Daniel Mannix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Television Has Long Upheld an Unspoken Rule: a Female Character May Be Beautiful Or Angry, but Never Both

PRETTY HURTS Television has long upheld an unspoken rule: A female character may be beautiful or angry, but never both. A handful of new shows prove that rules were made to be broken BY JULIA COOKE Shapely limbs swollen and wavering under longer dependent on men to be effective.” Woodley’s Jane runs hard and fast, flashing water, lipstick wiped off a pale mouth with a These days, injustice—often linked to the back to scenes of her rape and packing a gun in yellow sponge, blonde bangs caught in the zip- tangled ramifications of a heroine’s beauty— her purse to meet with a man who might be the per of a body bag: Kristy Guevara-Flanagan’s gives women license to take all sorts of juicy perpetrator. Their anger is nuanced, caused by 2016 short film What Happened to Her collects actions that are far more interesting than a range of situations, and on-screen they strug- images of dead women in a 15-minute montage killing. On Marvel’s Jessica Jones, it’s fury at gle to tame it into something else: self-defense, culled mostly from crime-based television dra- being raped and manipulated by the evil Kil- loyalty, grudges, power, career. mas. Throughout, men stand murmuring over grave that spurs the protagonist to become the The shift in representation aligns with the beautiful young white corpses. “You ever see righteously bitchy superhero she’s meant to increasing number of women behind cameras something like this?” a voice drawls. be. When her husband dumps her for his sec- in Hollywood. -

English, French, and Spanish Colonies: a Comparison

COLONIZATION AND SETTLEMENT (1585–1763) English, French, and Spanish Colonies: A Comparison THE HISTORY OF COLONIAL NORTH AMERICA centers other hand, enjoyed far more freedom and were able primarily around the struggle of England, France, and to govern themselves as long as they followed English Spain to gain control of the continent. Settlers law and were loyal to the king. In addition, unlike crossed the Atlantic for different reasons, and their France and Spain, England encouraged immigration governments took different approaches to their colo- from other nations, thus boosting its colonial popula- nizing efforts. These differences created both advan- tion. By 1763 the English had established dominance tages and disadvantages that profoundly affected the in North America, having defeated France and Spain New World’s fate. France and Spain, for instance, in the French and Indian War. However, those were governed by autocratic sovereigns whose rule regions that had been colonized by the French or was absolute; their colonists went to America as ser- Spanish would retain national characteristics that vants of the Crown. The English colonists, on the linger to this day. English Colonies French Colonies Spanish Colonies Settlements/Geography Most colonies established by royal char- First colonies were trading posts in Crown-sponsored conquests gained rich- ter. Earliest settlements were in Virginia Newfoundland; others followed in wake es for Spain and expanded its empire. and Massachusetts but soon spread all of exploration of the St. Lawrence valley, Most of the southern and southwestern along the Atlantic coast, from Maine to parts of Canada, and the Mississippi regions claimed, as well as sections of Georgia, and into the continent’s interior River. -

Launch of Mannix Library's Special Collections Room

Launch of Mannix Library’s Special Collections Room by Kerrie Burn AFALIA (DCP) Library Manager, Mannix Library, Catholic Theological College, University of Divinity On Friday 15th February 2019, a gathering was held in Mannix Library (http://www.mannix.org.au/) in East Melbourne to celebrate the launch of the library’s new Special Collections Room. The well-attended event was also an opportunity for library staff to demonstrate the library’s newly installed ElarScan A2 scanner, as well as a new website, created to showcase the library’s Archbishop Goold Special Collection. For the past two years, Mannix Library staff have been involved with a project funded by the Australian Research Council titled A Baroque Archbishop in Colonial Australia: James Alipius Goold, 1812-1886. Goold was Melbourne’s first Catholic Archbishop and made a significant contribution to colonial Melbourne, amassing significant collections of artworks and books, and commissioning the construction of St Patrick’s Cathedral. Contributions by Mannix Library staff to the Goold project to date have included: several talks and conference presentations, including at the Goold Symposium in February 2018; research into and curation of an 15 The ANZTLA EJournal, No 22 (2019) ISSN 1839-8758 exhibition of Goold books at Catholic Theological College; the creation of a website to showcase Goold’s library (https://gooldlibrary.omeka.net/); writing articles for the project’s blog; co- authorship of a chapter on Goold’s library in a forthcoming book, The Invention of Melbourne: A Baroque Archbishop and a Gothic Architect; and preparation for an exhibition of the same name being held at the Old Treasury Building in Melbourne from 31 July 2019—January 2020. -

