organized the Grand Prix de as the University of Louisville band Paris, which at the time was the greatest strikes up Stephen Foster’s “My Old race in France. -

Preakness Stakes .Fifty-Three Fillies Have Competed in the Preakness with Start in 1873: Rfive Crossing the Line First The

THE PREAKNESS Table of Contents (Preakness Section) History . .P-3 All-Time Starters . P-31. Owners . P-41 Trainers . P-45 Jockeys . P-55 Preakness Charts . P-63. Triple Crown . P-91. PREAKNESS HISTORY PREAKNESS FACTS & FIGURES RIDING & SADDLING: WOMEN & THE MIDDLE JEWEL: wo people have ridden and sad- dled Preakness winners . Louis J . RIDERS: Schaefer won the 1929 Preakness Patricia Cooksey 1985 Tajawa 6th T Andrea Seefeldt 1994 Looming 7th aboard Dr . Freeland and in 1939, ten years later saddled Challedon to victory . Rosie Napravnik 2013 Mylute 3rd John Longden duplicated the feat, win- TRAINERS: ning the 1943 Preakness astride Count Judy Johnson 1968 Sir Beau 7th Fleet and saddling Majestic Prince, the Judith Zouck 1980 Samoyed 6th victor in 1969 . Nancy Heil 1990 Fighting Notion 5th Shelly Riley 1992 Casual Lies 3rd AFRICAN-AMERICAN Dean Gaudet 1992 Speakerphone 14th RIDERS: Penny Lewis 1993 Hegar 9th Cynthia Reese 1996 In Contention 6th even African-American riders have Jean Rofe 1998 Silver’s Prospect 10th had Preakness mounts, including Jennifer Pederson 2001 Griffinite 5th two who visited the winners’ circle . S 2003 New York Hero 6th George “Spider” Anderson won the 1889 Preakness aboard Buddhist .Willie Simms 2004 Song of the Sword 9th had two mounts, including a victory in Nancy Alberts 2002 Magic Weisner 2nd the 1898 Preakness with Sly Fox “Pike”. Lisa Lewis 2003 Kissin Saint 10th Barnes was second with Philosophy in Kristin Mulhall 2004 Imperialism 5th 1890, while the third and fourth place Linda Albert 2004 Water Cannon 10th finishers in the 1896 Preakness were Kathy Ritvo 2011 Mucho Macho Man 6th ridden by African-Americans (Alonzo Clayton—3rd with Intermission & Tony Note: Penny Lewis is the mother of Lisa Lewis Hamilton—4th on Cassette) .The final two to ride in the middle jewel are Wayne Barnett (Sparrowvon, 8th in 1985) and MARYLAND MY Kevin Krigger (Goldencents, 5th in 2013) . -

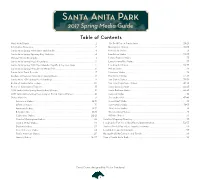

Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance

Santa Anita Park 2017 Spring Media Guide Table of Contents Meet-At-A-Glance . 2 The Gold Cup at Santa Anita . 28-29 Information Resources . 3 Honeymoon Stakes . 30-31 Santa Anita Spring Attendance and Handle . 4 Kona Gold Stakes . 31 Santa Anita Spring Opening Day Statistics . 4 Landaluce Stakes . 32-33 Michael Wrona Biography . 4 Lazaro Barrera Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring Meet Attendance . 5 Lennyfrommalibu Stakes . 33 Santa Anita Spring 2016 Meet Handle, Payoffs & Top Five Days . 5 Los Angeles Stakes . 34-35 Santa Anita Spring Meet Annual Media Poll . 6 Melair Stakes . 36 Santa Anita Track Records . 7 Monrovia Stakes . 36 Leaders at Previous Santa Anita Spring Meets . 8 Precisionist Stakes . 37-38 Santa Anita 2016 Spring Meet Standings . 9 San Carlos Stakes . 38-39 Roster of Santa Anita Jockeys . 10 San Juan Capistrano Stakes . 40-41 Roster of Santa Anita Trainers . 11 Santa Anita Juvenile . 42-43 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Stakes Winners . 12 Santa Barbara Stakes . 44-45 2016 Santa Anita Spring Meet Longest Priced Stakes Winners . 12 Senorita Stakes . 46 Stakes Histories . 13 Shoemaker Mile . 47-48 Adoration Stakes . 14-15 Snow Chief Stakes . 49 Affirmed Stakes . 15 Summertime Oaks . 50-51 American Stakes . 16-17 Thor's Echo Stakes . 51 Beholder Mile . 18-19 Thunder Road Stakes . 51 Californian Stakes . 20-21 Wilshire Stakes . 52 Charles Whittingham Stakes . 22 Satellite Wagering Directory . 53 Crystal Water Stakes . 23 Los Angeles Turf Inc . Club Officers/Administration . 54-55 Daytona Stakes . 23 Visitors Guide/Map of Los Angeles Freeways . 56 Desert Stormer Stakes . 24 Local Hotels and Restaurants . -