The Current Status and Issues Surrounding Native Title in Regional Australia

284 Australasian Journal of Regional Studies, Vol. 24, No 3, 2018 NEW DIMENSIONS IN LAND TENURE – THE CURRENT STATUS AND ISSUES SURROUNDING NATIVE TITLE IN REGIONAL AUSTRALIA Jude Mannix PhD Candidate, Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. Michael Hefferan Emeritus Professor, c/- Science and Engineering Faculty, School of Civil Engineering and Built Environment, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane, Queensland, 4000, Australia. Email: [email protected]. ABSTRACT: The acquisition and use of real property is fundamental to practically all types of resource and infrastructure projects. The success of those activities is based, in no small way, on the reliability of the underlying tenure and land management systems operating across all Australian states and territories. Against that background, however, the historic Mabo (1992) decision gave recognition to Indigenous land rights and the subsequent enactment of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth.) (NTA) ushered in an emerging and complex new aspect of property law. While receiving wide political and community support, these changes have had a significant effect on those long-established tenure systems. Further, it has only been over time, as diverse property dealings have been encountered, that the full implications of the new legislation and its operations have become clear. Regional areas are more likely to encounter native title issues than are urban environments due, in part, to the presence of large scale agricultural and pastoral tenures and of significant areas of un-alienated crown land, where native title may not have been extinguished. -

Archives of the Irish Jesuit Mission to Australia, 1865-1931

Irish Jesuit Archives 2015 © The following talk was given at 21st Australasian Irish Studies conference, Maynooth University, 20 June 2015 by Damien Burke, Assistant Archivist, Irish Jesuit Archives. The archives of the Irish Jesuit Mission to Australia, 1865-1931 One hundred and fifty years ago, two Irish Jesuits arrived in Melbourne, Australia at the invitation of James Alipius Goold, bishop of Melbourne. For the next hundred years, Irish Jesuits worked mainly as missionaries, and educators in the urban communities of eastern Australia. This article will seek to explore the work of this mission from 1865 until the creation of Australia as a Vice-Province in 1931, as told through the archival prism of the documents and photographs held at the Irish Jesuit Archives. Background to Irish Jesuit Archives In 1540, Ignatius of Loyola founded the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). Ignatius, with his secretary, Fr Juan Polanco SJ, wrote in the Jesuit Constitutions in 1558, that ‘precise instructions were given to all Jesuits on the missions to write to their superiors at home, and to those in Rome, for the dual purpose of information and inspiration.’ From this moment onwards, the Jesuits, have been acutely aware to the value of documents. ‘God has blessed the Society with an incomparable fund of documents which allow us to contemplate clearly our origins, our fundamental charism.’ Father General Pedro Arrupe SJ, 1976 A history of Irish Jesuits in Australia (1865-1931) The Irish were not the first Jesuits in Australia. Austrian Jesuits had arrived in the colony of South Australia in 1848, after their expulsion from the Austro-Hungarian Empire. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

ROYAL—All but the Crown!

The emily Dickinson inTernaTional socieTy Volume 21, Number 2 November/December 2009 “The Only News I know / Is Bulletins all Day / From Immortality.” emily dickinson in20ternation0al so9ciety general meeting EMILY DICKINSON: ROYA L — all but the Crown! Queen Without a Crown July –August , , Regina, Saskatchewan, Canada eDis 2009 annual meeTing Eleanor Heginbotham with Beefeater Guards Emily with Beefeater Guards Suzanne Juhasz, Jonnie Guerra, and Cris Miller with Beefeater Guards Cindy MacKenzie and Emily Special Tea Cake Paul Crumbley, EDIS president and Cindy MacKenzie, organizer of the 2009 Annual Meeting Georgie Strickland, former editor of the Bulletin Bill and Nancy Pridgen, EDIS members George Gleason, EDIS member and Jane Wald, executive director of the Emily Dickinson Museum Jane Eberwein, Gudrun Grabher, Vivian Pollak, Martha Ackmann and Ann Romberger at banquet Group in front of the Provincial Government House and Eleanor Heginbotham at banquet Cover Photo Courtesy of Emily Seelbinder Photos Courtesy of Eleanor Heginbotham and Georgie Strickland I n Th I s Is s u e Page 3 Page 12 Page 33 F e a T u r e s r e v I e w s 3 Queen Without a Crown: EDIS 2009 19 New Publications Annual Meeting By Barbara Kelly, Book Review Editor By Douglas Evans 24 Review of Jed Deppman, Trying to Think with Emily Dickinson 6 Playing Emily or “the welfare of my shoes” Reviewed by Marianne Noble By Barbara Dana 25 Review of Elizabeth Oakes, 9 Teaching and Learning at the The Luminescence of All Things Emily Emily Dickinson Museum Reviewed by Janet -

BA Santamaria

B. A. Santamaria: 'A True Believer'? Brian Costar and Paul Strangio* By revisiting the existing scholarship deeding with Santamaria's career and legacy, as well as his own writings, this article explores the apparent tension between the standard historical view that Santamaria attempted to impose an essentially 'alien philosophy' on the Labor Party, and the proposition articulated upon his death that he moved in a similar ideological orbit to the traditions of the Australian labour movement. It concludes that, while there were occasional points of ideological intersection between Santamaria and Australian laborism, his inability to transcend the particular religious imperatives which underpinned his thought and action rendered'him incompatible with that movement. It is equally misleading to locate him in the Catholic tradition. Instead, the key to unlocking his motives and behaviour was that he was a Catholic anti-Modernist opposed not only to materialist atheism but also to religious and political liberalism. It is in this sense that he was 'alien'both to labor ism, the majorityofthe Australian Catholic laity and much of the clergy. It is now over six years since Bartholomew Augustine 'Bob' Santamaria died on Ash Wednesday 25 February 1998—enough time to allow for measured assessments of his legacy. This article begins by examining the initial reaction to his death, especially the eagerness of many typically associated with the political Left in Australia rushing to grant Santamaria a kind of posthumous pardon. Absolving him of his political sins may have been one thing; more surprising was the readiness to ideologically embrace the late Santamaria. The suggestion came from some quarters, and received tacit acceptance in others, that he had moved in a similar ideological orbit to the traditions of the Australian labour movement Such a notion sits awkwardly with the standard historical view that Santamaria had attempted to impose an essentially 'alien philosophy* on the Labor Party, thus explaining why his impact on labour politics proved so combustible. -

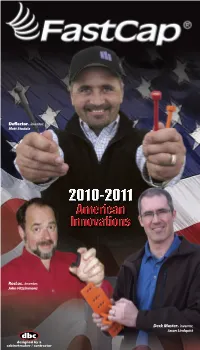

Fastcap 21-30

DeflectorTM inventor, Matt Stodola RocLocTM inventor, John Fitzsimmons Deck MasterTM inventor, Jason Lindquist dbc designed by a cabinetmaker / contractor PRO Tools VLRQDO RIHV JUDG SU H Artisan Accents TM JUHDWSULFH & Mortise Tool Turn of the century craftsmanship with the tap of a hammer. Available in three sizes: 5/16”, 3/8” and 2”, create a beautiful ebony pinned look with the Mortise ToolTM and Artisan AccentsTM. Combining the two allows you to create the look of Greene & Greene furniture in a fraction of the time. Everyone will think you spent hours using ebony pins, flush cut saws and meticulously sanding. “Stop The StruggleTM” 1. Identify where the pin needs to go and tap with the Mortise ToolTM to make the Get the “Greene & Greene” look Accent divots. 2. Install a trim screw, if using one (it is not necessary; the Accents can simply be decorative). 3. Align the Artisan AccentTM in the divots, tap with a hammer until the edge of the Artisan AccentTM is flush with the edge of the wood and you are done! Note: Apply a dab of 2P-10TM Jël under the Artisan AccentTM for a permanent hold. Fast & simple! The 2” Artisan Chisel on an air hammer leaves a perfect outline for the Accents. The Artisan Accent tools are intended for use in real wood Great for... applications. Not recommended • Furniture • Beams for use on man-made material. • Cabinets • Rafters • Trim • Decks • and more! A Pocket Chisel creates square corners for the accent 2” 5 ⁄16” A small dab of 2P-10 Jël in the corners locks the Accent in place 3 ⁄8” Patent Pending Description Part Number USD Artisan Accents (50 pc) 5/16” ARTISAN ACCENT 5/16 $5.00 Mortise Tool (5/16”) MORTISE TOOL 5/16 $20.00 Artisan Accents (50 pc) 3/8” ARTISAN ACCENT 3/8 $5.00 Mortise Tool (3/8”) MORTISE TOOL 3/8 $20.00 Inventor, Artisan Accents (10 pc) 2” ARTISAN ACCENT 2 $9.99 Jeff Marholin Artisan Chisel 2” ARTISAN CHISEL 2 $59.99 A fi nished professional look dbc designed by a cabinetmaker www.fastcap.com 21 PRO Tools TM *Four corners shown Screw the Ass. -