Dash for Cash (QH) (1973)

TesioPower jadehorse Dash For Cash (QH) (1973) VOTER 1 BALLOT Cerito 14 Midway Sir Dixon 4 Thirty-Third High Degree 10 Percentage (1923) Disguise II 10 Bulse Nethersole 2 Gossip Avenue Magneto 4 Rosewood Rose Tree 18 Three Bars (1940) COMMANDO 12 Ultimus RUNNING STREAM 14 Luke McLuke Trenton 18 Midge SANDFLY 2 Myrtle Dee (1923) BEN BRUSH A1 Patriot SANDFLY 2 Civil Maid Carlsbad 12 Civil Rule Semper Victoire 4 Rocket Bar (1851) ST FRUSQUIN 22 St Amant Lady Loverule 14 Atwell Cyllene 9 Doro Scene 1 Cartago (1925) Henry Young Heno Quiver A1 Polly H Rensselaer Polly Wantage Golden Rocket (1940) VOTER 1 Runnymede RUNNING STREAM 14 Morvich Dr Leggo 4 Hymir Georgia Girl 1 Morshion (1928) Yankee 23 Nonpareil Fancywood 12 Cushion Martinet 20 Hassock Agnes Brennan 1 Rocket Wrangler (QH) (1967) Pennant 8 Equipoise Swinging 5 Equestrian Man O' War 4 Frilette Frillery A1 Top Deck (1945) Chicle 31 Chicaro Wendy 5 River Boat SIR GALLAHAD III 16 Last Boat Taps 16 Go Man Go (QH) (1953) Mentor A1 Wise Counsellor Rustle 4 Very Wise Omond Omona Simona Lightfoot Sis (QH) (1945) Dewey The Dun Horse (QH) Mais (QH) Clear Track (QH) Old Dj (QH) Ella 2 (QH) Mare By Beauregard (QH) Go Galla Go (QH) (1961) John P Grier 8 Jack High Priscilla 5 With Regards Terry 22 Loose Foot British Fleet 20 Direct Win (1947) Time Maker 4 Time Supply Surplice Gold Dream BALLOT 14 La Galla Win (QH) (1953) Plumage Glyn ? La Gallina V (QH) (1939) ? COMMANDO 12 Dash For Cash (QH) (1973) Peter Pan Cinderella 2 Black Toney BEN BRUSH A1 Belgravia Bonnie Gal 10 Broker's Tip (1930) Prestige -

New Jersey Farm Was a Racing Power for Generations

Brookdale Memories New Jersey farm was a racing power for generations By Cindy Deubler avid Dunham Withers was attracted to the fertile river-fed farmland of Lincroft, N.J., and created DBrookdale Farm in the 1870s. Philanthropist Geraldine TION C Thompson saw her home as one that should be shared with COLLE M TE S others, and in the late 1960s bequeathed a substantial portion of what was once one of the greatest farms in North America OUTH COUNTY PARK SY OUTH COUNTY PARK M to Monmouth County to be used as a park. MON 22 Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred SEPTEMBER 2013 Mid-Atlantic Thoroughbred SEPTEMBER 2013 23 TION C COLLE M TE S OUTH COUNTY PARK SY OUTH COUNTY PARK M MON With no horse in sight (other than the nation’s best stallions, boasted the finest America’s leading turfmen Withers’ land purchases from 1872 to the Withers-bred Golden Rod. The stable February 1896 – he was only 59 – it came occasional riding horse), Thompson Park – bloodlines in its broodmare band, and 1888 expanded the farm to 838 acres, and included a juvenile colt Thompson named as a huge blow to the industry. The stable the former Brookdale Farm – stands as a provided a superb training facility utilized D.D. Withers created it, Colonel William he oversaw every detail, including layout The Sage, in honor of Brookdale’s creator. was taken over by his sons, Lewis S. and glorious link to New Jersey’s golden age in by industry giants named Withers, Keene P. Thompson had great plans for it, legend- and construction.