Weed Control Handbook for Declared Plants in South Australia

WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA A WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA JULY 2018 EDITION WEED CONTROL HANDBOOK FOR DECLARED PLANTS IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA JULY 2018 EDITION PUBLISHED BY PIRSA CONTENTS © South Australian Government 2018 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ISBN 978-0-9875872-9-9 l The following NRM Officers: ABOUT THIS BOOK .....................................................................................05 Peter Michelmore, Sandy Cummins, Kym Haebich, Paul Gillen, Russell Norman, Anton THE PLANTS INCLUDED IN THIS BOOK ...........................................06 EDITED BY Kurray, Tony Richman, Michael Williams, William Invasive Species Unit, Biosecurity SA Hannaford, Alan Robins, Rory Wiadrowski, Michaela Heinson, Iggy Honan, Tony Zwar, Greg Patrick, HERBICIDE USE .............................................................................................08 Requests and enquiries concerning Grant Roberts, Kevin Teague and Phil Elson reproduction and rights should be WEED CONTROL METHODS ...................................................................14 l John Heap and David Stephenson addressed to: of Primary Industries and Regions SA Tips for successful weed control ............................................. 14 Biosecurity SA l Ben Shepherd, formerly of Rural Solutions SA GPO Box 1671 l Julie Dean, formerly of Primary Adelaide SA 5001 Non-herbicide control methods ............................................. 15 Industries and Regions SA Email: [email protected] l The Environment -

Watching Politics the Representation of Politics in Primetime Television Drama

Nordicom Review 29 (2008) 2, pp. 309-324 Watching Politics The Representation of Politics in Primetime Television Drama AUDUN ENGELSTAD Abstract What can fictional television drama tell us about politics? Are political events foremost rela- ted to the personal crises and victories of the on-screen characters, or can the events reveal some insights about the decision-making process itself? Much of the writing on popular culture sees the representation of politics in film and television as predominately concerned with how political aspects are played out on an individual level. Yet the critical interest in the successful television series The West Wing praises how the series gives insights into a wide range of political issues, and its depiction of the daily work of the presidential staff. The present article discusses ways of representing (fictional) political events and political issues in serialized television drama, as found in The West Wing, At the King’s Table and The Crown Princess. Keywords: television drama, serial narrative, popular culture, representing politics, plot and format Introduction As is well known, watching drama – whether on TV, in the cinema or on stage – usually involves recognizing the events as they are played out and making some kind of judg- ment (aesthetically, morally, or otherwise) of the action the characters engage in. As Aristotle observed: Drama is about people performing actions. Actions put the interests and commitments of people into perspective, thus forming the basis for conflicts and choices decisive to the next course of action. This basic principle of drama was formu- lated in The Poetics, where Aristotle also made several observations about the guiding compository principles of a successful drama. -

Television Academy Awards

2020 Primetime Emmy® Awards Nominations Totals Summary 26 Nominations Watchmen 20 Nominations The Marvelous Mrs. Maisel 18 Nominations Ozark Succession 15 Nominations The Mandalorian Saturday Night Live Schitt's Creek 13 Nominations The Crown 12 Nominations Hollywood 11 Nominations Westworld 10 Nominations The Handmaid's Tale Mrs. America RuPaul's Drag Race 9 Nominations Last Week Tonight With John Oliver The Oscars 8 Nominations Insecure Killing Eve The Morning Show Stranger Things Unorthodox What We Do In The Shadows 7 Nominations Better Call Saul Queer Eye 6 Nominations Cheer Dave Chappelle: Sticks & Stones Euphoria The Good Place 07- 27- 2020 - 22:17:30 Tiger King: Murder, Mayhem And Madness The Voice 5 Nominations Apollo 11 Beastie Boys Story Big Little Lies The Daily Show With Trevor Noah Little Fires Everywhere McMillion$ The Politician Pose Star Trek: Picard This Is Us Will & Grace 4 Nominations American Horror Story: 1984 Becoming black-ish The Cave Curb Your Enthusiasm Dead To Me Devs El Camino: A Breaking Bad Movie 62nd Grammy Awards Live In Front Of A Studio Audience: "All In The Family" And "Good Times" Normal People Space Force Super Bowl LIV Halftime Show Starring Jennifer Lopez And Shakira Top Chef Unbelievable 3 Nominations American Factory A Black Lady Sketch Show Carnival Row Dancing With The Stars Drunk History #FreeRayshawn GLOW Jimmy Kimmel Live! The Kominsky Method The Last Dance The Late Show With Stephen Colbert Laurel Canyon: A Place In Time The Little Mermaid Live! Modern Family Ramy The Simpsons So You Think